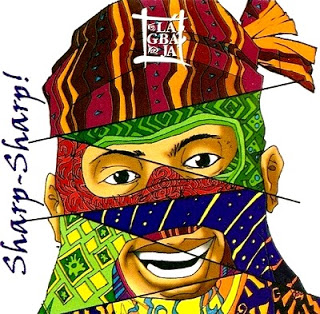

Lágbájá is one of the more unusual voices in Nigerian popular music. Since his arrival on the scene in the early ‘90s, he has stuck with his habit of not showing his face as an artist. His music is equally chameleon-like, shifting between Afrobeat, juju grooves, funk, jazz, Afro-Cuban, gospel—whatever suits his purpose. And with some 10 albums to his credit, he’s pursued a lot of purposes. Lágbájá toured the U.S. in the summer of 2015, and Afropop’s Banning Eyre and Sean Barlow caught up with him in Philadelphia. The conversation began with the artist’s career and recent work, then broadened into a look at today’s Nigerian music scene.

Banning Eyre: Hey, Lágbájá, great to meet you. I know that Sean once interviewed you in Lagos, but for folks who are just catching up, give us a little bit of your story, in particular, this choice to wear a mask, even during this interview!

Lágbájá: Yeah, Lágbájá basically came about when I started my career musically, and I wanted to focus on social politically conscious music. Before that, I had been playing music, and also recording in a studio, as a producer for commercials. So when I started that with the intention to focus on socially conscious music, I wanted an iconic image, something that would communicate the essence of what I am all about. Even if you don't hear my music, you ask a question when you see a mask. Why is he wearing a mask? And that would lead you to the story of the mask, which is simply something that stands for the so-called common man's facelessness and voicelessness. So that's how we started. And we had our first album.

What year was that?

1993.

And here we are 22 years later.

Oh yeah. And it has been upward ever since.

Your musical style is really kind of a blend of things, isn't it?

Yeah it is. I started out being a music lover, so I had a lot of influences. I grew up in a place we had a lot of drums, so the drums are the beats in the grooves–I will say still constitutes my major influence. I remember as a kid watching festivals with masquerades. Who knows? That might also have influenced my thinking. But the drums I find to be the most potent and the most important part of our music.

When you listen to the music of King Sunny Ade or Fela Kuti, or many other musicians from West Africa, I would think the most distinctive part of it is the drumming. In the Francophone countries, they have a lot of melodic and harmonic instruments like kora and ngoni. We are very heavily rhythmic people, so I found that I couldn't just sit still and say I will play Afrobeat, or I will play juju. Because I have all those rhythms and, because I love music, I studied them. They became part of my music. So you will hear a song that has a connection to Fela’s beats, but it's much bigger than that.

Just as you have very sophisticated harmonies here in the West, in the same way, we have sophisticated drumbeats. As a matter of fact, the drums are the most important part of the music. That's why you could see a band back home that is only drums and vocals. And that would be the whole show.

Like fuji music.

Like fuji music. That's it. Well, fuji music before. Now in the bid to so-called modernize, they have been dragging Western instruments into their music, but it used to be just the drums, all kinds of drums: Barrister, Kollington and all of them. I come from the Yoruba culture that has produced a lot of incredible groove music, like the apala music of Haruna Ashola, the sakara of Yusuf Olatunji. Of course everybody knows Fela Kuti, but really they should know that it's the same Yoruba roots that gave those rhythms. He just made them a little bit more sophisticated by having his funky influences in there. Of course, the juju of Ebenezer Obey and King Sunny Ade—these are all Yoruba rhythms. So I wanted to be the one who, after researching out of love, was able to present a show that takes you through those rhythms.

In the 23 years that you have been on the scene, popular music in Nigeria has changed a lot. We know that Nigeria now produces the biggest-selling artists on the continent. What is your experience of the new music? And have you been able to keep your audience in the face of all this new stuff coming up?

Yeah, we've kept our audience loyal. But younger folks are more attuned to the newer sounds. There is the noise, as happens with every generation where people say, “The new music is not music. It's bad music. It's noise music." I don't subscribe to that. New music is new music. There is always new music. Even when Afrobeat started, for some people, they would rather have kept it highlife and palm wine. So there is always new music, and young folks are more attuned to that. It is their sound today. As a matter of fact, I think what’s mostly responsible for that music is American hip-hop influence; and number two, the prevalence of technology. That's why it all sounds the same. It's mostly music made by producers and single stars in the studio. It might be difficult for them to reproduce the sound live. The beat has become a clichéd beat. It's based on one main, well, two main rhythms. The second one just came out about eight or nine months ago.

