Mark LeVine is a professor of history at University of California, Irvine, and Lund University in Sweden. He’s a specialist on the Middle East and North Africa and the author of the farsighted 2008 book, Heavy Metal Islam, which previewed the “Arab Spring” with its unpacking of social media organizing savvy on the part of underground musicians in places like Cairo and Tunis. Mark has been an Afropop Worldwide Hip Deep scholar, assisting in our work in Egypt, Lebanon, Ghana and Mali. His recent work has focused on Nigeria and Kenya, and he accompanied and assisted Sean Barlow and Banning Eyre during 2017 field work in Port Harcourt and Ogoniland. At the end of the trip, Banning sat down with Mark in Lagos for a debriefing. Here’s an edited transcript of their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Where to begin? Maybe a comment on Nigeria as a whole.

Mark LeVine: Well, I think when you go back to the beginning, it all went to hell in 1914 with the establishment of the Nigerian state. Unfortunately, like most every country from Morocco to Pakistan or even India, Nigeria is a creation of colonial border-making that had less than nothing to do with the natural geography, or natural human geography, or interest of the people who lived there. The creation of nation states that have their own institutional will to survival—will to power, so to speak—makes it almost impossible to change the borders. And we see what's happened with South Sudan when, in a contemporary situation, we try to change these borders, but wind up producing extremely dysfunctional states.

And wars.

Wars, and societies that are very weak. I don't mean the people are weak or the communities are weak, but the societies, the institutional commingling of various communities into one polity never had the chance to work because they were set up to fail, to ensure that the former colonial powers and the elites maintain the vast majority of these countries' wealth and strategic power. So these are all countries, including Nigeria, that were set up to fail. So when you think about Nigeria being the biggest country in Africa, almost 200 million people, living through at least one genocide, the Biafran war, whatever side you're on—10, 15 times worse than Syria is today, to put it in perspective—the fact that you have a functioning country and a city like Lagos that is always on the verge of chaos yet never actually falls into chaos and manages to produce such vibrant culture is miraculous.

You make that seem like a towering achievement.

It is a towering achievement. As messed up as things are, Nigeria manages to cohere. People live their lives, go to schools, get degrees. It could be in far worse shape than it is, and that’s thanks to the Nigerian people. They have produced a dominant culture, not just in Africa but globally.

Lagos street (All photos by Banning Eyre)

And yet in the travels we've now made to different regions of Nigeria, we’ve seen such diversity. There are still Biafrans who would like to hive off and create their own country, and in the north, it kind of feels like it already is another country.

Kano, in the northwest, is very different, although there are many southerners who live in the north and many northerners who live in the south, even here in Lagos. So it's not as cut and dried as two completely separate places. But let's remember: yes, Nigeria is obviously divided for all these historical reasons. Biafrans might well leave if they could, and certainly they tried, but the United States is equally divided in many ways. People from New York and California have very little in common with Middle America or people who voted for Trump. They never visit those places, don't know much about those places, and vice versa.

That's interesting. When we spoke with Fubara Tokwibiye at Chicoco Radio in Port Harcourt, he said that if there was a referendum in Nigeria’s southern and eastern regions: “Would you like to separate and create the country that the Biafrans attempted to create in the late '60s?” it would win easily. Maybe you could just explain to our listeners why that will never happen.

Well, it will never happen because the vast majority of Nigeria's oil is in the Niger Delta, so Nigeria is a state where the economy is dependent on oil production and to pull that out of the country's GDP would be a blow to the GDP that it would be in the near term almost impossible to recover from. Other industries or exports were never developed in all these decades because the country has produced and sold well over half a trillion or 600-plus billion dollars worth of petroleum. As many people have told us, this country was created to produce oil for export, and to make sure that no one group in Nigeria could attain enough power to remove government control of the oil sector.

No one would let Biafra “go” because that would take the most important source of revenue from the country. That might actually be a good thing in the long run, as we know. The oil curse can be so much worse than whatever benefits it brings. But in the near term, the state simply couldn't function without the amount of wealth that it derives from the oil sector.

Map showing the planned but never won Republic of Biafra

So no imaginable Nigerian government of any stripe would ever allow such a referendum to happen. And if there was another war, the outcome probably wouldn't be much different than it was in the 1960s.

