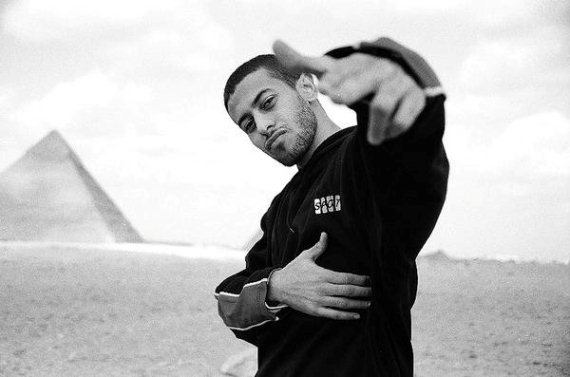

Karim Rush—a.k.a. Rus—is a rapper and co-founder of Egypt’s first widely successful hip hop act, Arabian Knightz. Banning Eyre visited him at his home in Cairo in August, 2011. Here’s their conversation.

B.E.: How did you get into rap?

Rush: It was the type of music that enabled us to talk about other topics than love songs. That’s what the pop scene here is about. Rap allowed us to express ourselves. The music we’re doing is more free. Not just love songs. You can address your actual problems. The only people outside hip hop that used to do that were Mohamed Mounir, or older songs by Abdel Halim Hafez, or Fairouz. The pop scene now doesn’t allow you to do that. Hip hop enabled us to do that without having a singing ability.

B.E.: You mentioned older music. What about Sheikh Imam?

Rush: Sheikh Imam and Ahmed Fouad Negm the poet. Sheikh Imam is a blend between Sha’bi music and hip hop music. He didn’t have the vocal ability to sing that well, but he made songs to make the statements. It’s a more melodic form of what we call hip hop. He was really street and really political.

B.E.: Prototypical hip hop. Hip hop before there was hip hop.

Rush: Yes. And the poet who wrote his stuff, Ahmed Fouad Negm. He was really a poet. I met him before. Rap is really poetry at the end of the day. If he knew about hip hop, he probably wouldn’t have worked with Sheikh Imam. He probably would’ve just got on the mic himself. So we had that culture before hip hop.

B.E.: You say you met Ahmed Fouad Negm?

Rush: Yeah, he’s still around. I met him 3 years ago. He was doing a show before us. We met him backstage. He’s quite a funny dude, but also very deep. He was a troublemaker when it comes to politics. He went to jail a lot in his time.

B.E.: He must be happy now with the revolution.

Rush: Yeah. His daughter was taking part in it as well. She’s a politician. She’s quite an activist too. She was on the news recently.

B.E.: So there are some models in the past. But the great wave of recent popular music has been about love and escape.

Rush: Exactly – “She wants me, she doesn’t.” The politicians wanted the music to stay that way. They wanted the people who were singing to stay away from politics. This wasn’t the case during the times of Sadat and Abdel Nasser, because the singers obviously were doing more political songs at that point. Abdel Halim was a very romantic singer, but at the same time, he was singing about the war. He was singing about the social issues that were going on. Politics were always a form of music in Egypt until recently. Now we’re just bringing it back. It was never away. No, no, no. It was never away. Abdel Halim died during the first two years of hip hop, if 1974 counts as the first year of hip hop. He probably gave the torch to hip hop before he died, spiritually.

B.E.: And what about the great sha’bi singer, Ahmed Adaweyya?

Rush: Adaweyya? He had more social songs, commentary songs. Comedic political songs, metaphorical songs. More hidden, not really out there.

B.E.: I’ve heard that Abdel Halim didn’t really like what Adaweyya was doing at first, but he realized that this was the way music was going. Then he started making his songs more direct, with more common, street language.

Rush: Abdel Halim went one time to one of Adaweyya’s concerts and he got onstage and sang one of Adaweyya’s songs with him. It was very smart of him. Even now, some of the fans in the older generation are not accepting of what we’re doing. But you know what? If Abdel Halim was alive, he would have accepted it. That’s why we sample Abdel Halim in one of our songs on the album, you know, because we feel like Abdel Halim passed the torch to Adaweyya and Adaweyya passed the torch to us. Generation to generation.

B.E.: That’s very interesting. So what’s the history of hip hop in Egypt?

