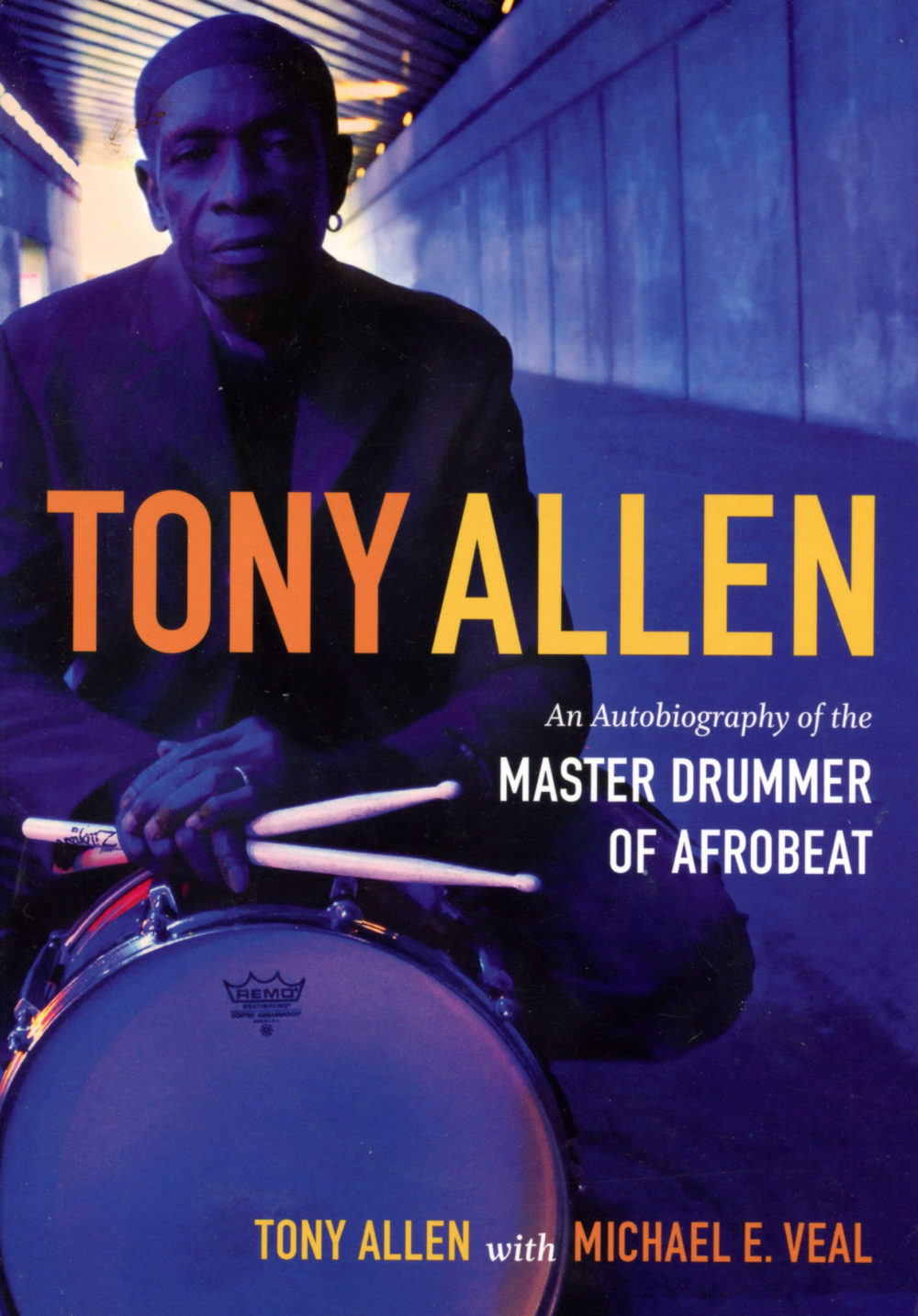

Michael Veal is a professor of ethnomusicology at Yale University, also a musician (bass and saxophone) and leader of the fine Afrobeat jazz band Michael Veal & Aqua Ife. He got to know Fela Kuti many years back, even sat in with the band Egypt 80, and wrote the book Fela: The Life and Times of an African Musical Icon (2000). Years later he came to know Fela’s most renowned former drummer, Tony Allen, and with Allen, he co-wrote Tony Allen, An Autobiography of the Master Drummer of Afrobeat (2013). Veal has worked with Afropop on programs about Fela and about dub music, so we go back. Afropop’s Banning Eyre visited Veal in his apartment in Inwood, New York, to talk about Allen’s life and music. This interview took place just as the New York City lockdown was starting to lift, and the conversation proved wide-ranging. This is an edited transcript with a focus on the central topic, the amazing Mr. Allen!

