The Niger-based quartet Les Filles de Illighadad is wrapping up the U.S. leg of an international tour in April, 2022. Fatou Seidi Ghali, Alamnou Akrouni, Amaria Mamadalher and Abdoulaye Madassane—three young women and a young man—perform entrancing Tuareg songs with an emphasis on beautiful, buzzing vocals that, after awhile, settle deep into one’s subconscious, with the power to hypnotize.

I caught them in Boston at a Global Arts Live presentation in the elegant new Crystal Ballroom at the Somerville Theatre. Before the show, I had a chance to sit down with the three women and learn more about their remarkable story. Unfortunately, our only shared language was French, and none of the three had even as strong grasp of the tongue as I do. A Tamashek translator would have made all the difference, but as it was, we did the best we could, and I managed to learn a few things.

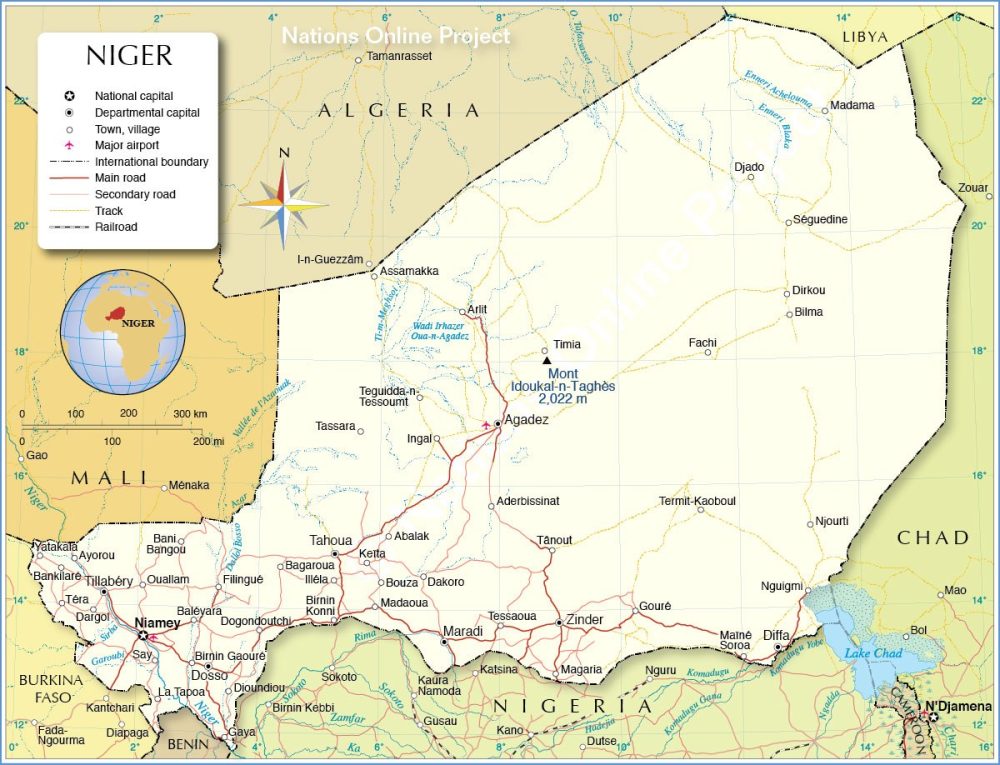

Ghali and Akrouni grew up in a small village 47 k.m. from Abalak in the region of Tahoua in southwest Niger. Beyond houses and a school, there’s not much there, and it is extremely remote, dependent on men to travel long distances to find water for the animals, and to take back to the village. The other two musicians come from the Agadez region. “But,” said Mamadalher, “we are all in the same family because we are all Tuareg.” The group formed in 2014, with the encouragement and guidance of Christopher Kirkley of the desert-focused label Sahel Sounds.

Ghali is the central figure, playing deft guitar and mostly singing at stage center. As is so often the case with African guitarists, she picked up the skill on her own, with little encouragement. “It was actually a close friend of my brother’s who came from Libya with an acoustic guitar,” she told me. “So then my brother started trying to play guitar, but he couldn’t really do it. So when he left the guitar, I took it when he wasn’t around. I started playing in the takamba rhythm. My brother warned me that Tuareg women did not play guitar, so I would play when no one could hear me. I didn’t want anyone to see me playing guitar because it is very rare that you see a Tuareg woman playing guitar. Women play tehardent [spike lute, used in takamba music], and imzad [traditional fiddle], and tende drum, but not guitar.”

Apparently, it was the arrival of Kirkley in 2014 in their village that turned things around. “He was looking for female musicians,” said Ghali. “He wanted to make some recordings, some videos. And he wanted to arrange a tour as well. Now, we could see a future. Our religion, Islam, did not want people to play guitar, even men. But it is more accepted now. At our weddings and baptisms, it is the men who play. A woman might be invited to play one or two songs, but she will be ashamed to play in front of people. This was an obstacle.”

In 2016, they released their self-titled debut album, followed by Eghasss Malan in 2017, and Les Filles de Illighadad at Pioneer Works, a live recording made in Brooklyn before the pandemic and released in 2021. Listening to any of these albums reveals the unique place this ensemble holds in the ever-growing ranks of “desert blues” releases, even the sub-category of Tuareg music. Start with the dominance of female voices. These three singers have perfected a unison choral sound that keens and vibrates, a true siren song of the desert. The accompaniment is spare, rooted in the pounding heartbeat of a calabash water drum. The guitar work is gentle and melodious, never flashy. But the cumulative effect hits the spot for lovers of trance music.

Fatou told me that their repertoire consists of traditional songs, old songs, not their own compositions. When I suggested that their sound was a mix of the folkloric sound of a group like Tartit and the desert rock of groups like Tinariwen, they pushed back. It’s not a mix, they said. There are two separate repertoires: tende songs led by the drum, and guitar songs—different things. “For the tende,” said Akrouni, songs talk about camels, villagers, fruits, the pasturing of animals, daily life and also brave Tuareg men who do great things for the village, like leading long voyages with the camels.” Akrouni is the principle tende player and singer. She explained that the drum is made with goat skin and played with bare hands.

The guitar songs are another thing altogether: love songs. “The guitar is something new,” said Fatou. “It is not part of our tradition.” Amaria explained that when you watch the group you can tell the two repertoires apart by who is singing. On the guitar songs, the tende and calabash accompany the guitarist/singer. On the tende songs, the guitar fades into the background and the tende player sings. “The calabash is always there,” she adds. The calabash this group uses is placed round-side-up in a tub of water, and when it is struck with vigor, particularly when Alamnou wields the beater, water splashes out around the edges, adding to the joyous atmosphere.

I asked how the musicians had adjusted to the life of international touring, having lived in the remote Sahara all their lives. My question evoked peals of laughter from all three women amid which it was difficult to get details. But the answer seemed to be that, at first, everything was autre choses, new stuff—airplanes, cars, even the food. But now, after a few tours, they more or less know what to expect. Places have become familiar. Shared girlish laughter seems to be characteristic of their touring life. I had the sense that these women keep a close eye on each other and share myriad inside jokes among themselves, another charming aspect of their friendly, folksy appeal.

(All photos by Banning Eyre)

Related Audio Programs