Lucy Durán is a London-based scholar, music producer, broadcaster, musician and longtime friend of Afropop Worldwide. Among her many specialties is a profound understanding of Mande culture in West Africa. So when putting together an homage to the remarkable life of Baba Sora (Fountanga Babani Sissoko, 1945-2021), we reached out to her for context and insight. Baba Sora was perhaps the most generous patron of griot musicians in modern West African history. His story of mysteriously, and ultimately duplicitously, acquiring great wealth is balanced by his passion for giving it all away, often to musicians. It’s a story for the ages, and Lucy Durán has much to say about it. Banning Eyre reached her by Zoom on Oct. 9, 2021. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Lucy, this whole story of Baba Sora takes place in the context of a long-standing tradition between griot musicians, jelis, and their patrons. Let's start by having you give us an overview of that tradition.

Lucy Duran: The way that things work in Mande griot culture, is that you have the jeli who is a hereditary musician, born into a lineage of musicians. They don't necessarily all play music, but they are all considered griots, and they all have a knowledge of the art of the griot. And then there is the jatigi. That's the Mande word for patron. So you have this symbiotic relationship, which has been going on for centuries, where you have a patron who takes care of the griot, and his or her family. They are very close friends. They know each other really, really well. That is all that the griot does. They are not farmers. They don't cultivate the land. Everything is given to them by their jatigi, by their patron.

This is the model of patronage that has been going on for centuries, and as you would expect, with colonialism and then with independence, that has all changed dramatically. The old long, generation-after-generation relationship between patron and griot if you like, jatigi and jeli, that's all changed. It does survive to some extent, but nowadays griots consider anyone who asks them to play at a concert or sing at a wedding party, astheir patron.

But Baba Sora really modeled himself on the old type of patron. If he was your patron, that was it. You relied on him. He did everything. He gave you cars. He paid for the petrol for your car. He gave Kandia Kouyaté a small airplane so she could fly up to Dabia, which is quite far away from Bamako, to entertain him and his family. That's the kind of level of old-school generosity and patronage that Baba Sora cast himself in.

However, it has to be said that Baba Sora himself was a jeli. He was born into a griot family. He never played music, but he was incredibly musical. Other members of his family were musicians. His mother apparently was a singer, and he had very profound knowledge of the jeli repertoire, particularly from his region, Dabia and Kenieba, which is on the border with Senegal and Guinea. It's a region that's very rich in gold. A lot of the gold of Mali comes from that region. And it also is the region of, to my mind, some of the most beautiful music of Mali, if not of Africa. I mean just incredible melodies. Every time I hear a beautiful melody that the jelis sing and I ask them where is that from, they say, "Oh, it's from Dabia." Or "Oh, it's from Kenieba.” So it's just one of those regions that has produced gold and melody. And Baba Sora was born into that region and had deep knowledge of music. He knew a good tune from a bad one. And he also knew a good musician from a bad one.

I have to ask you about that airplane. One person I spoke with recently said that that story simply wasn't true. And someone I spoke with back at the time I was living in Bamako, in the mid ‘90s, said it belonged to to Omar Bongo, the president of Gabon at the time, and that later had to be returned. So I want to hear your take on this. But first, tell us who Kandia Kouyaté is.

Kandia Kouyaté I would say is the greatest female voice of Mali in the late 20th century. She is a jelimuso, a female jeli, enormously popular. She was often on television. She has incredible charm when she sings, and she has a real deep knowledge of the jeli tradition, the griot tradition. She was absolutely tops at the time when she met Baba Sora Sissoko.

