Simon Rentner recently spoke with Lamine Touré, Senegalese sabar player and Griot, to shed light on the drumming traditions that lead to mbalax and its popularity. Lamine gave great insight on bakk composition, being a Griot, his groundbreaking sabar player grandmother, and more.

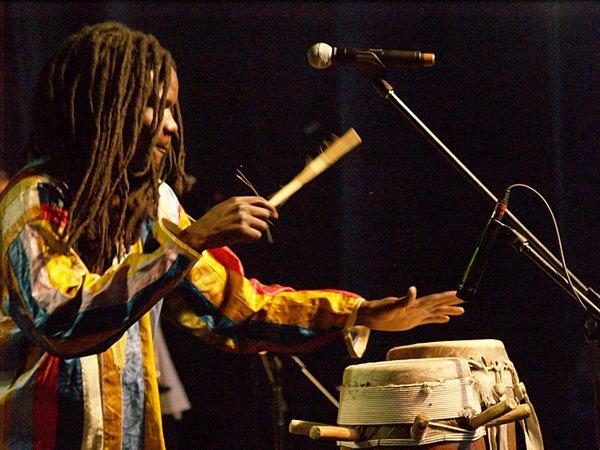

Simon Rentner: I'm here with Lamine Touré, Lamine please introduce yourself to our audience and what you play.

Lamine Touré: My name is Lamine Touré from Senegal, West Africa. I'm a sabar player. Sabar is an instrument from Senegal. I'm a Griot. I was born in a Griot family, a really big Griot family in Senegal, in Kaolack. My family are all drummers and dancers and singers.

S.R: You come from a strong family of women especially that are Griot - your grandmother in particular was essentially legendary. Can you talk about her a little bit?

L.T: Yeah. My father is not Griot but my mom's side was Griot. My grandma is Griot. She was really famous a long time ago. She danced well. She is a great dancer and singer. Yeah, she did a lot. One of my family - you know usually in Senegal women are not drumming, but when it's my family even the women drum. That's the reason I play sabar or sing or dance is because of her. I know she passed away before I was born, a long, long time ago but my grandma, everybody says a lot of good things about her and says how she was before.

S.R: So how old were you when you started hearing about your grandmother?

L.T: When I was four years old was when my mom gave me drums. She said, "Your grandma did the same thing with your brother." My oldest brother. My grandma used to make him small drums to play. But when I was born, at four years I started hearing my grandma's story and they did a lot for us too. They did a lot about the Griot. It was really hard in Senegal at that time for people to know you. But she did a lot of work for the family.

S.R: It must be a great source of pride for you, especially to have women that were actually playing the drums too. It's very progressive, right?

L.T: Yeah. Usually you wouldn't see it in Senegal. Women only dance in Senegal. Women usually are not playing drums. But in my family some of them danced and some of them played drums. Sometimes they played a lot. If they played a lot they needed a lot of different players. If they didn't have them, they could just hire my grandma's sister. My grandma's sister's name was Agida Seck. She used to drum a lot. Yes, she was a great drummer. Yeah.

S.R: I recently spoke with Toumani Diabaté. He said 73 generations was the number of generations his family had been Griots. Do you have an awareness that specific? Do you know how many generations you can count?

L.T: Yeah. My great-grandma, not my grandma, but my grandma's great-grandma, right? Is that how you say it? She used to talk to me. At the time I was maybe five, six years old. She was almost a hundred years. But she was really old. She was telling us what generation, how it went sabar style. It was a long, long time ago. She said a lot. When they started drumming and dancing, how many drums they had before. She would just say to us they used to only have one drum. Later on we had five. But before, at the beginning, they only had one. She would say drumming was the Griot form a long, long time ago. I don't know exactly. She didn't tell me how many hundred years ago but it was a long, long time ago. She learned it from her family. The family before her family, that's how they passed the message. They kept telling the new generation. She wanted us to make sure we knew too so today I can tell how long ago they used to dance, they used to drum. She'd tell it all usually when we'd eat lunch. We were all ten in the house or more than ten. She would give us food and start talking about this story before, about sabar, about dancing about Senegalese culture and what happened before, what it looked like before. But she explained a lot. I learned a lot about sabar, about the story about when sabar started, where sabar started. She even knew where sabar started. Joloff is in the middle of Senegal. It's named Joloff. Joloff - that's where they say Wolof started - the language. But she'd say a lot that sabar started over there. It was a good thing for me to learn and to know from her because she had more experience than I did. She was the oldest in the family. But she would tell a lot of stories about sabar, stories that did educate me. I have a lot of education about that because she made us stronger, saying this is what sabar did, this is what sabar started. Sabar was here hundreds of years ago and you have to keep it. Just play. Just keep playing. Keep the story.