I think it would be worse now because the south simply doesn't have access to weapons. Biafra was a recognized secession movement that had many allies in the Third World. It was a cause célèbre all over the world. That simply wouldn't happen today, especially after what's happened to South Sudan. Its independence is a cautionary tale; no one wants another South Sudan. A new Biafran War would be almost unimaginable in what it would unleash all across West, Central, and East Africa. It would make Syria look like a small border dispute.

And yet when I asked Fubara what will happen now, he just said “the killing will continue.” But he wasn't talking about war. He was talking about a kind of management killing, the sort Michael Uwemedimo and his people at Chicoco have so vividly documented. How would you describe the killing that's going on in the southern part of the country today?

Well, relatively speaking, we're talking about Biafra where two, three million people were killed, whether starved to death or massacred. So this is one of the biggest genocides of the 20th century. Bigger than the Armenian genocide to be sure. Somewhere between the Armenian and the Jewish genocides, bigger than Cambodia. It's really an unimaginable scale that is hidden now, because we can't see it unless you go into the jungles and see ruins of tanks or airplanes, which still dot it. But almost three million dead in the space of three years in a relatively small area, with a much smaller population than say, Syria, has today. We don't know what that means to experience something like that because none of us in our lifetimes in Europe or in the U.S.—I mean look what happened to us after three thousand people were killed on 911. It led to essentially a 15-year world war.

Compared to that scale, the routine killings you are talking about, which are horrible, are different. On the other hand, our friend Kunle Tejuosho from the Jazz Hole here in Lagos pointed out, the Nigerian forces today are far more vicious than they were in Fela's time. Killing is now a way to discipline a recalcitrant population and let them know the limits of their dissent.

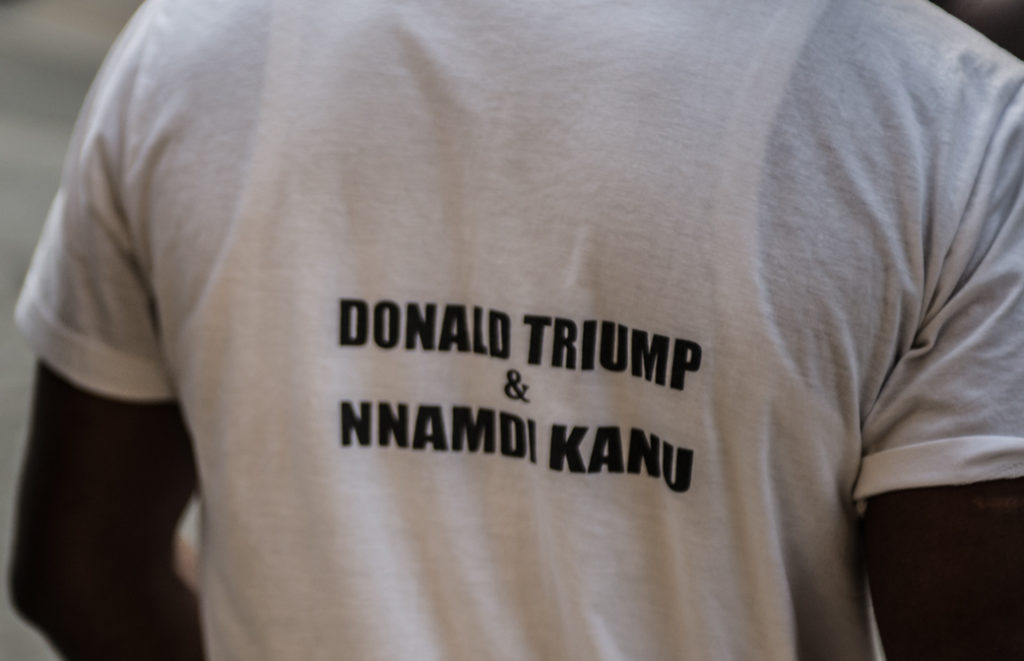

And yet, we have this interesting, somewhat bizarre situation on January 20 as Donald Trump was being inaugurated. There were two big protests we know of in Nigeria, one anti-Trump in Lagos, and one pro-Trump by Biafran activists in Port Harcourt. Maybe you can just explain what happened in each case.

Well, from what we can gather there was a far bigger pro-Trump demonstration by the Biafrans in Port Harcourt than the anti-Trump one that happened in Lagos. The government did nothing to stop the anti-Trump protest, but they shot and killed people—it's hard to know how many—at the pro-Trump rally in Port Harcourt. But I think the issue is not that it was for or against Trump. It was just Biafrans coming together to protest collectively, and this is automatically an existential threat to the Nigerian government. I think if it had been reversed in terms of support for Trump, it would've been the same thing. The issue was not Trump, because the Nigerian government in many ways has similar interests to the Biafrans in supporting Trump because of his willingness to go to war against Boko Haram. It's just that any assertion of a single voice by Biafrans is never going to be tolerated by the Nigerian government.