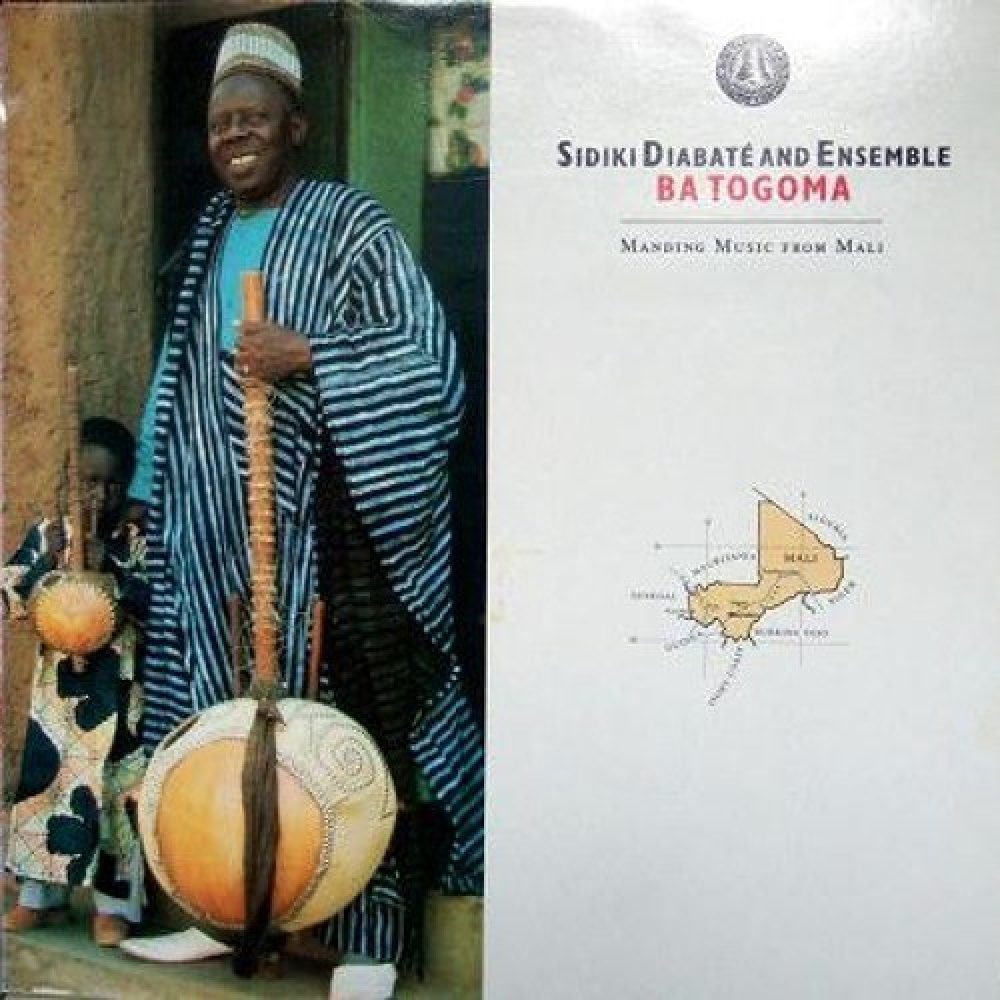

I first met Kandia In Bamako in early 1987, and I was completely blown away by her voice. I couldn't believe how beautiful it was. I managed to bring her to a festival in London, a BBC festival called Music of Royal Courts. She came with an all-star team, Sidiki Diabaté, the father of Toumani Diabaté, an incredible kora player, and other great musicians. We thought it would be a good idea to get them into a studio and record an album, and so that album became Ba Togoma, and one of the tracks on it was dedicated to Baba Sora Sissoko.

It’s called “Kounandy la Beno,” and like a lot of jeli music, it's highly metaphorical and actually quite difficult to translate. It's a metaphorical way of praising someone who was very, very generous, almost to an excess, someone who was "blessed with luck." That's what kounandy means. “Kounandy la Beno” says when you sow a seed it spreads and grows very quickly. So the generosity of Baba Sora, this man blessed with luck, spread far and wide. It allowed many musicians to dedicate themselves to their profession instead of having to grovel around and sing just any old thing for anyone. So it was a tribute to him as a great patron in the mold of the old pre-colonial patrons, the kings and the warriors. And of course the musical accompaniment is jawura, the music of his region, music for farming. It's all part of that metaphor of cultivation. When you cultivate the land, you grow things that give life, and that's what Baba Sora Sissoko did.

