In 1978, Bernard Treton went to Kinshasa to record bands that were on nobody’s radar. The four so-called “tradi-modern” groups he documented played music with little or no connection to the rumba and soukous that was emanating from this Congo River city like some hypnotic force field, animating dance floors from Nairobi to Dakar, Paris and New York. There was no doubt that Congolese pop had become an unprecedented phenomenon in African music, clearly the dominant dance genre throughout the continent and the diaspora. Polished, stylish, fashion-savvy and graced with intricately coordinated guitar and brass parts and elaborate, spot-on vocal arranging, this was music that transcended ethnicity and could be embraced broadly as the sound of a new and emerging cosmopolitan Africa.

The groups Treton recorded could not have been more different, except in their passion, precision and musical excellence—qualities that seem to run in the blood of Congolese musicians of all times and places. In every other way, this was local music, made by and for ethnic communities in Kinshasa.

Looking back 51 years later, the best known of these tradi-modern groups is Konono No. 1, a funeral band from the Bazombo ethnic group that played likembé (something like mbira) through massive amplifiers, creating a thrilling, distorted bed of rhythmic melody over which near-shouted (and also distorted) vocals provided comforting ambience for whole neighborhoods of small-town folk landed in the big city, usually as they mourned a recent death. To Treton, and later Vincent Kenis from the excellent Crammed Discs label, the music spoke in quite a different way. This was African garage rock, trance music par excellence. Konono would go on to become the flagship act for Crammed Discs' influential Congotronics series.

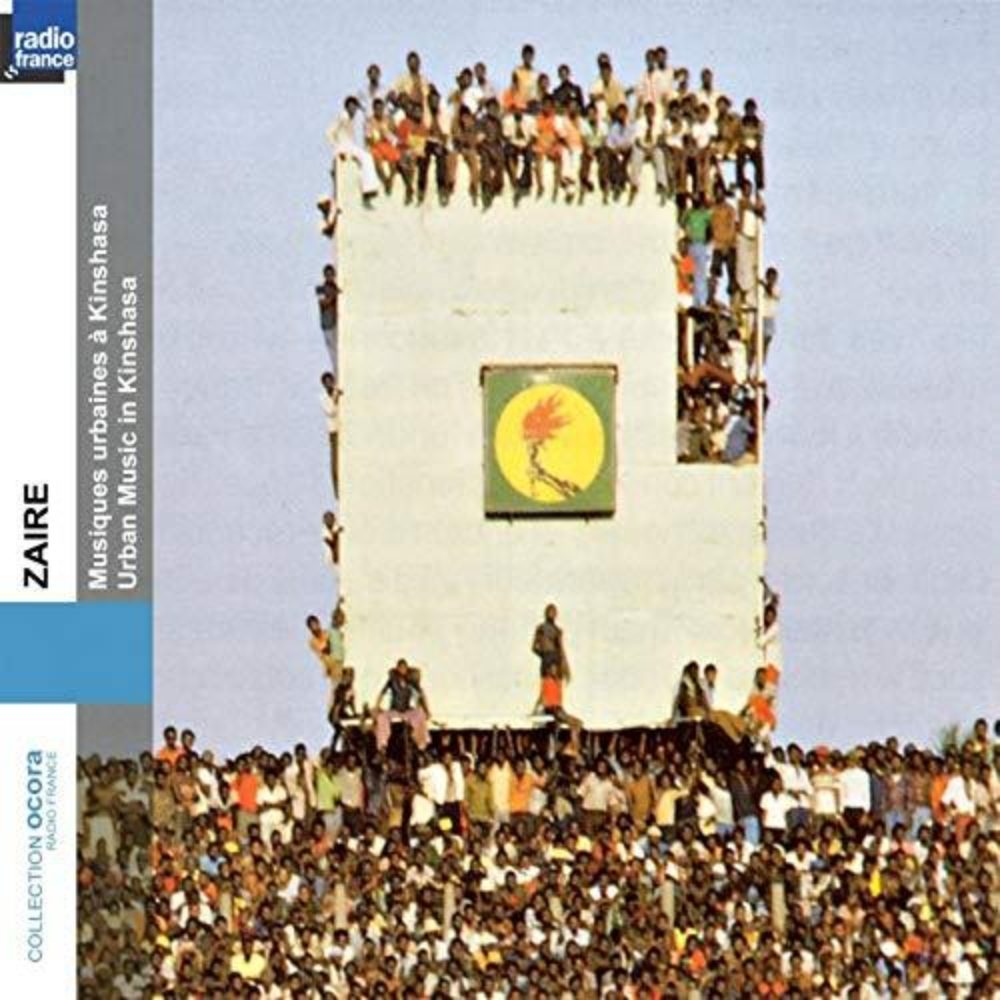

But long before that, Treton’s recordings—also of Orchestre Bambala, Orchestre Bana Luya and Sankayi—found their way to a 1986 release on the folkloric Ocora label. The title was Zaire: Musiques Urbaines à Kinshasa. These raucous, raw, joyful sounds caught the ear of folks like Sean Barlow and myself, keen to experience every new urban sound from Africa we could find. But to say that this music was obcure in the year that Graceland transfixed the world is an understatement.

