Meklit Hadero is a singer/songwriter now living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her fifth album, When the People Move, The Music Moves Too (Six Degrees) takes a deep dive into the music of her ancestral homeland, Ethiopia. Meklit is featured on the program, "With Feet in Both Worlds." Banning Eyre spoke with Meklit from her studio in San Francisco.

Banning Eyre: Meklit, Nice to see you again, via Skype. For our listeners, start by reintroducing yourself.

Meklit Hadero: My name is Meklit Hadero. I am an Ethiopian born, U.S. raised singer, composer and cultural instigator. I am trying on that word: “cultural instigator.” Basically, by that word, I mean I like to think about the way that music and culture can help us ask questions about who we are and where we want to go.

You were born in Ethiopia. How old were you when you came here?

I was just two years old when I came to the States. We actually spent a brief time in Germany between Ethiopia and here. I was in Germany for less than six months, and then D.C., Iowa, Brooklyn, Florida, New Haven, Seattle, San Francisco, lots of places along the way.

Quite a list. Over the years, we’ve seen you perform in different styles and settings.. This new record is the most engaged with Ethiopian music. But tell us about the journey that led there.

I started making music later than a lot of people do. I wrote my first song when I was 25 years old. But it was something that was deep in my heart, something that I’ve always wanted to do. But I didn’t really understand how you could do it in a meaningful way until I moved to the Bay Area when I was 24 years old. And as soon as I moved to the Bay Area, things started to go with music. I had waited so long to follow that passion that I felt like: I don’t care, I just need to go. There was an urgency to it, just a push: write songs, write songs, write songs!

My early songs were very much in the singer/songwriter style. I wrote my first song on the guitar a month after I started playing it, and I performed it like three days later. I really didn’t know what I was doing, but I had gotten a Young Musicians Scholarship to the Blue Bear School of American Music, and I took as many classes as I could. I just wanted to get this thing that was inside of me out into the world. So that meant melody, lyrics, and strummy, chunky chords. The songs I was writing were determined by the skill I had as a musician at the time, which was skeletal. But it was authentic to me, and it was deeply passionate. I wasn’t really thinking about what I wanted to sound like, so that kind of limitation ended up determining my sound.

That said, I have a lot of respect for singer/songwriters. That whole “three chords and the truth” thing. Sing your truth. I was also running the Red Poppy Art House at the time, and I knew all these jazz musicians. Jazz was such a big part of the music that I listened to and grew up on, and really took to my heart. It was just a powerful, powerful music. And I started bringing jazz musicians into this melody poetry, and strummy, chunky chord thing. And that was my early sound.

But you know, Ethiopian music was a big part of who I was and what I grew up hearing. I just took a while to integrate it all. I think what really allowed me to start integrating it to a different degree was, one, just growing as a musician and arranger overtime, and then also work that I did with Nile Project, which just completely immersed to me in East African music in a whole different way.

We’ll pick up right there with the Nile Project. But first, a couple of details. What year did you write your first song?