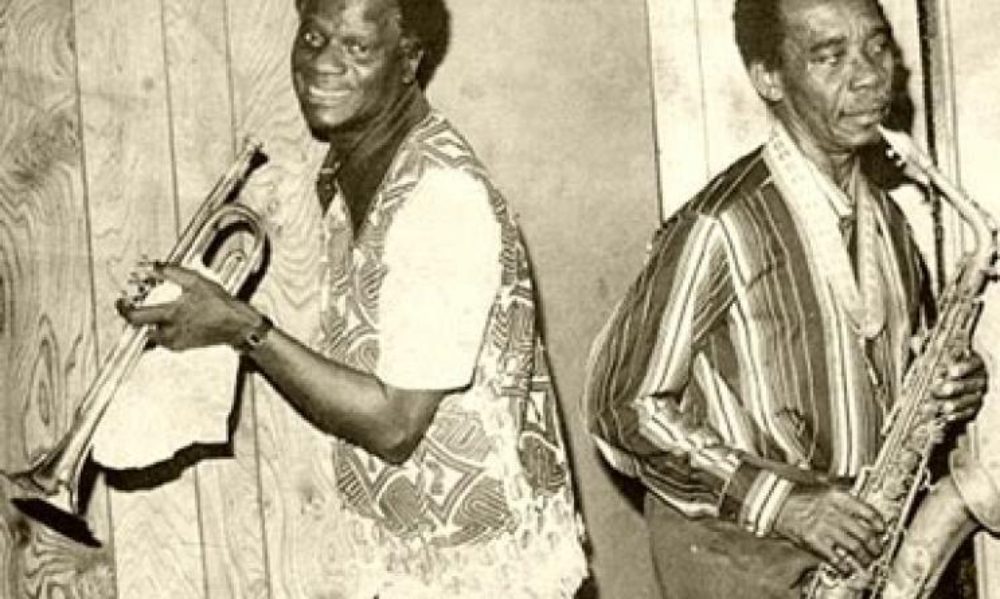

Banner photo of Michael Veal playing sax with Tony Allen on drums by Jean-Marc Laouena.

Banning Eyre: How did you get involved in Tony’s book project?

Michael Veal: Around 2000, Tony contacted me through a friend. He wanted to know if I was interested in co-writing his autobiography. And I said yes, because I think Tony Allen is one of the great drummers of our time. Tony was living in Paris, where he had lived since the mid-1980s. So from about the beginning of 2004, we started the project in earnest, but it took a long time because he was a touring musician. He was in and out of town a lot. And of course I had a job back home as a professor. So, I basically lived off and on in Paris for about five or six years, going over for two months here, three months there, two weeks year, six weeks there. That's when the bulk of the research was done, between ’04 and let's say ’08.

Let’s go back to his early life. What can you tell us.

Tony was born in 1940 in Lagos Nigeria, in what we refer to today is downtown Lagos, in other words on Lagos Island. Over the last few decades, Lagos has really extended outward to the mainland. But he was born in the heart of old Lagos. And he was born to a middle-class family. His grandfather I believe was a very well-known police constable. In fact one of the main thoroughfares in the area called Ikeja, which is one of the outlying areas of Lagos, is called Allen Avenue. And that was named after Tony's grandfather. So he came from a middle-class family. He had a bunch of siblings. And he just fell under the sway of music. At that time, it was highlife.