L.T: Yeah. My great-grandma, not my grandma, but my grandma's great-grandma, right? Is that how you say it? She used to talk to me. At the time I was maybe five, six years old. She was almost a hundred years. But she was really old. She was telling us what generation, how it went sabar style. It was a long, long time ago. She said a lot. When they started drumming and dancing, how many drums they had before. She would just say to us they used to only have one drum. Later on we had five. But before, at the beginning, they only had one. She would say drumming was the Griot form a long, long time ago. I don't know exactly. She didn't tell me how many hundred years ago but it was a long, long time ago. She learned it from her family. The family before her family, that's how they passed the message. They kept telling the new generation. She wanted us to make sure we knew too so today I can tell how long ago they used to dance, they used to drum. She'd tell it all usually when we'd eat lunch. We were all ten in the house or more than ten. She would give us food and start talking about this story before, about sabar, about dancing about Senegalese culture and what happened before, what it looked like before. But she explained a lot. I learned a lot about sabar, about the story about when sabar started, where sabar started. She even knew where sabar started. Joloff is in the middle of Senegal. It's named Joloff. Joloff - that's where they say Wolof started - the language. But she'd say a lot that sabar started over there. It was a good thing for me to learn and to know from her because she had more experience than I did. She was the oldest in the family. But she would tell a lot of stories about sabar, stories that did educate me. I have a lot of education about that because she made us stronger, saying this is what sabar did, this is what sabar started. Sabar was here hundreds of years ago and you have to keep it. Just play. Just keep playing. Keep the story.

S.R: For you and for a lot of Griot musicians and percussionists, it seems like destiny. What is that like? I have no idea what I was born to do, but you know exactly what you were born to do.

L.T: Yeah, I know exactly what I was born to do because when I was born, I was born in a Griot family. When I started playing at four years I just said, "This is what I like." My grandma taught us a lot. Whatever you want for your life, if you like it you will succeed. You know, just believe in what you doing. This is born to your family, your grandma's family. If you keep going with this, you will succeed. Do you understand? Because in Senegal, even Griot families, some people say it's not a real job, just to drum. They think it's not a job. But when we were born, our family, we made it like this was our job. My grandma made us know we can do what we want with this. We don't have to keep it. I'd just keep playing every day, singing the songs. There are a lot of songs they created that helped me for my future. Those songs were kind of telling me, "You'll be strong." There are some songs they sing or they play on the drums but it did help me when I grew up. That helped me because it made me strong and believe in what I was doing. One day I'm going to be a musician in Senegal. I was just born to know this is what I'm going to do. I'm going to have what I want with this drum. Or I'm a Griot but I'm going to succeed with what I'm doing because they taught me that too.

S.R: But there has to be a brother in your family or a sister that just didn't get that musical gene; that just has no musical skills.

L.T: Yes, yes.

S.R: Now, how do they live their life knowing that they come from this family and they're supposed to be Griot, they're supposed to be a percussionist, but they just can't hear it.

L.T: Yeah, I know. One of my brothers, he is not a player at all. He doesn't like it. He liked it. When we were kids he liked to play. But the playing does not like him. Do you understand what I'm saying? I don't know but he liked to play like us. It was really easy for me to drum. Every time when I'd hear a phrase I would do it right away even though I was four years old. We would hear our uncle play a really long phrase but we would do it right away. We would learn it. I don't know why. My brother, he can't play. He tried. But he is not a player. I know if he were playing right now he might be happier now. Right now I know he has a life. But it's different. If he was playing it would help him more today. But he is a businessman. He's not a drummer.