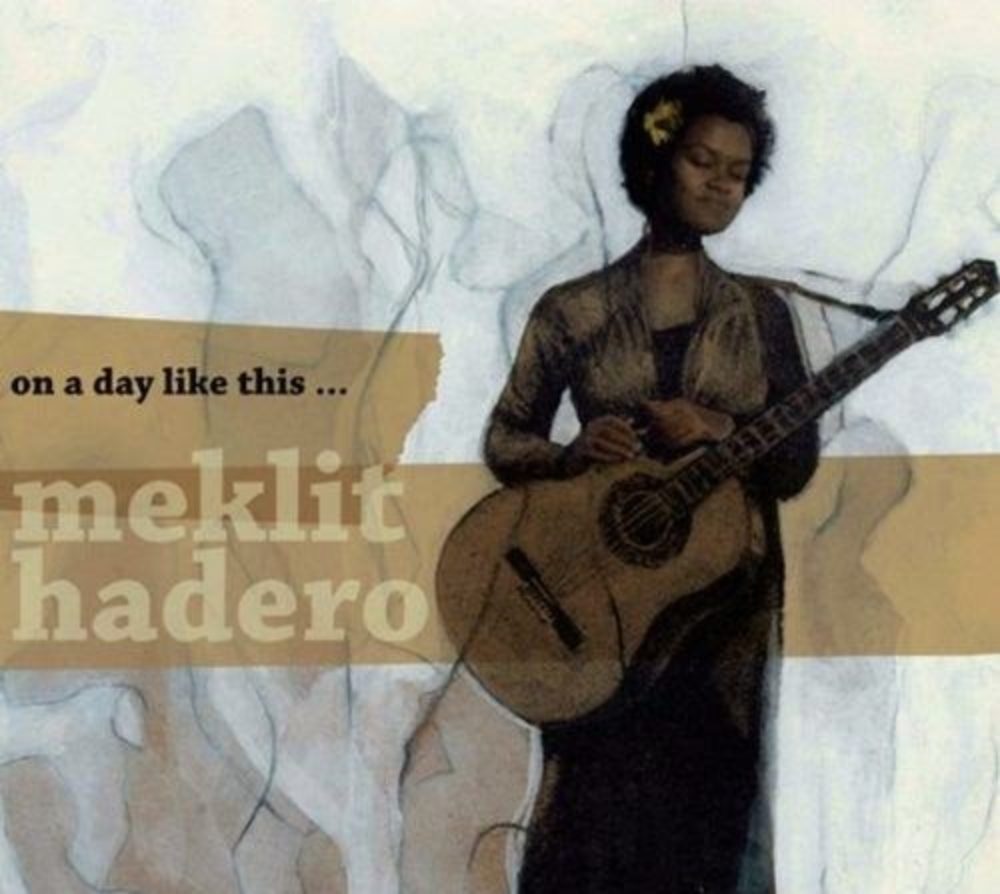

I wrote my first song in 2005. And I don’t think I wrote another song for eight more months. Then in 2006, they just started flowing. I put out an EP in the last days of 2007, and then my first solo album, On A Day Like This, came out in 2010.

So you weren’t writing songs to get that music scholarship. What was your musical life like up to that point?

Well, the Young Musicians Scholarship at Blue Bear was given annually to young musicians aged 12 to 25 to take classes at their school. It was really for early-stage musicians, but people who wanted to take music seriously. So I was in the last year of eligibility for the scholarship, and the photo for that year looks like I was the leader of a child band, because all the others scholarship recipients were like 14, 12, 17. It was funny, but I didn’t care. Whatever it takes.

So you were a singer before that?

Yes, I was a singer. I always sang. I grew up singing, casually and occasionally in school and organizations and functions, things like that.

Did you think that music was what you really wanted to focus on in your life?

It was something I had always wanted. I wanted to be a singer, but I didn’t understand how I could do it in a way that was meaningful. When I was young, I saw two paths, one that was really a cult of fame, which seemed superficial. I didn’t identify with the cult of fame. I didn’t want to do that. And then the other way I saw was people engaging in music in a very academic way: practice, practice, practice. And they kind of seemed miserable. And I thought, “But I love this.” Little did I know that I would later love to practice.

It’s hard to envision that in advance.

Yes. But I think when I came to the Bay Area, I became swept up in this community of musicians who are socially engaged. I was like, “Oh. This is meaningful. I can do this.” And from there, I gave myself permission to take music seriously, to really acknowledge and honor that force inside me that was saying my whole life: You should be a musician.

That’s wonderful. Now just before we launch into the Nile Project, I’d like to know about your home life when you were growing up with your parents. What kind of music did they listen to at home? Did you hear Ethiopian music? And what was the music that made you want to be a musician?

My first songs were lullabies. My mother would always sing Ethiopian lullabies for us. And she has such a beautiful voice. She’s not a professional singer, she doesn’t have that in her. But she always had such a beautiful, soothing voice. So the first music I loved, or lullabies. They were very tender. You know, the voice is close to your ear. You are sleepy and in that in-between world, and it just goes right into your heart.

Then the next music was… I have equal memories of old tapes of Ethiopian music and Michael Jackson. Those things would kind of go back and forth in my life in Iowa. We were always listening to Ethiopian music, always on tapes, never good quality. It was always that they had been played so many times that they would slow down and speed up and stretch the way tapes do. We would keep the tapes underneath the place in the car where you can hold beverages, so that beverages would like drip onto them. So there would be that one place where you would always hear that warp. But that was my childhood music, just going back and forth between ‘80s radio and Ethiopian music in the house.

Great. Now, let’s fast forward to the Nile Project. What did that experience do for you?

Well, as I say, I listened to a lot of Ethiopian music growing up, and then I didn’t listen to much in high school. And then in college, I started listening to it again, you know, in my early 20s. But I didn’t have a deep relationship, a daily relationship with Ethiopian music makers. Until the Nile Project. And that’s the difference I think, being around the instrumentalists.