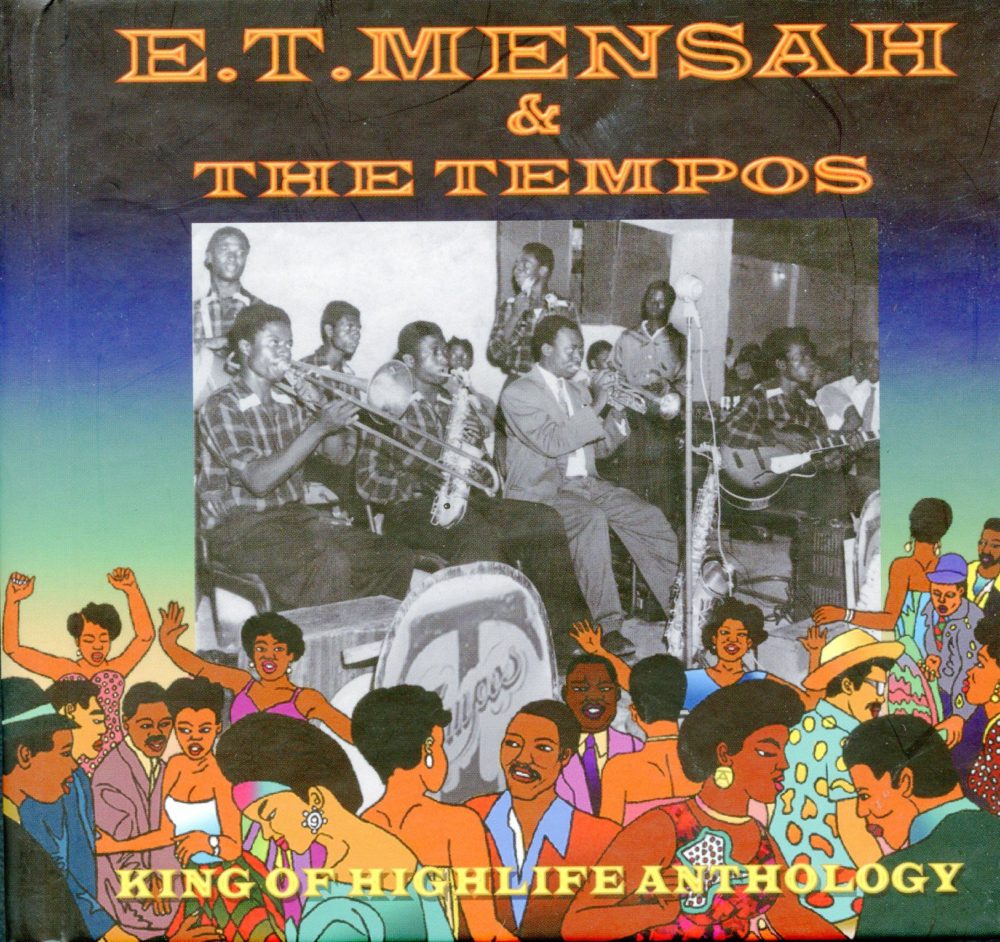

Highlife was the big popular dance music in Nigeria and Ghana at that time. Nigerian musicians like Victor Olaiya, and Eddie Okonta, Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson, and of course Bobby Benson. Bobby Benson had been trained in the band of E.T. Mensah, the Ghanaian king of highlife as he's known. And so there was a lot of dialogue and interchange between Lagos in Nigeria and Accra in Ghana. Those were kind of the two hubs of the highlife scene.

This is the ‘50s.

Yes, Tony started playing in the late ‘50s. Around the time he was 16 he started to play with Victor Olaiya, which is the same band that Fela Kuti got his start in. Fela was kind of a backup singer in Olaiya’s band, and Tony was the backup drummer. Actually he was in Olaiya’s second string band. That was his first gig.

One interesting thing in Tony's biography is that his heritage is part Nigerian and part Ghanaian. His mother was Ghanaian; she was a Ga and Ewe speaker. And Tony's father was a Yoruba speaker from Abeokuta in Nigeria. And so Tony grew up in this dual heritage environment in his home, culturally speaking. And of course the Yorubas, the Ewes and the Gas, those are three very prominent drumming cultures in West Africa. Lagos had a huge community of Ghanaian ex-pats living in Lagos at that time. And so Tony grew up in the midst of all this, and it really shaped him musically. And, he's speaking all three of those languages. In fact, Tony is known in Ghana by his Ghanaian name, Kwame.