Beautiful. Now about that airplane...

Kandia Kouyaté was one of the people, one of the voices, that Baba Sora most appreciated. He certainly considered himself a patron of hers. And she told me, without boasting or anything like that, "You know, I've been given a plane. I've been given a very small plane. It's a two-seater, and obviously I don't fly planes. So I have a pilot and he comes and he picks me up when Baba Sora wants me to be in his home village in Dabia, because it's too far away to drive there and then come back the same day. He's built an airstrip especially for small planes like this, and I have a petrol account in the airport, and they just fill it up. I don't pay for a thing, and off we go.” Now whether it was a plane that was on loan or had been borrowed, I don't know. But as far as Kandia was concerned, she had been given a plane, and that plane was used to take her up to Dabia to sing for Baba Sora and his family.

That’s pretty definitive. O.K., now I’d like to take you through a bit of a timeline of Baba's early life. Here's what I've been able to piece together. He's born in 1945 and in various versions of his childhood there is this theme that he was not interested in being a griot, which frustrated his father, and that he was seen as distracted, even a bit incompetent. It's a little bit like the Sunjata story in that way. He was selling coffee by the cup. Then at a certain point he disappears. We hear about him traveling to Senegal, Gambia, India. Something about selling fabrics in India. I heard another story about Mobutu and diamonds. Then he returns, it must be sometime in the 1970s, and he has money and is this when he puts a lot of money into his town Dabia?

No, no, no. That was in the ’80s when he came back from Gabon. He made a huge amount of money in Gabon.

O.K. Good. But do we know any more about his earlier life?

Well, it’s true that the first part of Baba Sora’s life is shrouded in mystery. But I did hear stories about him going to Senegal in particular. Senegal is 20 km away from Dabia, So it's not a big deal to go to Senegal.

But India?

India is a little bit of a bigger deal. But the way it has been explained to me by all those people that I hung out with like Douga Sissoko [Baba Sora’s brother] and Tiekoro Sissoko [a griot guitarist] and all his musical mates... They would say, “He's a wanderer. He’s a stranger. He's an adventurer. He likes to go to new places and see what he can discover there, and how he can make things happen.” Apparently, he was always someone who wanted to be a catalyst for something happening. He was always on the lookout for that. And that's very much also in the pattern of jelis in the old days. You know, they were always wandering, going from one place to another looking for a new patron, or one patron would send them to another patron. There was a whole sort of network of patrons, people who had fought together in the precolonial period and then joined forces, or even fought against the French in their early attempts to colonize that whole region.

Baba Sora’s mates also told me that he never went to school. He couldn't read or write. But he had a kind of innate intelligence, and also the ability to suss people out. He had great insight into character and intelligence. They also described him as a very gentle human being. And the one time I met Baba Sora, I was very touched and moved by that gentleness, because I didn't expect that, given how wealthy he had been. But that is all I can tell you about that early period.

In our program, the balafon player Lassana Diabaté tells a story of how Baba Sora married the sister-in-law of Omar Bongo. And when we spoke with Kandia Kouyaté, she said that Baba had many women and many children but only one wife. Is that the same wife?

No. I don't think so. I think she stayed in Gabon. And I don't think it was a sister-in-law. I think it was a niece or a daughter. I might be wrong about that. I would trust what Kandia Kouyaté says. She would know.

