With the passing of Chuck “Baba” Davis, American dance legend and father of Brooklyn Academy of Music’s annual African dance series DanceAfrica, we celebrate the legacy he has left behind for the next generation to continue. One of those legacies is the Chuck Davis Emerging Choreographer Fellowship, an opportunity for developing choreographers to conduct research and further their artistic practice by traveling to Africa to study with one or more experts in African dance. The fellowship, in partnership with BAM, is monumental, as it combines the resources of established arts institutions, reputable choreographers and companies to invest in the artisans of tomorrow, specifically those studying African dance techniques. In April, Akornefa Akyea, Afropop’s director of new media and operations, and I attended the inaugural showcase of Kwame Shaka Opare, the first beneficiary of the fellowship, presenting .theScope.theWork.theProcess: GHANA. After his presentation, Opare and I spoke on the phone to discuss his current work, the career routes he has been on and where he is planning to go next.

Born and raised in Washington D.C. and New York, Opare has been a longstanding member of the African dance community, a connection fostered at an early age. In 1989, Opare, then 14, became a senior company member of the KanKouran West African Dance Company. Under the direction of Assane Konte, cofounder and artistic director of KanKouran, Opare transformed his passion into a career. Throughout his childhood, Opare recounted, studying West African dance was encouraged by his parents to foster a cultural connection with his heritage as a member of the African diaspora. Unlike today where there are constant budget cuts chipping away at arts programming, dance and music were part of the curriculum and pedagogical structure of his schooling. Opare explained that “[Dance] wasn’t a separate thing.” Through KanKouran, Opare was able to see and learn under master dancers and national companies touring the United States, especially through KanKouran’s National Conference and Concert featuring world-renowned African dance performers, such as Youssouf Koumbassa, Amadou Boly and Marie Basse. These visits allowed Opare to not just dance with them in a class setting but in a rehearsal setting as well. The difference in context is that rehearsal allows a student to become not just a performer, but be recognized as a practitioner and an individual who can be trusted to display the technique with integrity.

Opare’s work took him to New York where he began dancing with Marie Basse’s company Maimouna Keita, freelance choreographing for traditional West African companies, and teaching at studios such as Bernice Johnson’s Cultural Arts Center, Djoniba, and the Harlem Bathhouse. Touring with European pop star Gala and the musical production STOMP! were Opare’s first steps into contemporary modes of West African movement, eventually leading to the founding of his own contemporary West African dance company, DishiBem Traditional Contemporary Dance Group. Instead of just being preservational, Opare frames his practice of African dance by presenting it as contemporary folklore. Whether his work is about education, women’s rights or human rights in general, Opare utilizes West African dance styles in contemporary modes of performance to tell stories based on these social commentaries.

The showcase of Opare’s time abroad was a multimedia presentation capturing a poignant balance between the instinct to keep hold of the traditional and the urgency to lead the contemporary. The performance began with a short film of monologue updates and the progression of his studies in Ghana, funded by the fellowship grant. With a staccato editing style, Opare took us to the geographical locations through which he traveled, from Accra to the north. Shots of rehearsals with the National Dance Company of Ghana and music lessons would cut to images of young dance crews and community gatherings with men atop horses as both rider and creature swayed to drum beats.

In our conversation, Opare explained that the video was another mode of expression that allowed him to show the cultural jumps that he went through during his time working with the National Dance Company and with his colleagues as he adjusted and pushed through research to figure out his intent.

The video also conjured a humility in Opare’s approach, as we saw him struggle in his music lessons, at points head bowed in frustration. Nonetheless, Opare persevered until we finally heard him make sense of the music (and play in tune). During the talkback after his performance, Opare recalled the first day of rehearsals with the National Dance Company: In the middle of staging a production, the director told Opare to get up and stand in an empty space among the company members. Opare lived all of our greatest fears--yet oftentimes the best way to learn and grow--as he was thrown into the middle of the rehearsal and told to keep up. Thus began his short-term residency as member of the National Dance Company.

As Opare filmed himself, he was able to play with the tension that his work existed both in the present, at the time it was filmed, and in the future, in anticipation of it being shared during the April performance.