He also grew up in the jazz age, with the great drummers like Gene Krupa and those types of people, the bebop era, with Max Roach and Kenny Clarke and all those drummers. Philly Joe Jones, Elvin Jones, and going into Tony Williams. So he's growing up in the middle of all that.

You write in the intro to the autobiography that Tony was alienated from traditional Yoruba culture.

Well, I think that Tony was basically a free thinker. That's the term we would use to describe him today. You know, many of the African cultures are very conformist. The social codes are very tightly regulated, especially cultures like the Yoruba, which is a hierarchical culture, very much concerned with decorum and presentation. You have got to dress this way for certain occasions and everyone's got to wear the same garments. They've got to be the same color. You've got to take the fabric to the tailor and have matching garments made for all the attendees of an affair. Could be a wedding, could be a funeral, could be any kind of ceremony. And I think Tony just for whatever reason… that just wasn't his vibe. He didn't buy into it, and that’s probably one of the reasons that he and Fela Kuti bonded later. They were both kind of freethinking, nonconformist people.

You know, a lot of the Yoruba music even today, the bulk of it I would say, is tied up with things like praise singing, in which you are going to extol the virtues of some prominent person in society. It could be a politician, a successful business person, a traditional ruler... All this rooted in the historical, traditional culture and Tony was just one of those people who rejected that, and that wasn't easy to do at that time.

Tony was in the independence generation, and those kids were expected to go on and become stewards of the nation once independence had been achieved. And Tony was from a suitably middle-class background. He could've gone into one of the professions, so to speak. But you know, like most musicians, once the music hit him, he had to do it, and that was his only option in life.

His parents, despite all that, were ultimately supportive of his career. He was lucky in that way. It's not the case in so many musical biographies in Africa. But he didn't initially want to be a musician, did he? He told his father he wanted to be an auto mechanic. But then there’s a moment when it switches, and he feels the pull.

Well, I think he always felt the pull, but he's a moderately minded person, and he understood the risks of a musical lifestyle. So after he got his first taste of the business with Olaiya, he didn't want to keep doing that. He went to engineering school and tried different things. But he didn't enjoy that either. He probably didn't enjoy the rigidity and the regulation of those types of professional environments. He liked the freedom and the creativity of the musical lifestyle, but the problem was just the instability of it. At that time, the bandleaders were pretty unethical people. They would get paid and drink all the money away, or gamble it away, or spend it all on prostitutes or some other form of frivolity, and wouldn't pay the band members.

He went through several cycles of that, and that's what drove him back to try more mainstream professions, until finally he decided, "I've just got to throw my hat in the ring into this musical thing, come hell or high water."

One thing I enjoy about his recollections is his detailed memory of all those negotiations. He explains exactly why he left each time. With Fela, he held on for a long time, but before that, he’s very willing to stand up and say if you can’t pay me, I'm going somewhere else. He had that ethic of feeling like, "Dammit, I should get paid."

Well, you know that's the music industry, not only in Nigeria, not only in Africa, but worldwide. Most of the people who are in it are in it to get high, get drunk, get laid or just to have fun and adventures. And that's why so many musicians and up getting ripped off, because they're not really concerned about their monetary interests. It's only the ones who are married or have kids, and who have people putting pressure on them to bring the bacon home. A lot of musicians are just in it for the good times. And Tony had a different perspective on it.

Of course, he liked to have a good time too.

He wanted to get paid for having a good time, because it was the good time that was making the music so great.

Let's talk about the evolution of his drumming style. You talked about how he was surrounded by traditions. But he never really played traditional music. So I'm wondering how that experience figured into the style he ultimately developed.

That’s hard to say. I know a lot of it was atmospheric, environmental. He was there in Lagos. Lagos is one of the great musical cities of the world. And you know, that was all the popular music he was hearing, and all the traditional music. The apala music, which was pretty new at that time. Sakara music and agidigbo music. Most these Yoruba street musics came from the interior, not to mention the musics played by the Ghanaian expats when they would have their parades in Lagos. So there was a lot of traditional music happening on the streets and all around and in the countryside.