T-shirt from pro-Trump Biafra rally linking him with jailed Biafra activist Nnamdi Kanu

You and I visited Ogoniland to see how musicians are responding to a situation of environmental catastrophe caused by oil exploration. Maybe you could give us a little bit of the background. Let’s go back a little bit and talk about what actually happened in Ogoniland starting the late '50s.

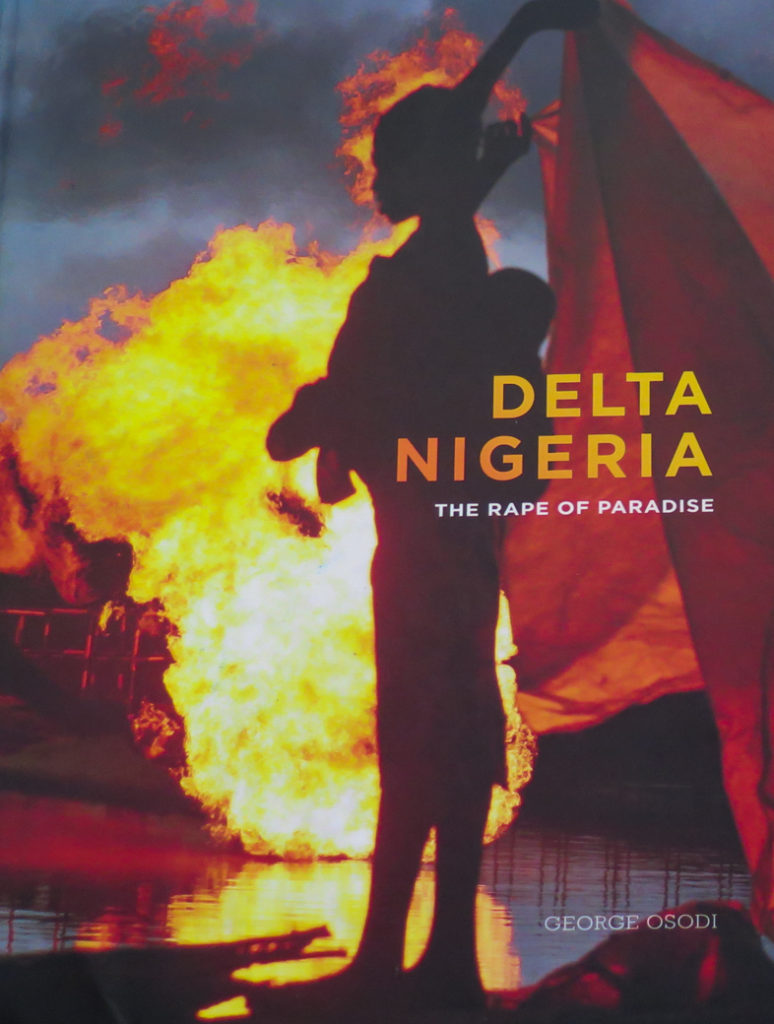

Ogoniland is a territory along the Niger Delta that has been inhabited since since time immemorial, as people like to say, although in this case it's most likely true. These were strong traditional communities with vibrant cultures, and the river supplied everything. These were fishermen and farmers, they had industry, as we saw when we visited Chief Eric Dooh in the ruins of his father's house. They were making their living from the forest and the river, and from agriculture, but they also had industry they were trying to modernize themselves. And they could have. But then the oil industry came, and almost no care was given to the environmental consequences.

The pipelines that move through Ogoniland and all the wells that were pumped in that region routinely spilled, and over the decades this had a tremendously negative impact on the river and the larger environment. The Niger Delta was one of the most diverse and important bio-systems on earth. It's on par—or was on par—with the Amazon. We would never see that now, because the vast majority of it is simply gone. It's hard to imagine the scale of that tragedy. The spills came steadily, and then in the mid-2000s—2004 and again in 2009—there were massive spills that essentially wiped out a large section of the river and all the territory surrounding it. We are talking a scale that most of us in Europe or the U.S. simply can't fathom, because it would never be allowed to get that bad. If we think about the Exxon Valdez or the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf, this is many orders of magnitude worse and it just went on and on and on and on. To the point where you have dozens of miles of river where the oil and the toxins go 13 feet or more below the bottom of the riverbed—not to mention deep into the shores of the river. All this earth is now completely toxic.