That's more like a 12/8 kind of rhythm blending with a 4/4, which can even be traced to some Congo, Zairean, salsa, Latin American, clavé beats, but played on the snare drum and kick. This became a huge one. And because you could just program the sounds, and you could share the sounds, it became easy to copy.

Two rhythms? That’s interesting. Tell us more.

The new one is the one that started with this hit by Davido, “Aye.” They still call it by the same name: Afrobeats. They put an “s” after Afrobeat, which I think is borrowing from Fela’s title. So they called it the same thing, even though the rhythms are different. Before that it was a straight 4/4. [Sings] But instead of the side stick that you would hear that beat on calypso or soukous—heavy snare. It's an exciting beat, there's some lovely music. That's why I said don't subscribe to the idea that it's all noise, even though you do find noise. But there's very good stuff too.

Let's talk about your more recent music. Tell us about your newest CD.

The most recent one is very political. It came down about two years ago, it's called 200 Million Mumu. It’s like a wake-up call to the people. The Nigerian population is said to be about 170 million. I picked 200 million, because it was more poetic, but it's still referring to the population of Nigeria. Mumu itself rings offensive in the minds of people, but what it means is, "Wake up from being fools." I’m telling 200 million people it's time to change what we are doing. And the basic message behind the whole series—because it comes in three parts—is simply that you can't keep blaming the leaders all the time. You should see by now, many years after military rule, that something is wrong. We need to ask ourselves what we need to do as a people. It's a call for the citizens to play a main role in taking charge of their destinies, and not expecting the leaders to be Father Christmas or whatever. If you don't question them, if you don't put them on their toes, there will be impunity.

Do not be 200 million cats who are following the herd in some funny way and just keep complaining. The whole world keeps hearing stories about Boko Haram and murder and terrorism, things that never used to happen. And you have a government–or you had a government, had, because in a few more weeks they will be out–who didn't know what to do, or didn't believe it could be that bad. That you could have a situation where over 200 schoolgirls are kidnapped over a year after, you still couldn't find them.

This is probably the first time that such a heavy, political statement is being directed at the populace, not the leadership. It would be easier to always point at the leaders, but I'm saying this is no longer a military government. The so-called leaders are from amongst us, right from the local governments right up to the top there. So something else is wrong.

That’s interesting. I'm hearing a similar message from other politically minded singers too. Like Thomas Mapfumo of Zimbabwe. He's also telling people not to just rely on leaders to solve problems. Now, earlier this year, you had an election in Nigeria. It sounds like it went quite well from the way it was reported internationally. The country had the ability to steer away from the ruling party. What's your take on this?

By and large, it was truly a successful election. You had the challenges no doubt, but by in large, it really happened. And why it's such a big shock is that nobody expected it would happen with such ease. But it really happened. I think the message is sinking in. The message has been coming up gradually in people's consciousness–there has just got to be a change.

There was a lot of noise by the government in power because they had very loud PR people to try and confuse the people, as they usually do, and blame everything on religious differences, on ethnic differences. It’s unbelievable what they tried. But in spite of all that noise, people made their voices heard. It’s a sign that the message is sinking in. People, especially young folks that had access to social media, really played a big part.

Were you surprised by the result?

No. I was hoping for that. If you go to my Facebook page, and you look at the post that I did weeks before the election, it was like, "It's got to be now. Or it will never happen." Now I think the only surprise was that the outgoing president was wise enough and good enough not to have gone the way of typical, African, sit-tight presidents, but to listen to wise counsel. It wasn't going to be easy. He wasn't going to do that, from what we heard. And he still could have rejected wise counsel. For that, we actually owe him, I tell you. Because it would have been really serious trouble.

He accepted his defeat.

He accepted early—that's the main thing—even before the final announcement, he accepted early. That's unheard of. He nipped in the bud all kinds of trouble, just like that. Everybody was ready for people moving away from potential trouble spots. The ethnic noise, the noise about religion, really got into people's minds. So that was a good thing, and I hope it really brings a change that people are looking for. And the message of 200 Million Mumu, as I keep saying, now that there is a change of government, it's not automatic yet. Even the new government, you've got to put them to the task. You've got to make them stand on their toes. You've got to keep pushing them, asking questions, or else nothing will change.

