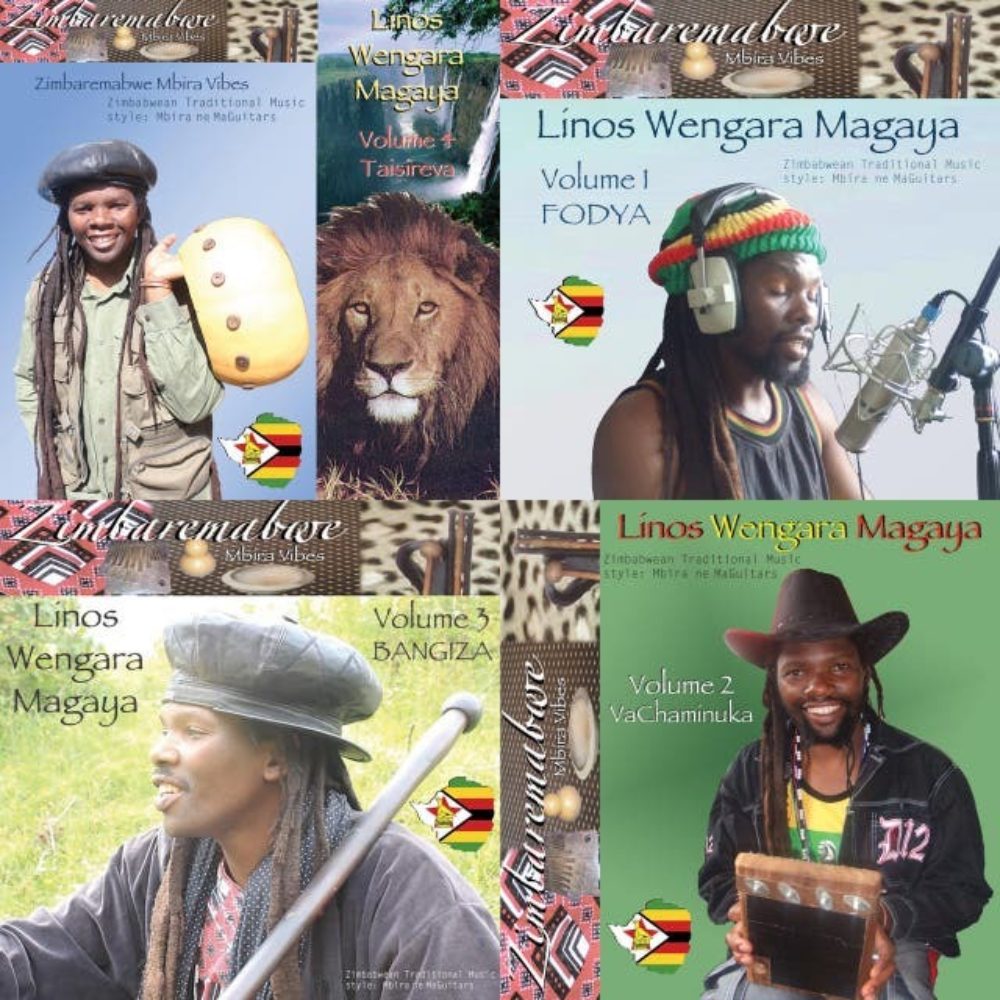

Linos Wengara Magaya is a U.K.-based Zimbabwean musician and bandleader, getting ready for his first visit to the United States in summer 2020 (assuming we’re open for business by then!). Magaya was raised in traditional culture and his music is based in the healing culture of Shona mbira music. His band, Zimbaremabwe, covers a variety of styles, but specializes in the chimurenga style of electric mbira music pioneered by Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited. Magaya and his musicians believe that this uniquely Zimbabwean genre needs new young artists to carry it forward, and on the band’s new album, Mwarirwe, they show themselves up to the challenge. Banning Eyre reached Magaya at his home in Brighton for an in-depth talk about his music and plans to visit the U.S. Here’s their conversation.

Since this is the first time we've spoken, let’s go back to the beginning. Tell me your story, where you grew up, how you became a musician.

