Blog June 28, 2013

Lebanon Journal 3: Cosmopolitan Beirut

On a Wednesday night in Beirut’s bustling Hamra district, the pubs are pumping out classic rock and DJ dance grooves while a slow stream of traffic provides a shifting counterpoint of percussive horn honks, throbbing bass lines, and here and there, elegant strains of Arab art music—violins, frame drums, oud and qanun, the iconic voice of Lebanon’s maternal diva, Fairuz. People strolling the sidewalks past fashionable clothing stores and restaurants, and Starbucks, also run a wide gamut. Plenty of swarthy young men sport tight jerseys, super short haircuts, and carefully half-grown beards. Young women might wear loose frocks and tight jeans, or cotton dresses—somehow dressy and informal at the same time—freely. They also might wear colorful robes and veils, or some combination of the two looks. We’re near the American University of Beirut, so youth prevails. But there are plenty of older folks out strolling too, gentlemen with sun-cured, deeply lined faces in pressed trousers and button-down short sleeves, and women in traditional dress, full length robes with sequins and matching veils, not covering faces, but projecting reserve and dignity.

Along the way, I pass escapees from the Syrian conflict that surrounds tiny Lebanon on two sides, and, many fear, threatens to engulf it. The most visible refugees are women, veiled, wearing black, seated on the sidewalk and begging mournfully. Sometimes it’s just a woman and a child; other times it might be a tight circle of women, huddled together in their misery. Outside Hamra’s trendy Metro el Medina nightclub, one such circle of grief is convened mere yards from an open space where local boys are showing off their version of b-boy moves on polished stone pavement.

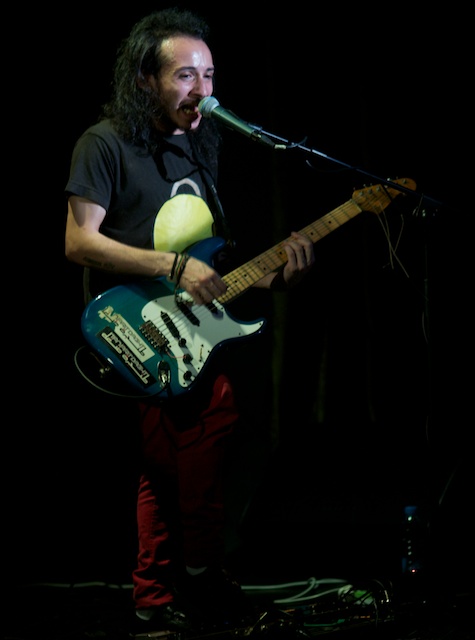

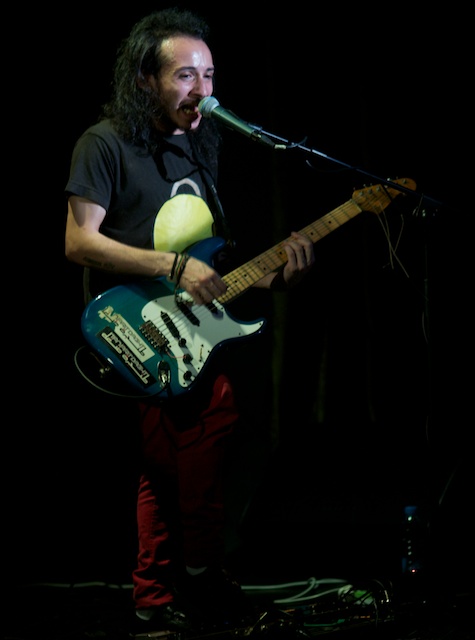

[caption id="attachment_11127" align="aligncenter" width="475"] Guitarist/singer for Tanjaret Daghet (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Inside the club, a different echo of the Syrian conflict is unfolding. It’s the debut CD release party for a three-piece rock band called Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Pot), which has been making waves in Beirut’s small but active alternative music scene during some 18 months in exile from their home in Damascus. The band is tight and strong, a nuanced power trio featuring a diminutive, long-haired guitarist, a bass man with a kind of Arab-Mohawk haircut, and a superb drummer with a powerful, airy attack. The music might reference Pink Floyd here, Nirvana there, and The Police elsewhere, but the Arab-language vocals are distinctive—floating dreamily, spitting panic or howling rage. And the trio’s turn-on-a-dime rhythm changes are arresting, and carried out with easy precision. The total effect is decidedly original, a sterling example of Arab rock. The crowd, most of whom understand the band’s topical lyrics are quickly in a swoon, bobbing, shouting, and whistling approval. There’s an intensity I had not heard in Beirut’s own rock acts, but then, in two weeks, I have barely scratched the surface. This city is deep, and full of surprises.