Rush: You can’t really say it’s a long history. I started in ‘99. My influence was before. Before Egypt, I was in Oman. The hip hop scene was more available there as a market. When I came here, it was shocking: people were not very accepting of the way we dressed. I had to introduce it to them bit by bit. I had to form a group with ex-pats from 2001-2005. Then I met a group and we started to rap in Arabic, make it more reachable to the people here. We started recording with Arabian Knightz and recording online. And the internet really helped. If it wasn’t for the internet, we wouldn’t have a chance to get a deal. The fanbase on the internet really helped us.

B.E.: You say you have a CD. Do you have a record deal?

Rush: We were supposed to. The record deal didn’t go too well. They just slowed us down. We had the album finished, but we just didn’t have the distribution deal. We produced the album when we were working on the deal because they were not paying anything. We just sat on the album. We’re working on a deal with EMI or Melody. It’s already finished, already mixed and mastered. We’re just doing the artwork now.

B.E.: So this is your first album, The United States of Arabia. And you have the Youtube stuff. I’ve seen some of it, very nicely produced.

Rush: Which one did you hear? “Prisoner?” That’s a self-edited video not by me. My sister edited it while I was in Tahrir.

B.E.: This will be your first CD.

Rush: Correct. We’ve released a mixtape before. We’ve sold 1 or 2 thousand copies during our shows. We got together with Arabian Knightz and a lot of other rappers. We formed something called the Arab League Records. Compilation songs, with a rapper from each group. Egyptian rappers. 15 to 18 songs. We featured some rappers from Jordan and Palestine as well, but mostly Egyptian rappers.

B.E.: So how big is the scene now?

Rush: It’s huge. The amount of demos I get on my inbox from amateur rappers everyday is crazy. I can’t even keep up with the names anymore. It’s a lot of rappers.

B.E.: Who are the big rappers here now?

Rush: The Pharoahs. Flowkilla. Yasser. Asphalt. Y Crew in Alexandria. Toqueez. It’s a big list. MC Amin. Hossam. Mickey, who’s an actor, a very well known comedian. He raps on the soundtracks of shows and movies. The biggest names right now are Arabian Knightz and MC Amin and Hossam.

B.E.: So do these acts have records, or are they just using the internet and YouTube?

Rush: As I said, Mickey is doing soundtrack songs. He released videos at the time of his movies. They have to do with the topics of his movies. MC Amin has two mixtapes out for free downloads. He has a few videos underground. He’s about to start working on his official album.

B.E.: So this scene mostly lives on the internet. What about performances?

Rush: Because of Sawy Culture Wheel and Azhar Park and other places open to new genres of music, we have a lot of performances. We already have the fans so they’re not worried about people showing up. We set a date, we throw a party, and two- or three-thousand people show up.

B.E.: You have performed at Sawy Culture Wheel, in the Wisdom Hall?

Rush: Yes. The one right next to the Nile.

B.E.: And El Ganeina Theatre in Azhar Park?

Rush: Yes, we did 3 shows in Ganeina before. All of them were with the Spanish director Danny Panulo. He likes to incorporate B-Boys from here and Spain as well as rappers from here and from Spain. That’s the only time we do shows at Ganeina. It’s more of a Roman theatre. We don’t really do shows there unless it’s with Danny Panulo. I don’t like the concept of the fans being above and you being below. For hip hop, I feel like you should be more in control of the situation mentally.

B.E.: I could see how that wouldn’t work so well.

Rush: Yeah. That’s another one of the things that is not nice about incorporating history with hip hop.

B.E.: Wow, so it’s a big scene. I talked to some of the guys in the much smaller heavy metal scene. For them, Sawy was a breath of fresh air. There was nowhere for them to be.

Rush: In the 90s, there was a huge conflict over heavy metal. I was still fresh into hip hop. We heard all this talk of “Satanic” stuff. Of course it was media hype. I don’t know who it was. Maybe a personal issue somebody had against them. Maybe it was the media, maybe politics. I’m sure most of them were not into the Satanic thing. I was not even into hard rock and that kind of stuff. I know Bon Jovi is not Satanic. I know that Metallica is not Satanic. I’m proud of them for getting through that. They’re still persistent. I know one of the artists from back in the day. He’s still recording songs. They’re still working.

