Mdou Moctar is a Tuareg guitarist and singer/songwriter from Niger. He has been touring in the United States in support of his third album, Sousoume Tamachek. It’s a beautiful, intimate session, blending acoustic and electric guitar, male voices and light percussion, essentially on the reflective, folky side of Tuareg music. As Mdou explained in conversation with Banning Eyre before his recent concert at the Lincoln Center Atrium in New York, this is the “desert blues” side of his repertoire. He also has a rock side, as he and his two accompanists amply demonstrated in a rich, wide-ranging show that had the chock-full space enraptured. Here’s Mdou’s conversation with Banning.

Banning: It is a great pleasure to meet you. To start, is this your first visit to New York?

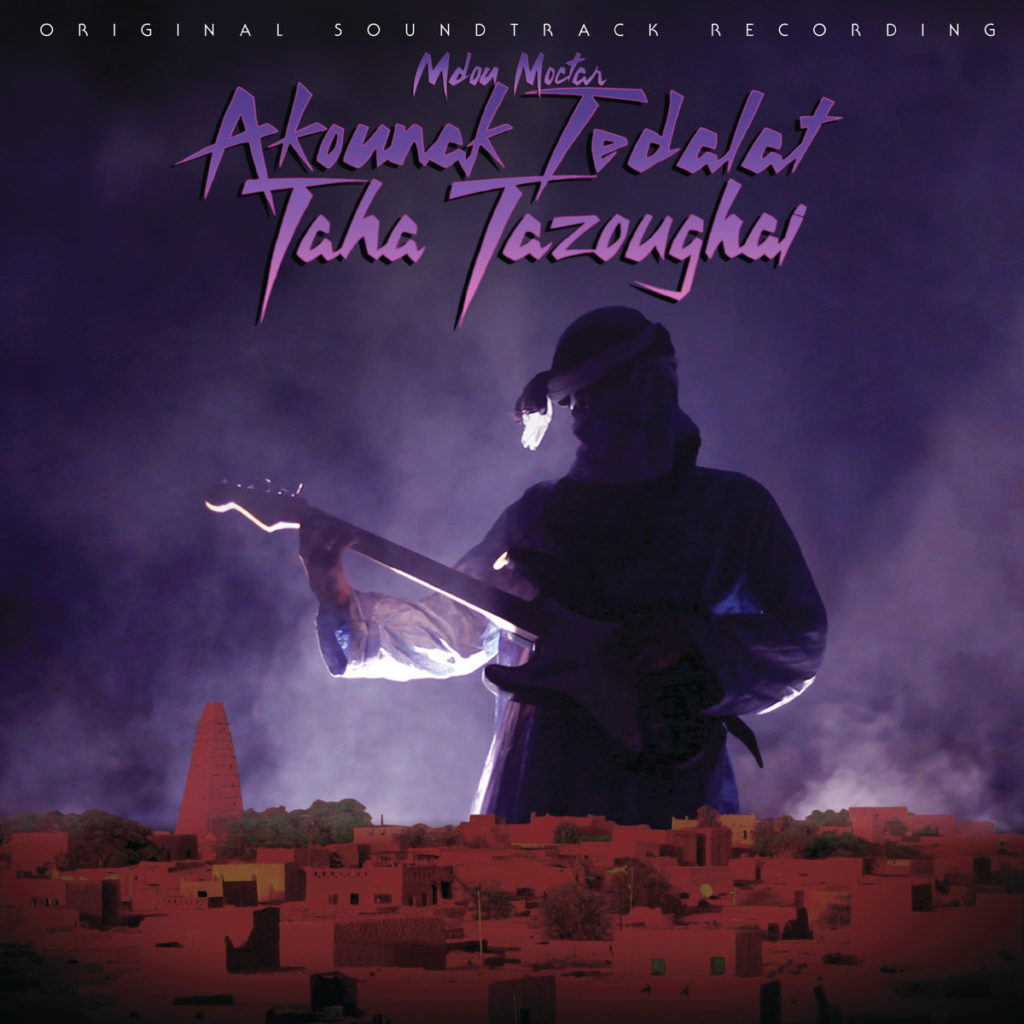

No. It’s my second time. But the first time was for a screening of the film Akounak Tedalat Taha Tazoughai (Rain the Color Blue, With a Little Red in it). It was not for music. This time, it’s for music, so it’s very different.

I’ve heard about this film. Describe it.

Is a very interesting film. It’s as if we did a remake of the film by Prince, Purple Rain. It was the first time for me to be an actor in a film, and I was pleased to have the opportunity. It great for me to become an actor. It was also a way for me to recount something of my musical story, my musical life.