The mangroves were destroyed. You can't drink the water. You can't eat the fish...

Everything is so toxic there. The yams that grow there are toxic. The fish are poisonous. Think about that moment near the end of our time there, where an old woman walked into the water up to her waist, about 30 feet out into the river, and she was trying to fish. She was going to eat whatever fish were there, because that was all she could eat. She'd rather be poisoned slowly than starve.

Fishing woman, Ogoniland

We're focusing on the musical response in this program. It's interesting to compare the Chicoco artists we met on the waterfront in Port Harcourt, who come from pretty rough and desperate situations themselves, and the ones up in Ogoniland only a short drive away. They're both interested in hip-hop because it's an engaged art form. But there is a big difference between them. The people we met at Chicoco were exceptional individuals, so confident, so good at telling their stories, whereas the ones in Ogoniland seemed more tentative. Some were quite shy and not all that good at telling their stories. Maybe it's a language issue, maybe it's just how devastated they are and how cut off from the rest of Nigeria. What do you make of it?

I think you're exactly right. They're cut off. However devastated Port Harcourt’s waterfront communities are, it is still a major colonial city. It has an infrastructure that functions, however badly. When you get 60-70 miles out into the Delta, you're getting to far more marginalized areas—and you know, these people weren't marginalized by accident. They had to be marginalized because the only way an extractive petroleum sector could run at that scale of profitability would be if the environmental impact didn't have any cost to the company, so that none of the profits would have to be shared with the local people.

In Port Harcourt, we heard the departing minister of environment being interviewed on the radio. She spoke optimistically about the U.N.'s reclamation and clean-up program. She made it sound like everybody was rallying around these disenfranchised communities of Ogoniland and they were going to fix everything and make it right.

[Laughs]....Right. I mean what are you even supposed to say to that? Of course they can't. If you just do the math, with the amount of earth that would have to be moved to clean this place. First of all, it would be an entire different geography if you dug out as much earth as you'd have to dig out to reclaim or to clean it to soak it up. You're talking dozens of years and tens of billions of dollars. There's certainly enough money out there. Again, the petroleum sector in Nigeria has generated $600 billion over the years, so enough wealth has been generated to pay for this clean up multiple times over. But they won't.

The minister did say it would take 25 years.

That’s 25 years if they actually funded it and started it, but the government and Shell simply cannot fix this, because to do that would mean they'd have to accept a level of accountability that would have to go for the entire country. And in order to do that you'd have to have a completely different state, one that wasn't a renter kleptocracy. It would have to be a true democracy that represented all the people. So it’s not a question of technology or lack of scientific ability; it's a lack of political will by those who have power because they would have to give up literally unknowable amounts of wealth that they've been allowed to sequester from the petroleum sector.

Michael Uwemedimo of Chicoco Radio also made the point that if Shell were to step up to the plate in the Delta, it would be a problem for the oil industry worldwide, because that would mean Chevron would have to do the same in Ecuador, and Exxon Mobil would have to do the same in Siberia, and the list goes on.

Right. But sticking with Nigeria, we need to understand that there are two Shells at play. There's international Shell and there's Nigeria Shell, the local subsidiary. Activists in Ogoniland and elsewhere have told me the problem is less Shell International—which can in fact pay out billions of dollars without actually feeling it much—as it is Shell Nigeria and the Nigerian government, which is the majority stakeholder. But this government is essentially a huge kleptocracy, so powerful individuals have been stealing this wealth for a long time.

People think, “If only we could compel the big bad corporations to fix the mess they've created the world would be a better place.” That's true to a certain extent. But none of these multinational corporations act alone. This is how slavery worked too. We would never have had slavery if there weren't Africans who sold other Africans into slavery and created very powerful states for several centuries by doing so. In the same way we wouldn't have this disaster now if there weren't elites in Nigeria making this extremely damaging political economy work so well for so long. The Ogoni people are not just fighting Shell, they're fighting Shell and the Nigerian government.

