Reviews December 28, 2012

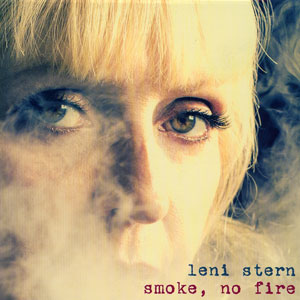

Smoke, No Fire

New York based guitarist and singer/songwriter Leni Stern has spent years making musical pilgrimages to West Africa, especially Mali, and bringing back intriguing recordings of her songs, played with amazing traditional musicians she has befriended. And beguiled, with her soft, clear singing voice, sweet and stinging electric guitar playing and gentle wit. This new collection was completed in Mali this year, just as the political situation in Bamako was being transformed in the midst of a coup and a rebellion to the north. The poignant title song here—which speaks of curfews and fear, and features a young man rapping in Bambara—only hints at the darkness that emerged in Mali last spring. It now appears that the wonderful Bamako ambiance Mali music adventurers like Stern—and, I dare say, myself—have savored for decades, has been swept away for the foreseeable future.

But back to music. Stern has become adept and interweaving English and Bambara vocals in her vocals. So when the her English verse shifts to a choral Bambara refrain, we barely notice, lost as we are in an ambling, wassoulou-tinged groove of the opener, “Djarabi (My Love)”—not the Mande classic, Stern’s own song. The core of this album is a well-developed musical friendship between Stern and Harouna Samake, whose sterling kamele n’goni (young man’s harp) has graced recordings and performances by wassoulou diva Sali Sidibe, and, more recently, Mali music icon Salif Keita. Stern and Samake have a sound. It can be deep and discursive, as on “Yiribi (tall tree)” with its rubato intro revealing a hint of a growl in Stern’s songbird voice. It can be lyrical and grooving as on the instrumental “Tou Samake,” on which we hear Samake’s remarkable command of his instrument—he is about the best I’ve heard—more clearly than on any Malian recording so far.

This is a seductive set of songs. On the chugging “Lomeko (Find me an angel),” men do most of the singing in a folksy ensemble sound that sets up an unusually jazzy and technical guitar solo. The feeling is playful, jazz rubbing up against African folk like old friends. On “Dji Lama (water),” Stern raps and riffs before singing sultrily in a minor key. A female chorus coils around another Stern/Samake groove, this one like an undulating waltz. Samake’s solo here is short, but sublime. The set ends on a folksy note with another instrumental, “Frossira (Country Road)” in which a violin hovers as Stern’s guitar tangles with Samake’s kamele n’ngoni, which shifts between rhythmic snap and melodious flourish. This ambling multi-cultural tumble feels like the old Bamako, a place of easy exchanges and chance-taking. And it leaves one with a sense of hope that is truly welcome, even if unwarranted.