How was the film received in Niger?

It was very well received in Niger. People really liked it. It is actually the first Tuareg language film, so people really appreciated that. And what’s impressive is that the original Purple Rain film was made in 1984, the year I was born. Also, the week our film was released was Prince’s birthday. So these are kind of magical things. It’s too bad that Prince never got a chance to see the film. He had left us by then. I really wanted to meet him, and it’s too bad that never happened.

Very sad.

Yes. Very sad. But that’s the way it happened.

Before making the film, were you familiar with Prince’s music?

I didn’t know the music of Prince in my childhood. But what really touched me is that we have almost the same story.

How so?

Concerning his private life, it’s as if he made the film and it’s almost the same life as mine, considering the problems I had in my life. The histories are similar. We just added a few things.

Tell me about your history. You were born in a village, right?

Yes, in Tchintabaraden. And the significance of this word in Tamashek is “the town of beautiful girls.” That’s what it means. My name Mdou [pronounced EM-doo] is an abbreviation of my name Mahamadou.

Got it. So in the village when you were young, what was your life like? How did you get introduced to music?

I didn’t stay in the village for long when I was young. I traveled to a place near Arlit with my mother. So then I stayed there, and it was there I did my primary school, up to college. So I really grew up Arlit, near Agadez. That’s where I met an older musician called Abdala Inbadougou, and became interested in being an artist.

When were you born?

1986.

So your childhood coincided with the first modern Tuareg groups, especially Tinariwen, were first emerging. Is that right?

Yes. Ever since I was young, I heard that music on cassettes, but I did not know the artists. The only artist I knew by name was Abdala Inbadougou, who was a very famous in our area. Abdala Inbadougou had started in Tinariwen, with Abdallah Catastrophe [Abdallah Ag Alhousseyni]. This group was called Desert Rebels.

Interesting. we’ve known those guys for about 15 years. But you grew up with that music.

Yes. I grew up with that music, and there was a young person who played it at that time, a younger artist named Koudédé, and after him came Moli. I grew up listening to their music as well, but I was very young.

What other kinds of music did you listen to on cassette? Or on the radio?

I loved Farka Touré. I also like traditional music, especially takamba. This music pleases me deeply. I’ve always kept that taste, that rhythm of music, even if it’s influenced by a few modern elements, it has to always stay within the same taste. This is one side of my music. Because I play two different kinds of music. I play some music that is more rock, and then I play desert blues.

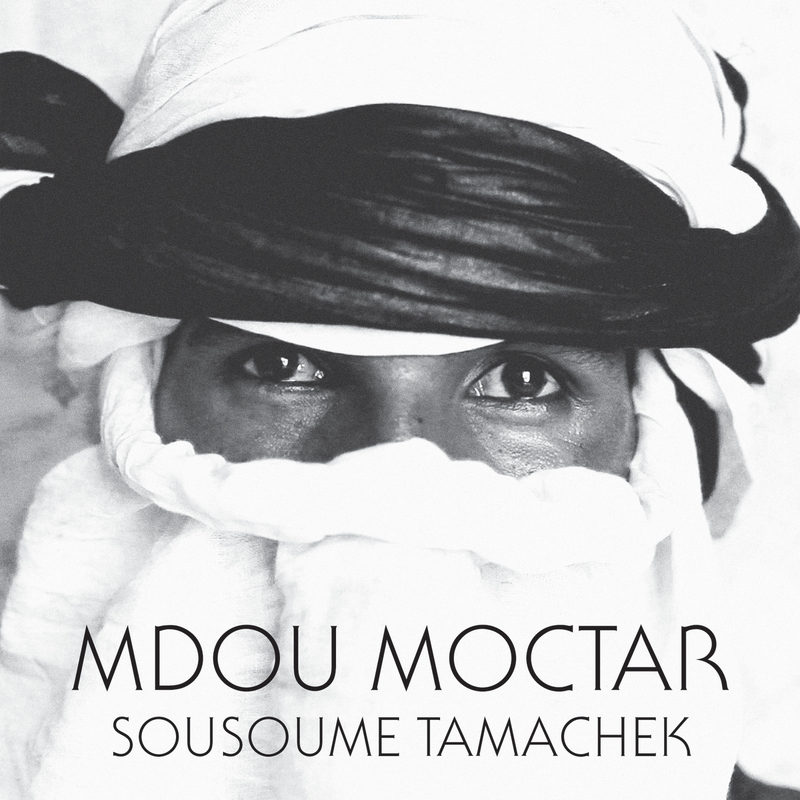

Interesting. So the new record, Sousoume Tamachek, that would be more desert blues, right?