Abeokuta, where Tony's father comes from, and also where Fela’s family comes from—that's a very rich city in terms of traditional Yoruba music. You have a lot of apala musicians and sakara musicians from Abeokuta. You also have the different musical styles associated with the different religious organizations, and the different Yoruba cults and so it's a very rich environment. He grew up surrounded by traditional music of various types.

And then of course going back and forth to Ghana. Ghana is also very rich and traditional musics, especially drumming. You have all the Akan cultures and so on. So this is just part of his background and part of his environment.

He talks particularly about being impressed with apala music. He cites Haruna Ishola. He says he heard that there was this rhythmic language inside it. So he didn't play these musics but he absorbed them deeply. Is that fair to say?

Absolutely.

Let’s talk a little bit about trap drums. They were relatively new in Africa at this time. Can you give us a timeline of when traps arrived in Nigeria? I mean if we’re talking the early 1960s, in Congo, they weren't even using trap drums yet. But it seems like one thing Tony did was to translate all the sounds in his ears onto the trap drums.

The drum set itself has diverse origins. It comes partly out of the military marching band tradition, and that it comes out of the circus tradition too. It was a novelty instrument in the circus. You have this percussion instrument with all these different drums and cymbals and all that, and it could be controlled by one human being. That was a new thing. And you know, as with most innovations, it was done to save money.

I can't tell you who brought the first drum set into Nigeria, but if I had to guess, I would guess that it was from the highlife bands. E.T. Mensah in Ghana toured Nigeria many times in the ‘40s and ‘50s and ‘60s, and that is generally considered to have laid the foundations for Nigerian highlife in the Yoruba area, in the southeast Igbo area, and also in the south-central area. E.T. Mensah had a very important drummer, Guy Warren, subsequently known as Kofi Ghanaba. Now Kofi Ghanaba had spent a lot of time in the U.S. playing jazz and learning jazz. He actually made a number of recordings while he was in the U.S. He was socially friendly with Duke Ellington and Max Roach and Charlie Parker and people like that. So he really brought that jazz concept of drumming into highlife. And if you listen to the old E.T. Mensah records from the ‘50s and ‘60s, you can really hear that the drums are back there doing something.

Typically in ensembles, you would have a battery of percussionists all playing different instruments: bells, drums, shakers, scrapers. It was a new thing that you could centralize all these parts under the control of an individual musician. And so the drum set begins to acquire its own identity in African music at that time. Tony, coming up in the highlife era, fell under the sway of great drummers like Guy Warren, as well as the local Nigerian drummers. It's a long list of people.

Dance band highlife bands with horn sections and all that were really kind of an African adaptation of the American jazz big-band concept. Tony was also hearing all those jazz drummers from the big band era: Papa Joe Jones and Gene Krupa and Sonny Greer and all of those people. And then as the ‘40s turned into the ‘50s and swing gave way to bebop, he came under the sway of all those great bebop drummers. Now the whole significance of bebop is that that was the music of the virtuosi.

So now you've got virtuoso drummers emerging. They are not just keeping the beat anymore, but they’ve got a lot of chops and they’re playing all this technical stuff and creative, imaginative, interactive stuff. Max Roach and Kenny Clarke and Philly Joe Jones and Art Blakey. And all the drummers of that generation, and then the ones that came to prominence after them in the ‘60s, like Elvin Jones and Tony Williams. So Tony was hearing all that. And of course, they were also importing those Blue Note records into Nigeria. And there was a time period in his adolescence when Tony was working as a deejay, and people wanted to hear highlife, and wanted to hear jazz.

So Tony was spinning all those Blue Note jazz records at parties when he was deejaying, going back and forth between highlife records and jazz records. In fact, the jazz records would come in the chillout portion of the set. Play the dance music. Then people want to relax, you put on some chillout records: Blue Note.