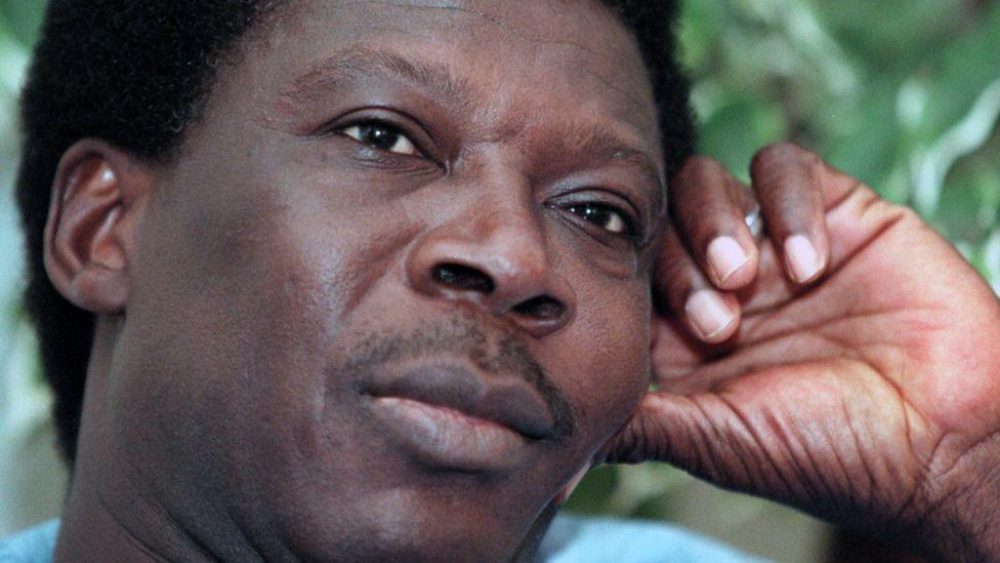

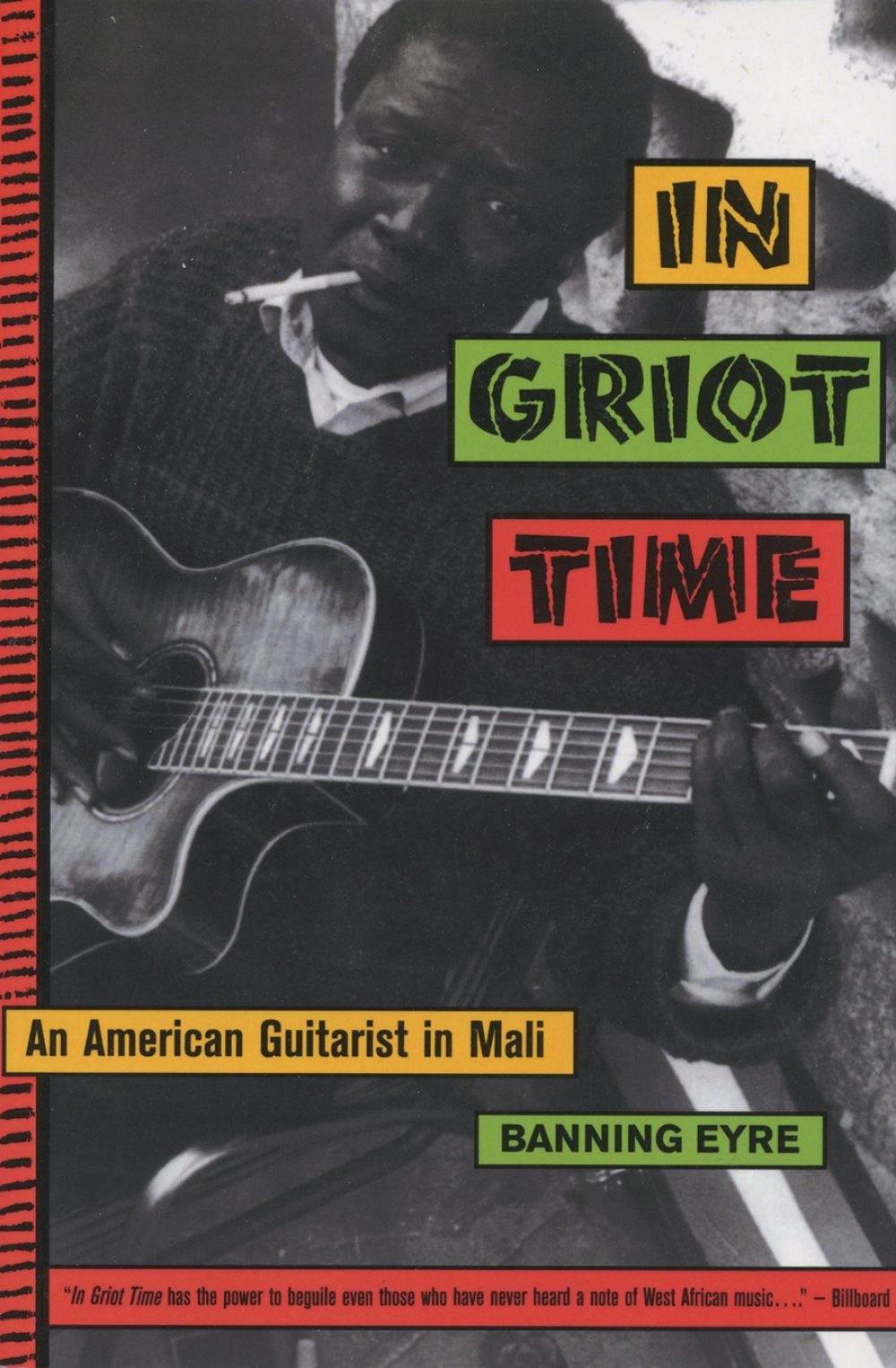

O.K. One wife; many children. How about this? When I interviewed Salif Keita back in the 1990s for my book In Griot Time—years before he wrote the song “Baba” in praise of Baba Sora—Salif spoke well of the man. And in my book, I commented on how interesting it was that Salif is a noble who took on the role of the griot, and Baba is a griot who took on the role of a patron, a noble. What do you make of that?

Well, it is interesting that Baba Sora became a kind of a patron of Salif Keita. Because there is Salif Keita who is in theory descended from Sunjata Keita, the founder of the Mali Empire, the ultimate incarnation of royalty, if you like--very much a noble. They're not supposed to sing or to play music at all. They are the horon, the free born, not born into a profession. So there is Salif, who despite having been born to this noble heritage, he's a singer. And in fact, almost all of Salif’s music is drawn from the griot tradition. A lot of his tunes are taken directly from that region where Baba Sora was from, the Malinke´ or Maninka region. And then you have his patron who is in fact a griot himself, and yet he has cast himself in the role of the patron, the noble.

So it is fascinating that these two men have sort of switched their roles, or exchanged roles. But to my mind,that is one of the wonderful things about Malian culture and Malian society. Nothing is really set in stone like that. You can talk about it like that, but the reality is there are many griots who behave like nobles and have never sung a note in their lives. And then you have many nobles who are very musical, I mean all the Wassoulou musicians. They're all of noble heritage and they're not griots. So nothing is quite as binary as it would appear.

Do you think Baba’s early training as a griot might have helped him gain peoples’ confidence in his later exploits?

