This is Part 1 of a series on the exhibit From Timbuktu to Washington, presented on the National Mall from June 25 through July 6, 2003.

The 37th Smithsonian Festival of Folklife brought a massive exhibition of Malian music, dance, artistry, films, craftwork, food, language, fine clothing, and best of all, people, to the National Mall in Washington, DC. The Festival this year also celebrated Scotland and Appalachia in similar dimensions. What unifies these three? Well, on the simplest level, you might say Appalachia is what you get when you combine Scotland and Mali. While the deeper promises of that global dialogue may not have fully played out at the festival--for the most part, these remained three distinct exhibits--the connections were certainly there to be seen and heard.

From my perch as a presenter at the Bamako Stage during week one and the Timbuktu Stage during week two, I rarely got out of the Mali music zone while on the festival grounds. But back at the hotel at night, over one-dollar beers and Scotch whiskey, musicians did share across cultural divides. Bagpipes wailed against djembe drum rhythms, and a few brave fiddlers and guitarists tried to weave their way through balafon and kamelengoni rhythms. More on that in an upcoming report. First and foremost, this was without a doubt the richest and most extensive exhibition of Malian cultural and musical variety in American history.

Opening Day

The pageantry of opening day on the Mall was capped by the appearance of Malian president, Amadou Toumani Toure (ATT), who has made this festival a priority since he was elected last year. The curator for the Mali exhibit, John Franklin, proudly reports that he had the first scheduled meeting with ATT after he assumed office, and from that moment, there has been no doubting the president's commitment to making Mali's representation on the Mall nothing short of spectacular.

At the opening ceremony on June 25, Toure delivered a quick tour through Malian history and geography, citing empires, the glories of the cultural crossroads at Timbuktu, and cosmopolitan Mopti--"Mali's Venice"--and celebrating the "legendary beauty" of Malian women and the diligence of Malian men. Toure concluded by declaring his nation an example of "democracy and tolerance…tradition and modernity," and announcing to hearty applause that, "We have brought Timbuktu to Washington."

Appalachia sent two congressman--Bill Jenkins of Tennessee and Rick Boucher of Virginia--and Scottland sent a full-throated singer named Sheena Wellington who belted out a melodious rendition of a Robert Burns poem, and also the Minister of Tourism, Sport and Culture. But it was hard to compete with the grandeur of a democratically elected African president.

After the ceremony, Toure, resplendent in his sky-blue boubou, moved about the grounds, shaking hands, taking in snatches of performances, and posing for photographs. That night, at a special evening concert of Neba Solo and the Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, ATT sat in the front row, beaming as dancers and singers regaled him. He might have been a president, but first and foremost, he was one of many proud Malians present, and his warm words from the stage underscored the momentous nature of the occasion and proved genuinely moving.

Toure had certainly marshaled the forces of his government behind the festival, but that's not to say that all went smoothly. A massive shipment of materials to be used in the non-musical exhibits had left Bamako late, and during the first two days of the festival, the artisans presenting in the Malian village were a little forlorn: blacksmiths without iron, potters without clay, weavers without looms. Working through their translator/presenters, they did their best to explain their arts, but it wasn't until Friday, June 27th that the village really began to take on a full-blown Malian ambiance, with sewing, dying, jewelry making and leather work going on amid wafts of incense, green tea brewing, and savory peanut sauce simmering in the cooking tent. The air was alive with chatter in Bambara, Songhai, Tamasheq, French and English.

Meanwhile, masonry work continued on the archways of a building in the colonial Segou style, which rose between Tuareg and Songhai tents, the Dogon togona, and the towering Smithsonian castle. To the West lay Appalachia, Scotland and the Washington Monument; to the East, the Bamako and Timbuktu Stages, a replica of the adobe arch of Djenne, and the Capital Building. Throughout the ten days during which this miniature of Mali thrived on the National Mall, there was music everywhere.

Tradition!

The music of Mali is so vast that the task of selecting roughly 120 musicians and dancers who could represent it fairly must have been daunting. Given Mali's looming stature on the contemporary Afropop scene, the Smithsonian curators were committed to bringing some of the top names in the country's modern music to perform special concerts on the site. The choice came down to Salif Keita, Oumou Sangare and Ali Farka Toure. Devotees of Habib Koite, Toumani Diabate and others grumbled here and there, but the selection was solid, both because it represented three broad streams in the country's contemporary music--Manding pop, Wassoulou, and the music of the desert north--and also because these are impeccable acts, guaranteed to deliver, which they did. More on that in an upcoming report as well.