Sean Barlow: Where do you perform in Nigeria these days? Do you ever play weddings?

We play everything. Our whole career depends on live gigs these days. You can't make money from recordings. You can't. So we play for whoever can afford us.

Let's talk more about the songs on this new CD.

Actually, there are eight tracks on it. And it follows the same typical Lágbájá philosophy that you can't just blow your life shouting about problems. You've got to have fun. So the fun songs on the CD are "Knock, Knock, Knock,” which is a lovers’ thing. And “Omo Jayejaye,” which is about a person who loves the good life, and when you overdo it, what are the consequences? Those are the fun songs.

Then you have this special song for me. Two of my favorite artists are Bob Marley and Fela Kuti, so I decided to do something with the concept of, "Can you imagine Fela Kuti doing a cover of a Bob Marley song?" To me, they have similar messages and thought in similar ways about the people. So I took "Redemption Song," the lyrics and melody of Bob Marley, and I did them in a style that is reminiscent of Fela Kuti. Then I added the Lágbájá drums. I call that "2 African Soldiers."

Then I have “200 Million Mumu Part 1,” and “Part Three.” “Part Three” speaks to the people. It's about eight years ago our former president, Obasanjo, and his quest for a third term—exactly what is happening now in Burundi. It's this message of people taking charge of their lives. Then I have a church hymn. It's still part of the same message, and the whole story of that satire is, "We love to shout about our religious beliefs and how good we are as Christians, and how good we are as Muslims, but it doesn't reflect our day-to-day lives." I also have a second song, "Dust to Dust,” that is also a hymn. So now we have two hymns with the same principle.

Hymns, eh?

Now, Lágbájá without the mask is a Christian, so I am not deriding spiritual beliefs. I have my strong beliefs too. But I am saying, "Your life should show you really are. We have millions of churchgoers. The largest events are usually religious gatherings, and yet that wouldn’t show in our daily lives. You have an aspiring president going to a religious event. Is it about doing the right thing? Or just playing with the intelligence of the people? So if you hear those two hymns there, that's their role in the satire of 200 Million Mumu.

Then "Dust to Dust" is a little heavy. The message is, "If you remind yourself all the time that this earth life is going to end, and someday you will be dust, it should help you in doing the right things in knowing that time is short. In that short time that you have, you can have a lot of fun, and yet, you can also contribute a lot to society.” That's the story behind this CD.

So you're working on a new CD now.

I am. The working title of the new CD might change, but now it is Electro Africano. Usually people call my music Afrobeat. I never argue with anybody. Who cares what people call my music? I think it's because they can see some similarity between my message and Fela’s. But when it comes to the rhythm, there are many other things happening in the style itself and the influences. So I call my music “Africano,” and I'm alluding to the different roles that the drums of Africa play in our music. But I’m also using those atmospheric sounds. They are very African, even though they are mostly made with the synthesizer, but it’s the sensibility. You know this guy who plays electric guitar with Youssou N’Dour?

Jimmy Mbaye.

Jimmy Mbaye, yeah. He plays an electric guitar, but with the sensibility that would remind you of the kora, with those muted notes that you hear on native Senegalese instruments. Now, if you listen to the synthesizer, it's a little bit less organic to control than a guitar, but if you will sit down and study enough how to do good sound design, you will be able to bring out some incredible, very African stuff. So it's my perspective of a very modern instrument, but that can create very beautiful soundscapes. So when I say Electro Africano, it doesn't mean it's going to be like dub step or that sort of thing. It will still be my rhythms, but with those subtle harmonies, those floating sounds. You could have these beautiful soundscapes. It will be more dance. If you can imagine Calvin Harris, that Scottish guy who is a big producer in electronic dance music. Imagine someone like that, and then add that to Fela Kuti and King Sunny Ade and the traditional drums and grooves of Yoruba, and you will imagine what I'm talking about.

I can't wait to hear that. We have been hearing some of the new music coming out of Mali that's a little bit like that. They take the music of the balafon, but they're playing it on computers. It still sounds like balafon, but it's electronic, and super fast. It's nice, traditional and modern at the same time.

Yes. The danger though is you've got to understand the technology very well. And understand how to do good sound design, or else, you end up sounding really stiff. Inorganic. Un-African.