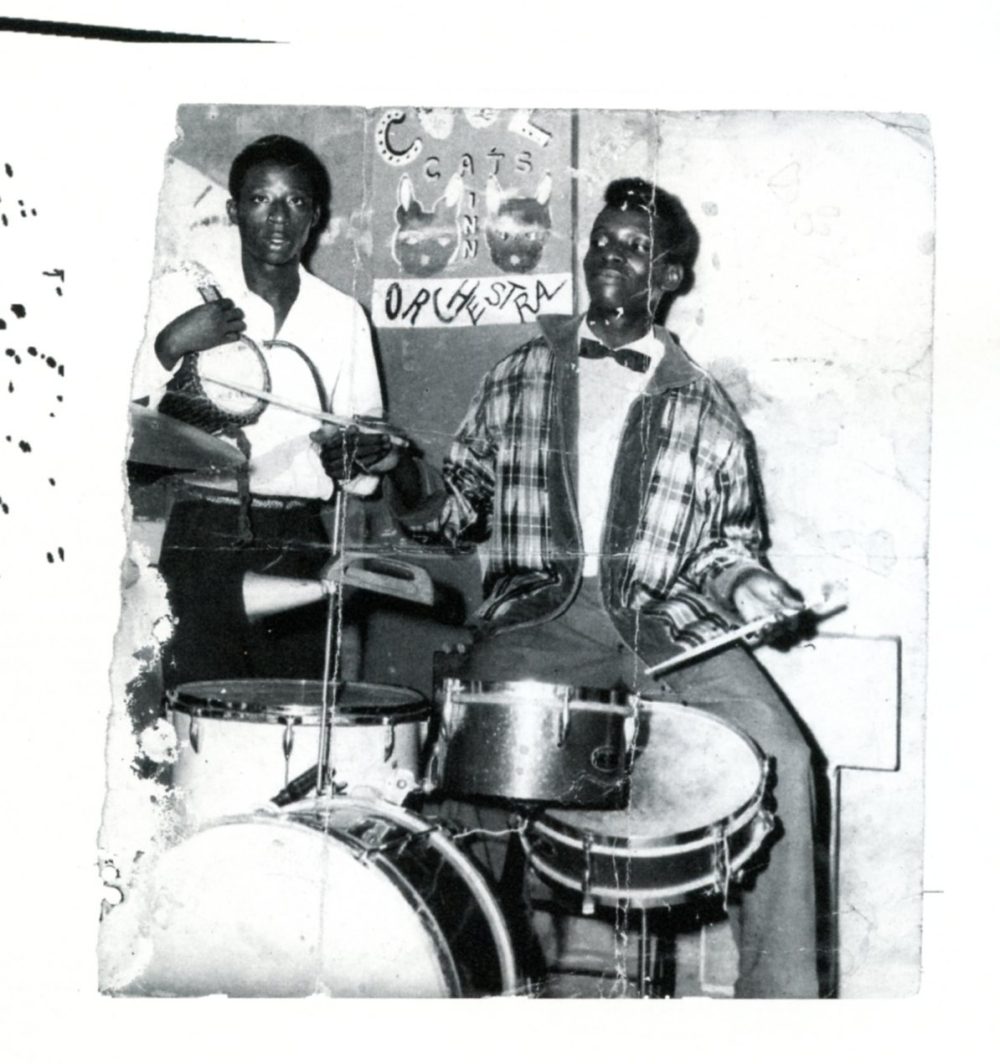

When he starts playing with the Cool Cats, he's playing what he calls “clefs,” or clavé sticks. But there's a moment when the drummer is gone, and he is recruited to the drum kit. And the way describes it, he is a little bit unsure first.

But his learning curve was remarkably rapid. When the other drummer leaves, they said instead of finding a new drummer, just let Tony stay on the drums full time. And from that point on, his drumming develops rapidly, which means he had a very strong love and passion for it, and also a strong ability. There are times in the early years when people do things like paying him more than they pay the other members, or making special accommodations, because they recognize his outstanding talent from an early age.

In 1964, Tony meets Fela. It's a crucial moment. Tell us about it.

The reason that Fela and Tony originally met is that they were both jazz heads. Fela had come back from London. He got his degree at Trinity School of Music in London, and he wanted to be a jazz musician. He was playing the trumpet at the time. Most of the highlife band leaders were trumpeters. And Fela also loved Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie and Miles—early Miles, and Clifford Brown—those types of musicians. So he wanted to play jazz when he first got back to Nigeria and he needed a drummer. He couldn't find a drummer. And people told him, "Oh, you’ve got to hear this guy Tony Allen."

