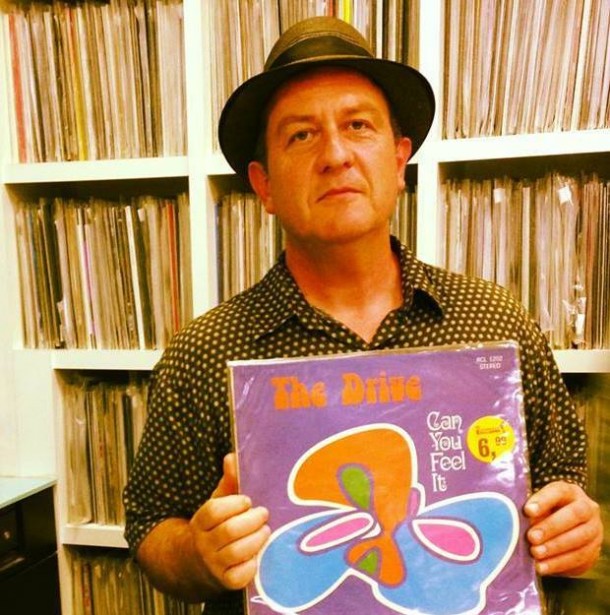

Matt Temple is the founder of Matsuli Music, a boutique record label which specializes in vinyl reissues of rare and classic South African Afro-jazz albums. As part of the research for our radio show on the vinyl reissue market, Reissued: African Vinyl in the 21st Century, producer Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar spoke to Matt on the phone from his home in London. Matt also made an exclusive mix of '70s Afro-jazz for us - stream it above or on our Soundcloud.

Alejandro Van Zandt-Escobar: How did you get started with Matsuli Music? What motivated you to launch a record label?

Matt Temple: I established the label, Matsuli Music, in 2010, and the idea was really born out of my background in music promotion and also being a music enthusiast. And it was in the context of people like Russ Dewbury, who issued what I would call the first Afro-funk compilation, called Afro or maybe even Afro-funk, back in '97-98. And then you had the Nigeria 70 compilation from Strut, and subsequent to that you had Analog Africa. So there were a lot of labels that were starting to reissue African music and recontextualize it, and given my background growing up in South Africa and being involved in the promotion of music in South Africa whilst I was at university, I saw that there were a lot of South African jazz recordings, specifically from the '70s, which had gone out of print, and the only way in which you could get hold of them was to pay very high prices on eBay or Discogs. Given the fact that there was a new audience listening to the stuff that Strut and Analog Africa were starting to put out, it seemed as though there was an opportunity for a label that could focus on South African jazz and popular music from the '70s, and so I started the label in 2010. The first issue we did was Dick Khoza’s Chapita album, and since then we’ve put out eight LPs—we are specifically focused on vinyl—and about two years ago the label introduced a new partner, so I have a new partner in the label, a guy called Chris Albertyn who’s based in South Africa. So, for the last two years, we’ve been running the label together, which works very well with me being in London and with access to production facilities here, and with Chris being in South Africa dealing with a lot of the licensing as well as the distribution into the South African market, which, in the last couple of years, has seen a big resurgence in listening to music on vinyl per se.

Why do you release music on vinyl?

I think vinyl is an enduring format, in the sense that vinyl has outlasted cassettes, it’s outlasted CDs, and it seems to be … it’s got more gravitas than digital versions of music. Whilst digital versions of music are very convenient for us to have on the move, if you are what I would call a serious music enthusiast—and that’s how I grew up, I used to go for listening sessions with my friends to go and listen to what vinyl albums they had—there’s a sense in which it has gravitas. It’s something tangible, and I think the artwork and the physical dedication that you need to actually go to a record shelf, pull out a record, put it onto a turntable and put the needle onto the record means that you’re having to spend time listening to something as opposed to something which is just part of the background ambience. Anyone can just fire up a Spotify playlist and stream it through their house, but you know, on one level that’s not really listening.