B.E.: The ones we met were really just kids. But you know, even in our country, a lot of people don’t really understand heavy metal. They get put off by the trappings. They don’t get the theatre of it.

Rush: Yeah, that’s what Kiss and them were doing with the makeup and everything. It’s the 80s era of theatrical performance. They still have these theories on YouTube. I don’t actually think Led Zeppelin recorded the song for you to play backwards. There’s a big difference between a conspiracy and a conspiracy theory. I think a lot of the people who are putting the conspiracy theories are just watering it down so you don’t know what’s the truth and what’s not.

B.E.: Have you guys and other rappers faced any obstacles? Have you faced criticism?

Rush: Criticism? Yeah. You always face criticism. You know how Arabs are. The new generation is open. The old generation is resistant to anything new. Because they are scared of anything they can’t control. If they can’t control it, they’re afraid of it. Especially the old system we had – the regime. They’re very old school, Nazi era or something—that mentally. Most of the people in government were 70-something. They still come from a time when it was okay to put cameras in everyone’s homes. When it was okay to apply your own rules no matter what people want. They didn’t even have GPS in Egypt, man. Can you believe it? It was something the government did not understand, and so they banned it. So when we came, the media was all, “These guys are Westerners. They’re trying to do Western music. They are trying to be Americanized.” They didn’t really understand the concept that rap is rhythm and poetry. Poetry was incorporated in the Middle East, and especially in Arabia, during the times of Mohamed.

That’s why they Koran came out in poetic form, because it was the miracle of the time. Moses--the fad at that time was magic so most of his miracles were more magical. Turn the stick into a snake and all that kind of stuff. Jesus came at a time when medicine was the thing. That’s why most of his powers were healing powers with more medical things so that’s why his miracles are more medical. Mohammed came at a time when literature and poetry were the fad at the time. That’s why he came with the Koran which was written in poetic form. Therefore, it’s something that’s been in our culture since 1400 years ago. You’ve heard of Gilgamesh, right? It was also written in poetry. It was written in Persia ,which is still the Middle East. So rap is from poetry and poetry is a Middle Eastern invention. So it’s not really away from our culture. They didn’t understand that until we started saying it in interviews. That’s why my generation was like, “Hey, we don’t feel guilty about listening to rap anymore. Now it’s not an American thing anymore to us. It’s something that we can relate to. If our people are doing it, speaking about our problems, it’s 100% Egyptian to us.” That’s what helped it reach people faster despite their attempts. While we were doing politics, one of our members got a number from a 000 number calling him, giving him a threat.

B.E.: 000? That’s the government?

Rush: Probably. I don’t know. It’s just an unlisted number. Hidden. Maybe the government. A threat. Someone talking in broken English, telling him that they’re watching him. That was a call he received two years ago. We didn’t water down our music obviously. If something was gonna happen, something was gonna happen. Thankfully something happened in our favor before something bad reached us and we went to the “behind the sun” scene, as they call it. That’s what it’s called when they grab you and you’re never seen anymore. It was called “behind the sun.” They take you behind the sun. Yeah.

B.E.: Did that happen to any rappers?

Rush: No, not that we heard of. In Egypt, no. It happened to El General in Tunisia, yeah. But in Egypt, you wouldn’t have come back. He’s back now; he’s working on music. But in Egypt, no. They used to send people here from Guantanamo here to get extra torture. I wouldn’t want to touch that.

B.E.: So let’s talk about what happened this year.

Rush: As I said, we had some songs previously recorded that we released during the revolution that did really well. The song called “Rebel,” where we sampled Lauren Hill was one. I felt that she was talking about Egypt when she recorded that even though she’d never been to Egypt. For some reason I didn’t release it right after I recorded it. Even [Arabian Knightz] rapper Shynx asked me, “When are you going to record it?” I said, “I’m taking my time on the mix.” Then January 25th happened and I said “I’ll mix it and I’ll wait.” I went to Tahrir myself. You know how the police attacked people at night. We all said they needed strength in numbers. The 28th they just lost control of us. It was crazy. We just felt like, “It’s now or never. We’ll either be slaves here or we’ll be free. If we die here, we die here.”

B.E.: That was when the internet got turned off, right?