Sean: In this country, we have a new dialogue going on with African music. I remember back in 1983 seeing Sunny Ade at Zellerback Auditorium, selling out 2,000 seats on his first time in the Bay Area. I fell in love with the music right away, and that helped inspire Afropop. Then there was this wave of Congolese bands coming here, Fela with 28 people on stage, then the Malians and the South Africans. Now we have this new generation of musicians, people like Davido and Wizkid, and they appeal to young Africans who want to be different than their mothers and fathers. But a lot of the audience for African music here is older, and not so tuned into hip-hop aesthetics. So I am fearing that African music is going through a period where there's going to be less acceptance and less opportunity here. There's a kind of schizophrenia going on. In order to gain one part of the audience, you have to lose another. Do you feel this, and if so, how do you deal with it?

I think the easy thing, or the likely thing, if I'm going to predict using my prophet heart, I think there are going to be two different audiences. I'm talking about here, not back home. I think here, we are always going to have our audience, music lovers who understand diversity and know that there is more out there. They don't know the language but they just like what they hear. That audience is still going to be there. However, I think that the younger artists to are going to have their audience. I think they are probably going to make the quicker splash, which eventually will lead more people to deeper stuff than they do. Because the way the new music works, it's not about the music; it's about the hype. So all you need is somebody who has a hit with all the hype. For example, about two weeks ago Jay Z sent his company to Nigeria to go search for new music.

I just read about this.

Yeah. So all you need is somebody makes a break, and they say, “Hey, what's that?” And then they start asking, "What's the history behind that?” So that could serve as some kind of bridge to the deeper stuff, as well as creating their own market. I'm doing the deeper stuff out of conviction. If you will sit down and think in terms of commerce, you would change your music, but then you would be fake, because it's not you. It's not real. Already, those folks are packing 2,000 person venues in London. Now London is more focused. There are, like, lots of people. In the U.K., we have like London, Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool. They have large crowds. But especially in London. We had 2,000 people at Brixton Academy.

But America is huge, a lot bigger, and it needs a different kind of marketing. But the same way that the involvement of Jay Z and Will Smith took the Fela! musical from the obscure theater to off-Broadway, it's the same way that the right marketing hype would easily get that young audience there. The only danger is the new fans who listen to this music might not know that this is not the real thing, and that this is like a slapback echo of what was the original American hip-hop culture. It's less about the music than the hype. It's about the bling. It's about showing money and videos about girls shaking their behinds and stuff like that. It's the same mentality. The language is just Nigerian.

Some of the beats are also Nigerian. Sometimes too the performers remind you of hip-hop too, because half of the time it's a CD, and about four guys on stage singing and hyping a dancing and stuff like that. It's not even a real band. I don't have fears that is not going to be successful. I think it will be. But I hope, ultimately, it will help people to discover the real thing about African music.

I like that idea about people being brought in by the hype and then going deeper.

As a matter of fact, you know how I got into jazz? Very strange. Very strange. I was in love with “Samba Pa Ti” by Carlos Santana. I was in love with "Black Magic Woman" and "Evil Ways." And then I got into this instrumental, “Samba Pa Ti.” But this was rock. Maybe like soft rock. But then I found out suddenly that there was instrumental music, and they used to call it jazz funk. I went into jazz fusion and I found Grover Washington Jr. Wow! And then I found there was Bob James. And then suddenly, I discovered there someone called John Coltrane. So, you know, I think it's a matter of who the audience is. Why do you listen to music? Is it because it's a fad and you want to have fun? Or is it because you love music? If you love music, you will start digging deeper. I started discovering there were more stories.

It's like our generation who start with Elvis and the Rolling Stones and all that, and then they discover the blues.

And then suddenly, there is Mali! [Laughter]

Yes. Exactly! Africa.

That's it.

Sean: Well, I'm glad to hear you say that you think people will be led to the deep stuff. I've seen that some musicians from Nigeria come here, they don't even sing. They just get up in front of their tracks and people go crazy. Because they see their guy.