Returning to the showcase performance following the end of the video, the stage was relit to reveal a giant umbrella entering on stage right, lined with trim, presented sideways facing the audience and obscuring the bodies of the 10 pairs of feet that shuffled across stage. The umbrella was lifted up to let the drummers take position; the umbrella and its party continued to shuffle.

The umbrella eventually closed to reveal Opare, enrobed in traditional batakari and grande bubu tied by a piece of kente cloth, flanked by four female dancers. Steadily, Opare removed two layers of garments and suddenly jumped into the rhythms the drummers struck up with his accompanying dancers.

The dancing began with various rhythms traditionally performed for royalty: beginning with the king’s dance, Takai from the Dagomba people of the north. Takai shifted to atsiabegkor, an Ewe rhythm, into the dance of the Serakholé people, techniques both learned during his travels and decades ago. Throughout all these dances Opare masterfully interwove techniques not traditionally performed to the rhythms; laying 4/4 time over 6/8 time rhythms such as Sorsorne dances from the Baga, one could even catch Sounu, jumps from Frontofrom, Awabeko, and Djinafoly, a Malian dance for the ancestors.

In our phone conversation, Opare talked through all the rhythms he sampled during his performance, singing the beats, switching between sounding out the instruments to counting out the steps. By switching between movements that came from not only Ghana but also Mali, and even bringing together movements with different purposes and interweaving them with others, Opare found that his research was also finding movement commonalities between dances that were not known because of colonization. Opare was able to infuse contemporary into the traditional movements by creating discreet moments, i.e., a finger snap sneaked in between the drums, to act as audible reminders that, despite the rhythms being traditional, the work as a whole was about the present.

Every element of the stage served two purposes, to show the preserved and to simultaneously re-present these dances as contemporary dance. Throughout the show, the umbrella was spun by its bearer. Opare explained to me the spinning of the umbrella was a symbol of this performance being an opportunity to synthesize and spin out his experiences from Africa.

The audience was privileged to witness the final piece, a sorrowful commemoration of Opare’s mother who had passed in the last year. This final piece was under debate as to whether it would be presented that night. Over the rehearsals Opare had been unable to lay down concrete movements to this piece as it still lay close to his heart. However, Opare took the stage with two of his female dancers, Maisha Morris and Sanchel Brown, and began this commemorative work to an alternative indie song entitled “Green Spandex,” by Xavier Rudd, opening and closing with projected images commemorating his late mother. Morris and Brown wore incredibly large-brimmed hats, made out of plastic bags, inspired by the hats worn by women in the Ghanaian marketplace. The women flanked Opare and all three dancers were crouched down. Due to the diameter of the hats, the women’s bodies could not be seen but shivers of their movements brought life to the hats, making them an extension of the dancers themselves. What resulted was exactly what Opare’s intent had been: a re-presentation of a masquerade dance calling upon an ancestral spirit. As the hat wearers improvised, Opare knelt, groaning and expelling wails of despair, not so much performing but presenting his process of mourning through the means he knows best, music and dance. Some initial thoughts on this piece were to have the dancers extend their arms backwards, reaching to grab something, only the elbows ever getting close to moving forward. During the showcase the dancers captured a tension, were they reaching back trying to grab at something or was something pulling them?

From our conversation, I realized this physical enactment of reaching back versus being pulled back encompassed the paramount struggle of African dance. Both the fellowship and Opare’s work are grappling with how to preserve African dance, compel dance institutions to recognize African dance as on par with Western techniques like ballet and modern, and simultaneously employ African dance as a contemporary technique.

Initially, Opare described the struggle throughout his dance career, “how to tell my story….[if] I’m not a ballet dancer…I’m not doing…quote on quote ‘modern,’” so the challenge became how can one tell contemporary stories, “using West African styles?”

During the talkback, Opare vehemently expressed that the codification of African dance needs to be the priority for prominent practitioners of African dance, explaining: "In order for West African styles to be effective in this [contemporary] mode of performance, they really need to be studied at a level that gives us, as contemporary performers in Western society, gives us access to these techniques so that we can utilize them to say whatever it is we want to say and not compromise the integrity of the technique." Opare jokingly described how the codification would be establishing something like a West African “first position,” which would be like a position found in the modern dance style of Lester Horton: back straight, pelvis tucked under and aligned with shoulders, knees slightly bent, and arms dropped to the side.

