In 2016, Afropop Worldwide spoke with a young Kenyan percussionist, Kasiva Mutua, when she was a member of the Nile Project. The Nile Project actually kicked off three years earlier, and as Nile Project co-founder and CEO, Mina Girgis explained to Afropop producers Banning Eyre and Ian Coss at the time:

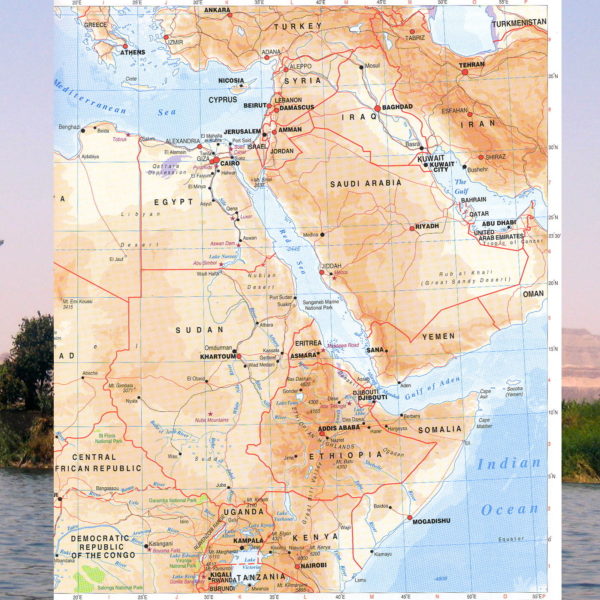

“The Nile Project is an initiative we started about three and a half years ago to bring musicians from the 11 Nile Basin countries to collaborate on music that merges many of their traditions and styles and instruments. So we have musicians from Uganda, Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, and Ethiopia, from Sudan, and from Egypt. And we are using this music to inspire a larger conversation about water and about all the challenges we face in the Nile Basin.”

We urge you to click on this article, scroll down about halfway to the interview with Mutua to get a deeper understanding of her background before finding out what's happened in 10 years since that earlier interview.

By way of a quick introduction here, Mutua began learning traditional drumming from her grandmother as a child. But part of that tradition was that such drumming was strictly the domain of men. Therefore, she faced unnecessary discrimination and harassment on her journey to realize her goal of becoming a professional percussionist. Her persistence, however, paid off and for a decade-plus, she has been involved in many endeavors, including the Nile Project, but she has also had other opportunities, including playing with Zimbabwean legend Oliver Mtukudzi, becoming a TED fellow, and being included in OkayAfrica's list of “100 Impactful African Women.”

She dropped her first solo EP, Ngewa, in 2022, and her first full-length album, Desturi, in February of this year. It is described as a “a celebration of African heritage and resilience.” We were very excited to see her showcase at the Jazzahead conference last month where Mutua delivered a kinetic performance bouncing from one end of the stage to the other, switching from guitar to percussion and back to guitar again. We were fortunate to get her to sit still for this interview the following day. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Ron Deutsch: I guess the first thing I wanted to talk about was the concert last night. I thought you were a percussionist, but you mostly played the guitar and barely the drums.

Kasiva Mutua: Did I? Out of 45 minutes, I played like 20 minutes of drums. [LAUGHING] But okay, it is true. I played guitar most of the time.

So what's that about?

So the album I recorded, Desturi, I produced it as well. And producing it made me see the skeleton of the music. So everything started from there. And it's one of those albums where I am “the dog walking myself,” because I really wanted to tell my story exactly how I've always wanted to. And for that I had to learn production, I had to learn guitar – which I picked up during the pandemic.

Now while the melodies in the music are very simple, the rhythm is super complex. It's like very advanced rhythm from all the years of playing percussion. But then what's really interesting and what I came to find out over time – even as I was recording the project – was that the way I pick guitar, nobody can pick like me. I've tried to teach it to professional guitarists and they can't do it, because I pick like I play percussion. And so the guitar is part of the percussion instruments, and in fact, the whole sound is carried by the percussion inside the guitar. So then, for that sound to sound like it did last night, for me to bring out that “Kasiva sound,” I have to play guitar myself until I can teach somebody to pick exactly as I do. Because the percussion is layered, and the most important layer that defines all the music is inside those very simple melodies. It's the guitar picking where it all is. So for me to feel at home and comfortable, that guitar must sound exactly as it sounded yesterday. So that's why mostly you saw me play guitar. But in a real sense, I am still playing percussion.