The most important example of how brilliantly the government can manipulate things is how the government reached an agreement with the so-called “pirates” of the Niger Delta—the militants who were kidnapping lots of oil workers and tapping the lines. At a certain point, the government decided it was cheaper to pay them off and a lot of these big militants or pirates basically changed from their fatigues into nice suits went and bought nice homes on the outside of Abuja, and lived like kings there now. They've left the Delta. But all the boys that they ran so to speak suddenly were without income, without patronage and now they’ve kind of taken over perhaps as Chief Eric Dooh mentioned in conjunction with the aid of officials from Shell Nigeria, to continue tapping in an even more environmentally destructive manner the lines that were left open or tapping the pipelines that run through Ogoniland, taking it out on barges, what they call “bunkering,” and selling it on the open market where it goes throughout West Africa and, as some claim, all the way to Europe. This is a problem whose complexity defies any kind of easy solution.

Chief Eric Dooh at the site of his a ruined fish breeding pond.

The Ogoniland journalist/activist we interviewed, Alloy Kenom, said that music might be the strongest tool they have. And Chief Dooh said if he won his settlement, the first thing he would do is build a recording studio for his artists. Are they thinking that working on music is a desirable substitute for being tappers and bunkerers? Or do they have some larger belief in the power of music to deliver a message?

Both. And I don't think you can separate them. Giving young people skills and employment is crucial to any kind of development, but at the same time, these are cultures where music has traditionally been the way people have communicated with power. In the traditional communities that today comprise Nigeria, musicians were the one group that no one could touch. They were like the fool, the jester, the trickster, the ones who were allowed to speak truth to the chief, the king or the leaders of the community. When the community got too out of line or too powerful or were treating their people too harshly or unfairly, it was the musicians who spoke to them and they couldn't touch them because if they did there would be a revolt. It’s quite interesting that even though someone like Fela was beaten and tortured and imprisoned, he still wasn't killed. He was allowed to act even though they tried to punish him. Whereas someone like Ken Saro-Wiwa was framed and then hung for having an impact that was arguably no more important than Fela's.

[Mark goes online and reads about the environmental reclamation efforts.]

So this is from June 1, 2016. “U.N. hopes one-billion-dollar operation will boost employment and development in the Delta. A fisherman displays his meager catch from a creek near Goy, in Ogoniland. The effort to clean up one of the world's most polluted regions will be officially launched on Thursday by the Nigerian president. It will be a full 18 months before core remedial work starts…” Of course it hasn't started anywhere at all. “According to the agreement in Abuja, 200 million will be spent annually for five years to clean up the devastated 1,000 square miles region and river state near Port Harcourt. More money may be needed to restore the plan devised by U.N. engineers, oil companies and the government will involve building a factory for processing and cleaning thousands of tons of contaminated soil. There also will be mass replanting of mangroves. Many young Ogoni will be offered jobs. The intention, says U.N.E.P., the environmental program, is not just to clean up the region, which was once a center of production in the early days of Nigeria oil, but to create a task force of Ogoni people to clean up many other devastated areas of the Delta, the worst-affected villages from the spill in 2009…” The cleanup follows a 2006 request to the U.N. for a scientific investigation, the U.N.E.P. report of 2011, which showed shocking levels of pollution, 41 sites.

God bless the U.N.

One point five million Ogonis are among the only known people to have ejected an oil company because of pollution, led by writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. Shell was declared persona non grata by the movement survivors of the Ogonis people in 1993 and forced out of the region. Saro-Wiwa and other activists were executed in 1995 by the regime of Sani Abacha.

Mark, Banning, Chief Dooh, Alloy Khenom and Ogoniland artists

An incredibly provocative move.

So if you look at the United Nations environmental program report from 2011, it talks about a quarter-century or more of cleanup, but the budget for that cleanup, which according to reports is around a billion dollars is so woefully inadequate that it makes the report laughable. Because, you think about how much it cost to deal with Deepwater Horizon, which again was out in the ocean, or the Exxon Valdez, right? Think of the damage they did miles out in the ocean, to the shore, and then imagine dozens of sites where far more oil is contaminating directly for years and years without being stopped. So a billion dollars, even if they put through that much money, it wouldn't even be the beginning of what would be necessary to actually clean it up. So in that case the best you could hope for is a woefully inadequate job, which doesn't really do anything, especially when you consider at least 30-40 percent of that money will be stolen. That's the level of corruption. The graft will take it out at the international level as well as the local level.

Which is why I think the most important thing I always see when I'm there is the initiative of the local people. The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, as The Guardian pointed out, is one of the few indigenous communities that actually pushed out an oil company from their region because of how much it devastated that region. So if any good happens it will because the people just continued fighting despite the odds. As far as music, well, what else are they going to do? There's also an Ogoni film industry, which is shooting films depicting some of these issues, so it's not just music. It's culture more broadly.