Opare fleshed out that statement a bit more in our phone conversation, elaborating that codification is specifying the way that movements and the dancer’s body must be aligned, coordinated and articulated in order to execute the African dance technique correctly. The interaction between Western and Eastern culture makes transferable teaching techniques crucial in order to preserve the integrity of the form as it moves across borders. Opare recounted that he was never able to fully appreciate jazz technique, which he describes as North America’s original classical music, until he learned trumpet. Only when he was able to access an art form, playing trumpet, could he appreciate the cultural and technical components of jazz while still maintaining its integrity.

We discussed that a mark of a phenomenal teacher is one who can switch between explaining a step in relation to the drum and the break, just as Opare did throughout our interview and the showcase talkback, suddenly talk-singing to explain the movement, but also able to explain the step in counts. A teacher’s ability to code-switch, to explain and teach a dance form to any student, any dancer, whether in a Western style of teaching or Eastern, is a sign of mastery. This type of code-switching is also a pedagogy that needs to be encouraged in dance studios in order to continue African dance’s recognition as both a traditional mode of dance as well as an avenue for contemporary performance.

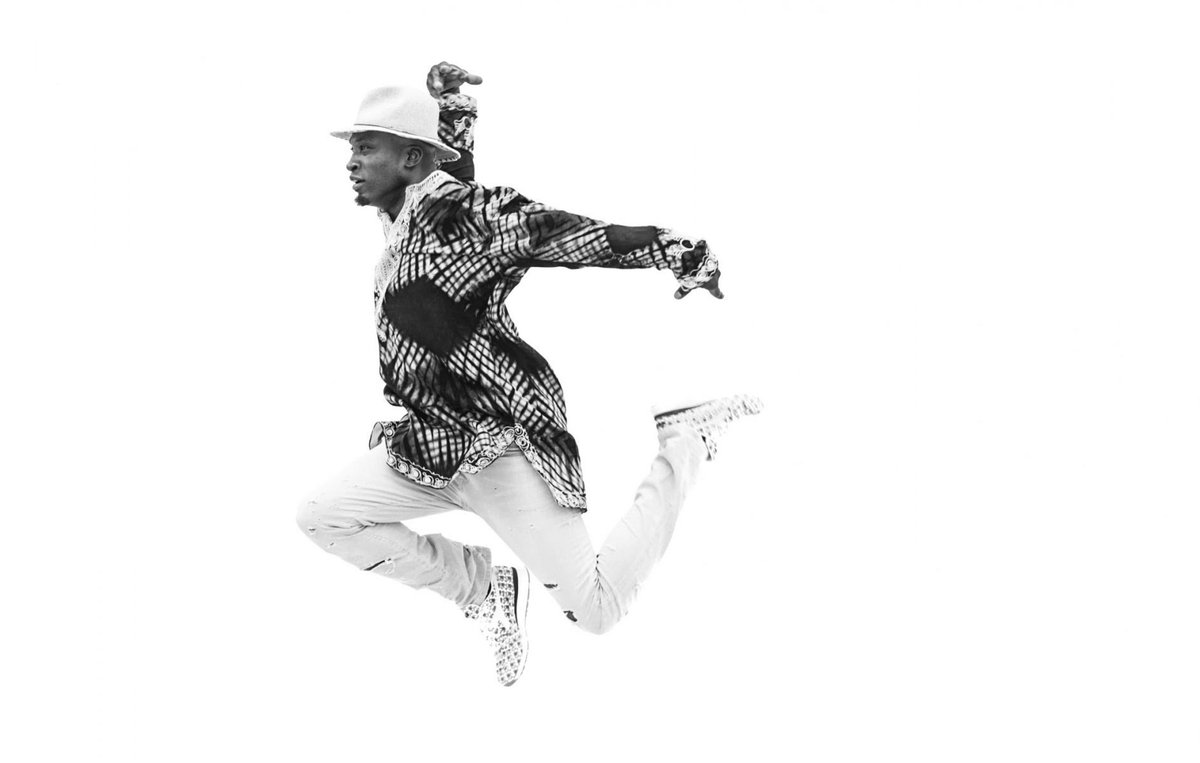

Kwame Opare receives the Emerging Choreographer Fellowship from the late Chuck Davis. (Photo courtesy of Kwame Opare)