And you taught yourself this style of playing which you invented because you were in isolation?

No, not really. I mean, I picked up the guitar because I knew I wanted to put out a project. I was trying to express myself in a melodic way, because I've always expressed myself physically. And when I picked up the guitar and learned my first three chords – what I did with those chords? Lord Jesus! Like, the second song in the concert yesterday, was just two chords. And in the way that I pick, it's not something that I would say that I taught myself. It just something that came very naturally.

So when you picked up the guitar, it was just “this is how I'm playing it.”

Yeah, and I thought: this is really interesting. And then I realized it was a unique thing that was happening. Because I thought they all play like this. And when I tried to show someone this to record for me professionally in a studio as I was still just figuring out how to play, we ended up with no recording. Because I was like, “No not like that, like this. No, like this.” And the guitarist was very frustrated. He was like, “Kasiva, you have to learn to play the guitar, because you pick in a very unique way. You will need to record it yourself, because you will not be satisfied with anybody's recording. What you hear, you hear percussion. You're not hearing melodies.” And that's how it happened.

I also wanted to make a kind of music that was something very relatable to other Africans, but in the simplest way possible. Africans are naturally born with rhythm within them and the complexities of our traditions and growing up in these cultures exposes you to traditional music at a very early age, so you're able to process it all. And so when you grow up in these cultures, you're naturally prepared for complexity in rhythms. But when melodies are transferred from traditional instruments to guitar, then the simpler the melody, the better and the more digestible and palatable they are for people. So I set out to make music that's very simple, but complex in the rhythm, because that's what we naturally gravitate to.

And, well, you know, you can't put an album out by yourself. There are more than 30 people involved in this tour. So as much as I say “I,” I am representing them. There is the band, there's my co-producer Herman – who is such a young guy – and I feel like it's so important to talk about this guy. Because I first worked with Herman on the Ngewa EP, and we were experimenting together. And it was his first time working with a percussionist. Herman is a young producer of the modern age and he was used to working with beats and so now he is with a real percussionist, playing traditional instruments and he was very excited to learn.

But the good thing about this guy is he's very open-minded. Because, for example, in my poly-rhythm way of thinking – he's not been exposed to that. He's like a 4/4 guy, and here I am bringing him 4/4 in 6/8 feel. And he's like “What the hell is that?” And I take him through and explain everything, going back to poly-rhythms. And this reminded me of back in the day when we would sit with the elders, and skill is passed down by mentorship and sitting with the elders. And this was me for five years sitting with Herman, teaching him how these things go, and making him understand why the shaker is the star of the show here, and not the drum. Or why the krakeb [metal castanet] is the star of the show in this song. So I'm helping him understand the names of these things and where they're from, these cultures, where they stem from. And because he was super interested, he really got into it.

And the way we worked together was so seamless and so beautiful. He had a way of complementing my traditional way of thinking in terms of music. And Desturi sounds the way it sounds because here is somebody who is approaching music from a very traditional perspective, that is me, and there is another producer who is in the modern era, and he would just compliment everything and just give it such a nice modern touch that does not dissolve the tradition, and the coarse feeling of the music. It just complements it. It's like we have a cake, but it's just nicer with whipped cream.

Previously to the album, you had released an EP. Was that also through this process, or would the guitar thing come later for the album?

The guitar came for the new album, Desturi. The EP that I put out during the pandemic was called Ngewa, which means “stories.” It's a 15-minute EP of just percussion. And I'll be honest and tell you that I made Ngewa for myself. Because it was, for me, the learning process of understanding how music comes out from your hand to Spotify. Nobody taught me the process. And so I decided to do it like a practical experiment and say, “Okay, I'm going to put out a body of work – 15 minutes only – just as an experiment to see how it works. Because I knew I wanted to put out Desturi and I wanted to know exactly how Desturi is going to go, because I was not gonna gamble with it. Desturi is my life.