The thing about being a jeli, a griot, is that you do get training as you grow up. I know about this because I followed the training of young griots in their families for that project I did called Growing Into Music. There is a lot of philosophical stuff about insight into the human psyche. A griot needs to have that kind of sensibility and knowledge. A lot of the older generation of griots did not go to Western schools. They're not reading Jean-Paul Sartre or anything like that, but the really good ones have an uncanny hook on the human psyche. It’s clear that was one of the gifts of Baba Sora. He had that ability to understand and get under the surface of things and really know people, and also, possibly for the same reason, to be able to fool them or persuade them.

I want to tell you about something that happened one of the times Baba Sora came back to Mali, probably in the late 1980s. He arrived, like the return of the hero, and all the jelis were in such a state of excitement. The head of the griots in Mali organized a huge party in the big field in the west of Bamako, where the old airfield used to be. And so there were dozens and dozens and dozens of griots at night, in the evening, in the dark with their drums and their various instruments. Hundreds of female griots dressed to the nines gathered in this enormous circle, shuffling around, doing their griot dances. And he didn't show and he didn't show and he didn't show. And then he turns up in a car, a Mercedes probably, and he drives into the circle where they were drumming. And he actually drives backwards and forwards rocking the car backwards and forwards in time to the drums, in time to the dancing. And people just went completely mad. This was not just their patron. This was a fellow jeli who really understood the music. That was it. He really knew their music from the inside, and there he was in a car driving, just very gently rocking that car. It was an amazing scene.