Rush: That was the 28th. I wasn’t really here to know. We all came back on the 29th to join the home security system we did in our neighborhoods. They’re incorporating it for those riots in London now. That’s what I heard. That’s when we found out our internet got cut. Our songs got a lot of attention. We stayed here for 4 days or something. And then we went back to Tahrir.

B.E.: I heard that the government thought that they would break the lines of communication by that, but actually, people who had just been participating online decided then to go to Tahrir.

Rush: They were dependent upon that, and they thought that we would have to leave Tahrir to protect our own neighborhoods. We used to exchange days actually. We used to do shifts to Tahrir. It was very well organized in our neighborhood. It’s the same thing that happened in other neighborhoods. We’ve always been told that we’re a barbaric people that can’t organize anything. We have a third world government, but we’re not a third world civilization. We cleaned Tahrir; we cleaned our neighborhoods. We put trash cans all around Tahrir and the government took it out. So we knew that the people had the good in them. If we are left to control the whole country, this country will be amazing. That’s what we’re aiming for in the next elections is to pick someone who can take that spirit from Tahrir and carry it on.

B.E.: It’s really interesting that you’re working with the Sufi singer Mahmoud Al Leithy. He seems to be very important in what he represents, a religious singer making inroads in the underground pop scene.

B.E.: It’s really interesting that you’re working with the Sufi singer Mahmoud Al Leithy. He seems to be very important in what he represents, a religious singer making inroads in the underground pop scene.

Rush: Mahmoud Al Leithy is a very, very amazing artist. I actually have some footage of the recording session that happened. Believe it or not, we recorded here. We recorded the first single. It came out really nice. It was an idea: Whenever I hear the sha’bi music, especially the happy music, not the sad songs, it always sounds like the down-South crunk/reggaeton music that’s in America right now. I said “Why don’t we mix that with that and see what’s the outcome?” They have these funny keyboards in sha’bi music. I got a piece from the internet of that. I sent it to a producer from Morocco and said, “Sample this and use a down South beat for it and use these switches and let me hear it”. Then I said “Now I need a sha’bi singer.” I need a vocalist who can do a different hook on each chorus, different lyrics on each chorus. I called someone and he knew Al Leithy. He came here and recorded on the spot without even having to practice. I made him record first and then I wrote our raps. I think the song leaked already—from his side—on all the forums and the websites that have to do with sha’bi music. It’s already there. It’s getting known now. I’m really shocked because the song is not really promoted yet. I can only imagine what will happen when we shoot the video for it.

B.E.: Which song?

Rush: It’s called “Moulid.” After “Moulid” we did another song with a more down-south sha’bi singer. The song is called “Esha.” It has the drums and the instruments they play down south. So we have two sha’bi songs. One from the Cairo sha’bi style and one from Saidi, the south. The singer is L. Fashny. He’s a 100% Sufi singer but his vocal abilities let him do any form of singing. I’m sure if you get him on a rock beat he’ll kill it.

B.E.: Those Sufi singers are the most amazing that I’ve heard of young singers. This moulid we went to – the singers were amazing.

Rush: The Sufi singers are always amazing. I’m doing another project right now that’s a soundtrack for a documentary about the revolution. I’m trying to really go crazy with that one but unfortunately the time gap we were given was not good for us. I’m trying to do that for my solo album if I get the chance. I’m trying to get a rock band to play hard live music and have some places in the song where I rap. I want the whole thing to go with vocals from Sufi music. The high notes that Sufi singers hit with rock music – it would be crazy. I need to get somebody with me in the studio with the band. That’s the next project – mix even more music genres together.

B.E.: Let’s talk about the Arabian Knightz album. It has those two sha’bi songs. What else is there?