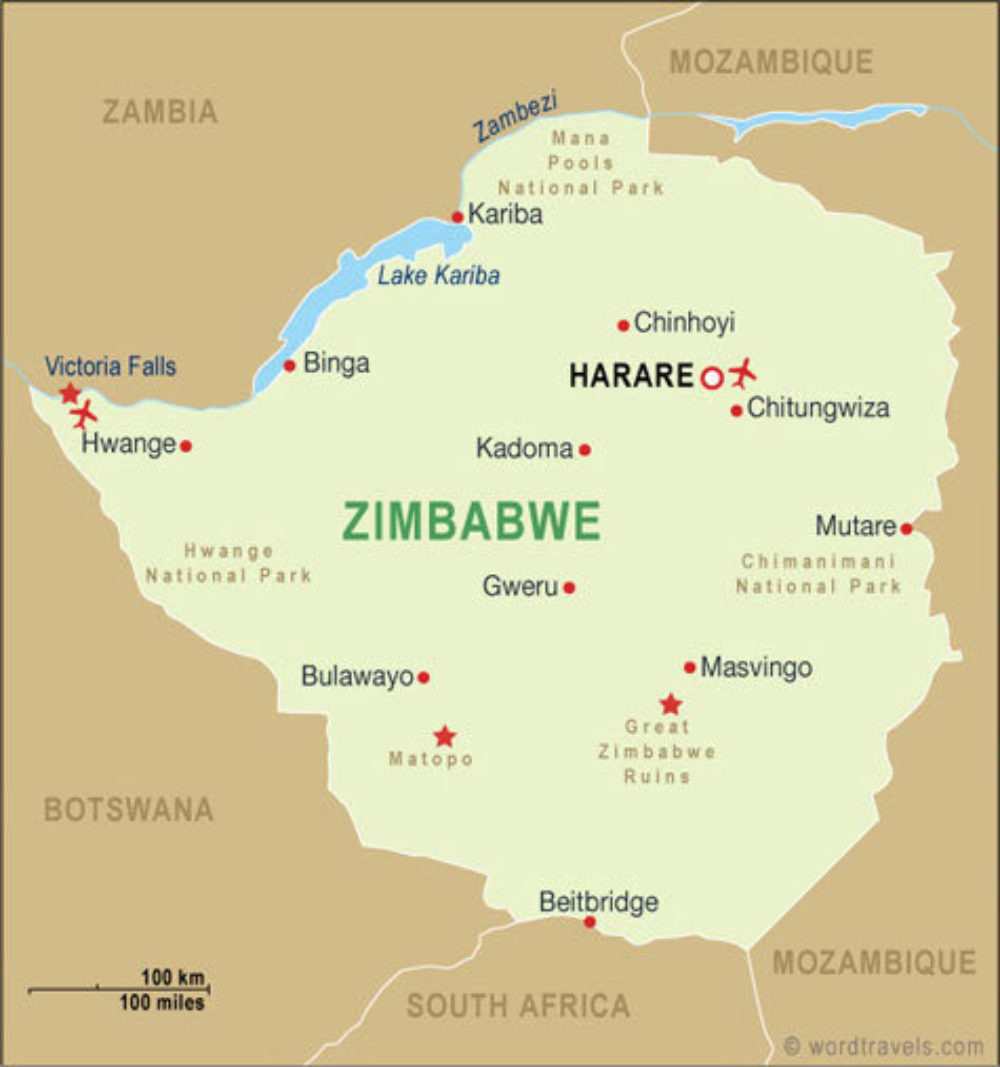

I was born in 1975 in Kadoma, a little town about 200 km from Harare in the countryside known as Mhondoro. My mom’s brother, Daveson Magunje was a healer and mbira player. Growing up with him is what made me learn cultural music. I admired everything he used to do. He helped many people heal and trained a lot of mbira players as well, including his brothers, Mathew and Bernard.

Daveson was a great spiritual healer. He was hired by people from different parts of Zimbabwe to play in healing ceremonies. So we traveled with him, performing in these ceremonies up until he died in 1994. Uncle Daveson was my main inspiration, culturally and spiritually, and his brothers and sons were excellent mbira players as well. I also spent time with other healers, including my late father, Lancelot Magaya, and I also sought out opportunities to learn from other groups and individuals, including performing in school groups. I had another uncle called Crispen, who lived in Kadoma. He made very strong mbiras, which I still use today, and he also taught me. I make mbira now, and Crispen was one of my main inspirations for this.

I grew up with my mother, Evangelista Magunje, who was the firstborn in the family. She was older than Daveson. When my mom found a job, she moved to Kadoma to work, and she took me to live with her in town, while Daveson stayed in the countryside. My mom and Daveson were very close and visited each other often. So I went to school in Rimuka, Kadoma. On school holidays I would often go to the countryside to visit Daveson, his family, Bernard and, above all, my grandmother, Violet Magunje. I would help her to plow, and I participated in ceremonies, learning about culture, herbs and so many things. Bernard was also attending school in the countryside. He was very good at school, and my mom assisted him with school fees. She worked as an accountant and was proud of Bernard when he graduated.