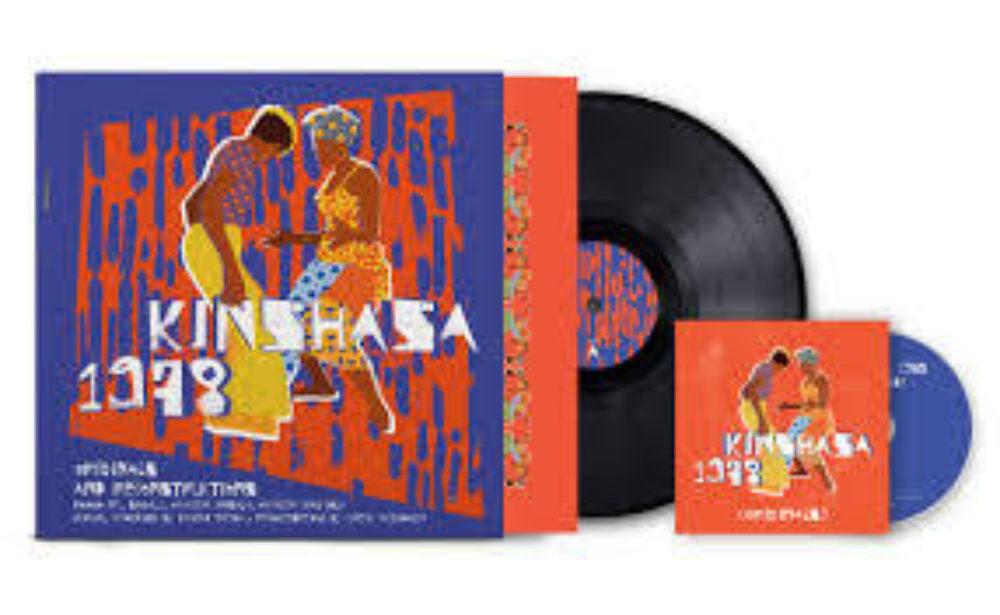

Now Crammed Discs has released a double CD package of Treton’s work, entitled Kinshasa 1978, including material not found on the Ocora release, and an accompanying vinyl disc with excerpts from the originals “reconstructed” by Martin Meissonnier . Meissonnier is a distinguished veteran of African music production, having worked with Fela Kuti, King Sunny Ade, Khaled, Haruomi Hasono and many others. A “reconstruction” is not a remix. With a two-track stereo recording, there’s not much to remix, but you can add effects, other instruments and especially, club-friendly beats that bring the ambience of the Congolese interior to the dance floor. Some may find this a dubious exercise, but rest assured Meissonnier is the man for the job, and his feel for the source material is evident on the four pieces he creates for this project.

I won’t provide ethnographic profiles of the original groups, mainly because I cannot lay my hands on the original CD with its detailed sleeve notes [It’s here somewhere…], but also because ethnography is not the point. While in no way dismissing or undervaluing the cultural and personal stories behind these spellbinding performances, the appeal of this music lies in its sound more than its story.

In Meissonnier ’s hands Konono gets a short remake with a roaring, wailing electric guitar that repeats throughout, and a fierce club beat. The familiar Konono sound is barely recognizable until nearly halfway through the track, which, at just over six minutes, is the shortest of the Meissonnier set. Shouted voices become animal sounds crying from the interior of some magic jungle. The club beat—de rigueur, I know—leaves me a bit cold. But what a soundscape!

The group Sankayi features a clean-toned likembé, fragile and resonant compared with Konono’s, and grounded by low-pitched buzzing drums and a persistent bell pattern. The chanted vocals feel like an invocation. It sounds like there is a struck wooden xylophone in there as well, sharp and dry. There are pleasing ebbs and flows over the course of a nearly 23-minute jam. The reconstructed Sankayi piece, “Il Ne Faut Pas Intervenir (Martin Meissonnier reconstruction),” also gets a groovy club beat, giving the track added momentum and heft. The forest harmony vocal cries are thicker and rowdier, and instruments, including a buzzy, loping bass line, really kick. Even this techno-skeptic would dance to this in a club.

Orchestre Bana Luya’s performance is possibly my favorite, a percolating stew of percussion, xylophones, likembé and a very active flute, with no vocals at all--delightful and hypnotic. Meissonnier adds bass and a fat bass drum beat, and vocals. He clearly enjoyed this one in particular as his reconstruction is actually longer than the original, which is already over 15 minutes.

The distinguishing feature of the fourth group, Orchestre Bambala, is accordion. The shuffling, cycling melodies it plays against staccato percussion and harmonized vocals bring to mind both Christian church music and the accordion-driven spirit possession music of eastern Madagascar—quite a feat! Meissonnier’s “Animation Kifuti” pumps up a different Bambala performance with a more strident harmony, and chant vocals not unlike the animations heard in mainstream Congolese pop. With a little bass and a steady beat and a second accordion, it’s a party you won’t want to miss.

As I contemplate this music from a half-century ago, it is the end of Afropop’s 31st year on the public airwaves, and the end of the second decade of the 21st century. The world seems as fragile and contentious as at any time since the late ‘60s. A rising generation of Africans seems poised to write a new history for the continent, though the obstacles they face—environmental, economic and political—seem daunting indeed. The split screen contrast of confident and fashionable musicians, actors and activists next to narratives of climate- and religion-driven conflicts that seem unresolvable, and ongoing scheming by foreign powers (China and France come to mind) can leave one’s head spinning.

Fed in part by the spectacular achievements of diaspora musicians in Europe and America, today’s generation of African artists is achieving successes their forebearers could hardly have imagined. They are reaching far into the global mainstream, including the world of black hip-hop and its variants, something the previous generation aspired to but rarely managed. Georges Collinet and I talk about these developments in the current Afropop Worldwide program, "Here Comes 2020." I think we both feel that it’s rather dizzying to contemplate the changes we’ve seen over the decades as African music rockets into the 21st century. With all that, I find it both grounding and oddly comforting to revisit these unvarnished rural-meets-urban sounds, from the early days of forest culture’s encounter with modernity.

By the way, for those who listened to George’s and my on-air conversation, and heard the vocal performance by 8-month-old Afropup Georgia, here’s a picture. Happy holidays!

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles