Blog April 29, 2014

Kokanko Sata Doumba: A Queen of Wassoulou Music Visits the American South

Kokanko Sata Doumbia is a composer, singer and songwriter from the Wassoulou region of southern Mali. She is one of few—if there are any others at all—women to play the kamele ngoni harp, a staple of Wassoulou music. Kokanko is now finishing up a visit to the United States organized by the Cradle of Jazz Project. In North and South Carolina, Georgia and New Orleans, Kokanko is giving concerts and workshops and participating in symposia and musical encounters. She has jammed with Bela Fleck and Abigail Washburn and on April 29 she’ll take the stage with Toubab Krewe. But Kokanko’s tour of the southern U.S. actually began in March in New York, where she stopped in at Afropop’s Brooklyn studio for a conversation and an informal performance.

Kokanko, born Sata, was born in 1968 in a village called Siekrolen in Mali, Wassoulou region. Her father was a blacksmith (as the name Doumbia indicates) and her mother was a jeli, a griot, charged by birthright with knowing history and keeping its memory alive in song. Kokanko inherited the jeli’s art, but tends to present herself in a different way, as a Wassoulou artist—like Oumou Sangare, Sali Sidibe or Nahawa Doumbia. Wassoulou singers typically proclaim that, for them, music was a choice, not a heritage. For Kokano, it seems, it is both.

Kokanko’s life in music began at age 10, when she began performing at local weddings. “I was playing calabash,” she recalled. “I would play when the bride was coming into her husband's house. When she arrives, some men would be playing djembe, and I would be singing and playing calabash. This is how I first came into music.”

[caption id="attachment_18121" align="alignleft" width="227"]

Kokanko, born Sata, was born in 1968 in a village called Siekrolen in Mali, Wassoulou region. Her father was a blacksmith (as the name Doumbia indicates) and her mother was a jeli, a griot, charged by birthright with knowing history and keeping its memory alive in song. Kokanko inherited the jeli’s art, but tends to present herself in a different way, as a Wassoulou artist—like Oumou Sangare, Sali Sidibe or Nahawa Doumbia. Wassoulou singers typically proclaim that, for them, music was a choice, not a heritage. For Kokano, it seems, it is both.

Kokanko’s life in music began at age 10, when she began performing at local weddings. “I was playing calabash,” she recalled. “I would play when the bride was coming into her husband's house. When she arrives, some men would be playing djembe, and I would be singing and playing calabash. This is how I first came into music.”

[caption id="attachment_18121" align="alignleft" width="227"] Kokanko Sata Doumbia playing her kamele ngoni in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

A few years later, Kokanko picked up the kamele ngoni. She notes that, although it is rare, women are certainly permitted to play this instrument. The kamele ngoni has its roots in the much older donson ngoni, or hunter’s harp, a sacred instrument veiled in ritual of protocol. “When one of the hunters dies,” Kokanko explained, “they organize an event and they play the donson ngoni. But this is only for old men, not for kids. So the young men, if they wanted to play that, they had to create another name: kamele ngoni. Kamele means ‘youth’ in Bambara.” This instrument is smaller and higher-pitched, and these days, players have added to its original six strings. But its most important feature was that anyone could play it—young and old, men and women. “So I tried,” said Kokanko, casually, “and everyone appreciated that. Soon they were organizing concerts, weddings, and now I'm playing the kamele ngoni.”

It’s worth noting that when Kokanko was born in 1968, the kamele ngoni had only recently been invented, and one of the musicians responsible for its creation—Satigui Dedjan—played at her naming ceremony. At an early age, Sata took the name Kokanko, referring to a small bird that sits at the edge of a village and warns travelers of impending dangers. Singers from Wassoulou are often referred to as songbirds, in part for their melodious voices, but also for this ability to deliver important messages.

Wassoulou music differs from the griot tradition in that artists tend to compose their own songs, rather than adapting them from a shared repertoire. Kokanko said she writes all of her songs, and they deal with social themes—trust, unity, betrayal. Although she was straight from the airport when we met, Kokanko sang three short songs for us in the Afropop studio. Here’s a video of the three:

Kokanko came to international attention thanks to a maverick British rocker, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), who included her in his experimental 2000 release Mali Music (Honest Jon's Records). Albarn recalled her, “singing and playing her ngoni on a boat on the Niger River in 2000—a beautiful and timeless moment.” In 2002, Kokanko became a member of Albarn’s Mali Music band, completing a European tour. In 2005, Honest Jon's released the CD Kokanko Sata that year, featuring Kokanko backed by a strong Malian ensemble. Kokanko’s only other appearance in the United States took place with a large ensemble Albarn assembled for a special Honest Jon's concert at Lincoln Center in 2008.

