Edy Brisseaux is known in the Tri-State area as the “King of Raklasikobop,” a phrase which refers to his uniquely Caribbean fusion of styles (rasin, classical, konpa and bop). He started playing trumpet during his high school years where he studied with another prominent Haitian musician, Michel Desgrottes. At age 17 he started to play for top Haitian konpa bands such as Dixie Band, Skah Shah, Caribbean Sextet, Zekle and Freres Dèjean.

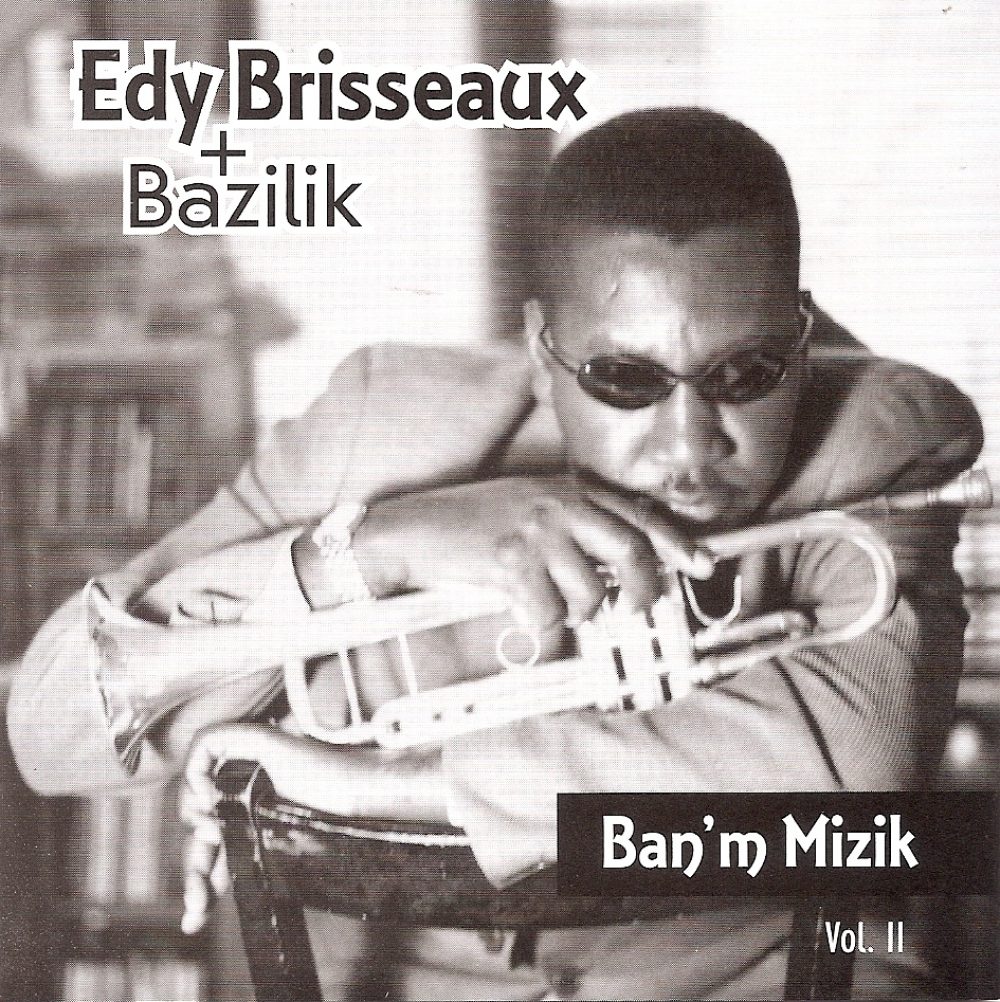

In 1987 he founded the group Bazilik and released a series of albums under the name Edy Brisseaux + Bazilik starting with 1992’s Move Vol. 1. In 1997 he introduced a new style of music called rabop to coincide with the release of Ban’m Mizik Vol.II and followed this with 1999’s Manman Vol. III The Christmas Show in 2000, Gospe in 2001 and Kik in 2003. During this time he was also involved with recording and producing other artists.

More recently he released The Raklasikobop Project which includes a wide variety of moods and styles with such songs as “Lese Pale,” “M’ap Marye,” “Oceano,” and “Sentiment” as well as a beautiful version of Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Nor does he shy away from jazz standards like Chick Corea’s anthem “Spain” or the Charlie Parker classic “Donna Lee.”

With a deep appreciation for the trumpet and its many moods, Edy has earned respect for playing gospel tunes at church and performing at the funerals of esteemed members of the Haitian community. He also finds the time to operate a mobile CD store which covers NY, NJ, and MA in the form of a van appropriately named "The Red Trumpet." As an educator, he pushes forward to spread the konpa message by means of online seminars and has published a short book on the subject available in English here. His many recordings can be found on Apple Music, iTunes and via his own website and his own Facebook page.