This is my beginning in music. This is like my first foray. These are the songs I made when I was young. I never had done them in the studio. I never had a chance. So I took advantage of the chance to bring them back, to bring back my youth, the things that passed in my youth. So this is a very rich. These are very different songs, with very strong messages. This is an album that talks about the revolution, religion and love. Revolution, religion and love.

Interesting. Where did you record this?

In Portland, Oregon. With Chris. But not in his house, in a studio.

Tell me about the title, Sousoume Tamachek.

Sousoume tamashek is something you say when a person is sad. You might tell them to quiet down. Calm down. It’s like we would say in English, we would say this in Tamashek. “I know you have problems. I see that you are crying.” I would be trying to calm her down with these words. Calm yourself. Why is she crying? Because our land has been divided during the time of colonization, right up to the present. It’s not finished. But I’m talking about the past. People were divided—some in Algeria, some in Libya, some in Mali. So we didn’t have a homeland. And now there is all the suffering that takes place in the desert. We don’t have nice houses. We don’t have hospitals and schools. Our children are not well educated. There’s so much suffering.

But despite all that, our land has a deep soul, even if that soul has been exploited. We are not recognized in Mali, as Malian citizens. We do not have proper consideration. And this is also true in Niger. Even in Algeria. Even in Libya. It’s not as it should be. So we have all these difficulties that have happened to us. This is why we had rebellion. The idea was that the world would come to help us after all this. But instead, people have come to divide us.

Especially after the troubles in 2012, with the rebellion in Mali.

Yes, yes. All of that as well. This is what I say in the song “Sousoume Tamachek.” We are orphans of three countries: Mali, Niger, Algeria. This is what’s behind the title of this album.

Mdou dancing takamba at the Lincoln Center Atrium (Eyre 2017)

I understand. That is powerful. I want to ask you about one song that I particularly like, “Tanzaka.”

“Tanzaka” talks about religion. As I’ve just told you, this album is very diverse. It talks about three things: revolution like the title song, religion, and also love. So this song is a song about religion. “Tanzaka” is like sleeping from eight in the evening until 11 o’clock in the morning. You sleep and sleep. But you must get up. You must pray and work. This is what builds a man. Life is not about sleeping. When you wake up, if there are problems, you must face them. Homelessness. Poverty. But you’re just sleeping. You must wake up, dress yourself, wash and work. So this is the advice I give in this song.

You’re trying to encourage people not to give in to hopelessness.

Yes. Yes. You must get up and work. You should not be sleeping in. Then there is the song “Ilmouloud,” another song about religion. The mouloud is like the birthday of the prophet. So I am talking about the values in our religion, tracing lineages back to him. I’m explaining his importance. This kind of thing.

O.K. Tell me about one of the love songs. You pick.

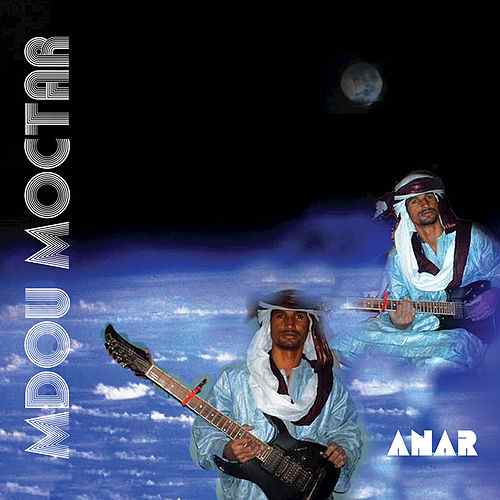

Well, for example “Anar,” the first song. Anar means eyebrows. This is the name of my album from 2008. But I played this song in a different way on this album. It’s a sensitive song for me, full of memory. Because it’s a composition I wrote when I was very young. I speak about a lot of things in it. I’m speaking to my girlfriend, telling her how I love her. When I pass the night with her, the night becomes very short because we are together. It passes so quickly for me. The whole night becomes like a single hour of time. And afterwards during the day, when I am not with her, I pass the whole day thinking about her.

Nice. So this is your third album.

Anar was very electric. My second album was a live album, Afelan. Then, there was the the soundtrack for the film. But for me personally, this is the third.

And it’s a more acoustic album. You are going back to your early songs.