What a story. That's wonderful. You know I realized going back to my book that you and I met for the first time in Bamako in 1996, right amid the excitement of Baba’s return with all that money.

That’s right. And there were lots of stories about Baba Sora being able to perform supernatural feats. There would be an ordinary trunk. It would be absolutely empty. And 10 minutes later, you opened it and it would be packed full of money. So everyone would shriek with delight and astonishment. How did that money get there? This was his magic power. And people believed that. They really believed it.

And you will remember, his house in that part of Bamako called Hippodrome, which is kind of the expensive part of Bamako. I mean, day and night, day and night, day and night, there were just hundreds of people, sitting on the ground, sleeping all night, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting to see him, queuing up to see him. They would go in and they would say, "My grandmother needs an operation, can you help?" And he had all this money bundled up, and he would give money out, just like that. So he won a lot of fans, even when it was finally discovered that he had actually stolen this money, or had it stolen for him from the Bank of Dubai. Malians didn't care, because he had been so generous with them. He didn't use it to build himself palaces or anything like that.

Absolutely. All the people I interviewed in Mali were very clear about this. I particularly loved Kandia Kouyaté’s response when I asked her how she felt when she he had got the money from the Bank of Dubai. Her response was, “Allah akbar!” God is great.

And of course I do recognize the scene you describe. I experienced it twice. As I was looking back at my book the other day, I saw this quote from Charles Bird and Martha Kendall about the Mande hero being an “agent of disequilibrium." Sitting on the sidelines of this whole phenomenon back then, I saw the kind of frenzy that his presence created among the musicians, and I think that's why that characterization hit home for me. Any thoughts about that?

Yes, there is no doubt that when Baba Sora appeared on the scene in 1996, it was like honey to the bees. Everyone was scrambling for a bit of money from Baba Sora. It did kind of turn everything upside down. And one of the most famous and unfortunate consequences of that disequilibrium that he created unwittingly, was that Djelimady Tounkara, the guitarist, your host and teacher, and Bassekou Kouyaté, the ngoni player, were both invited to participate in an album with Ry Cooder in Cuba, and they didn't make it. Whoops. There were a lot of theories about why they didn't make it did, but essentially, I think the reality is that Djelimady in particular was tempted by the return of Baba Sora to stay at home and not take that trip. What was he going to get from Cuba when he had Baba Sora on hand?

I was in the middle of all that. Djelimady always claimed that Baba Sora had nothing to do with his missing out on Cuba. It was all about passports being misplaced in the Cuban consulate in Burkina Faso. I doubt we'll ever know the final truth, but if that original plan had gone ahead, we never would've had the Buena Vista Social Club. And it's hard to imagine that any album they could've made would have competed with that outsize success.

It would've been a completely different album. And we don't know how successful it would have been. It wouldn't have had quite the same riveting back story.

We could talk about why the Buena Vista Social Club was so enormously successful, I mean beyond anything else in world music. But that would be going down another rabbit hole. We'll save that for another conversation.

I've just been teaching about that, and I do have some pretty good ideas. But you're right. Let's stay on subject. I want to comment on this idea of Charles Bird and Martha Kendall about the hero being the agent of disequilibrium.

Go.