[caption id="attachment_11116" align="aligncenter" width="454"]

Guitarist/singer for Tanjaret Daghet (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Inside the club, a different echo of the Syrian conflict is unfolding. It’s the debut CD release party for a three-piece rock band called Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Pot), which has been making waves in Beirut’s small but active alternative music scene during some 18 months in exile from their home in Damascus. The band is tight and strong, a nuanced power trio featuring a diminutive, long-haired guitarist, a bass man with a kind of Arab-Mohawk haircut, and a superb drummer with a powerful, airy attack. The music might reference Pink Floyd here, Nirvana there, and The Police elsewhere, but the Arab-language vocals are distinctive—floating dreamily, spitting panic or howling rage. And the trio’s turn-on-a-dime rhythm changes are arresting, and carried out with easy precision. The total effect is decidedly original, a sterling example of Arab rock. The crowd, most of whom understand the band’s topical lyrics are quickly in a swoon, bobbing, shouting, and whistling approval. There’s an intensity I had not heard in Beirut’s own rock acts, but then, in two weeks, I have barely scratched the surface. This city is deep, and full of surprises.

[caption id="attachment_11116" align="aligncenter" width="454"] Yusif at Purely Oriental, Metro el Medina (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For instance, a few nights earlier at this same club, I attended an evening of belly dancing called Purely Oriental. Off the bat this was a striking contrast to the desultory display of belly dancing Sean Barlow and I witnessed two years ago in Cairo. There, the art is moving steadily to the margins, no longer a staple at weddings, and mostly something aimed at another disappearing demographic in Egypt: tourists. But at Beirut’s Metro el Medina, the crowd was fulsome, local, and totally pumped. What’s more, two of the four dancers were men, a rarity. One of those men, I was told by a regular, grew up in a conservative Muslim (Hezbollah) milieu. He started dancing in his village at 16, but when it became known he was gay, he was forced out and came to Beirut to start a new cosmopolitan life as the dancer Yusif. Yusif is now married to a gentleman in Spain and was just in town for a visit, hence the excitement among the gathered fans at this performance, which was, I must say, the most entertaining belly dance performance I’ve ever seen.

Yusif at Purely Oriental, Metro el Medina (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For instance, a few nights earlier at this same club, I attended an evening of belly dancing called Purely Oriental. Off the bat this was a striking contrast to the desultory display of belly dancing Sean Barlow and I witnessed two years ago in Cairo. There, the art is moving steadily to the margins, no longer a staple at weddings, and mostly something aimed at another disappearing demographic in Egypt: tourists. But at Beirut’s Metro el Medina, the crowd was fulsome, local, and totally pumped. What’s more, two of the four dancers were men, a rarity. One of those men, I was told by a regular, grew up in a conservative Muslim (Hezbollah) milieu. He started dancing in his village at 16, but when it became known he was gay, he was forced out and came to Beirut to start a new cosmopolitan life as the dancer Yusif. Yusif is now married to a gentleman in Spain and was just in town for a visit, hence the excitement among the gathered fans at this performance, which was, I must say, the most entertaining belly dance performance I’ve ever seen.

No one would call Lebanon a beacon of social liberalism. Indeed an ongoing debate about “civil marriages” here is about whether people from different religious sects should be allowed to marry without one of them having to convert. So don’t hold your breath on prospects for gay marriage. But, in another sign of the fractured cosmopolitanism of Beirut, one of the city’s most successful rock bands, Mashrou Leila, has an openly gay front man—Hamed Sinno, whom we will hear from in an upcoming program—and that has not prevented the band from becoming one of the most in-demand live acts for young audiences, not just in Beirut, but in connected alternative communities in Cairo, Aman, Tunis, and, of course, Europe.

Lebanon’s particular brand of cosmopolitanism is largely determined by geography and history. Its mountainous north-south spine is fringed with so many steep valleys as to create remarkable degrees of remoteness and isolation within a very small territory. Lebanon’s strategic location at the junction of Arabia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia has subjected it to a dizzying succession of incursions, partitions, languages, religions, conflicts, and truces, all of which have left the nation’s very identity in a fragile state of constant re-negotiation—felt in the halls of its fractured government, the streets of its cities, towns, and villages, the airwaves of its multifarious radio and television stations, and anywhere where music is played.