Rush: We have “Prisoner,” which we already leaked out during the revolution. He had no sense of wanting to hold onto it until the album was out. We have a song that we shot called “Sisters.” It’s apologetic and paying tribute to women worldwide which is something that needs to be done more globally. People say that the media in the Middle East are very sexist toward women. But it’s not just in the Middle East. Women are being objectified everywhere. It’s a global problem that we need to address. That’s why we need to make a video. We have Shadia Mansour, as well as Sphinx rapping on it. It’s a very mellow song. The message is very easy to capture. We have other songs as well. We have other songs on the album, like “Uknighted,” the finale of the album– it’s us with 25 rappers from the region. It’s in English as well as Arabic so it has a world message. The beat is from a producer of WuTang. Sampling one of the biggest composers in Egypt. One of his pieces he did for the 5th of October war. It’s just crazy. The intro with us introducing ourselves in the beginning over some epic sounding medieval music with me rapping over in Arabic. There’s songs about Arab unity, pan-Arabism. We have a song about corruption that we recorded about 3 1/2 years ago and kept on the album called “Medina – Tears of the City.” We have the sha’bi music. For me, that’s a music that I’m proud to be doing. It’s party music, but you can throw a message into it. That’s what sha’bi music usually is – It’s very crunk music that they do at wedding music but you can throw a message into it. The album is called “United States of Arabia.” USA

B.E.: That’s exciting. I can’t wait to hear it. Talking about sha’bi music – it’s been kind of a surprise. Ever since I’ve been here, I’ve been asking people, “Who are the new emerging artists?” All the older generation say “Oh, it’s too early to answer that. There’s all these people out there. They were in Tahrir so they’re being lifted up.” No one wants to answer that question. But when I push people to talk about what they’re excited about. This is Basma el Husseiny and Debbie Smith of El Mawred. Also the composer and bandleader Fathy Salama.

Rush: We were supposed to work with Fathy Salama a long time ago, but the communication was through Salam who was with Arabian Knightz, and he left to go solo. Fathy Salama is an amazing composer; he’s won Grammys. He worked with Youssou N’Dour, global names. At some point I want to work with Youssou N’Dour. I’ve heard his songs with Wycliff Jean. I’ve heard him work with hip hop so I know that his abilities are amazing. If I can put Yousou N’Dour and a Sha’bi singer on a song with me, it’ll be epic. His vocals, his tone are similar to the Sha’bi and Sufi singers. We can just mix him with that, and put some rap into it, it will probably leave planet Earth and go to other galaxies.

B.E.: We’ve known him for a long time since he was one of the first guys we covered. He’s very versatile. We actually saw Fathy perform with Youssou a couple years ago in Morocco.

B.E.: We’ve known him for a long time since he was one of the first guys we covered. He’s very versatile. We actually saw Fathy perform with Youssou a couple years ago in Morocco.

Rush: Exactly, he played in Morocco.

B.E.: Also Mohamed Refat, the experimental musician with the label 100Copies. He was also all telling me the most exciting music they’re hearing in Egypt is at street weddings. With their keyboards, sha’bi music with vocals. This is a whole new wave in Egyptian pop music. What do you think?

Rush: If it wasn’t true, I wouldn’t have worked with sha’bi singers as a rapper. That’s one of the first forms of music that I had to work with, because this needs to go to America, and this is not going to go to America unless it goes through a blend. I had to blend it with hip hop to introduce it to people over there. Because if you play Sha’bi music in any club in America, people would go crazy. With all respect to crunk music and to reggaeton, this is the new thing right now. This is the new crunk. They even have dances that go along with it in Egypt. I don’t know if you’ve seen that estefa dance where they grab two knives and do a weird, crazy action with it. It’s insane.

B.E.: It’s so interesting to hear that. I think you’re right, it has this special power. Who are some of the artists who are gonna be part of this new wave?

Rush: Al Leithy’s kinda new. There’s Baru who’s already big. He’s been in movies. There’s DJs who just make beats and talk over them. Kind of like how Fatman Scu does. Shoutouts to certain neighborhoods. DJ Figo. If you listen to his beats – he really listens to reggaeton and hip hop, and mixes them with the Sha’bi music. There’s already people in the sha’bi scene who are not really literate like that when it comes to music, but they know how to blend. They know how to make their own form of music. That DJ Figo guy, he’s all over the internet, and his beats are insane. Al Leithy is one of the big names. Mahmoud el Husseiny is already known. I can’t really say he’s up and coming; he’s already up.

B.E.: Al Leithy’s kind of a new discovery.