You have these two words in Mande, Maninka and Bambara ngara [nya-RAH] and ngana [nya-NAH]. These are important ways of talking about heritage in Mande society. So you have the ngara who is the great master of the griots, or any of the artisans. They use almost magical supernatural powers. They say that the really great griots could make a door crack open in two with their voice. All the leaves would drop off the trees. These are the ideas around the ngara. Their counterpart is the ngana, and that is the hero. The ngana is the one who goes out and physically does things. The ngara does things with supernatural powers. The hero, the ngana, is an interesting character, not always doing good things. They can be like the sorcerer king, the blacksmith king. They can also be terrifying and brutal. So in a way, what you see in this incredible character of Baba Sora is that he's partly ngana. He is partly a hero. But is also a ngara. He's also a great master. And you put the two together, and he managed to persuade the Bank of Dubai to give him millions and millions and millions of dollars in the process. It's quite amazing.

O.K., let's talk about Dubai. To me the biggest mystery in this whole thing is how exactly he pulled off this act of persuasion, and maintained for nearly two years. Maybe you've read the Miami New Times article by Jim DeFede called "Baba’s Big Bucks." It's from July 1998, and this is the article that blew open the whole story about Baba’s gaining the confidence of a bank officer and withdrawing over a period of time $242 million. The general reaction and in Mali was, "No problem. The world is full of thieves and most of them just look after themselves. Very few come back to their own country and build the nation.” I sensed absolutely no problem with the ethics of this. What's your take?

You know, it's so interesting. When you Google Baba Sora, what you find is that he is invariably described as a schemer, a swindler, a thief, a con man. And none of these reports mention the fact that he was also a great patron of music and the arts.

And his country.

And his country. Certainly his town. He razed all the buildings to the ground in Dabia, and he rebuilt everything in cement. Everything before had just been in straw and mud brick. And he built a hospital. He built schools. He built an airfield. He did a lot for his country, and no one mentions anything about that. If you think about what he managed to do as a patron of music, you have to think about how much less music we would've had, wonderful classical music, if Beethoven hadn't had a patron, if Mozart hadn't had a patron, if Bach hadn't had a patron. This is what Baba Sora did.

He didn't hurt anybody physically. He robbed from a bank, not from an individual. I don't know. O.K., clearly he was a brilliant con man. How did he manage to persuade? He obviously had incredible charisma and persuasive ability, which surely comes out of his griot heritage. But he didn't hurt anybody, so I sort of feel a bit angry that he's always described as a con man. Because he's much more than that. Much more than that.

There are many articles including in the New York Times and the Washington Post from the time he was in Miami and they talk about his incredible generosity to people there. He famously gave $300,000 to a high school brass band so they could travel to a competition. These were things that these reporters knew about. And of course, Baba was a bit of an agent of disequilibrium in that context also. But I certainly take your point. I feel that also. You mentioned that you met Baba just one time, after all the Dubai hubbub.

Yes. It was in 2010. When I was working on my film project Growing into Music in Mali, I was spending quite a bit of time, two or three times a year, six weeks at a time based in Bamako, which was wonderful. I stayed with a friend in her house in Hippodrome, and it happened to be bang opposite of Baba Sora’s house. He was a deputy in Mali’s national assembly.

Right, I understand that this was how he avoided arrest. He had diplomatic immunity.

But by then, he was seriously out of money. His funds had finished, and one by one, the lights went out in his house. It was kind of sad. And then he started clearing things out of his house, or somebody started clearing them out. And so suddenly that was all this kind of Louis XIV furniture, which looked so out of place on the sandy street in front of his house in Hippodrome. And no one touched it. No one touched any of his furniture. That's how much everyone respected Baba Sora.

And one evening, Bassekou Kouyaté, the ngoni player, and his wife Ami Sacko, who are great friends of mine, went to see Baba Sora, and they brought him to meet me. I came out of the door of my friend’s house, and it was dark. It was the evening. This was the only time I ever met him, but we had such an interesting conversation. It was just straight off the deep end, talking about all sorts of philosophical things. He was asking me what I knew about Malian jeli culture. And then I sang that song, the song that Kandia had sung for him. (sings “Kounandy la Beno”). He was amazed and asked, "Do you even begin to understand what that metaphor means?” Then he started explaining it to me and I was completely gripped, and I thought, "This is a very special, thoughtful, gentle human being.” He'd lost his money, but he hadn't lost his dignity at all. From there, he went back to live in Dabia and I never saw him again. But I feel very privileged that I got to meet him.