Of course, I had dear friends, and I would visit to musicians, but it’s not the same as living a daily life for months on the road with people. Jorga Mesfin, who is the Ethio-jazz saxophonist on the Nile Project, is one of my closest friends in the world, and had been for a really long time. He really spent a lot of time with me teaching me what you might call Ethio-jazz theory, which kind of doesn’t exist anywhere. You can’t actually take that class. But he gave it. I mean, you can take it with Jorga, or you can take it with Samuel Yirga or with Mulatu Astatke. But you can’t actually study that at any university. You just have to be with the people. That’s it. There’s no other way to get that information. So we just spent so many hours together. And Dawit Seyoum would just put a krar in my hand and be like, “Look, it’s real simple.” He would just give me exercises and spend time on this instrument. He gave me my first krar.

So the first Nile Project residency was in 2013, and then we went on the U.S. tour in 2015, and we did two residencies in 2014. After that, I understood how to arrange in Ethio-jazz in just a whole different way.

And that’s what we hear on this new record.

Yes.

And it’s great. I find it interesting that you have managed to combine the sensibility of a singer/songwriter with the Ethio-jazz aesthetic. And it’s very comfortable—not an easy thing to do. This particularly struck me on your version of the song “You Got Me.”

Well, “You Got Me” is Erykah Badu and The Roots' hit from 1999. That song for me was really special, because when I was growing up in the States, the only images I ever saw reflected back to me from where I was from were about famine. It was this very one-sided narrative where you just felt so unrepresented out there. There was just nobody out there that was singing to me, except in hip-hop, occasionally in hip-hop with people like The Pharcyde. You know, “There she goes again. The dopest Ethiopian.” You would feel that. It would be like this bright light. “He’s talking to me. He’s talking to me.” It’s this moment where you feel seen and acknowledged. I don’t know if those artists understood what that meant to young Ethiopians, but I hear it everywhere I go. If you talk to the community, those words, that simple insertion of your name meant so much.

That’s something that I hope I can do for other people. So when Black Thought called my name in that song: “Ethiopian queen from Philly taking classes abroad.” I thought, “O.K., one day I need to do an interpretation of that song.” So it’s something I had been thinking about for about five years, but finally my skills and my sensibility caught up, and I understood how to do it. We totally remade the song. It’s a different melody. It’s a traditional rhythm. It’s in the scale of tizita minor. It has that beautiful Ethio-jazz solo by Randall Fisher by the band Ethio-Cali down in LA. And I do know that The Roots have heard it.

And I bet they dug it too. Maybe we should talk about the song that really gets directly at the theme we’re talking about here. “This Was Made Here.”

O.K. In 2014, I got a grant. I was commissioned by the Map Fund, this wonderful organization in New York, to create this music. And at the time I called it “This Was Made Here.” Later I changed the name of the body of work to” When the People Move, the Music Moves Too.” But originally, the name was “This Was Made Here.” The idea was that I wanted to make music that was so deeply American, and also deeply Ethiopian, that it could only be made on these shores In this time. And that’s what that title means. And it was a song that ended up really speaking to the longing of in between. It’s the song on the record that has the journey itself inside of it.

Tell me about the song “I Want to Sing For Them All.”

“I Want to Sing For Them All” is my anthem. Music can be very abstract. So I just wanted to tell people exactly what was going on, just make it as plain as day, as clear as light. This is what is going on in my history. This is where this music comes from. Let it not be a paragraph or page-long description. Let it be something you can groove to.

It’s a beautiful song. Let’s talk about “Human Animal.”

Cool. I’m glad you asked about that one. People don’t ask about it much. That’s my environmental anthem. “Human Animal.” The idea is we have to understand that we are part of nature and we can’t be separated from it. Instead, we want to say that we are better than nature, or apart from it. And I think that’s why we are in such big trouble. That’s why we have been able to do what we have to this environment. But we are nature. We are not separate from it. And I wanted to sing that in a way that felt nonacademic, to make something that was celebratory of that fact. So that’s what “Human Animal” is about.

Just one more “Memories of the Future.”

That song is about the way we can have these really strong visions of what we think the future is going to be like, and then they can be just busted by reality coming in heavy. And we have to reckon with that. We need to have our dreams, and our plans, and an idea of what we want the world to look like. We need that to guide us forward. But sometimes, boy, does it come from out of nowhere that we really only have part of the picture. As much as we want to understand where the future is going, we can never really have more than part of the picture. And so this song is about the moment where the pin bursts the balloon, and how difficult it is, but also how we have no choice but to reckon with things as they are.

That sounds like an apt description of where the country is now, at least for those of us who were expecting a very different scenario.

Yeah. But the thing is, I wrote that song from a very personal place, from personal experience, but then I saw that it was much bigger than that.