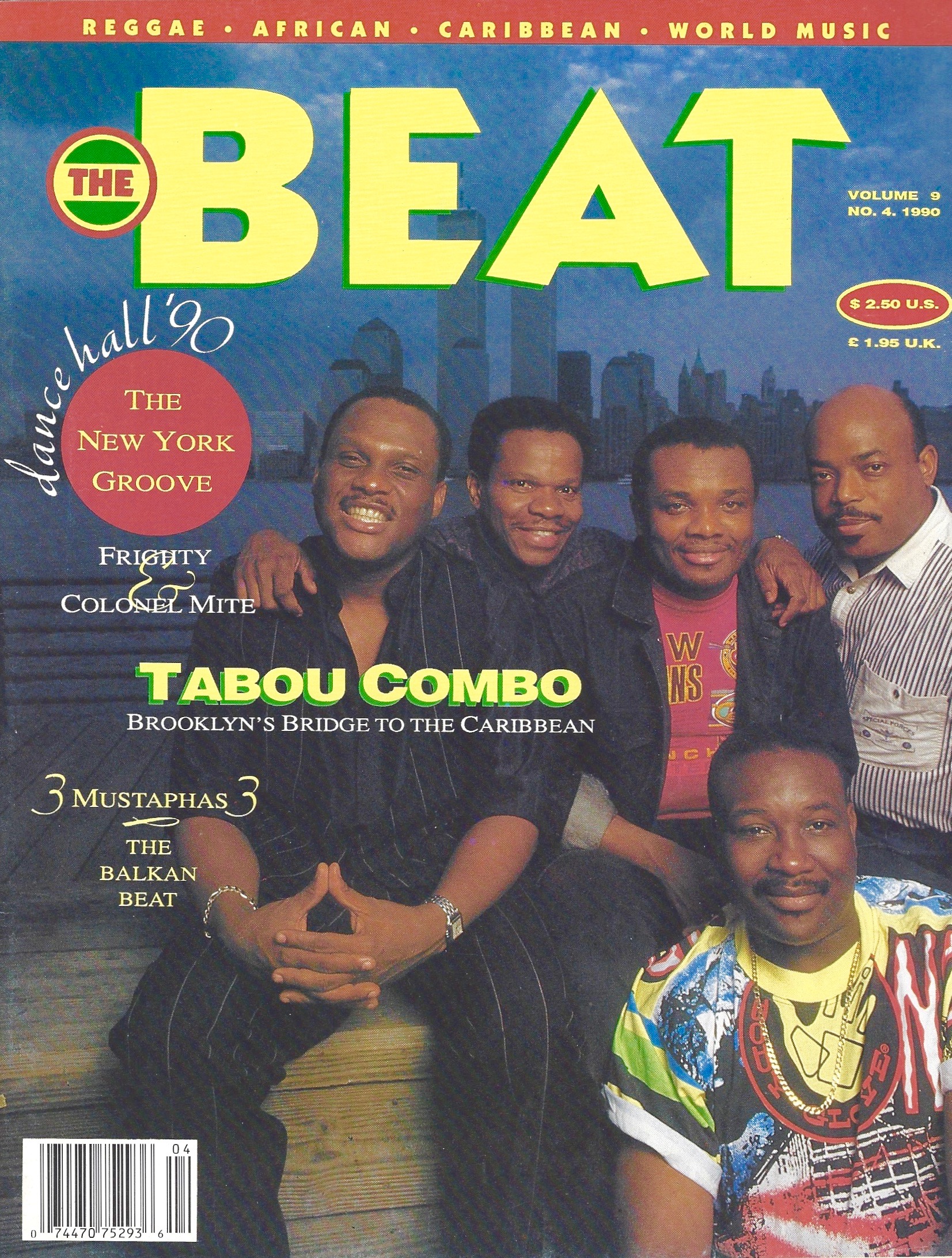

Brian Dring: Quite a few years have gone by since you were a guest on my “World Beat Radio” show on Connecticut College’s WCNI 90.9 FM. If I recall, you later invited me to catch your band when they opened for Tabou Combo at Brasserie Creole in New York. For those who may be unfamiliar with your music, where did you grow up and what were your earliest music influences?

Edy Brisseaux: I was born in Cap-Haitien, a city in the northern part of Haiti; but I grew up in Port-au-Prince. I always had a musical influence because my dad was a musician. He played the guitar, thus guitar was my first instrument as well. At a very young age, I learned to read music and began with the trumpet at a Catholic nonprofit marching band, then continued in high school and became lead trumpet by the 10th grade. Throughout high school I played anywhere there was music, from church to peristyles.