Patricia Tang, Scholar: Can you maybe talk also about your older brother, Alassane Djigo? His older brother is significantly older. He was one of the percussionists for Super Diamono and he influenced Lamine a lot in terms of getting interested in playing for mbalax bands.

Patricia Tang, Scholar: Can you maybe talk also about your older brother, Alassane Djigo? His older brother is significantly older. He was one of the percussionists for Super Diamono and he influenced Lamine a lot in terms of getting interested in playing for mbalax bands.

L.T: My brother is a big musician in Senegal. He used to play with Super Diamono. They traveled everywhere. They traveled a lot. He was really famous in Senegal. I liked to play the music because of my uncle Aziz. I have my other uncle who was the first guy to bring sabar in the music in Senegal. That's him. He started it. Before the music in Senegal was salsa or they played congas. They never played sabar. It was Aziz, my uncle, who was the first guy in Senegal who put sabar in the music. I heard him playing when I was four. As he was playing I kind of imitated him playing on my stomach, what he did. But I liked music because of my uncle and my brother.

S.R: He was kind of like a founder. He was kind of like a pioneer then?

L.T: Yeah. Yes. Aziz, yes. Aziz - everybody knows him in Senegal. They give him a lot of respect because you have mbalax, Senegal's style of music, because of him. It was he who brought sabar and then played really crazily. He played. He changed it. He gave them some musical phrases. If I play this, the drum set play with me, he changed it. It was really amazing.

S.R: Is there a particular recorded performance with your uncle that you would like to share with all of our listeners that you just think was totally crazy or that you used to imitate all the time?

L.T: Yeah. Yeah, there are some songs I liked to imitate of his. We all liked our uncle because that was him who made us want to be musicians. Before we were only drumming. We didn't know what we were going to be. But when I heard him playing he made me want to be a musician, and my brother, Alassane, too. I have another uncle, Thio Mbaye, who is playing with Youssou N'Dour right now. He is a famous guy, too. He is the best. If you ask the best drummer in Senegal is, I'm going to say it's Thio Mbaye. He’s my uncle too. He is a great practitioner and he is playing well. He plays with a lot of different musicians.

S.R: He's with Rimbax.

L.T: Rimbax, yeah. That's Thio Mbaye. I played with him for a long time, when I moved to Dakar. And my other uncle plays for Baaba Maal. His name is Bada, Bada Seck. He is a really famous drummer too. He and Thio are the same age.

S.R: In one of his songs, Youssou N’Dour says, "Whatever you may have become, even if you have acquired social status, it's only right that one day you should return to your homeland." What do you think of that?

S.R: In one of his songs, Youssou N’Dour says, "Whatever you may have become, even if you have acquired social status, it's only right that one day you should return to your homeland." What do you think of that?

L.T: I believe that, yeah. You ask me, "You think you are going to go back to Senegal?" Me? Yeah. I'm going to go back. That's where I came from. I like my country. I like Senegal. That's where I lived most of my life, in Senegal. I go every year and I would like to help Senegal. I like to help build stuff, because it's a really nice country. I like it. It's a country I'm not going to ever, ever forget because that's how they educated me. I'm going to go back when I get old. Not right now, but when I get old I'd like to go back and bring my family too, if I had kids here. I want them to know Senegal. But myself, I'm going to go back. Yes.

S.R: You're from Kaolack?

L.T: I'm from Kaolack.

S.R: Kaolack has its own bakk, right?

L.T: Yeah. Yeah, Kaolack rhythm is the rhythm that changed the music, that turned it into mbalax. Before—a long, long time ago—Kaolack had a lot of different rhythms. They created a lot of sabar rhythms. The people from Kaolack play really well. They were the best players in Senegal. I’d say that. They created a lot. They have a lot of techniques. That's why when my uncle Aziz moved to Dakar, Diamono chose him. They had never seen any player in Dakar like him.

S.R: So he is from Kaolack too?

L.T: Yeah. He was born in Kaolack. He moved to Dakar when he was grown, trying to play there and find a job. When Super Diamono saw him, they said, "Wow. We’ve never see anyone who is playing like you." He can play five drums at the same time. He had a lot of experience. He created a lot. But that's why mbalax came from Kaolack. Mbalax is like the Kaolack rhythm. We have a rhythm that's named Kaolack. In Senegal, people dance a lot to the Kaolack rhythm--they like the Kaolack rhythm. In the music right now, if you see the way they play in the music, it came from Kaolack.