“Going abroad,” Kokanko said, “I learned a lot of things. I met people and learned from other experiences. I was very excited leaving Mali for another country. Staying at home, you add nothing to your experience, nothing to your knowledge. It's just what you have.”

[caption id="attachment_18115" align="aligncenter" width="595"]

Kokanko Sata Doumbia playing her kamele ngoni in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

A few years later, Kokanko picked up the kamele ngoni. She notes that, although it is rare, women are certainly permitted to play this instrument. The kamele ngoni has its roots in the much older donson ngoni, or hunter’s harp, a sacred instrument veiled in ritual of protocol. “When one of the hunters dies,” Kokanko explained, “they organize an event and they play the donson ngoni. But this is only for old men, not for kids. So the young men, if they wanted to play that, they had to create another name: kamele ngoni. Kamele means ‘youth’ in Bambara.” This instrument is smaller and higher-pitched, and these days, players have added to its original six strings. But its most important feature was that anyone could play it—young and old, men and women. “So I tried,” said Kokanko, casually, “and everyone appreciated that. Soon they were organizing concerts, weddings, and now I'm playing the kamele ngoni.”

It’s worth noting that when Kokanko was born in 1968, the kamele ngoni had only recently been invented, and one of the musicians responsible for its creation—Satigui Dedjan—played at her naming ceremony. At an early age, Sata took the name Kokanko, referring to a small bird that sits at the edge of a village and warns travelers of impending dangers. Singers from Wassoulou are often referred to as songbirds, in part for their melodious voices, but also for this ability to deliver important messages.

Wassoulou music differs from the griot tradition in that artists tend to compose their own songs, rather than adapting them from a shared repertoire. Kokanko said she writes all of her songs, and they deal with social themes—trust, unity, betrayal. Although she was straight from the airport when we met, Kokanko sang three short songs for us in the Afropop studio. Here’s a video of the three:

Kokanko came to international attention thanks to a maverick British rocker, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), who included her in his experimental 2000 release Mali Music (Honest Jon's Records). Albarn recalled her, “singing and playing her ngoni on a boat on the Niger River in 2000—a beautiful and timeless moment.” In 2002, Kokanko became a member of Albarn’s Mali Music band, completing a European tour. In 2005, Honest Jon's released the CD Kokanko Sata that year, featuring Kokanko backed by a strong Malian ensemble. Kokanko’s only other appearance in the United States took place with a large ensemble Albarn assembled for a special Honest Jon's concert at Lincoln Center in 2008.

“Going abroad,” Kokanko said, “I learned a lot of things. I met people and learned from other experiences. I was very excited leaving Mali for another country. Staying at home, you add nothing to your experience, nothing to your knowledge. It's just what you have.”

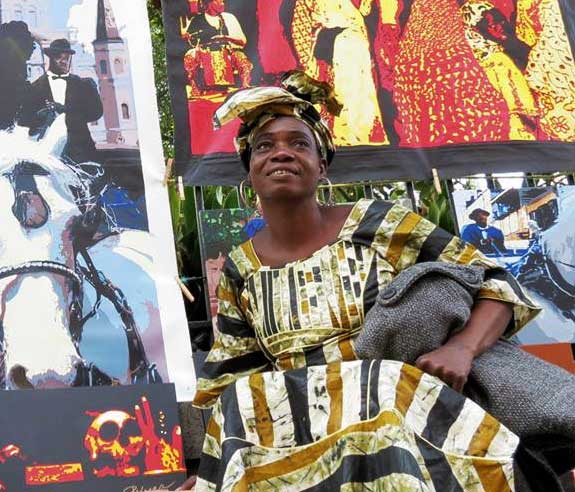

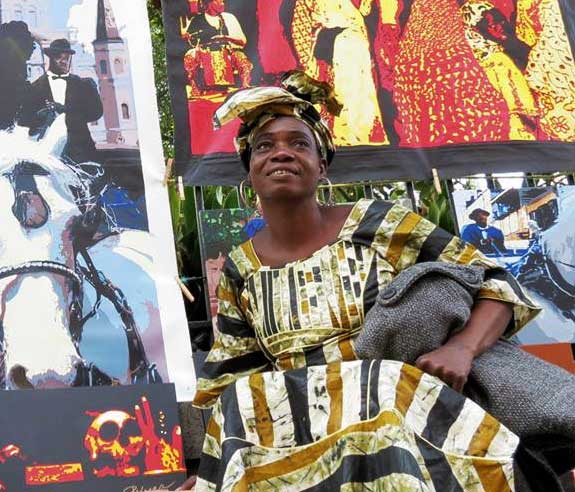

[caption id="attachment_18115" align="aligncenter" width="595"] Kokanko Sata in Congo Square, New Orleans[/caption]