[caption id="attachment_11112" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

No one would call Lebanon a beacon of social liberalism. Indeed an ongoing debate about “civil marriages” here is about whether people from different religious sects should be allowed to marry without one of them having to convert. So don’t hold your breath on prospects for gay marriage. But, in another sign of the fractured cosmopolitanism of Beirut, one of the city’s most successful rock bands, Mashrou Leila, has an openly gay front man—Hamed Sinno, whom we will hear from in an upcoming program—and that has not prevented the band from becoming one of the most in-demand live acts for young audiences, not just in Beirut, but in connected alternative communities in Cairo, Aman, Tunis, and, of course, Europe.

Lebanon’s particular brand of cosmopolitanism is largely determined by geography and history. Its mountainous north-south spine is fringed with so many steep valleys as to create remarkable degrees of remoteness and isolation within a very small territory. Lebanon’s strategic location at the junction of Arabia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia has subjected it to a dizzying succession of incursions, partitions, languages, religions, conflicts, and truces, all of which have left the nation’s very identity in a fragile state of constant re-negotiation—felt in the halls of its fractured government, the streets of its cities, towns, and villages, the airwaves of its multifarious radio and television stations, and anywhere where music is played.

[caption id="attachment_11112" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Curtain call for Silk Road program at Beiteddine (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

On June 21, I attended the opening night of the Beiteddine Art Festival, held at the entrance of an awesome Ottoman-era palace in the Chouf Mountains. That night, as the Lebanese Army was gearing up for an assault on a Salafist (Islamist) preacher in Sidon (just 20 miles, and a few of those steep valleys to the south), the stage at Beiteddine overflowed with musicians and dancers from places like Iran, Khazakstan, Syria, Mongolia and India. “In the Steps of Marco Polo: A Musical Journey on the Silk Road” lived up to Beiteddine’s reputation for impeccable grandiosity and breathtaking production. The narration by Rafiq Ali Ahmed in the role of Marco Polo struck some listeners—everyone is a critic here—as a theatrical contrivance used to thread together an essentially musical program. And intriguing liberties were taken. An anachronistic reference to 20th century Lebanese literary icon Khalil Gibran became an entrée to the inclusion of some splendid Lebanese music, notably by oud maestro Charbel Rouhana and one of the most celebrated young female vocalists around today, Abir Nehme (also interviewed for an upcoming program).

But if including Lebanon in the Silk Road is an act of whimsical invention, so be it. It seems that most if not all of the prevailing cultural and political narratives here are open to question. And as I leave Beirut after two weeks of music and conversation, I am left with more questions than answers, and a healthy respect for the task I will face in shaping this jagged, fractured cultural landscape into coherent radio narratives in the months to come.

Wish me luck…

Curtain call for Silk Road program at Beiteddine (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

On June 21, I attended the opening night of the Beiteddine Art Festival, held at the entrance of an awesome Ottoman-era palace in the Chouf Mountains. That night, as the Lebanese Army was gearing up for an assault on a Salafist (Islamist) preacher in Sidon (just 20 miles, and a few of those steep valleys to the south), the stage at Beiteddine overflowed with musicians and dancers from places like Iran, Khazakstan, Syria, Mongolia and India. “In the Steps of Marco Polo: A Musical Journey on the Silk Road” lived up to Beiteddine’s reputation for impeccable grandiosity and breathtaking production. The narration by Rafiq Ali Ahmed in the role of Marco Polo struck some listeners—everyone is a critic here—as a theatrical contrivance used to thread together an essentially musical program. And intriguing liberties were taken. An anachronistic reference to 20th century Lebanese literary icon Khalil Gibran became an entrée to the inclusion of some splendid Lebanese music, notably by oud maestro Charbel Rouhana and one of the most celebrated young female vocalists around today, Abir Nehme (also interviewed for an upcoming program).

But if including Lebanon in the Silk Road is an act of whimsical invention, so be it. It seems that most if not all of the prevailing cultural and political narratives here are open to question. And as I leave Beirut after two weeks of music and conversation, I am left with more questions than answers, and a healthy respect for the task I will face in shaping this jagged, fractured cultural landscape into coherent radio narratives in the months to come.