But a film is a much more complicated thing to do than music. Novels and poetry are wonderful and people like Ken Saro-Wiwa wrote amazing things that educated so many people in the world about it. But that's not necessarily as relevant to the direct communication between people and power. Music is direct communication, there's no mediation.

MC Kay, rapping by a polluted creek.

The pop music coming out of Lagos is super successful, but not particularly engaged with issues, and that’s a big contrast to much of the music we’ve found in the Delta. What would you say about that as a historian looking at culture?

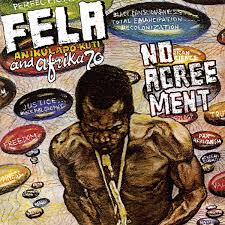

It’s not surprising that the vast majority of commercial music is apolitical, because commercial music serves a very different function than political music. I've heard young Nigerians say that as they read Fela Kuti's lyrics, they get really inspired, but even the rhythms don't move the kids today the way much faster and more pumping Naija pop or Afrobeats do today. Fela was in the '70s. The Nigerian state was still only a decade and a half old. It was still a state that was in formation. People were trying to understand what it meant to be Nigerian. It was right after a genocide that the army had undertaken in the Biafran War, it was hugely expensive and dislocating, and at the same moment a huge amount of oil wealth came in as well. So the direct political statements that Fela was making were necessary at that point. He was helping educate people and give them a voice.

I don't think anyone today needs to be told how corrupt the country is, or all the environmental problems in Ogoniland or any of the other myriad problems. Everyone knows about it. So if music is merely serving as the CNN of the streets, then it's a story that's already been repeated.

So for someone to come out and sing “Another song about corruption”… Maybe once every three years, someone does a song and it becomes a decent hit like Femi or 2Face or Seun. But I think that's why in a place like Lagos, which is very cosmopolitan and developed, that kind of music can seem almost condescending, like: “Don't treat us like idiots. We already know what's going on. We just want to have a good time despite that.”

And in a way what that's saying is “We can't change this, so at least let us try to have a good time to the extent we can.” I think that's where a place like Port Harcourt or Ogoniland, which are at a far lower level of political development perhaps than Lagos today, for them, that function is still important because they're still trying to create cohesive senses of community, that could then speak in a united way to the power of the government and any other forces that are oppressing them. In that sense, message music is more important in those communities than in a place like Lagos, where people have “been there and done that.”

Ogoniland musician T-Pen singing in the ruins of Chief Dooh's former family home.

So the target for these more engaged arts in the Delta states is their local government, not so much the federal government or the world, right?

I think you're exactly right. For example, when we saw Afropolitan Vibes at Freedom Park, Ade Bantu is one of the most political rappers in the country, and artists more generally, and he has songs even on his new album directly taking on these issues. His audience already knows this and I don't know that those kind of songs will mobilize people any more than they already are mobilized. I think where his kind of music can really have an impact are in places like Ogoniland or Port Harcourt where he can inspire the young people to develop the skills and courage to take on their government and the oil companies and other forces that are holding them down.

But this isn't just music. I have been in Port Harcourt and looked at children's theater, where you have people as young as 6 years old who were acting, actually encouraged to write their own plays in their own words and speaking out about the trials and tribulations of having to work on the street selling things. You know, these street sellers who are in every crowded intersection in a place like Port Harcourt, and how much abuse they suffer. Young people are using theater to educate their parents who have allowed them to be forced to go out and work in such a dangerous and ruthless situation from the time they're little. So you see it in music, you see it in community theater, you see it in art, you see it in these mini film industries that exist in Ogoniland. So music is part of a broader movement of culture in Nigeria that in certain locations can become highly political.

Let's remember that in Africa and also the Arab world, poetry and oral traditions have been far more powerful to the present day than they were in Europe or North America where other communication media developed. So it's not surprising that hip-hop, which is obviously the most poetic medium of popular music we've ever had, would become so taken up by people who wanted to use music to make political messages. The question to me is, how many times can you make the same message? Yes, we can sing another song about Shell, but why is anyone going to care? Whereas people in Port Harcourt or Ogoniland still want to hear that message because the music mobilizes them in a way that people in Lagos are not going to be mobilized.

Maybe we like to criticize singers and rappers anywhere who aren't political, given the problems facing the world. But maybe they know something we don't. Maybe they know that to their audience, saying the words we would like them to say doesn’t mean a whole lot.