After her visit with Afropop, Kokanko headed south for appearances at the College of Charleston, the University of Georgia, and Furman and Duke Universities. This tour was organized by Julie Moore, the executive director of the Cradle of Jazz Project, and an adjunct professor of music at Furman. Moore has studied West African music and dance for 15 years, and in 2010 began uncovering new evidence that the Mande played a critical role in the formation of the cornerstone of black New Orleans culture during the 1700s.

Moore has been thrilled with the tour and Kokanko’s reception. Kokanko jammed with banjo maestro Bela Fleck and his wife Abigail Washburn. Said Moore, “She and Bela totally grooved, and she and Abigail did this amazing piece where Abigail was singing an old Appalachian song opposite Kokanko singing a Wasulu song. What I've particularly appreciated about the tour is her ability to connect in a meaningful way with people—letting her ‘songbird’ role be understood with her translator (Assigué Dolo) interpreting her songs on stage.” Kokanko has made for an electrifying presence in the classroom as well. Here she is, channeling her jeli roots, with an excerpt for the praise song “Fakoly,” in a University of Georgia classroom.

Kokanko told Afropop she very much related to the idea of connecting with related music in America—the core of the Cradle of Jazz concept. “Music is knowledge,” said Kokanko. “Think about dyeing cloth. This cloth is red. But if you add another color similar to that, another similar to that, it will still be the same color. So having a connection to jazz, well, it's another person who knows jazz very well. But I can add my music to that jazz, they can fit nicely. Maybe the other one will learn what I am doing, and I will also learn from the jazz player.”

[caption id="attachment_18116" align="aligncenter" width="601"]

Kokanko Sata in Congo Square, New Orleans[/caption]

After her visit with Afropop, Kokanko headed south for appearances at the College of Charleston, the University of Georgia, and Furman and Duke Universities. This tour was organized by Julie Moore, the executive director of the Cradle of Jazz Project, and an adjunct professor of music at Furman. Moore has studied West African music and dance for 15 years, and in 2010 began uncovering new evidence that the Mande played a critical role in the formation of the cornerstone of black New Orleans culture during the 1700s.

Moore has been thrilled with the tour and Kokanko’s reception. Kokanko jammed with banjo maestro Bela Fleck and his wife Abigail Washburn. Said Moore, “She and Bela totally grooved, and she and Abigail did this amazing piece where Abigail was singing an old Appalachian song opposite Kokanko singing a Wasulu song. What I've particularly appreciated about the tour is her ability to connect in a meaningful way with people—letting her ‘songbird’ role be understood with her translator (Assigué Dolo) interpreting her songs on stage.” Kokanko has made for an electrifying presence in the classroom as well. Here she is, channeling her jeli roots, with an excerpt for the praise song “Fakoly,” in a University of Georgia classroom.

Kokanko told Afropop she very much related to the idea of connecting with related music in America—the core of the Cradle of Jazz concept. “Music is knowledge,” said Kokanko. “Think about dyeing cloth. This cloth is red. But if you add another color similar to that, another similar to that, it will still be the same color. So having a connection to jazz, well, it's another person who knows jazz very well. But I can add my music to that jazz, they can fit nicely. Maybe the other one will learn what I am doing, and I will also learn from the jazz player.”

[caption id="attachment_18116" align="aligncenter" width="601"] Abigail Washburn, Bela Fleck, Kokanko Sata, Assigue Dolo[/caption]

Apart from the richness of the sessions and musical exchanges, the tour has also provided Kokanko with a welcome break from life in Mali at a difficult time. “Even before the coup (2012), before the crisis, musicians were having problems in Mali,” said Kokanko. “As soon as they created the memory card, people stopped buying CDs and cassettes. And we were not doing that many concerts. But during the coup, and afterwards, we couldn't organize any concerts at all. Absolutely nothing of our business was working. So me, I tried to create another job, dyeing fabrics to sell in Wassoulou in the villages. I have two kids, and in order to cover the expenses of these kids, I had to do this. Really, the artists were suffering. We are still suffering.”