While I was taking my O-levels (secondary school exams), my Uncle Daveson died in Kadoma. That was 1994, and when he died, I was devastated. After Daveson died, his younger brother Bernard took more control in the family. By this time he had stopped playing mbira, graduated from university and become a strict Christian. Bernard tried to discourage our traditional cultural life. He encouraged everyone to go to school and follow Christianity. Chiristianity was not a problem, as we were already an Anglican family, and Bernard did a lot of good things for the family, renovating houses and sending Daveson's kids to school. But the fact that he wanted to stop our cultural ways was a big issue for me. So I took on that challenge. I also had to think of Daveson’s sons, Cephas and Shadreck, and others. We encouraged each other to continue with our culture.

After Daveson died, I decided to put a band together in Kadoma. We started performing with mbira and marimba. We did a lot of busking and played at places like Kadoma Grande Hotel, the Ranch Motel, and pubs and venues in Rimuka. In 1995, we decided to move to Harare, to the area called Highfields. We continued with busking, but also performed in places like the Ramambo Lodge, Pinsau, Mushandara Pamwe Hotel, Manjoro and such places around Harare. After a while, some of our band members gave up and moved back to Kadoma, and I had to find new brothers in Harare.

That’s how I met Dixon and Zivai, and brought them into the band. While we were playing gigs, we were also active at spiritual ceremonies. Healers used to hire us and take us to their ceremonies. They liked our group because of our energy; we could play very fast, making people dance, sing and go into trance. Later, when it came for me to arrange my own ceremonies, I had the guidance of these healers to help me.

What about your father?

On some holidays I would visit my father's countryside home in the Bumbe area of Mhondoro. He was also a healer, and he taught me about my family tree, my ancestral history and my totem, nungu, the porcupine. My father hosted large ceremonies regularly. He was a respected man in the community because he ran a chrome mine that employed many people, and he helped the community build primary schools. I was proud of my father and admired his ways too.

When you challenged Bernard over his opposition to traditional culture, was that a problem? Did it make a division between you, or did he accept that?

We don't share a lot in common, and our paths don't tend to cross any more. At the time there was some tension, but we have both progressed in our own journeys. I came to realize that Daveson’s father was distant from Bernard's father. Bernard's father was a priest, so he was just trying to be like his father. Daveson’s father was a healer, so he too was following that path. Daveson was more similar to my father.

Let's go back to the band in Harare. You mentioned Zivai. Is that Zivai Guveya, who played guitar with Thomas Mapfumo?

That's him. I met Zivai and Dixon in Harare when they were young. I'm probably nine years older than Dixon. So Zivai must be about 10 years younger than me.

Wasn’t it the Guveya family who had the mbira pop band Vadzimba?

Yes. That was the band of Washington Guveya, Zivai’s uncle. Zivai and Washington is like me and Daveson. I moved into the same street as Zivai's family and Vadzimba, and that’s how I met them. When we met, Zivai was a drummer, but then he started playing marimba. Shortly after I met Dixon, we formed this acoustic group with the brothers I had brought from Kadoma. We performed with just mbira, marimba, drums and shakers. But when I went to England the first time, my friend Mark bought me a small P.A. and a keyboard. When I brought these things home, Zivai switched from marimba to keyboards. Then when I went back to England the second time, I bought a bass and a drum kit, and Zivai left keyboards and started playing bass. And then when I brought a guitar, Zivai went to guitar. He liked to learn new things and worked hard to develop his talent.

He is an excellent guitarist. Which instruments do you play?

I play mbira, and marimba, hosho (shakers), also drumming and dancing, and I sing of course. I'm the lead vocalist and songwriter for our group, Zimbaremabwe. Now I also play guitar. I started learning here in the U.K. It was difficult here when I wanted to record or perform a full band set. I had to look for people to help me with guitar, so that motivated me to learn myself. I've been studying popular music at university and play chimurenga style too. My band members, Tim Lloyd and Andy Bay, have also helped with my guitar. I play guitar on some of our recordings and also perform now, which is something I'm proud to have achieved.

How did you manage to move to England?

My uncle Daveson used to go out with a British partner named Corin Ford. Corin was in England when Daveson became ill and died. Two or three years later, she came to Zimbabwe to grieve with the family, to see Daveson's grave and understand what had happened to him. By then, Corin had met a new partner, Mark Roworth, and they came together. My grandmother told them, “If you want to understand about Daveson's last days, talk to Linos.” This is because Daveson had been in Kadoma during his final days. So I left my band in Harare and came to visit them in the countryside for some time.