Rush: Al Leithy performs in weddings, in places that are really ghetto, like in Imbaba, in the countryside. They don’t listen to Tamer Hosni. They want to get crazy in their weddings. That’s the kind of people they bring to get crazy in their weddings. He’s also a Sufi singer. He comes from the Sufi ceremonies from the moulid where they get up and start chanting Allah – that scene. One of the most famous Koran readers and vocal reciters is one of his relatives. He comes from a very Islamic/Sufi/musical background.

B.E.: The Koran recitations are very interesting. I appreciate it more now that I’ve met so many great artists. I realized how much a high art it is. And how many singers started that way.

Rush: Of course. The Koran itself is very strong emotionally to recite. It gets you very emotional. That’s why people cry when they hear them recite the Koran – it’s very strong. With their vocals and their own melodies that they add to it. It’s out of the universe.

B.E.: The combination of the words, the perfection of the poetry, the fine pronunciation, and the makam [musical modes] on top of it…

Rush: I think the makam and the tajweed [pronunciation] of singing in Arabic comes from reciting the Koran. I think Bilal was doing it all these people. I don’t know if they were taught how to do it, or if it came naturally. If they were taught, it came from above. That did not come from earth – that way of reciting and singing, the vocals, the notes… It had to come from a divine source.

B.E.: I’m interested in what you are doing. A lot of people might imagine “Oh, hip hop, that’s new, that’s about getting rid of the past.” But you have so much of the history and the culture. It’s really about bringing it back.

Rush: It’s bringing it back really.

B.E.: Do you ever go to that venue Makan, where they present a lot of traditional music?

Rush: I think I’m going to Makan. They have connects with traditional musicians. Every city in Egypt has its own form of traditional music. There’s no such thing as traditional Egyptian music. You can’t put it into one category. There is Saidi music, Alexandria music, there is Ismailla music. Each city has its own sound, its own instruments, its own traditional music. Not having that in the media will destroy them if we don’t incorporate them. Makan is a place that I appreciate because it brings that back. Maybe a project that blends live music from this type of music with rock or rap that we do. Whatever it takes to get these people back into the media, into the mainstream.

B.E.: I’ve been to Makan a few times, and spoken with Ahmed al Maghrabi, who runs it. I think he’d be very open to it.

Rush: I met him before and he was already open minded. I just need to go back and sit down with him again.

B.E.: We also went to Port Said with Zakaria of El Tambura and heard some simsimiyya musicians.

Rush: Simsimiyya is amazing. The instrument itself. You don’t know where its from – “Is it Scottish? Is it Egyptian? Where is this from?” It’s amazing.

El Tanbura

B.E.: Those musicians are also very open to trying new things. I hope you do manage to work with those guys. There are so many good things happening with Egyptian music. But when I go and talk to these people, they’re a bit competitive. It’s hard for them to see that their part of one thing.

Rush: It’s the crab mentality – push each other down so that nobody goes up. I’m against that. That’s why I work with so many other rappers all the time. The mixtape was an embodiment of that. There was no song on the new album that was just Arabian Knightz. Each song had one or 2 members of Arabian Knightz and other rappers. The new project I’m working on, the soundtrack, is like that. It’s like a bunch of rappers, and the rock band, and a bunch of other singers from outside the rock band. We’re all together on every track. That’s very important. We need to work together rather than against each other. There’s no time for competitiveness right now. Especially in hip hop. There’s a lot of ego. You can’t let that go on now. When it’s as big as in America, then you can start the ego thing – do the Biggie vs. Tupac thing again. But here, at this stage – No. Our fans have to push us together.

B.E.: And that really is a metaphor for something much bigger. The unity. Tahrir Square was an amazing historical achievement.

Rush: Tahrir – it was a utopia. I’ve never seen that in my life nowhere on earth. Somebody comes from a mentality that he throws trash on the floor because he doesn’t think that this is not his country. He hates the government so he’s trashing his country. There if somebody threw something on the floor, he would get criticized. People would say, “Hey! This is our country! What are you doing?” Women are passing – people would make way for them. People who maybe were abusing them a month before. People were acting civilized, to the point that it was a utopia. This mentality is still with us. But the people that were demonstrating were only 12 million out of 85 million. It still has to travel more to reach the rest of us.

B.E.: I hear there are 50 or so candidates for the presidency. That’s not unity.