[caption id="attachment_18123" align="aligncenter" width="575"]

Abigail Washburn, Bela Fleck, Kokanko Sata, Assigue Dolo[/caption]

Apart from the richness of the sessions and musical exchanges, the tour has also provided Kokanko with a welcome break from life in Mali at a difficult time. “Even before the coup (2012), before the crisis, musicians were having problems in Mali,” said Kokanko. “As soon as they created the memory card, people stopped buying CDs and cassettes. And we were not doing that many concerts. But during the coup, and afterwards, we couldn't organize any concerts at all. Absolutely nothing of our business was working. So me, I tried to create another job, dyeing fabrics to sell in Wassoulou in the villages. I have two kids, and in order to cover the expenses of these kids, I had to do this. Really, the artists were suffering. We are still suffering.”

[caption id="attachment_18123" align="aligncenter" width="575"] Kokanko Sata in New Orleans[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_18118" align="aligncenter" width="450"]

Kokanko Sata in New Orleans[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_18118" align="aligncenter" width="450"] Kokanko Sata in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

Kokanko Sata in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

Kokanko, born Sata, was born in 1968 in a village called Siekrolen in Mali, Wassoulou region. Her father was a blacksmith (as the name Doumbia indicates) and her mother was a jeli, a griot, charged by birthright with knowing history and keeping its memory alive in song. Kokanko inherited the jeli’s art, but tends to present herself in a different way, as a Wassoulou artist—like Oumou Sangare, Sali Sidibe or Nahawa Doumbia. Wassoulou singers typically proclaim that, for them, music was a choice, not a heritage. For Kokano, it seems, it is both.

Kokanko’s life in music began at age 10, when she began performing at local weddings. “I was playing calabash,” she recalled. “I would play when the bride was coming into her husband's house. When she arrives, some men would be playing djembe, and I would be singing and playing calabash. This is how I first came into music.”

[caption id="attachment_18121" align="alignleft" width="227"]

Kokanko, born Sata, was born in 1968 in a village called Siekrolen in Mali, Wassoulou region. Her father was a blacksmith (as the name Doumbia indicates) and her mother was a jeli, a griot, charged by birthright with knowing history and keeping its memory alive in song. Kokanko inherited the jeli’s art, but tends to present herself in a different way, as a Wassoulou artist—like Oumou Sangare, Sali Sidibe or Nahawa Doumbia. Wassoulou singers typically proclaim that, for them, music was a choice, not a heritage. For Kokano, it seems, it is both.

Kokanko’s life in music began at age 10, when she began performing at local weddings. “I was playing calabash,” she recalled. “I would play when the bride was coming into her husband's house. When she arrives, some men would be playing djembe, and I would be singing and playing calabash. This is how I first came into music.”

[caption id="attachment_18121" align="alignleft" width="227"] Kokanko Sata Doumbia playing her kamele ngoni in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

A few years later, Kokanko picked up the kamele ngoni. She notes that, although it is rare, women are certainly permitted to play this instrument. The kamele ngoni has its roots in the much older donson ngoni, or hunter’s harp, a sacred instrument veiled in ritual of protocol. “When one of the hunters dies,” Kokanko explained, “they organize an event and they play the donson ngoni. But this is only for old men, not for kids. So the young men, if they wanted to play that, they had to create another name: kamele ngoni. Kamele means ‘youth’ in Bambara.” This instrument is smaller and higher-pitched, and these days, players have added to its original six strings. But its most important feature was that anyone could play it—young and old, men and women. “So I tried,” said Kokanko, casually, “and everyone appreciated that. Soon they were organizing concerts, weddings, and now I'm playing the kamele ngoni.”

It’s worth noting that when Kokanko was born in 1968, the kamele ngoni had only recently been invented, and one of the musicians responsible for its creation—Satigui Dedjan—played at her naming ceremony. At an early age, Sata took the name Kokanko, referring to a small bird that sits at the edge of a village and warns travelers of impending dangers. Singers from Wassoulou are often referred to as songbirds, in part for their melodious voices, but also for this ability to deliver important messages.