The issue of recognition and respect for African dance not only applies to the teacher and teaching style but also to the investment in choreographers like Opare and the studios that make African dance techniques accessible. I asked Opare whether he had achieved what he sought to do in taking on this fellowship and what mark he hoped to leave for future fellows. Opare explained how the fellowship is in response to the marginalization of African dance, therefore for those who wish to pursue this avenue it requires a pre-established commitment and mastery of African technique(s): "Too many people out there that have been toiling and working at this for someone who hasn’t been a part of this [African dance] to get it [the fellowship]…we don’t serve the spoken expectation of the fellowship and what Baba Chuck would want if we do that [award the fellowship to a novice of African dance].

Opare described the showcase as akin to “an artist winning their first Grammy.” The reception of his work echoed back Opare’s intention. As he described in our conversation, an anxiety for all artists is that once an artist performs their work it no longer belongs to them. The resonance among the audience of his work in the showcase and consistency in the audience’s interpretation affirmed Opare’s mastery as well as the refinement of his style. As one audience member described the performance, “It was in a contemporary mode of performance but that it was unapologetically West African in the movement.”

Opare is moving unapologetically forward. He will continue to work on his performance through the support of the fellowship and on fundraising efforts to further his endeavors. The showcase performance confirmed what many of his teachers had recognized in Kwame Shaka Opare since his youth, an artistry that is not only sustained by a technical mastery but is rich with nuanced creativity and innovation that is incomparable to others.

In his closing words during our phone conversation, he shifted the urgency toward investing, a call for arts organizations to provide rehearsal space to individuals, prioritizing those who are practicing marginalized dance forms; going to local studios and local artists and learning from them. Organizations, such as the Asase Yaa Cultural Arts Foundation, usually offer affordable classes--all they need is us to take them. Shifting his gaze toward higher education, Opare reflected, “I don’t fit the mode of what people inside the dance departments look like and I really want to change that.” Opare is interested not only in increasing African dance representation in the faculty repertoire but also being a model for young people, especially boys, to show them that they should not feel pressured to fit a certain gender role in dance, i.e., that the only masculine form of dance is street dance or hip-hop. Opare wants to change the way that looks and exemplify to young people that all artistic expression is theirs for the taking, the key is being prepared to meet the challenge with commitment and respect.

A seemingly surprising moment occurred at the end of the showcase when an audience member, moved by the performance, stood up during the applause and laid a tip down in front of the bowing performers. Emphasis on “seemingly,” tipping the artist is normal in African culture, expected especially after the type of performance Opare and his company shared. Opare’s frustration and the anomaly of a fellowship such as the Chuck Davis Emerging Choreographer Fellowship begs the question: are we really giving what is owed to not only show appreciation for the arts but also ensure its longevity in preservation and development as well as encouraging practice with integrity?

All I know is there was cash spilling out of the hats by the time we left, I have a new list of studios and companies to check out, and there is definitely more we can expect to see from Kwame Shaka Opare in the near future.

Chuck Davis Emerging Choreographer Fellowship Showcase Cast:

Drummers: Yao Ababio, Opare Agyeman, Kwabena Agyeman, Kweku Amantey Opare

Dancers: Kwame Shaka Opare, Maisha Morris, Sanchel Brown, Kofi Assane Opare, Kyra Ferguson, Candance Sumpter

For more information on Kwame Shaka Opare, updates on his work, his TED talk on youth advocacy and his experiences in education, or for ways to support innovative choreographers like Kwame Shaka Opare, check out the links below:

Website

https://twitter.com/kwameshaka?lang=en

TED Talk: “Disrupting the Miseducation of African American Youth”