Rush: No, that’s not unity. That’s why I didn’t join any of the political parties, even ones who were part of the revolution. Everyone wants to be the hero, to say they were behind the revolution. We all know that nobody was behind the revolution. We just used our own minds and went out there. The post-revolutionary era is going to be difficult. The unity has to be stressed. Not just political, but personal. Like the song we shot in Tahrir. It’s about unity. It was released before the whole problem between Christians and Muslims in Imbaba, but during that problem it was playing on TV several times a day. Right now the most important issue is change and unity – they have to go together. That’s very important right now.

B.E.: Amen. I want to end by asking you about the cultural side and the musical side. This whole idea about creating a new music for new Egypt. I think a lot of those same lessons apply. You’ve had a big problem with the media. They only want to play certain kinds of music.

Rush: Yeah, music that’ll hypnotize the population basically.

B.E.: That obviously has to change. But when I talk to older musicians, they’re not too optimistic that things are going to change on the cultural side. They still feel that the powers that be still control what gets released.

Rush: That’s very breakable though.

B.E.: People like you feel more hopeful.

Rush: As long as the internet is around. The fact that the internet cannot be as powerful as it is in America is because we can’t buy anything online here. The younger generation doesn’t have credit cards. We don’t have Paypal here. Until that is solved, it will mean less sales for everyone, even pop artists. The pop stars have not sold much since the revolution. All these albums flopped after the revolution.

B.E.: And now they can’t do concerts because there’s no sponsors and trying to be careful.

Rush: We tried to organize our own concert and bring the Gorillas, Massive Attack, Erika Badu in Tahrir Square right after the revolution in March. Just bringing sponsors to fly them over to America. From people who know them, they said they’d even perform for free for the revolution. But just finding sponsors to fly them here, to get hotels—we were not able to do that. No one was willing to invest in that. That’s what’s messing with the economy. Investors are scared. Just invest. Concerts, whatever. Just let the money circulate. That’s what’s gonna help the economy. Otherwise they’re just contributing to their own downfall.

B.E.: OK, but the problems with the economy, where the government is heading, the need for Paypal. These are solvable problems, but it’s complicated. Maybe the most fundamental part of creating a new cultural scene that’s about spirit. Creating a new attitude in artists and listeners.

Rush: People think the whole scene is going to be wiped out overnight and a new group to come to replace them. That’s not going to happen. Even the president when he was wiped out, we still need two years or so to find a replacement. The older generation is still fighting to stay. They’re falling. Give them time to fall, and time for a replacement to step up. Most of the rappers, we’re still finishing our albums, we’re still finishing our deals. Sha’bi is still going to be sha’bi music for awhile, until it gets heard by more people. It’s gonna be a transition time. Even before the revolution it was already starting to happen: Who’s been requested for shows outside of Egypt? Rappers. Not pop singers. The new forms of music.

B.E.: I feel excited to see this at this moment. I can really feel like something is happening. Some of these old guys who aren’t optimistic… maybe it’s because they’re too caught up in the past.

Rush: They were saying the same thing about Mubarak’s regime. A year ago, if you said to anyone, even our generation, “Mubarak will be in bars” they would have laughed. Guess what? Mubarak is behind bars. Change happens when God wills it to happen. No matter how much we plan, no matter how optimistic or pessimistic we are, it’ll only happen if God wants it to happen. And trust me, some of that music I think God does not want it to stay for too long, because it’s just been hypnotizing the people, and it’s been putting down more important music. Because music is very important in changing the generations, by the way. If you want to reach the generation, the easiest way to reach them is not by books and not by speeches. It’s either by music or by movies. This is the fastest way to change a generation’s mind. So if there’s a positive change that’s gonna happen, music is going to be part of it. Whoever is not taking part in that will fall apart. Right now, it’s falling apart. So a lot of these pop singers are trying to use the revolution to get all patriotic and social right now. We know that they were singing about love for 20 years. Nobody’s buying their albums. Nobody is appreciating their message right now. People are just saying that they’re trying to climb the wave. Musicians like us, like rock music in Egypt, like Sha’bi music which has always been social and political, they can carry on with the social and political and they are still going to be believable. They are going to do the transition. We’re still gonna be believable. The others who are just trying to ride the transition are not going to work. Their time is gone.

B.E.: We talked to the big producer Hamid el Shari. Of course, he’s a champion of all the old pop sound.