They could see what was going on in the family. Those are the days when Bernard was pressuring everyone to be Christian. Mark and Corin were happy, but they could not hear the mbira and the things that Daveson was into. But when they visited us in Harare, they saw that I had this band and I was following the culture, continuing the things Daveson had left behind. They tried to help me find gigs in Harare. We went everywhere, to hotels and clubs… But when they went back to England, I realized that those venues only gave me gigs because of Mark's presence. The moment he left, there were no more gigs.

I used to write Mark letters all the time, as I wanted to maintain the contact and friendship. Then one day, he wrote to say he would help bring me to England. The first two or three trips, I just went to play gigs and earn money to buy equipment to take back to my bandmembers. That’s how we ended up playing at hotels like Mushandira Pamwe Hotel where Thomas [Mapfumo] used to practice with his band. We had a residency there, so Thomas’s musicians would hear us every Saturday when we played in the garden.

Our promoter, John Nguruve, head of Music Time Productions in Bulawayo, was helping to promote Thomas. He booked us to support many of the big acts that came to Bulawayo, such as the Lubumbashi Stars, Black Umfolosi, Siyaya and other bands. He booked us at festivals and venues around Bulawayo. That’s how we performed on Thomas's stage as the support band maybe three or four times. John is the one who introduced Zivai to Thomas, and when I moved to England permanently in 1998, he brought Zivai into Thomas’s band. My idea was to find opportunities so my whole band could come to England, but in the end I was only able to bring Dixon.

So the band that I'm hearing on this album is all people who live in England and play with you there?

Yes. I have my friends that I met in Brighton and we've have been playing with for years. These are the guys I'm coming with to America. There's Andy Bay on guitar and backing vocals. We met in Brighton in 1999. Then I met Tim Lloyd in 2005, and we have been together ever since. He plays mbira and bass in the band. My brother Dixon is still our drummer and he plays mbira and Zimbabwean percussion—shakers, drums, dance. Zivai also helps on some of our recordings, mostly traditional songs. We each have our own bands, but are still good friends.

Let's talk about this album. Listening to it, I recognize a lot of traditional mbira songs. You have adapted them in a way similar to Thomas Mapfumo. What did Thomas’s music mean to you when you were growing up?

We grew up listening to his music, because he played the stuff we liked. I mostly know his music from the Blacks Unlimited. But even back when he was with the [Hallelujah] Chicken Run Band, he used to play a lot of different styles, including traditional. But with the Blacks Unlimited, he really started adapting mbira songs. Thomas' band used to come to Kadoma and we would go and dance. We had a collection of his albums at home. His style attracted me because it was bringing mbira onto a big stage and promoting cultural music in a new way. He was the first to guitar and electric keyboards and bass, and that's how they made that chimurenga sound. But he wasn’t the only one. His chimurenga and jiti songs still bring back strong memories and feelings for me. Sometimes it’s like being in a ceremony.

At first, he was using guitars to imitate mbira songs like “Taireva” and “Nhemamusasa.” I think it was Thomas and Pickett, the guitarist, who came up with this idea. Then there was Jonah Sithole [probably the most famous of Thomas’s guitar players, who died in 1997].

As an mbira player, I feel that the guitar style of chimurenga has to be the way these guitarists played, because the purpose is to interpret mbira. Any musicians deeply connected mbira should be able to play chimurenga. The name comes from Murenga (Sororenzou), a great ancestor from Mwenamutapa's kingdom. As a prophet, he left the kingdom and went to live at Mabweadziva, because he didn't like the bloodshed of the conflicts at that time. On the singing side, I like Thomas' style of singing a lot because he follows the way of mbira, which includes yodeling. However Thomas mixes politics with his spiritual messages, and this is not something I do. My singing is more connected with Daveson’s way; I write messages that connect people to their ancestors and spiritual life.

At this point electric mbira band music is a modern tradition. But I know there were a lot of bands that tried to follow that path in the early ‘90s. and it was hard for them. There was Vadzimba and Legal Lions; Pio Macheka and Ephat Mujuru had their bands; and Jonah Sithole had Deep Horizon. I think it was hard for them to escape Thomas’s big shadow.