Wish me luck…

Guitarist/singer for Tanjaret Daghet (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Inside the club, a different echo of the Syrian conflict is unfolding. It’s the debut CD release party for a three-piece rock band called Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Pot), which has been making waves in Beirut’s small but active alternative music scene during some 18 months in exile from their home in Damascus. The band is tight and strong, a nuanced power trio featuring a diminutive, long-haired guitarist, a bass man with a kind of Arab-Mohawk haircut, and a superb drummer with a powerful, airy attack. The music might reference Pink Floyd here, Nirvana there, and The Police elsewhere, but the Arab-language vocals are distinctive—floating dreamily, spitting panic or howling rage. And the trio’s turn-on-a-dime rhythm changes are arresting, and carried out with easy precision. The total effect is decidedly original, a sterling example of Arab rock. The crowd, most of whom understand the band’s topical lyrics are quickly in a swoon, bobbing, shouting, and whistling approval. There’s an intensity I had not heard in Beirut’s own rock acts, but then, in two weeks, I have barely scratched the surface. This city is deep, and full of surprises.

[caption id="attachment_11116" align="aligncenter" width="454"]

Guitarist/singer for Tanjaret Daghet (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

Inside the club, a different echo of the Syrian conflict is unfolding. It’s the debut CD release party for a three-piece rock band called Tanjaret Daghet (Pressure Pot), which has been making waves in Beirut’s small but active alternative music scene during some 18 months in exile from their home in Damascus. The band is tight and strong, a nuanced power trio featuring a diminutive, long-haired guitarist, a bass man with a kind of Arab-Mohawk haircut, and a superb drummer with a powerful, airy attack. The music might reference Pink Floyd here, Nirvana there, and The Police elsewhere, but the Arab-language vocals are distinctive—floating dreamily, spitting panic or howling rage. And the trio’s turn-on-a-dime rhythm changes are arresting, and carried out with easy precision. The total effect is decidedly original, a sterling example of Arab rock. The crowd, most of whom understand the band’s topical lyrics are quickly in a swoon, bobbing, shouting, and whistling approval. There’s an intensity I had not heard in Beirut’s own rock acts, but then, in two weeks, I have barely scratched the surface. This city is deep, and full of surprises.

[caption id="attachment_11116" align="aligncenter" width="454"] Yusif at Purely Oriental, Metro el Medina (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For instance, a few nights earlier at this same club, I attended an evening of belly dancing called Purely Oriental. Off the bat this was a striking contrast to the desultory display of belly dancing Sean Barlow and I witnessed two years ago in Cairo. There, the art is moving steadily to the margins, no longer a staple at weddings, and mostly something aimed at another disappearing demographic in Egypt: tourists. But at Beirut’s Metro el Medina, the crowd was fulsome, local, and totally pumped. What’s more, two of the four dancers were men, a rarity. One of those men, I was told by a regular, grew up in a conservative Muslim (Hezbollah) milieu. He started dancing in his village at 16, but when it became known he was gay, he was forced out and came to Beirut to start a new cosmopolitan life as the dancer Yusif. Yusif is now married to a gentleman in Spain and was just in town for a visit, hence the excitement among the gathered fans at this performance, which was, I must say, the most entertaining belly dance performance I’ve ever seen.

Yusif at Purely Oriental, Metro el Medina (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

For instance, a few nights earlier at this same club, I attended an evening of belly dancing called Purely Oriental. Off the bat this was a striking contrast to the desultory display of belly dancing Sean Barlow and I witnessed two years ago in Cairo. There, the art is moving steadily to the margins, no longer a staple at weddings, and mostly something aimed at another disappearing demographic in Egypt: tourists. But at Beirut’s Metro el Medina, the crowd was fulsome, local, and totally pumped. What’s more, two of the four dancers were men, a rarity. One of those men, I was told by a regular, grew up in a conservative Muslim (Hezbollah) milieu. He started dancing in his village at 16, but when it became known he was gay, he was forced out and came to Beirut to start a new cosmopolitan life as the dancer Yusif. Yusif is now married to a gentleman in Spain and was just in town for a visit, hence the excitement among the gathered fans at this performance, which was, I must say, the most entertaining belly dance performance I’ve ever seen.

No one would call Lebanon a beacon of social liberalism. Indeed an ongoing debate about “civil marriages” here is about whether people from different religious sects should be allowed to marry without one of them having to convert. So don’t hold your breath on prospects for gay marriage. But, in another sign of the fractured cosmopolitanism of Beirut, one of the city’s most successful rock bands, Mashrou Leila, has an openly gay front man—Hamed Sinno, whom we will hear from in an upcoming program—and that has not prevented the band from becoming one of the most in-demand live acts for young audiences, not just in Beirut, but in connected alternative communities in Cairo, Aman, Tunis, and, of course, Europe.