Yes. When I was young, I composed many songs. But I never went to the studio. So when it came to making the album Anar, I had a lot of songs to choose from. So I just took eight out of some 20 songs and made that album. This time, I wanted to make a simpler album, a solo album, drawn from my early compositions.

Let’s talk guitar for a moment. How did you learn guitar?

When I was young, it was difficult for me. Because I was from a very religious family that really didn’t like music. They wanted me to go to school and complete my studies. I did my studies, and I learned the Koran. This is what was welcome in my family. But me, I was too interested in music. I liked the religious side, but it was very difficult for me to combine the two. Among us, there is a difficulty. It’s hard to be both a student and an artist. You’ve been in Africa. You’ve seen this. It is hard to do these two things. But I did it. I realized that I loved too much playing music too much. I couldn’t stop playing music.

I had no money to buy a guitar. And anyway, it was pretty much impossible to buy a guitar, so I made my own. I made my first guitar with my hands. By the time I had a chance to get a real guitar, I was growing up. I was 16. That’s when I got my first proper guitar. Afterwards, I had to travel. So I had to leave the guitar. My family told me that I was obliged to travel to earn money for the family. So I left in 2003 to work in Libya. I spent two years in Libya working. It was very difficult.

What sort of work did you do?

I was one of those young kids who drills to make wells for drinking water. You call these boreholes in English. I did this to the point of becoming an expert in it. I wound up in the town called Ouadane in Libya. And there, I met was a guitarist named Hadani. He was also from Niger, living in Libya and working. So one day there was a wedding, a Tuareg marriage. And it had been a long time since I had been among the Tuareg. I saw him playing, and wow! I found myself once again going crazy for the guitar. I had to buy a guitar.

So I did buy a guitar. I came back to the guitar. I played all the time. I left Libya. I went back to my home with my guitar and a little money. And then in 2005, I played, and played. And then in 2008, I made that first album.

Did you ever the traditional lute, the tehardant?

No. I never played the tehardant. Never. I love it, but I did not grow up with that. I did not grow up among artists like that.

So on guitar, did you have any teachers, any role models? How did you learn?

I really didn’t find people to help me. The problem is I’m left-handed. All the guitarists I knew played right-handed. Being left-handed made it very difficult. But I listened, I learned, little by little. And I started to get somewhere. I loved the guitar so much, I could not be discouraged. Even when I was not good. I worked. It was not unusual for me to spend the whole day playing. Even if it was just two notes, I would spend the whole day learning those two notes. I was just too interested.

So by the time you recorded in 2008, you had found your way. And did you play both acoustic and electric?

I did both. It wasn’t very difficult for me to change. I had spent so much time playing alone. In the beginning, it was a little strange with the electric, that big loud sound. But after a little while, it was O.K. My first electric guitar was given to me by an artist, Aroudeni. He’s in Niamey now. He gave me my first electric guitar.

So on this new album, you play both. A lot of the songs start with an acoustic guitar introduction, and then the electric comes in. You have a nice conversation between the two.

Yes. These are all my ideas. It’s a crazy thing. It’s like when I did my first album Anar, the Tuareg had never heard AutoTune. They never used that on their voices. So it was this electronic voice. But me, I had been listening to Hausa music from Nigeria. And I said, why not? Why can’t I try that in Tuareg music? I was curious. What would that sound like? So that’s why I did that. I decided I would just try it. It became something quite extraordinary for people. They really liked it. Really, really liked it. And of course after me, lots of people are now doing it.

Fascinating. We were in Kano earlier this year. And we were quite interested in that music with all the AutoTune in the voices. Have you ever been there?

I was in Kano when I was young, but it was not for music. But I presented my album in Sokoto, which was very far from me. I was young and didn’t have a lot of means, but I felt I had to seek things out.

So is that Hausa film music well known in Niger?

Oh yes, yes. Very well known. Very popular. Because there are a lot of Hausa in Niger.

It’s interesting. That music is very beautiful, but there is no guitar in it. Almost none.

Yes. Well. I don’t know what I can say about that. They’re not really instrumentalists. They play keyboards in the studio. And those people from Nigeria, they really don’t play live. It’s all background music for films. It’s playback. They really can’t do it live. So that’s a big difference between us and them. We play live.

We did meet one artist there, Ali Jita, who told us he was one of the only ones to play live with a band. He had two guitarists, but they were from Niger.

You see? That’s it.

So how did you meet Chris Kirkley and get hooked up with Sahelsounds?