Wassoulou music differs from the griot tradition in that artists tend to compose their own songs, rather than adapting them from a shared repertoire. Kokanko said she writes all of her songs, and they deal with social themes—trust, unity, betrayal. Although she was straight from the airport when we met, Kokanko sang three short songs for us in the Afropop studio. Here’s a video of the three:

Kokanko came to international attention thanks to a maverick British rocker, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), who included her in his experimental 2000 release Mali Music (Honest Jon's Records). Albarn recalled her, “singing and playing her ngoni on a boat on the Niger River in 2000—a beautiful and timeless moment.” In 2002, Kokanko became a member of Albarn’s Mali Music band, completing a European tour. In 2005, Honest Jon's released the CD Kokanko Sata that year, featuring Kokanko backed by a strong Malian ensemble. Kokanko’s only other appearance in the United States took place with a large ensemble Albarn assembled for a special Honest Jon's concert at Lincoln Center in 2008.

“Going abroad,” Kokanko said, “I learned a lot of things. I met people and learned from other experiences. I was very excited leaving Mali for another country. Staying at home, you add nothing to your experience, nothing to your knowledge. It's just what you have.”

[caption id="attachment_18115" align="aligncenter" width="595"]

Kokanko Sata Doumbia playing her kamele ngoni in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

A few years later, Kokanko picked up the kamele ngoni. She notes that, although it is rare, women are certainly permitted to play this instrument. The kamele ngoni has its roots in the much older donson ngoni, or hunter’s harp, a sacred instrument veiled in ritual of protocol. “When one of the hunters dies,” Kokanko explained, “they organize an event and they play the donson ngoni. But this is only for old men, not for kids. So the young men, if they wanted to play that, they had to create another name: kamele ngoni. Kamele means ‘youth’ in Bambara.” This instrument is smaller and higher-pitched, and these days, players have added to its original six strings. But its most important feature was that anyone could play it—young and old, men and women. “So I tried,” said Kokanko, casually, “and everyone appreciated that. Soon they were organizing concerts, weddings, and now I'm playing the kamele ngoni.”

It’s worth noting that when Kokanko was born in 1968, the kamele ngoni had only recently been invented, and one of the musicians responsible for its creation—Satigui Dedjan—played at her naming ceremony. At an early age, Sata took the name Kokanko, referring to a small bird that sits at the edge of a village and warns travelers of impending dangers. Singers from Wassoulou are often referred to as songbirds, in part for their melodious voices, but also for this ability to deliver important messages.

Wassoulou music differs from the griot tradition in that artists tend to compose their own songs, rather than adapting them from a shared repertoire. Kokanko said she writes all of her songs, and they deal with social themes—trust, unity, betrayal. Although she was straight from the airport when we met, Kokanko sang three short songs for us in the Afropop studio. Here’s a video of the three:

Kokanko came to international attention thanks to a maverick British rocker, Damon Albarn (Blur, Gorillaz), who included her in his experimental 2000 release Mali Music (Honest Jon's Records). Albarn recalled her, “singing and playing her ngoni on a boat on the Niger River in 2000—a beautiful and timeless moment.” In 2002, Kokanko became a member of Albarn’s Mali Music band, completing a European tour. In 2005, Honest Jon's released the CD Kokanko Sata that year, featuring Kokanko backed by a strong Malian ensemble. Kokanko’s only other appearance in the United States took place with a large ensemble Albarn assembled for a special Honest Jon's concert at Lincoln Center in 2008.

“Going abroad,” Kokanko said, “I learned a lot of things. I met people and learned from other experiences. I was very excited leaving Mali for another country. Staying at home, you add nothing to your experience, nothing to your knowledge. It's just what you have.”

[caption id="attachment_18115" align="aligncenter" width="595"] Kokanko Sata in Congo Square, New Orleans[/caption]

After her visit with Afropop, Kokanko headed south for appearances at the College of Charleston, the University of Georgia, and Furman and Duke Universities. This tour was organized by Julie Moore, the executive director of the Cradle of Jazz Project, and an adjunct professor of music at Furman. Moore has studied West African music and dance for 15 years, and in 2010 began uncovering new evidence that the Mande played a critical role in the formation of the cornerstone of black New Orleans culture during the 1700s.