Port Harcourt religious billboard, a constant presence

I'd like to get you to address the subject of religious diversity of Nigeria.

It's far less diverse now, sadly, than it was a century and more ago. As in Ghana, there was always Islam in the north. For centuries. Really, until the coming of the British, Christianity was a marginal religion. Certainly, the Portuguese had been in West Africa for far longer, and there were parts like Congo that already had their kings converted to Christianity four centuries earlier, but traditional religion was far, far a bigger percentage of the population in both Ghana and Nigeria, even a few decades ago. It's less diverse now. You have two competing camps that have consolidated. Both have crowded out as completely illegitimate any other form of religious practice and also have enough money and wealth to distribute to get more people into schools and services and then the ideology that goes along with it. So you kind of have Christianity and Islam facing off in Nigeria, but there was once an incredible variety of religious traditions in this country that have more or less disappeared, at least from public view.

They've gone underground.

They've gone underground and I think that's a disaster because these traditional religious practices and beliefs were part of communal structures that had been developed over centuries. These were practices that encouraged decentralization, communal versus state power, all things that no government was going to want to encourage. Christianity and Islam, each in their own way, represented civilizing missions. So traditional practitioners were constantly being berated by Christian leaders and also by Muslim leaders. This is something that Fela addressed when he spoke directly against Christianity and Islam and specifically saw himself as a high priest trying to bring people back towards what he thought of as traditional Nigerian or African religious practices. Those practices were more in tune with the earth, which was being massively destroyed right at the time he became political in the '70s when the oil business took off and more and more was flowing and the environmental degradation started to tick up. So it's all very organically related.

Crowd at Port Harcourt megachurch

That's interesting. Of course, it’s hard for us to gauge the amount of traditional religion that remains. We see little hints of it here and there, but it's clearly been stigmatized. In terms of Christianity and Islam, looking at the three cities we visited—Port Harcourt, Lagos and Kano—what strikes me is how much Christianity has become commercialized. Practically every single billboard in Port Harcourt and, to a lesser degree, Lagos, is advertising some kind of Christian pastor, church, revival retreat, five days of glory, 12 days of revelation, two days of power, just everywhere. Whereas up in Kano, a totally Islamic city every bit as religiously engaged, with the call to prayer happening constantly and everyone praying regularly, we saw zero sort of commercial manifestation of the faith. It's just an interesting contrast.

Well, they have very different political economies. Again, Islam has been here a lot longer than the kind of Christianity we're seeing here and Christianity has changed dramatically in Africa in the same way it has in Latin America. We're used to having the Catholic Church or Anglican Church, especially in Nigeria. Now you have the redeeming churches, the various Pentecostal and evangelical-style churches which have become far more powerful. These churches bring with them a very specific politics and a very specific economy. And it's an economy that is based on this imagination of self-help, of pulling yourself up, all of which makes sense if you live in a place where you know the government and no one else will ever help you. So the ideology underlying these churches that have become so powerful certainly makes sense in this context, but they're also hyper-commercialized because that's the way they compete with each other. It is a business.

You went in to one of these megachurches and saw a pile of money that looked like some video shot by the D.E.A. when they had a huge raid on one of the major drug barons in Colombia or something. I mean that's the kind of cash that moves around here every week in these churches. So it's a huge business and they compete with each other and that's part of what attracts people: the fact that their religion can be monetized. Nigerians famously love to monetize everything because they're always hustling to somehow make a little bit more to pay their daily rent and wages and keep their families in food. So the monetization of religion is an investment. When these people pay out all this money to this church they're not doing this just because they're foolish or brainwashed, they're doing this because they're calculating that instrumentally being involved in the church giving this money opens up all kinds of networks—schools for their kids, potential jobs, potential scholarships, social networks to take care of them if anything happens. So there is a huge economy there.

Counting cash at a Port Harcourt megachurch

The structure in the north is very different. It’s much older, and very traditional. Up there, the newer kind of Islam that you see in Egypt with the Muslim Brotherhood or the televangelists, that kind of Islam has not really reached this area of the Sahel, whether it's Ghana or Burkina Faso or Nigeria. It's either the more traditional versions of Islamic practice or the more militant Salafi version. And that has its own monetization, but it's obviously a far more destructive one, not one that's going to be on billboards. But let's remember anywhere where they take over, all of a sudden, you do see billboards. They advertise too. If you go to an ISIS town or somewhere like that. Once they're in power they advertise too, they communicate the same way.