The remaining fourteen musical acts come almost entirely from the ranks of ethnic traditional music. With the exception of Kenaga de Mopti--a regional band going back to the 1960s--none of these used electric guitars, keyboards or almost any modern trappings. With the exception of the Tuareg ensemble Tartit and the Senufo balafon group Neba Solo, and Instrumental Ensemble of Mali, none have CD releases on the international market. This selection inevitably meant bypassing some groups near and dear to the hearts of Afropop Worldwide. We have paid a lot of attention to middle-range roots pop acts like Lobi Traore with his Bambara blues and Haira Arby, the "Nightingale of the North," whose act blends the Songhai njarka fiddle and calabash percussion with fleet electric guitar, bass and drums. In short, these are acts with one foot squarely in the modern music world and one in the traditional.

While acts like these would certainly have done Mali proud, there was good sense in digging down to deeper, still more hidden realms of the country's traditional music. And after a day of watching the groups that were chosen, I was convinced. There was no way to show it all, but the curators had selected well, bringing us both the familiar, as well as some dazzling surprises.

The detailed selection was spearheaded by Kardigué Laico Traoré, a veteran of Malian television, which has an excellent record of supporting and promoting traditional music. Kardigué must have faced a real political challenge with so many artists he has worked with over the years eager to have a place on the Washington-bound caravan. But in the end, the selection was made, and two plane loads of Malians arrived in DC, just as weeks of cold and rain came to an end, and the more familiar seasonal weather--hot and humid!--settled in.

A number of the Malians in the delegation had not traveled in Europe or the U.S. before, and the Festival and hotel staff at the Key Bridge Marriott had their hands full dealing with such matters as air conditioning. For a Malian used to a hot dry climate and open-air living, windows that don't open and devices that render the air as cold as a refrigerator seemed more like madness than technological wonders. By opening day, though, everyone seemed to have adjusted, and the musicians arrived on the site ready to give their all. Hard work lay ahead. For the 14 core groups, each day would include two, three, sometimes four performances.

So Fing: Mysteries of the Fishermen

One of the most extraordinary and unexpected groups came from the shores of the Niger River near Segou, specifically the town of Marcala. The group is called So Fing, which means "Black Horse," a reference to a mystical being from the world of spirits. The Boso are an ethnic group long associated with the life of fishing and the river. The Somono are not an ethnic group as such, but rather a people of various origins who have chosen the fisherman's existence. Both live and die by the fortunes of the Niger and other rivers, and both are represented in the group So Fing.

The first thing that hits you about this group is the voice of its lead singer, Mariam Thiero. It is a clear, rich, piercing voice, bursting with mystery and melancholy. It is unlike the proud belting of the Mande jelimusow (female griot singers), or the nimble, bird-like melodies of women singers in Wassoulou--indeed, it is unlike anything. Each So Fing performance began with Thiero wailing into the microphone in a slow, patient cadence that could absolutely hypnotize an audience.

Behind her, dressed in white tunics and black leggings tied at the calf, as if to allow wading in shallow waters, stood four drummers. Their instruments--bafo, tenemoukou, tambo, and gangan--each produced a different sound. All had wooden bodies and taut, skin heads lashed on with arrays of twine lacing that ran the length of the drum. But while one was played with a heavy club and produced a deep thump, others were played with a hand and a thin stick, like a Wolof sabar drum. The highest sound was a sharp crack, and when all four played together, the combined effect was rich, complex, and quite distinct from any of the many percussion traditions represented in Mali's musical delegation.

The pacing of So Fing's music was also remarkable. Mariam Thiero's haunting vocal contained words of thanks to Allah, but also invocations of the spirit world, particularly the spirits of the river, and of fish, forces that guide the success of the catch. She also sang about the bravery and endurance of fishermen. A feeling of hopefulness and waiting was palpable each time. Then there would come a moment when something in her vocals would signal the drummers, who would then lurch into a pounding volley of rhythm. Thiero's vocal would wail on, only now all but drowned out by the cracking and thundering of the drums. Thiero and her drummers would then sway in graceful, long-armed gestures, as if in the frenzy of tossing nets over waiting schools of river fish.