Here’s the story of my connection to Chris Kirkley. In the beginning, he heard my music. He heard it while he was in Mali, and he asked people for my contact. People didn’t know where I was. Afterwards, he went to Mauritania and again he heard my music. By this time he was very interested. He wanted to release a compilation of artists from the Sahara. So eventually, he met an old man in Mali, and he could tell by his accent that he was from Niger. He was even from my region, Tahoua.

So now Christopher sent out a message by Facebook. And anyone he met with a guitar, he would ask, “Do you know Mdou Moctar?” Now me, I don’t look at Facebook very much. But afterwards, he found a friend, someone who lives in my same neighborhood. And he said he knew me. “Good. Very good. Have you got his contact?” “No I don’t have his contact, but I have the contact of his friend.” He gave Christopher the context of my friend. And he wrote to my friend on Facebook. My friend sent him my number. And one time when I went back to visit my birth village, and Christopher called me.

“Hello, I am an American,” he said with a very bizarre accent. “Hello, I am an American. I want to work with you. Your music really interests me.” With a very strange telephone number.

He had heard your first album?

Yes, he had heard a few songs from Anar. So I said, “O.K., I will give you my contacts.” He asked me to send him some music, but that was very difficult. The Internet connection is almost nothing. So I couldn’t send anything and after two or three weeks, he wrote me a message: “Listen, please, if this is not you, Mdou Moctar who I am looking for, please let me find him, because I want to work with him. Please don’t waste my time.”

So I wrote him right away and said, “Listen. It is me, Mdou Moctar. Please call me and I will show you.” So he called me and I took my acoustic guitar and played for him all the songs that he knew. He was very happy and very surprised, so that was how it started. Afterwards, he came and visited me and we started working together.

And was he the one who suggested that you work together on the film?

It was his idea, but after I told him my story, he remarked that it reminded him of the story in Purple Rain and he suggested that I might be the actor in the film he was planning. So it started like that.

A new fan dancing at Mdou’s Lincoln Center concert (Eyre 2017)

We were in Mali last year reporting on the history and music of the Tuareg people. It’s still a tough situation there in the wake of the 2012 rebellion. What’s your take on the situation today, in the region, but especially in Niger? By the way, I haven’t been to Niger yet.

Well, you will come. I will give you my contact and welcome you there.

Thanks very much. But what’s your take on the situation there?

Well, people are too caught up in their studies. The Tuareg are divided into two sections in Niger. There are the Tuareg of Azawad. That’s based out of Tahoua. Azawad includes Mali also, but the Azawad of Niger is not the same as the Azawad of Mali. And then there are the the Tuareg of Aïr. When we talk about Aïr, we’re talking about the region of Agadez. So the Tuareg are divided in Niger. Most of the Tuareg of Azawad, the great majority, are students. This is why I say they are too caught up in their studies. And they are politicians also.

Now when you talk about the Tuareg of Aïr, most of the youth are artists. Of course there are students as well, but not like in Azawad. And there are politicians too, but again, not like in Azawad. Do you see what I’m saying?

But the problems began in Aïr. This is the richest part of Niger, but also the least developed. There is a lot of unemployment. There are three factories there. Even four. But despite all that, it is not developed there. Not well built up. People are radiated by uranium. There are no good roads, no good work as there should be. It is things like this that make people become rebels and bandits. Because they see people taking the riches from under their very feet.

You’re talking about the mineral riches.

The mineral riches, yes. But when we say Tuareg, really, we are all the same. When you touch the Tuareg of Mali, you have touched the Tuareg of Niger. The countries may have borders, but we have no borders among us. The Tuareg are the Tuareg. This is what I’ve found. I don’t know. Maybe things will change in time, but it’s not easy. It’s not easy.

Mdou Moctar trio at Lincoln Center Atrium

Do you think music has a role in this evolution?

Yes, music is very important. It has brought about changes in my understanding. I am one of the artists who works a lot with youth, to help them, educate them, especially about music. My drummer is 23 years old, and my accompanist, Ahmoudou Madassane, is 25 years. He has been working on a film with Christopher Kirkley. It’s called Zerzura!. It came out recently. And the drummer too. He makes his living with music and he tours with me. And then Ahmoudou Madassane is also the manager of a women’s group from Azawad who are on tour, Les Filles de Illighadad. So music can rescue people from unemployment. It’s work. It’s a career for young people as well.

Thank you very much, Mdou. It’s a pleasure to meet you. The problems you face are deep, but you are right. Music is a powerful tool of resistance. Good luck with it.

Thank you.

For more on Mdou, including his 2017 tour dates, as well as the films and other artists mentioned in this interview, visit sahelsounds.com, a rich online source on the music of Niger and the entire Sahel region.

Ahmoudou Madassane