S.R: What are some of your all-time favorite bakks? There are so many. But if you are going to choose three?

L.T: I can choose one. I have one bakk from my family. This bakk is maybe 200 years old. It's long. [Sings.] It's a long bakk. It's really long. But that bakk, I like it because it has the phrase - the bakk is really old. It's more than 200 years old but it has a lot of technique in it. If you are a sabar player, when I play the bakk I'm going to say, "Wow. How did my family create this bakk?" Because we think sabar advanced a long, long time ago. I see how they communicated, how they played, the technique. They used to play that phrase, that bakk. It's amazing. That's why I like that bakk. Right now, that bakk is really famous. Even though it's 200 years old we still play it now.

S.R: In Patricia's book, you say that because she is learning the bakks that you are teaching her.

L.T: Yeah.

S.R: And she is, I would assume, playing them well enough that you say she is a Griot too.

L.T: Oh, yeah.

S.R: Would your whole family agree with that statement? Would your whole family think that she is a Griot?

L.T: Yeah. My family says it because we have a lot of people who are in the family. If you like sabar and you are learning and you are drumming we are going to call you Griot. Yes. She is a Griot. Yeah, because my family agrees too. It's a different life.

S.R: There's this contradiction too, because also in the conclusion of the book you say, one of the more definitive statements is, "It's along blood lines and that is very important."

L.T: Yeah.

S.R: So what is this idea of blood then?

L.T: Yeah, the bloodline is really important. But in Senegal, we have a lot of people who are not our blood family but they play really well. Their families are a different ethnic group but they come and learn sabar with our family. They are from Senegal. But they are not like a Griot family. A long, long time ago, if you are not a Griot, it is a problem. You are not a Griot, if you're not of the same blood, for them you don't have the right to play. But right now it's different. I'm talking about a long time ago. It's not about the Griot family who says you don't have a right to play. But there are a lot of people in my family - my grandma, my grandfather, a lot of his players were not Griot. He taught them. He taught them how to play. They played really well. They considered them Griot. They married in the family. Right now even though they didn't come from a Griot family, when they play, they play well. They play. We say they are Griot.

S.R: Was there a sense of optimism in the air about the direction of the country when mbalax was invented?

S.R: Was there a sense of optimism in the air about the direction of the country when mbalax was invented?

L.T: Yeah. The people were really happy about the direction we were going with mbalax, right? People were really happy because mbalax, the music, came from Senegal. It's not something we copied, not like we took the salsa music or jazz. Mbalax is some music that came from Senegal, the rhythm. It came from the sabar. The Griot family created that. That's why we are proud of having that kind of style of music in Senegal. That's why everybody likes it. Even if you go to a club, that time when they start, if you don't play mbalax, that means you're not going to advance. Nobody is going to listen to you. We finally say, "Oh, this is art." Everybody likes mbalax. Everybody feels it. It's kind of like here, if you play rock music or hip hop, everybody knows. In Senegal, it's the same. When they created mbalax, when mbalax style started, everybody liked it because it was our music. It came from Senegal.

S.R: Do you have a sense of pride too, that it has become one of the main cultural exports from Africa? Especially of all the other genres of African music, it's perhaps the biggest.

L.T: Yeah, mbalax is really big. One day, everybody started to love it in West Africa. If you go to Gambia, they listen to mbalax a lot because it's from Senegal. If you go to Mauritania, if you go to Mali, they all like it, Côte d'Ivoire, they like mbalax. All over West Africa they know mbalax well. They like the style, the way we dance because it's different. You're not going to see that in a different country. It's only in Senegal you're going to see mbalax music. If you go to a lot of different countries in Africa they have soukous. It's almost similar. Each country has the same music. In Senegal it's mbalax. It's only - if you want to hear Mbalax music, it's only Senegal who is playing that kind of music. But in West Africa they are all proud of mbalax. They like it too. It's making people - it seems like it is really, really big right now even in Europe. In Europe they like it. Not in the United States.