I read how you brought in some maloya rhythms from La Reunion into the album, but were there any other non-Kenyan beats you brought in. Was this sort of a pan-African thing you've consciously put into the album?

Desturi is a very intricately planned out album. It brings together multiple African cultures in one 45 minute lesson. And it was very intentional. It was research carried out for almost ten years, and then the recording process was five years.

But to be clear, I wasn't thinking about the album 10 years ago. What I was thinking about was that I've always been very interested in the time signature 6/8. I always say that my heart beats in 6/8. When I hear 6/8 on the street, I start moving my body on the street – and not being shy, because it's just my natural response. And so I was very curious whenever I spotted 6/8 and my body starts moving. I started thinking what is the relatability of that 6/8 to the 6/8 in Kenya, and so I just got into a rat hole, a very nerdy rat hole of thinking about 6/8 in Africa. And I started thinking of where they meet. What connects these 6/8's together? Because Africa is interconnected in very many ways, and I thought there must be a connecting point to these times signatures. So all these years, I was enjoying 6/8's from different places on the continent, and textures, and understanding what fits where. And then I finally found a sweet spot. And it was like an Albert Einstein moment when I was like, “Yeah, here it is !”

What is it?

[LAUGHING] That's my little secret. And when I found it, I started recording. And also, subconsciously, I was collecting small percussive instruments as I traveled. I got something from Morocco, got something from Egypt, got something from La Reunion. And now I had the original sounds that they use in their music, and now it was to cook a sound that feels Kenyan, but also feels

Zimbabwean, but also feels Malian. And it was to find the sweet spot that represents everybody by feeling – not by rhythm.

Because 6/8 creates, as I said, a feeling that wants to make my body move. So for me it was a matter of creating a feeling that relates to home. And so when I say it was very intricately planned, this is an album that was made instinctively out of feeling. Like if we were in studio and I heard a beat and it made me feel “no,” I would call it out immediately. I was very strict with being very aware how everything made me feel during the process. So it was, “I don't like the texture of this. No, let's change the texture of this shaker. It doesn't make me feel at home.” And so the culmination of all these cultures from different parts of the continent were put together. And then, with a touch of modern production from Herman, bore a sound that people say is timeless, but also people say sounds like hope – but this is different people from different regions. It’s just that it sounds familiar. And so the feeling has been attained, because I was trying to create familiarity by interconnecting cultures across borders. Even sometimes using the textures inside somebody else's rhythms, because the texture gives you a feeling of home. You hear it and you feel “I know this music.” But it's not culturally ingrained in your rhythms or your melodies, but the texture brings you closer to home.

You also have a history teaching young people percussion?

Yes, yes. So I co-founded an all-female culture collective called MotraMusic. It's a space where young women and girls come and learn rhythm and culture and understand how the music industry works. Motra was just supposed to be just that, but over time, it formed a sisterhood that's super close. It is a sisterhood that I am in now, and I call these women and we talk about random stuff, you know? Like, “I went to a gig yesterday and I have these very serious blisters.” Stuff I wouldn't tell my male counterparts because they would laugh or just say some very hurtful stuff. There's a way women just process their own emotions in their own little spaces. And it sent me back thinking that traditionally women had their own spaces to just exist in – and people can fight me – but in the modern era, the rise of feminism and equality has taken away those spaces. I see these female spaces as very important for connection and bonding and passing down knowledge and mentorship as women, because there were spaces that existed just for women to teach each other “women things” and we don't have that anymore. It's a conundrum.

And now you're out touring this album.

Yes, now this is the main focus. And I'm still recording more music because that's what you do. When I was writing Desturi, I wrote about 30 tracks. Man, I tell you, the pandemic did me a good one, I swear. It gave me time to breathe, but also time to write. So now we have a pool of music that we're gonna tour.

Well, good luck and thank you.

Thank you. That was a good conversation.

Related Audio Programs