Rush: I don’t like the way he changed music necessarily, but he did change music in the 90s. Traditional Arab music went to pop music. Regardless of whether you like the music or not, he made a change.

B.E.: He told us that the change will be in the lyrics. People are not going to sing love songs for their girlfriend or boyfriend, but sing love songs for their country. Patriotic songs, trying to ride the wave.

Rush: This is not the time for love songs for your country. We want to know WHY we were angry at the government. We want to know what our problems are. Not just that you love Egypt. We ALL love Egypt. There’s always a negative point with your lover. That negative point does not change until you point it out. That’s what we need to do.

B.E.: Hamid el Sari says he’s into change, but apparently not fast enough.

Rush: Yes. He just says “I love Egypt.” Mounir, when he did the revolution song, he criticized Egypt as the cheating lover. That’s where I’m coming from. Not just “Egypt’s amazing.” If it was amazing, we wouldn’t have revolted. Obviously there are negative points that we need to point out.

B.E.: I want to ask about the music that you heard in Tahrir. There were a lot of spontaneous singers.

Rush: Ramy Essam. I saluted him when I met him. We did a concert with him at the Tahrir Lounge. He’s an amazing guy, really down to earth. One of the smartest things he did – he took the chants that were done in the first four days to a week in Tahrir and he put it to a melody and played the guitar live and sung the chants out, and everybody sang along with him. And even the artists, nobody had no ego. We were singing along with him. We didn’t care who was in the spotlight. We were enjoying it. And it showed a real cultural side to Egyptians – even when they’re beat up, bleeding, they can pick up a guitar and start singing about it. SINGS

B.E.: That’s nice. We met him in Tahrir. He sang that song for us. It was cool.

Rush: Yeah, he’s crazy. We might work with him soon. He’s also an old friend from before the revolution of MC Amin, who was in the Arab League with us. We performed before him on a performance. After we were done, he called AmIn back on stage. They know each other from way back in the day. He’s from Ansora, which is a country city. Ramy Essam will do very well in Egypt. It’s all political. He doesn’t do any other kind of music

Ramy Essan

B.E.: I gather that his lyrics are very funny. When he played in London, the English speakers were complaining because all the Arabic speakers were laughing their heads off and they couldn’t understand.

Rush: He was in London?

B.E.: Yeah, they did a show with Ramy Essam, El Tambura, the blind oud player from Tahrir. And Azza Balba.

Rush: Azza Balba. She’s an OG as we say in hip hop. I wonder who got them? I want to go to London!

B.E.: It was at the Barbican Center. Coming back to what regular people were singing in Tahrir – If you were to sort of list the composers or singers whose songs people sang, who would you list?

Rush: Mounir. Amr Hayrat. Amr Sharai. He went of TV and spoke in favor of the revolution; he was really happy about it when most of the media were talking against it. He was brave enough to not do that. And there were singers – Mounir, Hagar, Sheikh Imam, The poet Ahmed Fouad Negm. Nebuk Shalayahim. He’s one of the most political poets during the Nasser era, 60s, 70s. The funny thing – there was a compilation of his poetry and the publisher was Suzanne Mubarak. She didn’t know what she was doing I guess. Big mistake, Suzanne.

B.E.: I heard that some of these DJ guys from weddings were also popular in Tahrir. Is that true? Actually coming and performing.

Rush: Well maybe their songs were playing on Ipods. I haven’t seen any DJs to be honest with you. I doubt Figo and them would be there. Maybe the singers but not the DJs. I’ve seen Ramy perform on almost a daily basis. We didn’t want to go onstage and perform because we were too busy making our statement. We don’t want to hear people say that we’re trying to climb over the wave of the revolution. Although some media were actually calling it the hip hop revolution. Actually it was the generation of hip hop that came out and demonstrated. We were too occupied with demonstrating to go onstage. Ramy, he’s just playing the guitar and singing. His rhythm is not fast. It was easier for them to digest him in Tahrir as opposed to us. Even though we didn’t play in Tahrir our songs made it there through the internet. That showed the strength from hip hop.

B.E.: And the revolution is not over.

Rush: No, far from over. We haven’t done anything yet. The real start was Feb. 11. That’s when the real work starts.