Moore has been thrilled with the tour and Kokanko’s reception. Kokanko jammed with banjo maestro Bela Fleck and his wife Abigail Washburn. Said Moore, “She and Bela totally grooved, and she and Abigail did this amazing piece where Abigail was singing an old Appalachian song opposite Kokanko singing a Wasulu song. What I've particularly appreciated about the tour is her ability to connect in a meaningful way with people—letting her ‘songbird’ role be understood with her translator (Assigué Dolo) interpreting her songs on stage.” Kokanko has made for an electrifying presence in the classroom as well. Here she is, channeling her jeli roots, with an excerpt for the praise song “Fakoly,” in a University of Georgia classroom.

Kokanko told Afropop she very much related to the idea of connecting with related music in America—the core of the Cradle of Jazz concept. “Music is knowledge,” said Kokanko. “Think about dyeing cloth. This cloth is red. But if you add another color similar to that, another similar to that, it will still be the same color. So having a connection to jazz, well, it's another person who knows jazz very well. But I can add my music to that jazz, they can fit nicely. Maybe the other one will learn what I am doing, and I will also learn from the jazz player.”

[caption id="attachment_18116" align="aligncenter" width="601"]

Kokanko Sata in Congo Square, New Orleans[/caption]

After her visit with Afropop, Kokanko headed south for appearances at the College of Charleston, the University of Georgia, and Furman and Duke Universities. This tour was organized by Julie Moore, the executive director of the Cradle of Jazz Project, and an adjunct professor of music at Furman. Moore has studied West African music and dance for 15 years, and in 2010 began uncovering new evidence that the Mande played a critical role in the formation of the cornerstone of black New Orleans culture during the 1700s.

Moore has been thrilled with the tour and Kokanko’s reception. Kokanko jammed with banjo maestro Bela Fleck and his wife Abigail Washburn. Said Moore, “She and Bela totally grooved, and she and Abigail did this amazing piece where Abigail was singing an old Appalachian song opposite Kokanko singing a Wasulu song. What I've particularly appreciated about the tour is her ability to connect in a meaningful way with people—letting her ‘songbird’ role be understood with her translator (Assigué Dolo) interpreting her songs on stage.” Kokanko has made for an electrifying presence in the classroom as well. Here she is, channeling her jeli roots, with an excerpt for the praise song “Fakoly,” in a University of Georgia classroom.

Kokanko told Afropop she very much related to the idea of connecting with related music in America—the core of the Cradle of Jazz concept. “Music is knowledge,” said Kokanko. “Think about dyeing cloth. This cloth is red. But if you add another color similar to that, another similar to that, it will still be the same color. So having a connection to jazz, well, it's another person who knows jazz very well. But I can add my music to that jazz, they can fit nicely. Maybe the other one will learn what I am doing, and I will also learn from the jazz player.”

[caption id="attachment_18116" align="aligncenter" width="601"] Abigail Washburn, Bela Fleck, Kokanko Sata, Assigue Dolo[/caption]

Apart from the richness of the sessions and musical exchanges, the tour has also provided Kokanko with a welcome break from life in Mali at a difficult time. “Even before the coup (2012), before the crisis, musicians were having problems in Mali,” said Kokanko. “As soon as they created the memory card, people stopped buying CDs and cassettes. And we were not doing that many concerts. But during the coup, and afterwards, we couldn't organize any concerts at all. Absolutely nothing of our business was working. So me, I tried to create another job, dyeing fabrics to sell in Wassoulou in the villages. I have two kids, and in order to cover the expenses of these kids, I had to do this. Really, the artists were suffering. We are still suffering.”

[caption id="attachment_18123" align="aligncenter" width="575"]

Abigail Washburn, Bela Fleck, Kokanko Sata, Assigue Dolo[/caption]

Apart from the richness of the sessions and musical exchanges, the tour has also provided Kokanko with a welcome break from life in Mali at a difficult time. “Even before the coup (2012), before the crisis, musicians were having problems in Mali,” said Kokanko. “As soon as they created the memory card, people stopped buying CDs and cassettes. And we were not doing that many concerts. But during the coup, and afterwards, we couldn't organize any concerts at all. Absolutely nothing of our business was working. So me, I tried to create another job, dyeing fabrics to sell in Wassoulou in the villages. I have two kids, and in order to cover the expenses of these kids, I had to do this. Really, the artists were suffering. We are still suffering.”

[caption id="attachment_18123" align="aligncenter" width="575"] Kokanko Sata in New Orleans[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_18118" align="aligncenter" width="450"]

Kokanko Sata in New Orleans[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_18118" align="aligncenter" width="450"] Kokanko Sata in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]

Kokanko Sata in Brooklyn (Eyre 2014)[/caption]