After a time, the excitement would end abruptly, and the mood would return to reverence and waiting as Thiero's voice again emerged as the dominant element in the sound. All this would have been thrilling enough, but So Fing is also renowned for their remarkable use of enormous marionettes. They couldn't bring their entire set of marionettes, which includes hippopotamuses, various fish and other water creatures. But the marionette they did bring, a 12-foot long, sharp-toothed, fully finned fish, was enough to give audiences the feeling of their full act.

At a certain point, Thiero would direct her singing off stage, and a sole drummer would come forward, calling to the fish, which emerged like the spiritual incarnation it was from behind a curtain. The fish's moves were extraordinary. Sometimes it would raise a tall spinal fin and wave it playfully. Other times it would lurch forward and backwards, evasively, even menacingly, wag its tail nervously, or open its jaw to show off its sharp, four-inch-long teeth. At the Bamako Stage, the Malian stage manager Modibo Diallo would sometimes grab a small child from the audience and drop him or her on the fish's back for a ride. But just as often, the fish would lunge forward at the audience, momentarily terrifying children. The way this act played the line between fun and fear never failed to make a deep impression on audiences.

Each performance was a little different, evidence that the performers improvised the action depending on their mood. Sometimes a drummer would set his instrument aside and reach for a huge, circular, nylon net with weighted edges. In a single, deft twist of his body, he would hurl it into the air, completely entrapping the fish as the drums thrashed and Thiero cried with the exhilaration of a successful catch. Other times, the drummer, or Thiero would simply lead the fish around the floor, moving through cycles of tension and release in the music.

Mariam Thiero said in an interview that she began singing as a young girl, but first worked in the context of popular music in the eastern Malian city of Kayes, where she lived for a time. At a certain point, she decided to go back to her Boso roots, returning to Marcala to form So Fing. She has been a legend in that region for many years now, performing with the group at weddings, parties, and village celebrations that sometimes last until dawn.

The Desert Zone: Baba Larab and Ensemble Tartit

Given Afropop's extensive coverage of the Festival in the Desert, Tuareg music, such as that of Ensemble Tartit, and the takamba music and dance of the Songhai people, these arts were not so much new discoveries as old friends. But the Songhai and Tuareg did have a few surprises in store. First, after completing a world tour, Tartit was in Mali for just a week before heading to DC, and as a few members had family matters to attend to, the group was somewhat reformulated for the Smithsonian festival.

This is fairly normal for musical groups among the nomadic Tuareg. Anyone who has seen Tartit or the Tuareg folk rock ensemble Tinariwen multiple times has probably noted that the lineup is rarely exactly the same. These groups function more as collectives with rotating memberships than as set acts with clearly defined personnel. Tartit's leader, Fadimata (a.k.a. Disco), was present. More than seven months pregnant, she nevertheless sang, ululated, played the womens' tinde drum and even danced gingerly during Tartit's many performances. Another singer, Fatime, brought along her 2-year-old daughter, who insisted on dancing onstage through most of the performances, and became quite a hit with audiences.

There were also new faces in Tartit's lineup, but the biggest surprise was the presence of Abdallah, the leader of Tinariwen. Floating membership is one thing, but for the leader of one group to turn up as a support player, quite unheralded, in another shows an impressive lack of ego. Abdallah mostly just sang, but each Tartit performance ended with a guitar song during which Abdallah and Issa Mohammed would strap on their acoustic guitars and the group's sound would morph to something rather like Tinariwen's.

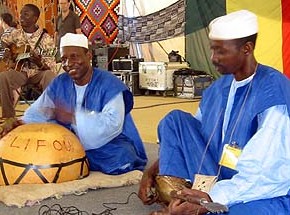

Songhai takamba music and dance were represented by a small, powerful ensemble called Baba Larab. This group was basically created for the festival in order to showcase the dancing of two of takamba's greatest exponents, Guilemikoye M'bara Ibrahim and Zéinaba Assoutor of Gao, a Niger River city east of Timbuktu, and the capital of the Songhai Empire during the 15th and 16th centuries. Baba Larab takes its name from Ibrahim's grandfather, a man who provided inspiration and support, although he was not himself a dancer. The takamba is a court dance, generally performed for nobility. It features slow, undulating movements of the shoulders and arms, and rolling eyes reminiscent of the sexually suggestive dancing one might find in a Congolese pop music performance.