Is there a big market for your vinyl records in South Africa?

Well, I’ve always kept my eye open to places that sell vinyl in South Africa, but if you can judge the resurgence of vinyl by the number of shops that are selling vinyl … before 2010 you would only really find vinyl in second hand stores or antique stores or charity shops, and certainly in 2010 there were maybe one or two dedicated vinyl stores in South Africa, whereas now you’ve got at least one to two vinyl stores in Durban—which is a large center in KwaZulu-Natal—in Johannesburg you’ve got three to four dedicated vinyl stores and in Capetown as well. There are definitely more people buying, so in much the same way as consumers in Japan, North America, Europe and elsewhere in the world are preferring to purchase vinyl and have vinyl to listen to, that same trend is replicated in South Africa.

How would you say the market compares to the markets in Europe or North America?

Well, I suppose it’s very difficult to compare the markets. I think it’s true to say that the largest market for our label does tend to be Europe and North America and probably a demographic that is not gonna change that much. I would say that only 15 to 20 percent of our sales are in South Africa itself, and if you had to compare that with Strut or Analog Africa, you probably would say that it’s a little bit different. And I think each of the labels have got different trajectories. If you look at Analog Africa, Sammy [Ben Redjeb, the owner of Analog Africa], has been all about compilations as opposed to original albums, in the same way that Strut and Soundway certainly kicked off very much in the compilation mode and trying to access what I would call a tropical dance-floor audience, specifically focusing on West African Afro-funk as their entry-point to capture the market. As they’ve progressed, so they’ve gotten into much deeper areas. For example Soundway has started to issue original albums and they’ve also started to look at slightly different genres of music, moving away from Afro-funk per se. You know, the latest Soundway compilation is all disco and Afro-boogie. So I think each label has a slightly different trajectory. If I look at Matsuli Music, we’ve dedicated ourselves primarily to issuing original albums, which probably change hands for very high prices in second-hand markets. So we haven’t done any compilations and that remains our mission although our trajectory can probably, in the next couple of years, take in new music—I mean we’ve been speaking to a lot of younger musicians who we may find place for on the label in terms of new music coming out of South Africa, and also from the compilation perspective, there’s a lot of music which was originally issued on 78s in South Africa and which has never really been issued into the marketplace, so those are areas that we will probably start to explore.

A lot of the albums that we’ve reissued, just because of their scarcity, are highly regarded in South Africa and people want them, which is why, as I was saying, 15 to 20 percent of our sales are in South Africa. So, you know, if you had to compare that to another African country like Zimbabwe or Kenya or Nigeria ...I think in that sense Matsuli Music is slightly different, because I don’t see the reissues of Ethiopian music that Heavenly Sweetness have put out on vinyl as finding 20 percent of their sales in Ethiopia. And I can't for a moment imagine that Soundway or Strut are selling 20 percent of their Nigeria compilations in Nigeria. I could be wrong, I could be wrong, but I think there is something different.

What is the process like when you're reissuing an album?

Typically when we’re planning releases—we’re governed as I said by wanting to reissue original albums which are out of print and which are currently commanding high prices within the second-hand market—we’ll typically try and identify who the master recording rights reside with. I think for us we’ve been fairly lucky because of quite a few of the albums that we have reissued were recorded by one particular individual who ran a label in South Africa called "As-Shams" or "The Sun", and his name is Rashid Vally. He was very influential in providing the recording time as well as the sales outlet of his record store called Kohinoor to artists who he recorded and whose LPs he packaged up and then sold. So he probably had a catalogue of about 30 to 50 original albums, of which we’ve reissued a several—the Chapita album was his, the Sathima Bea Benjamin album was his, the Black Disco album was his. He also had acquired the rights to the Batsumi album, so a lot of the master rights were sitting with him and he is thankfully still alive, and we were able to get the legalities of that sorted out fairly quickly.