That can certainly happen. I think that’s the song musically that starts in one mode and then goes into a kind of Ethiopian chacacha rhythm. That’s very nice transition.

Thank you. Yes, the 6/8 comes in.

We love it. Now you have mentioned that the Bay Area was a very inspiring environment for you. What was it about this environment?

Well, the Bay Area really has a strong political history of resistance and leadership in the time of the Civil Rights movement. That is something that is very present in one’s experience of the Bay Area. We come from that history and when I moved here, the '60s and '70s era really loomed large in the way people went about things, and in the feeling of being here. Right now, you can argue that that’s changing with the way the tech world has affected the Bay Area. But when I moved here, that history felt very present, and artists were uniquely oriented toward social practice art, art that takes into account your community, city, social, political and historical context. So when I started to get immersed in that kind of dual understanding of artists and cultural activists, I just felt at home. Because I want my work, my music, to be meaningful in multiple ways. I want it to be something that people can dance to, and feel free to, and experience all kinds of emotional catharsis with. At the same time, I want to make music that points to healing, and to an acknowledgment of underrepresented voices, and that brings what might have been a hidden world out into the public sphere, into the public eye.

So I want my music to be able to exist at all these multiple levels, and the Bay Area, because of its history, has really encouraged that. Of course, many folks are suffering in all kinds of ways, all over the country and all over the world, around issues of gentrification, and here is like ground zero for that. There are a lot of artists who are struggling and suffering. So it’s a very different world from the Bay Area that I first came to. When I came here, the housing prices were still pretty low, because they were still bouncing back from the first dot-com crash in 2001. Now, the rents are so high that a lot of people have gone.

To wind up, let’s telescope out and talk about this idea of people with “hyphenated identities,” as you once put it, and the music they make. It seems there’s something new happening now with so much migration around the world, and generations of kids growing up in a culture that was not their parents' culture. What are your thoughts about this now, from the angle of music?

I feel like when you go to a country and ask someone, “Show me your culture,” they are going to show you their music. And of course they’ll show you other things. They will show you their music and their food. But this puts music at a kind of telescopic nexus. Culture is an elusive thing to define, but we can use music to talk about things that are hard to talk about. So when you ask somebody “Show me your culture,” music shows up. That’s one thing.

The second thing is we have never experienced as a globe the kinds of movements of people that we are in right now, and that we will see in the coming decades. We are going to get all kinds of climate-change refugees, and they are going to be coming from everywhere. And right now, of course we have seen the refugee crisis unfolding across the world. I think that in the process of people moving around the globe, what you realize is that no matter where they are coming from, they bring their music with them. In my mind, I see a box that you can carry with you, that has no weight and has no burden, so it can go whereever you go. So that’s the second thing.

The third thing is that as culture evolves, music evolves. I think that nobody has ever really been happy with the concept of “world music.” It was a marketing term. We know its history. It was concocted in a London pub in 1987. And it was kind of a small group of people’s best try and making Bob Marley as easy to find as King Sunny Adé and Paul Simon. So, yeah. We have a hard time grappling with this idea of world music, but what we can say is that our neighborhoods, communities, cities, and countries are going to get increasingly diverse. Things are going to bump up against each other and that means cultural shift. I think that we also have changing ideas about assimilation and integration. You know, in the past, in the United States, there was a push toward assimilation, where you just had to come into the mainstream American narrative and just forget the past. You know, America is very future oriented.

But I think that is changing. There seems right now to be an ability to stand in two worlds, and to accept that kind of complexity in culture and people. On the one hand, American music was born out of the forced migration of slavery—blues, jazz and hip-hop. We can’t forget that. But the way that the country is changing in its demographic is going to continue to shift the music. I think the distinctions between world music and American music are just going to start to blur. I think we are going to start seeing many different kinds of rhythms and social orientations come into what we call the mainstream. And I think that’s something that’s really exciting. We can’t know where things are going. But what we can say is that they ain’t going to stay the same. And there are going to be people from all over the world who are part of defining the future of our culture. And that includes the music that they make.

Nice. You’ve neatly summarized the mission of Afropop. We started in the beginning telling the stories of African music as a way of contextualizing and helping people understand American music in a fuller way. There was a time when people didn’t even really necessarily recognize the African origins of American folk music. Now it’s a cliché. But this whole new wave that’s happening now, people who come here voluntarily or as refugees or just through other circumstances and, as you say, bringing their culture with them, is exerting a new force on popular music. And I think that’s a key idea for all of our realities going forward. Thanks so much for this.

Thank you.

And we look forward to seeing you at the Apollo Theater Café on March 2.