When did you get involved playing in konpa bands?

When I turned 17, I began to play with professional Haitian bands. One band manager-owner sponsored my studies with the great Michel Desgrottes. The first breakthrough in my career was when I was hired by the great trumpeter André Déjean to join his band [Les Freres Déjean]. From then, I continued on to play with bands such as Dixie Band, Skah Shah, Caribbean Sextet and Zèklè.

More specific to your instrument, which trumpet players do you admire or do you think inspired you in the past?

Of course André Déjean himself was one of my role models. Once I entered the world of jazz, the influence broadened from Miles [Davis] to Clifford [Brown] and all of the great cats such as: Dizzy [Gillespie], Donald Byrd, etc.

How did you end up living in Connecticut?

New York was a challenge because when I immigrated to the U.S., it was in the midst of the outsourcing of a significant number of jobs; even the government was using temp agencies. Thus, the competition was fierce and I did not have great mentors in New York at the time; consequently, I moved to Connecticut. I was always a suburban man. In Connecticut I was able to achieve my goal which was to educate myself. I did some social work and general science up to graduate school.

How has the live music scene changed since I attended your show years ago when your band Bazilik was opening for Tabou Combo?

I have been under the wing of Tabou Combo for the longest. They have been so supportive and in many ways they have inculcated in me the importance of going to school, especially Fan Fan Tibòt [Yves Joseph].

You went back to school at Western Connecticut State University’s music program. What made you decide to do that and how has it enriched your music? Did you study jazz, classical or both?

I studied jazz there, but I had previously studied jazz with Barry Harris in NYC.

I noticed that the weekly performances of your band Bazilik now include musicians from different backgrounds and not necessarily Haitian musicians. Was it your intention to recruit musicians outside of the Haitian community to open the music up to a wider audience or were you deliberately collaborating with your fellow students from the music program?

I met the non-Haitian musicians while studying at WCSU, where there is a great jazz program. Haitian-Americans tend to be open to collaborate with people across the spectrum. As a matter of fact, the U.S. has it all; it is a microcosm of world culture.

There’s a huge variety to the recordings released as The Raklasikobop Project, from the straight-up konpa of “M’ap Marye” to the rasin feel of “Bengiyon,” to the uplifting classical feel of “Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring” and everything in between. Do you plan to release these songs on future albums?

I am in the process of deciding about streaming, which is a plus. As a businessman, I prefer hard copy; the CD format is dead, but I am considering USB drives.

The song “Benygiyon” seems to mix a rasin beat with rather complicated jazzy horn arrangements. Can you tell me what the lyrics are about? Is this a traditional vodou song?

Indeed, this song is a hardcore rasin [roots] song with a common theme found in religions around the world, which is one reason why I stay at equal distance from all of them. The lyrics are about this invisible enemy that the adepts tend to complain about. But I ask why should they worry if what they believe in is so strong?

I like the song “M’ap Marye,” because of the sense of joy it conveys. So it’s about a guy about to be married? Has this song been recorded by different artists?

It is not my song, but rather by Richie Klass, a popular young band. Yes, it is some sort of love song with the common clichés.

Although you are mostly an instrumentalist, you do sing on a few tracks on every album, don’t you?

I do. I am a musician who became a singer; that is, someone who does not have the anatomic predisposition to be a singer, but I know the rationale for every note I sing.

I was feeling a jazzy beguine rhythm on “Lese Pale” and it turns out it was a tune written by the very accomplished Martiniquais pianist Mario Canonge. Are you familiar with other Caribbean horn players such as Guadeloupe’s Jacques Schwartz-Bart, Haitian-Canadian Joey Omicil, or Trinidad’s Etienne Charles to name a few?

I know them all. Omicil is of Haitian descent; but I share the same African heritage with the others.

I also recognized the name Chris Fletcher as the pianist on your version of this song. He is one of the most respected pianists on the Haitian music scene, isn’t he?

Chris was discovered while playing with Magnum Band; he also has the Haitian méringue in his DNA, thus we bond through this common heritage.

In your Facebook posts and your online seminar, you stated that Haitian konpa and Dominican merengue share the same genetic makeup. I found that an interesting perspective – can you explain further?

They are both offspring of the meringue, where the quintuplet is the driving force. The cinquillo, as it is known in Spanish music, is not based on the conventional concept. Rather it is a group of five notes that equal four (two short, two long). This rhythm structure is prominent in the Cuban contradanza and all the other forms that are in the same musical lineage. Furthermore, it has even influenced [American] ragtime and jazz as well. Thus, Haiti has influenced all musical styles in its proximity.