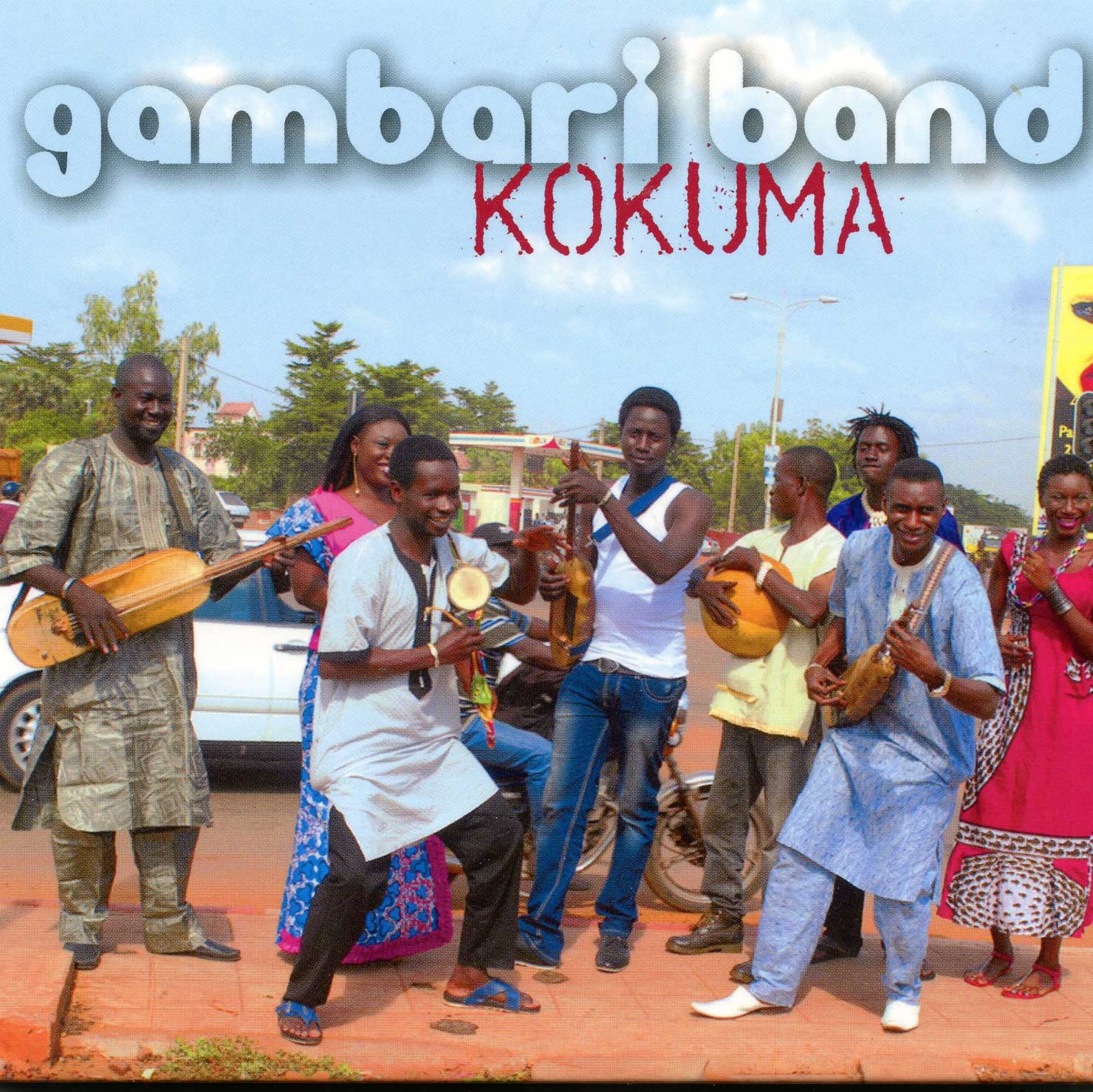

It was inevitable that, in the wake of Bassekou Kouyaté’s landmark band Ngoni Ba, there would be more Malian ensembles placing these stringed, fretless lutes of varying sizes at center stage. Gambari Band happens to consist of Kouyaté relatives who were formerly members of Ngoni Ba. No word here on the politics behind that, but the new ensemble definitely gives the current Ngoni Ba lineup a run for its money. With Oumar Barou Kouyaté taking the role of chief soloist and Kankou Kouyaté singing most of the lead vocals, the new band certainly echoes the original formula: rich weaves of ngoni textures, elegant solos on the highest pitched instrument, female lead vocals, and hot grooves that depend as much on interlocking plucked string lines as on the punch of drums or the snap of calabash percussion.

So what is different? Mostly subtle things. The overall sound is a bit cleaner. There are no electric guitar effects, in fact, minimal processing of any evident kind—just a crisp mix of acoustic sounds in which each voice inhabits a distinct place in the sonic tableau. Barou’s solos have a different personality than Bassekou’s. Barou is more melodic and less flashy. I can’t say either one is better, but they each have distinct characters, and given the prominence of ngoni solos—there is at least one on each of these 12 tracks—that is important. Gambari Band also uses more choral vocals, mostly combinations of female voices, though male voices can also figure, as on “Aw Nanaboye,” a song that announces the band’s arrival on the scene, beginning with the musicians sharing a joke with hilarious laughter, and unfolding into back and forth between the male and female choruses, and a righteous ngoni jam to end.

That hilarity is worth underlining, because there is a joyous energy that pervades this recording. Whatever issues caused these players to break off from Ngoni Ba, and despite the coup and and crisis in the north that had recently gripped Mali, when these tracks were recorded, the feeling of hope and uplift here is remarkable. The songs put forth moral messages familiar in Malian popular music: the importance of dialogue and communication, the dangers of gossip and defamation, and the value of music and social entertainment in a healthy life. The name Gambari refers to a rhythm from Mopti, home to an important band patron; the album opens with a song by this name with loping groove that seduces from the opening unison riff. Tempos vary throughout: “Baro” is a gentle canter, “Kele” sways like a camel moving slowly across the desert, “Zatou” is all cool funky swagger, and “Dakan” percolates with a slow blues vibe.

Most of the other tracks cook at higher temperatures, from a simmer to a boil. This ensemble is confident and tight at any speed. All the different pitches of ngoni have their moments to shine, though Barou’s high voice dominates the open spaces. There’s some lovely interplay between the two principle singers, Kankou and Massaran Kouyaté, notably on “Kokuma.”

This project extends Bassekou’s brilliant idea of building a band around ngonis. So even if they don’t break new ground, Gambari Band helps turn a phenomenon into a trend, and the band debuts with one of the most delightful and durable Malian recordings in recent years.