A great moment in our Hip Deep in the Niger Delta comes when you bring Fela Kuti’s song “No Agreement” to the young artists at Chicoco in Port Harcourt, and they start spontaneously singing and rapping over it. Tell us about your Fela project.

Well, the story starts in Tahrir Square, I think on the third anniversary of the Egyptian revolution, when I was sitting in the apartment of Ramy Essam, someone you guys met and interviewed back in 2013. This was after Sisi took over as president, and Ramy actually said to a few of us who were sitting there watching it on TV—because he literally couldn’t leave the house or else he'd be lynched—he said, “It's like watching zombies.” And of course anyone says zombie to me the first thing I think of is the song “Zombie” by Fela. And I said, Oh yeah, like “Zombie” by Fela. And he looked at me like “Who?” And it just occurred to me: you're the singer of the revolution and you don't know who Fela is? That had to be corrected. So we pulled up “Zombie” and I showed him the lyrics and told him, “You have to do a version of this song. That's what Egypt needs right now. It needs an Arab Fela.”

And he's like “Yeah, that's true.” So at that moment we started conspiring to create a version of “Zombie” that he would write new lyrics to and sing in Arabic. But then I know so many Arab revolutionary artists that I thought, why not get people from all over the Arab world? Because what Fela was singing about 30-40 years ago, is utterly relevant in the Arab world today. So that became the genesis of this kind of “Arab Fela” project. Take his most famous songs, keep the original groove and chorus perhaps, but rewrite lyrics on the same theme. So if its “Water No Get Enemy,” Lord knows water is a big issue, let “Lady” talk about women, and “Shuffering and Shmiling” talk about all the ways people face humiliation. “Shakara,” which we did with Songhoy Blues in Mali and Femi in Nigeria, talks about how people try to present themselves as being far more powerful than they are. So what we've been doing in Port Harcourt is “No Agreement.” The refusal of people to agree to be exploited, humiliated and repressed anymore. And as we saw in Port Harcourt, once young people hear the lyrics, wherever they are, they get it immediately. Because he still makes sense.

So the project became a way to take these revolutionary artists, often quite young, and introduce them to the most important political artist of the 20th century, within African and Arab contexts. So we started with “Zombie” and got people from five countries, and Seun Kuti was part of it and that got released by the organization Freemuse, which is the global anti-musical censorship organization. It became kind of an anthem for Music Freedom Day and several of the artists went to Norway and above the Arctic Circle to perform in Harstad in March 2016. And then we did “Shakara” with Songhoy Blues and many of the greatest traditional Malian musicians when we were in Bamako last year. That recording continued to progress over a year on three or four different continents. Femi did a wonderful sax solo on it. Now we're doing “No Agreement” with the young people in Port Harcourt and there's going to be a second version in Turkana in Kenya, also very marginalized communities that are now just about to suffer the problems of having a major oil industry begin in their communities. So we're now connecting the young people from Turkana and Port Harcourt. Once again, Fela is a way to create new relationships, as he's always been.

Mark LeVine and Michael Uwemedimo

There was a great moment in our interview with Michael Uwemedimo of the Chicoco organization where he talked about his discovery of the importance of music, in part thanks to you. He was talking about demonstrations in Port Harcourt against forced evictions. Here’s that exchange:

Michael Uwemedimo: If you look at the videos of the demonstrations, you started seeing that music was important in the action. It was a lot of music. There was a lot of singing. And we started thinking about the relationship between musicmaking and movement building. Then Mark came along. First of all he just visited. He opened the door and he got hit by a wave of music. And Mark said, "O, this is great..”

Mark: I said, “I have a song. Would you like to record on it?” And they said, “Sure, what is it?” “Fela Kuti.” And I think half the kids were like, "Who is Fela Kuti?” “You need to know who Fela Kuti is, and here is the song.” And they started singing the first take. Literally one taking 20 minutes, they just came up with this incredible chorus, new chorus, and they were just singing about their lives and it was beautiful.

That makes for a great moment in our program. Anyway this is a powerful concept and delivering terrific results. Do you have a catchy title for this project?

Fela Lives?

That's good.

I don't know. But you're asking a damn good question. Originally it was the Arab Fela Project but now it's gone so far beyond that.

Maybe we should hold a contest.

Hold that thought.

Thanks, Mark. A great conversation as always.

The promise of Port Harcourt...