Lebanon’s particular brand of cosmopolitanism is largely determined by geography and history. Its mountainous north-south spine is fringed with so many steep valleys as to create remarkable degrees of remoteness and isolation within a very small territory. Lebanon’s strategic location at the junction of Arabia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia has subjected it to a dizzying succession of incursions, partitions, languages, religions, conflicts, and truces, all of which have left the nation’s very identity in a fragile state of constant re-negotiation—felt in the halls of its fractured government, the streets of its cities, towns, and villages, the airwaves of its multifarious radio and television stations, and anywhere where music is played.

[caption id="attachment_11112" align="aligncenter" width="640"]

No one would call Lebanon a beacon of social liberalism. Indeed an ongoing debate about “civil marriages” here is about whether people from different religious sects should be allowed to marry without one of them having to convert. So don’t hold your breath on prospects for gay marriage. But, in another sign of the fractured cosmopolitanism of Beirut, one of the city’s most successful rock bands, Mashrou Leila, has an openly gay front man—Hamed Sinno, whom we will hear from in an upcoming program—and that has not prevented the band from becoming one of the most in-demand live acts for young audiences, not just in Beirut, but in connected alternative communities in Cairo, Aman, Tunis, and, of course, Europe.

Lebanon’s particular brand of cosmopolitanism is largely determined by geography and history. Its mountainous north-south spine is fringed with so many steep valleys as to create remarkable degrees of remoteness and isolation within a very small territory. Lebanon’s strategic location at the junction of Arabia, the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia has subjected it to a dizzying succession of incursions, partitions, languages, religions, conflicts, and truces, all of which have left the nation’s very identity in a fragile state of constant re-negotiation—felt in the halls of its fractured government, the streets of its cities, towns, and villages, the airwaves of its multifarious radio and television stations, and anywhere where music is played.

[caption id="attachment_11112" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Curtain call for Silk Road program at Beiteddine (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

On June 21, I attended the opening night of the Beiteddine Art Festival, held at the entrance of an awesome Ottoman-era palace in the Chouf Mountains. That night, as the Lebanese Army was gearing up for an assault on a Salafist (Islamist) preacher in Sidon (just 20 miles, and a few of those steep valleys to the south), the stage at Beiteddine overflowed with musicians and dancers from places like Iran, Khazakstan, Syria, Mongolia and India. “In the Steps of Marco Polo: A Musical Journey on the Silk Road” lived up to Beiteddine’s reputation for impeccable grandiosity and breathtaking production. The narration by Rafiq Ali Ahmed in the role of Marco Polo struck some listeners—everyone is a critic here—as a theatrical contrivance used to thread together an essentially musical program. And intriguing liberties were taken. An anachronistic reference to 20th century Lebanese literary icon Khalil Gibran became an entrée to the inclusion of some splendid Lebanese music, notably by oud maestro Charbel Rouhana and one of the most celebrated young female vocalists around today, Abir Nehme (also interviewed for an upcoming program).

But if including Lebanon in the Silk Road is an act of whimsical invention, so be it. It seems that most if not all of the prevailing cultural and political narratives here are open to question. And as I leave Beirut after two weeks of music and conversation, I am left with more questions than answers, and a healthy respect for the task I will face in shaping this jagged, fractured cultural landscape into coherent radio narratives in the months to come.

Wish me luck…

Curtain call for Silk Road program at Beiteddine (Eyre 2013)[/caption]

On June 21, I attended the opening night of the Beiteddine Art Festival, held at the entrance of an awesome Ottoman-era palace in the Chouf Mountains. That night, as the Lebanese Army was gearing up for an assault on a Salafist (Islamist) preacher in Sidon (just 20 miles, and a few of those steep valleys to the south), the stage at Beiteddine overflowed with musicians and dancers from places like Iran, Khazakstan, Syria, Mongolia and India. “In the Steps of Marco Polo: A Musical Journey on the Silk Road” lived up to Beiteddine’s reputation for impeccable grandiosity and breathtaking production. The narration by Rafiq Ali Ahmed in the role of Marco Polo struck some listeners—everyone is a critic here—as a theatrical contrivance used to thread together an essentially musical program. And intriguing liberties were taken. An anachronistic reference to 20th century Lebanese literary icon Khalil Gibran became an entrée to the inclusion of some splendid Lebanese music, notably by oud maestro Charbel Rouhana and one of the most celebrated young female vocalists around today, Abir Nehme (also interviewed for an upcoming program).

But if including Lebanon in the Silk Road is an act of whimsical invention, so be it. It seems that most if not all of the prevailing cultural and political narratives here are open to question. And as I leave Beirut after two weeks of music and conversation, I am left with more questions than answers, and a healthy respect for the task I will face in shaping this jagged, fractured cultural landscape into coherent radio narratives in the months to come.

Wish me luck…