That may have been true for some bands. Maybe there wasn't enough support for Zimbabwean culture and music, so it would have been hard to create a big music scene around this style. I think most Zimbabweans love chimurenga and mbira, but anyone who plays chimurenga, they think you are copying Thomas. This is unfortunate because it’s our traditional, cultural style and everyone is allowed to play it. No one owns it. I have played chimurenga for decades now, and some people still think that I'm copying Thomas. But I've listened to some of the interviews he's done since he moved to America. He speaks a lot of very good messages, and seems to be encouraging the youth in Zimbabwe to progress with chimurenga and cultural music. He collaborated with a lot of bands on his last trip to Zimbabwe which is encouraging to see. Zimbabwe really should be trying to uplift our traditional culture and cultural music. If Thomas is encouraging musicians, that sets a positive example for the generations to come.

Let's come back to your album and the lyrics you sing. I recognize the underlying traditional pieces on a number of these tracks. To me, those songs are almost like the blues form. They provide a structure that you can constantly reinvent to create a new song.

Exactly. As I was saying, in most of my songs I try to stay away from political messages. I mostly sing about helping people to understand our spiritual world, traditional power, and their health. When people live this way, they become friends with nature and that means they're going to have health forever. They are going to live stronger lives.

My songs try to bring people close to their ancestral spirits, and ask them to listen to their dreams. If we sing politics, we tell the ancestors to look after our problems. In our culture we have always told our ancestors about the country's problems and what we are facing in life. Before colonization, kings moved with prophets and would ask them for advice on how to govern. The purpose of our music is to restore the status of our prophets and put spiritual guidance at the head of the country, regardless of the interests of governments. Chaminuka is one of the prophets we call upon. But these names are disappearing because of modern culture, so we try to put these names back into people’s lives.

Tell me about the title song, “Mwariwe,” the title track from the new album.

“Mwariwe” is coming from a traditional song called “Muroro.” When musicians play “Muroro,” they mostly sing about the liberation struggle in Zimbabwe. "We took Zimbabwe back by war." They mention the names of sprit medium ancestors like Nehanda and Kaguvi, who were both killed in war. But this song existed before war, and in my version, I'm talking about the purpose of sanctified spirits in people's lives. It's good for people to receive the sanctified spirits from the clouds, from the moon, and from Mwari [God]. It’s good for people to go into trance and receive the ancestral spirits. This song is asking the Lord to look after people, to look after the nation, and to help people through, and asking people to pray and attend ceremonies. To be a sanctified person, you have to go into a trance where your ancestor possesses you and enters your body. This song makes people get possessed in spiritual ceremonies when it's played in the countryside. Now we play it with guitars and electric instruments, but it's still carrying a spiritual message, to say, “Father, look after us. Hey, people, receive the spirit from the moon, the sun, and the clouds. Let the come in your heart."

How many albums have you recorded over the years?

I have about seven albums of traditional songs uploaded online, but I have recorded quite a few more as well. I have also recorded in styles such as mbira reggae and I'm currently working on other popular music styles that incorporate mbira. There are quite a few interesting songs on this new album. There’s a song called “Chinzvenga Mutsvairo,” which was often played in my family. It is based on the traditional song "Nyama Musango” [a hunting song, literally “meat in the forest”]. In my version, I talk to men. Chinzvenga mutsvairo refers to a man who gets in the way of the broom when a woman is cleaning the house. So this woman is wiping up dust from the floor, and this man is never leaving the house. He sits there all the time and looks at his woman, arguing with her and the children instead of going out like other men to fight for life, work hard, and bring food home for the family. This song is telling off such a man. “Why are you chinzvenga mutsvairo?” The saying is a metaphor for a man who is selfish.

Then there a song called “Mhuri Yangu,” which means “my children.” It can be an ancestor crying to her children, a mother who died and her spirit is now coming back and crying, "Hey, look after my children. Don't beat them. I want my children to have a good life." It could also represent a person who is very poor in life but wants to see her children living better. The song also says about how blessed are those with mothers and fathers.

My father and mother are dead. The song has two sides, the sad part where parents are separated from children, but also encouragement for parents who work hard for their children. Even when the message os serious, chimurenga music gives people energy to dance and express themselves.

It's a lovely album. I understand you're coming to America this summer if all goes well. Have you ever been here before to play music?

I have never been to America before. This will be my first time.

What is the plan?

When I come there, we're going to perform at the Zimbabwean Music Festival. We will be performing as a band as well as doing workshops on mbira, marimba, drumming, singing. We can even teach people chimurenga guitar. Then, we hope there will be a few more gigs. We have a friend who is helping us book gigs here and around.

Well I hope we can get you over to the East Coast. I understand people are working on that. [Readers, watch this space.] So good to speak with you, Linos.

Thank you.