When it comes to the compositional rights, again, where we have been able to contact the owners we’ve had a very positive response. For example, with the Batsumi albums, the leader of the band is this guy called Johnny Mothopeng, and when we were able to make our first payments to him he was overwhelmed by the amount of money that he was receiving from us compared to what he received back in 1974 when he did the original album. So I think there is a lot of good will, and that same good will is evident in some of the other artists who we worked with. For example, with Tete Mmambia—we reissued his album by the Soul Jazzmen, with Pops Mohamed—who composed and performed the Black Disco album—and also with Sathima Bea Benjamin. I mean, essentially what I’m trying to say is we try and do absolutely the right thing in terms of who the legal earners are, irrespective of what the history may have been. That’s not to say that … you know, we run the label part time, so sometimes licensing can take a lot of time to get right. At the moment, probably 80 to 90 percent of the master rights of all recorded work in South Africa resides with the Gallo Record Company. There are a number of recordings that we have tried to license but have been very difficult for us, because of their, shall we say, ambitious claims to ownership and exaggerated ideas of how much money we make from this business. So I suppose what I’m trying to say is that there are still a lot of recordings that we would love to issue but that remain in the vaults because of licensing problems.

How have you seen your reissues impact the musicians or other people involved in these recordings, such as Rashid Vally?

I think for Rashid Vally, who is now a retired guy who was involved in music from the age of 18 through to the age of 55 or even 60, it was wonderful that there was a new generation rediscovering the music. He certainly wasn’t going to do it for free, but he was very excited by the fact that there was a new audience rediscovering the music. I suppose with people like Pops Mohamed and Johnny Mothopeng, again, a surprise that people were interested.

From the label’s perspective, our most successful release has been the Batsumi album which was the second release we put out, and we’ve repressed that a number of times. Certainly amongst the vinyl collectors and musicians in South Africa, that has started to grow new roots. There are a number of new bands who are taking inspiration from hearing those recordings from the '70s, and I’ll cite for example a band called The Brother Moves On. They perform and compose their own music, but when they came to London, they did an evening where they did renditions from the Batsumi songbook. There’s another group that is on another reissue label called Nyami Nyami Records. They call themselves BCUC. If you listen to their sound it’s very much in the same vein as that Batsumi album. There’s another group in South Africa called The Sun Xa Experiment. Again, they will do renditions of Batsumi songs within their sets. So, in a way, there’s a cross-pollination between times which has kind of fed off the reissues that we’ve done. So, that’s very encouraging to see.

So who in South Africa is listening to this music? Are you reaching a wide audience?

Well, we need to be realistic. The biggest and most popular music in South Africa is gospel music, probably followed from a popular perspective by South African house music. One shouldn’t inflate the interest in this music as being beyond … you know, it’s not a sizeable audience that are interested in this, but what’s encouraging for me is that it has reached certain people. For me, the power of music is all about transcendence, in the sense that jazz in South Africa was a transcendence of daily conditions, and a lot of the music that we've reissued was born in the heat of very difficult social conditions. And whether it was about protest overtly, or it was about having a good time, it was about creating a space where you could transcend some of those social conditions and when you see music transcending like that again, and speaking to people of new generations ... as the label co-owner, that puts a big smile on my face.

Tell us more about yourself. How did connect with this music growing up in South Africa?

So I grew up in South Africa as a privileged white kid, probably realized something wasn’t quite right when I was a teenager. I was fortunate enough to go to university, and in 1982 I attended a cultural workers symposium in Botswana called "Culture and Resistance," where a lot of the exiled musicians were playing and there was a call to people involved in culture to start using culture as a way of influencing social opinion in South Africa. So whilst at university, focusing very much on indigenous artists, be they the likes of Malombo, or reggae groups, and various others, I was involved in promoting those on the university campus. Later, in 1985, I left South Africa to avoid military service and was in London from 1986 onwards, running an anticonscription organization which was aligned to the ANC in London.

Do you see any parallels between your reissue work now and your activism-charged music promotion work at that time?