It's the hype. It's about the glamour, more than the music. The hits don't endure. They might be there for maybe a year at the most. They are churned out in large quantities, but they are impactful. And the audience is not thinking music; they are thinking about the glamour: the American style, black music glamour, which includes hip-hop and soul—all these things that you see on TV or the blogs. Some Nigerian blogs, every day, there will probably be 50 percent of it would be the bling and glamour of American popular culture. So you will see the Kim Kardashians. The same stuff you would see about Jayzee and Beyoncé. And these are blogs that are heavily subscribed to. You have young folks putting out pictures on Instagram to show dollar bills on the table–the same thing you find with hip-hop musicians doing. Even the music itself–it's mostly about girls and money and the good life and alcohol and partying and stuff. That's it.

Sean: Christian mommies and daddies must not like that. There might be a little conflict between junior and daddy there.

[Laughs] That will always be there.

Well, you know, we have a lot of young producers working for us now. We have this dialogue all the time. On the one hand, I really respect what you are saying that the older generation is always good to find things to object to a new music. But at the same time, I wonder come along the lines of what you were just saying, is the character of the music actually changing. When you say the songs don't last for long. I think, if the songs go by that quickly, is anyone even really going to remember them and care about than in 10 years? I wonder.

You don't know, but I would guess that it wouldn't last that long, because all the time, even when there was Fela huge in the market, and there was juju and fuji, you always had this American-influenced pop-style stuff happening. If you look at our history and the fact that all those big hits have endured until today, it is a pointer. It's likely that this so-called quick, fast-food music wouldn't endure for so long.

That's one side. Another side is the role that the media plays. In Nigeria, and indeed in much of Africa, there is a huge fascination with the West, especially with American culture. This is so powerful. America owns the minds of young people. So whatever they find fascinating with American culture, there is an attempt to replicate it. Whatever happens in American culture, it will affect everything. It will affect the way they dress. It will affect the way they talk, and the music they make.

What we actually should be thankful for is the fact that they have enough culture in them to even put some of their native traditional culture, like singing in Yoruba, singing in pidgin English, and using beats that are still reminiscent of the Nigerian groove. If you go to Nigeria today and put on the radio, it's only in the last five or six years or so that you start to hear more of this Nigerian so-called hip-hop or Afrobeats music. Before that, it would've been the latest r&b, the latest hip-hop, so in a way, it's still a good thing… I mean, you go to a party now, and you can be sure that the music will be driven by 80 percent Nigerian music. So it’s still some progress.

There are so many parallels to that. Congolese music, starting out, is imitating Cuban music, and then becoming its own thing. It's a very interesting process. Looking at the American thing, that has always been there. There's always been a fascination with America. Even Fela. He doesn't like it when people point out that his style was partly based on James Brown, but it's there.

It is apparent.

But, you know, it feels like now it's a little bit over the top. The influence is so strong.

But if you look at a person like Fela, what is unique is that he made the sound his own. Every creative musician is influenced by things he hears, but if you develop a voice of your own, then it will sound sufficiently unique to be different. But you only need to hear a few lines to hear that scratchy rhythm guitar of James Brown. Or you're going to hear the sensibilities of the singing style and everything. But the whole entity itself was uniquely different.

The younger folks are also making a difference with some of the beats, but it's a bit more difficult when everything is programmed. Part of what makes the huge diversity possible here in America is the fact that there are lots of musicians who are playing their instruments. So the computer and the keyboard midi-controller is not the only instrument. In juju, like in King Sunny Ade’s band, the guitars are more important than the keyboards. They are more the main instrument—all those riffs over each other, with all the talking drums, and all the riffing.

But when you come to Nigeria again and we’re able to take you to see some of the music you haven't heard. Some of this music is very popular. Hugely popular.

Sean: Traditional music?

Well, they came from traditional stuff. Some came from juju. There's one called tungba, which is very popular in the church, even though it's based on the drums of juju. Even sometimes now you will hear the music evoking King Sunny Ade played by tungba. They are talking with the drums, but they are playing rhythms, they are playing short rhythms with a very dance component so to speak. They also grew out of fuji. So there are many forms that are really quite vibrant and popular, and many of them are drum- and rhythm-driven.

Tungba. Or saje. Sometimes I even wonder, because I've tried to research the history of the word tungba--and I was thinking, I hope that it's not from the Latin American tumba. You never know. But you know, it is a powerful variant. It is still juju, but it is not that floating, bucking drum stuff. It's more like heavy rhythmic stuff.