That's not all that was suggestive in this performance. Ibrahim and Zéinaba danced the takamba both in the classical manner--sitting down--and in the more free-wheeling standing rendition that has emerged in recent years. Either way, the sense of flirtation and sensual delight was overwhelming. Ibrahim would wiggle his bare foot in the region of Zéinaba's breasts, or even touch her there briefly and then turn to the audience with a mischievous expression of glee. My co-presenter, Malian professor Cherif Keita of Carlton College in Northfield, Minnesota, wondered aloud whether these dancers ever had problems with religious authorities in the region. Northern Mali in general adheres to a more strict and conservative interpretation of Islam than one finds in the south, but clearly, this has had little restraining effect on these two fabulous dancers.

Equally impressive were the two musicians. With heavy rings on his fingers, Salif Maiga slapped and clicked on an enormous calabash creating the determined, pendulous beat that drives the takamba. Somehow, the dry extremes of the desert region generate conditions for the growing of particularly huge gourds, but even by these standards, Maiga's instruments were outstanding. An open handed slap on the top of the gourd--some players use a closed fist--naturally produces a deep, full sound, which if amplified correctly, has all the force of a bass drum, and Maiga's bird-bath-sized calabash could boom with the best of them. The clacking of his rings around the rim completed the sound, providing a fine example of one of the world's most versatile and efficient percussion instruments.

Yacouba Arawaidou played a small, three-stringed spike lute that the Songhai call kurubu. The kurubu is one of many such lutes in Mali, and these instruments were of particular interest at the festival because they represent precursors of the American banjo, one of the most common instruments found in the Appalachia exhibit just down the way on the Mall. It's difficult to say how many Americans are aware of this history, but when banjo players get the chance to observe one of these spike lutes in action with its drum body--as opposed to the box body on a guitar or mandolin--its high drone string in the thumb position as on a 5-string banjo, and its claw-hammer picking technique, they begin to understand.

Through quirks of cultural history, the banjo has mostly ended up in white musicians' hands these days, all but obscuring the instrument's African origins. But on the Mall, the connections were there to be made. One Malian musician who lives in Washington, DC, Cheikh Hamala Diabate, plays the Mande spike lute called n'goni. After years of living on the cusp of Malian music and old time and bluegrass, he has become fascinated with this bit of musical history. One evening, I found him in a hotel room accompanying two Bambara ngoni players using his "gourd banjo," an instrument made to resemble the first American banjos. This instrument bridges this all-but-buried cultural gap, and the resulting music was fascinating.

Coming back to Baba Larab, Yacouba Arawaidou was probably the most impressive spike lute musician at the festival. He picks with his thumb and a forefinger with a hooked, plastic finger pick attached to it. His instrument has only three strings--some have as many as seven--but the density of melody and rhythm he was able to produce was nothing short of stunning. Maiga and Arawaidou were truly a two-man orchestra. Arawaidou had the ability to establish one rhythm and then cut sharply across it with a dense flurry of notes establishing an entirely new feel without losing the first one, all with two fingers and three strings. As it happened, Arawaidou spoke neither English, nor French, nor even Bambara, so even with Cherif Keita's assistance, I could not really interview him. But I did learn that he comes from Gao and that he took up the kurubu after his older brother, a great player, died.

For his part, Maiga normally performs with the group Super Onze, a grand takamba outfit that performed on the last night of the Festival in the Desert this past January, just before Ali Farka Toure. Maiga was the only musician in Baba Larab to have attended that festival. There were some great dancers there, but nothing quite on the level of Ibrahim and Zéinaba. Sometimes on the Mall, they were able to coax audience members to come forward and try out some takamba moves. People tended to be shy at first, but once they experienced the pleasure of making those slow, graceful moves, smooth and gradual as the shifting of dunes in the desert, they easily got hooked. Before long, even children were swaying and gesturing and rolling their eyes in the subtle, sweet manner of the Songhai.

On the day after Oumou Sangare performed at the festival, her young guitarist Baba Salah dropped by the Bamako Stage during Baba Larab's set. Salah is from Gao himself and I was happy to have a guitar handy for him to play. He quickly fit into the music, skillfully intertwining Arawaidou's lines, and then singing a couple of his own songs in a silky tenor voice. Salah has at last released his own album and it's currently a hit in Mali, a landmark in Songhai pop music there. He gave Afropop Worldwide a copy, and it will be featured on an upcoming program.