No, I think the world has changed completely. Those times were pre-Internet and we were in the midst of a struggle that was transcending into a civil war between the anti-apartheid forces and the military government of P. W. Botha, so very different conditions. I think we now live in a very different world, and we’re all consumers now. We’re all part of big brother’s generation. They’re tracking us on our mobiles, they can enable listening on our devices, they’re farming our data … resistance is futile. But, having said all of that, music still retains an element of power in terms of transcendence, either on a personal level or on a social level. I think reissuing music doesn’t for one moment compare. I certainly don’t have ambitions of doing anything as grand as that. I think if I compare reissuing music now to promoting concerts back in the day, there was a much grander agenda back then because we had to try and defeat an apartheid government and we were looking to find whatever ways we could to influence that struggle. Nowadays, I suppose if I look at the mission of the label it’s the fight against forgetting. I want to remember work that was done in the '70s by artists, and by reissuing them we’re bringing them back into prominence and we’re saying, "these guys made important work, let’s not forget it." And at the same time, pay a fair compensation for the work, which they may never have received back in those times.

August 1974. Maswaswe Mothopeng and Thabang Masemola of Batsumi give a live performance. © Sunday Times/Times Media

August 1974. Maswaswe Mothopeng and Thabang Masemola of Batsumi give a live performance. © Sunday Times/Times Media

You described your mission as the "fight against forgetting." How do you see the work of a reissue label connecting to that of archivists?

I certainly support the idea of archives but I suppose the question is, “Who uses them?” The music was made in a social context and I’m not sure in much the same way that the music that we produce needs to sit in a library or an archive ... it does need to be listened to, it does need to be enjoyed. Having said all of that, certainly, on a personal level, I think there’s a lot of work currently taking place in South Africa to try and at least build a record of what was there. I think the problem with archives unfortunately is that you’re left collecting physical artifacts, and the physical artifact represents only a small subset of what actually transpired at the time. So one of the projects that my label partner was involved with was a book called Keeping Time, and this documented photographs and live recordings made by an individual during the '60s and '70s in South Africa. I supposed what I’m trying to say is if you only focus on the physical artifacts that were left behind, you may have a skewed representation of that past, and you’ll never relive that past. Archives are an important way of signposting what was there, but for me it’s not the most important thing.

You've mentioned a few different reissue labels that have been doing this work for many years now. In terms of your trajectory, are there any labels that stand out in terms of inspiring you to launch a label or showing an example of how this work could be done?

The first reissue label that I came into contact with was called Earthworks, which was run by a guy called Jumbo Vanrenen, and reissued a lot of South African and Zimbabwean music in the height of the “world music” period. There were other labels then like Globestyle and Triple Earth and a couple of others. But certainly Earthworks, in terms of what it curated, what it presented, and the attention that it paid to the graphics, stuck in my mind. The next that really came to mind for me was a reggae reissue label called Blood & Fire. They started in the mid-'90s and they were in a sense reissuing classic Jamaican reggae and re-presenting it to a new audience. So again, the combination of what music they selected to reissue, together with attention to the graphic representation as well as new contextual notes—liner notes—are all very important and they follow through to how we work as a label now. We’re very careful about what music we put onto the label, we’re very careful about the artwork that we commission, and we’re very careful about the contextual notes that we put into place. And then, obviously, if you look at work from the likes of Analog Africa and Strut and Soundway, again, similar sort of ethos around care and attention to what they’re presenting.

You know, I suppose what frustrates me is that the reissue market is starting to get fairly crowded, and I don’t know how sustainable it is. I do typically purchase most of the reissues, certainly African reissues that are out there. I do get frustrated when something is poorly designed, poorly packaged, and with no contextual liner notes. The label’s argument is that the music speaks for itself but I suppose I do fetish the actual object as much as the music. So, you know, if I’m buying something that’s going to stay in my house, it should look good, it should give me a little bit of idea of what the context is, as well as care and attention being paid to the sound remastering and the pressing. Those are all very important.

Thank you Matt!