That's lovely, Lucy.

So he's such a fascinating man, controversial man. But I think his great contribution for at least a while was that he really encouraged artists to slow down their music to be more profound in the way they played and what they sang about, to not be what Kandia calls “the pam-pam-pam and the boom-boom-boom.” He didn't like that. And he also loved the outer reaches of Mande culture. He loved music from Gambia, from Senegal. He was very catholic in his musical tastes within Mande culture. And unfortunately, that's completely gone, that aesthetic, closer to the tradition, closer to the kind of sharing of repertoires that was happening in the early 20th century. Now, he'd be turning in his grave. What might he have thought about dancehall and reggaeton and all of those styles that are taking over now, so unlike the aesthetic that he loved?

Have you seen that YouTube video of the kora player Balla Tounkara playing for Baba Sora on a rooftop?

Yes I have. I knew Balla from way back, and Boston in 2000, he told me the story about how he jumped up and sang at one of Baba’s soirées in 1996. He was just a kid at the time, and Baba wrote him a check for $12,000. That's how he came to America and stayed for some 10 years. But in that video you’re talking about, he's back in Bamako. It's 2018. And basically he's playing for Baba as a poor man who doesn't have the ability to give him much of anything.

Well, he probably got something. Also, he got prestige. But as I said, the thing that struck me when I met Baba Sora was his dignity. And I think you see that in that video when he's on the balcony with Balla playing the kora for him. You see his dignity.

That's true. And I certainly felt that when I was able to interview him back in 1996. He says some very wise things in that interview. So, Lucy, I know that Kandia Kouyaté was at the top of his list of female griot singers, and that list includes Babani Koni and Nainy Diabaté. Ami Koita. Others no doubt.

Don’t forget Tata Bambo Kouyaté, who also passed away this year. She has that wonderful song, “Homage àBaba Sissoko,” which is based on the traditional song “Bambugudji.” He paid for that recording. That's actually in your interview when you met Tata Bambo in New York. You interviewed her and she said that.

Oh really? That was a long time ago. I have forgotten.

She talks about Babani. She says, "He invited me to Gabon, and I said I couldn't come because I had things I had to do in Paris. And he said. “Oh, you are in Paris? Then I will meet you in Paris.” And then he paid for her to do that wonderful recording with a number of great musicians. But he specifically said to her that the song he wanted her to sing for him was “Bambugudji.”

That’s the song about the Segou king who lived far from the river and built a canal so his wife could see hippos out her window?

Well, yes, but he [Bambugudji] was also the rightful heir to the throne in Segou. His place was usurped by his younger brother. That's why he was banished to Bambugu and there was no water in Bambugu. So the jeli women came every now and then to Bambugu to make fun of him. And apparently they would go there and get up close to him and say, “Pugh! You stink. Don't you ever wash?” I'm not quoting this exactly, but they didn't want to sing for a king who never washed. And what that did was it forced him to bring water to the village.

Oh. I always thought it was about the wife wanted to see the hippos.

Well, that's the nice story. The real story is that they taunted him and told him, “You all smell because you don't have water in your village. And you stink.” And meanwhile the wife said she wept because they had been banished from the Niger River. She missed the sound of the hippos. If you read David Conrad’s book with the line by line description of this song, performed by the great jeli Tiyiru Banbera, he tells the story in great detail. It's very memorable.

Interesting that Baba liked that song so much. I remember that when I went to one of those soirées in 1996, Djelimady’s brother Madou told me that I should learn that song because he loved it. I did learn it. But I never got to play it for him. Anyway, Lucy, thanks so much for all this. You’ve really filled out the jeli side of this amazing story.

There's a wonderful, very metaphorical proverb that the jelis quote when they're lamenting the death of a great patron, and it goes [sings]. It’s called Yiriba Boita, and it says, “A great tree has fallen. The birds have all scattered.” And the birds are the jelis.

Related Audio Programs