Drums for me, and the rhythms, are underappreciated. If I see a lot of stuff from Western researchers around Mali, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Congo, I think the melodies and the harmonies have played a significant role in what fascinates them. But really, if you take away the vocals, and take away the harmonies and keyboards and stuff, and to just listen to the beats of Yoruba, it's incredible what is possible. That's the reason why I refuse to just sit still and say I do Afrobeat. I don't care to just make a quick buck and do what is very commercial and popular. Hey, Fela is very popular now, so let me ride on that. I have a huge image how people can combine your music with Fela, because of the stuff you talk about. But I don't care to ride on that.

Sean: That's my reaction to a lot of the new music. The rhythms are often so basic, and coming from a country with such a rich traditions. But who am I to tell? So coming back to the Afrobeat scene, there’s Femi and Seun. Is anyone else playing Afrobeat?

Those are the two most successful. And I would say the most serious and most committed of these musicians. There are several others. But they don't sound as good. Afrobeat is more complex to play than the quick Afrobeats with an “s” stuff. Because of the computer. You have to learn your instrument. You've got to understand some basics of orchestration and arranging. You've got to be able to play your horns in tune. It's not as easy.

The part that they found very easy to do are the basic shekere and the clave. But if you listen to the older Fela songs, Tony Allen's playing was not clichéd. And that's why until today it is unique. I have listened to him talk about it, and I wonder. Does he really know what he was doing? Can he really describe what he was doing? Or is he deliberately keeping the formula away?

All he was doing was playing those drums, not like Western kit, but using the rhythms that are Yoruba rhythms. So you would never hear a kick and snare prominently driving the music. Even in the mix, the kick and the snare would just be part of the mix, like other percussion instruments. In Western music, the kick and the snare are very prominent. So it's not just rhythm, it's also the levels of these components of the drums in the music. So if you listen to different songs, you will hear the rhythms are different. And you know, the times they're locking with the bass, which is also a standout Western-style thing, along with the kick. The drums and the bass. But still, since the bass is talking, the drums too are talking. So all these songs like “Nadine,” “Shakara,” “Question Jamosa,” “Zombie,” “Water No Get Enemy,” all these are different drum rhythms. It seems to me that after Tony Allen left, it was probably more difficult to find somebody who would understand the concept. So to keep some basic rhythms from the older repertoire, and brought them into the music.

If I were Fela, I would have just found a jazz drummer and sat him down for like three months of Yoruba music. Because jazz drummers are the ones that play with separate limbs. And you can make the drum kit sound like a little ensemble of drums. And not just revert quickly to kick, snare, kick, snare. Of course, Fela’s music was bigger than just Tony Allen. But there was that major role that the drums played there.

Sean: So are there young fuji and juju artists coming up?

Juju has metamorphosized more into the tungba and saje style beats. I would say this is the new juju. Sometimes they don't even call it juju. But the sensibilities are still juju sensibilities. Fuji also is still big. My theory is that part of fuji's survival is because it's inexpensive to put a fuji band together. Until now, that they brought in the keyboard and the guitar and the saxophone, it there was only drums before. Also, because of the history of the Islamic and Arabic influences, it will always be there. So Fuji and juju are still big.

Is it drawing young people, middle-aged people? All people?

All. All.

And do these groups come to play at your club, Motherland?

Not much anymore. Fuji itself is probably more people listening amongst the Yoruba. The older folks are still there. But there are lots of young folks who are playing.

I think there's an opportunity for someone to come up with a new young fuji group—not to bastardize it, but to some open the sound a bit so it can be received on the international stage.

I think so. I think it boils down to charisma and personality more than the music. Because a lot of what you have is a musician is your character, more than just your sound. If he has the right personality, the charisma, to make it interesting, it could happen. It could happen.

One last question about this term “Afrobeats.” It was coined in London, wasn't it? How long has it been common in Lagos?

I think it’s actually more online that I hear about Afrobeats. The real names I don't even know, they call it hip-hop. Even though it isn't really that, but it has more affinity with its source, which is hip-hop. But Afrobeats in the last year or so is the thing I'm reading about. The thing I'm glad about is that at least in some way, it brings some honor to Fela, who pioneered the concept of taking an African beat and making something new out of it.

That's a good way to look at it. Because when I first heard that word, I thought, oh my God, now they've confused everything. But I understand that if you look at the numbers, this music is selling. It is top-charting music in the U.K. It's having success that Fela’s Afrobeat never had. So in that way, you are right, it's good to bring recognition. Thank you,man. This has been great.

Thank you.