So they are basically shooting for the same thing. And that's when Fela started his quartet, the Fela Ransome Kuti Quartet, which is documented. There are about two singles they put out, playing stuff that sounds kind of like Kind of Blue, a little bit like Miles or Kenny Dorham or somebody like that. But he couldn't make any money from it. So it was more of a style thing than something that was vibing with the environment that they were in. So Fela remade the band as a highlife band called Koola Lobitos. That's when things started to take off.

Why the name Koola Lobitos?

Lobitos means "little wolves” in Spanish. It's interesting that in Nigeria they would choose a Spanish title. That just tells you how pervasive the influence of Cuban music was. By the mid-century, Cuban music had turned the world upside down. We understand this better in Francophone Africa because in the Congo and in Mali and Guinea and Senegal, there wouldn't be any popular music as we understand it without that formative influence of the Cuban montuno-based music—Beny More and Arsenio Rodriguez and Chappottín. Then going into the mambo era with Tito Puente and Machito, and then going on to the ‘60s and ‘70s into the salsa era with all the brilliant Cuban-based music coming out of Puerto Rican New York. Like Hector Lavoe and the Fania Allstars and Johnny Pacheco and Ismael Rivera.

That turned Africa upside down, and it even influenced the Anglophone areas, even though those areas were much more drawn to the Anglophone parts of the diaspora, primarily African-American music like jazz, but also Trinidadian calypso. But it was all in the mix. So that name Koola Lobitos reflects the influence of Cuban music across sub-Saharan Africa.

It's so interesting that the models are different in Anglophone and Francophone Africa. So the name reflects a lot of influence, you do hear it in the music to a degree. I mean all highlife has a clavé-like timeline to it.

Yes. OK, so now you've stepped into volatile territory. The whole concept of the clavé, which we understand in the United States in the most simplistic format. [Claps: 1 2 3 12]. But Africans would just call that a timeline pattern. And there are innumerable timeline patterns across sub-Saharan Africa, but the clavé concept has been emphasized in the United States because of its closeness to Cuba, and Cuba is the laboratory of Africanist concepts for the U.S.. It's like the shorthand version of that whole huge continent that is so musically and culturally diverse that most Americans are unable to deal with it. Very few Americans want to deal with the cultural complexity of Africa, African-Americans included. So Cuba is very interesting, because it's a very potent laboratory for the formation of Africanist musical concepts, of which the clavé is probably the most recognizable.

Last year, I was in Ghana speaking with John Collins about clavé, and he has a theory that musicians in the Caribbean developed it as a way of inserting 6/8 time into 4/4 time, which was favored by the colonizers. The implication was that triple-meter rhythms were often associated with non-Christian religious practices in Africa. [NOTE: This comment led to a fascinating conversation about timelines, but for another occasion…]

Fela himself composed a handful of songs in triple meters, but almost all of his songs were in some variant of 4/4. So coming out a Christian religious background, growing up playing church music, you know, Fela was a classic what they call "son of a preacher man." You know, strict religious parents, so he goes crazy as a reaction against all of that. But you hear the church influence in his music. The organ. You know they're playing that [Sings an Afrobeat groove] and then those long organ tones. That's what confers that air of righteousness, and the sense of the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

Let’s get back to Koola Lobitos.

Koola Lobitos became like a workshop. And Fela was very fortunate because he had all these musicians on hand just to execute a new composition when it came to his mind. You know, there was a lot of turnover in that band because Fela himself wasn't very different from the other Nigerian bandleaders. He wasn't treating musicians very well. He wasn't paying them well. So there was a huge amount of turnover in that band, as in all of Fela’s bands over the years. But they got a lot of work done. If you listen to that Koola Lobitos music, you hear of fusion of all that highlife of E.T. Mensah, and Victor Olaiya, and Roy Chicago and Cardinal Rex Jim Lawson, a fusion of that with the growing influence of r&b. You hear those dominant seventh chords that you find in the music of musicians like James Brown and Otis Redding, Stax-Volt, Aretha Franklin. And you hear the Cuban influence too. And there was also a New York boogaloo influence. It's all in there. And that's the type of highlife fusion they were playing until 1969.

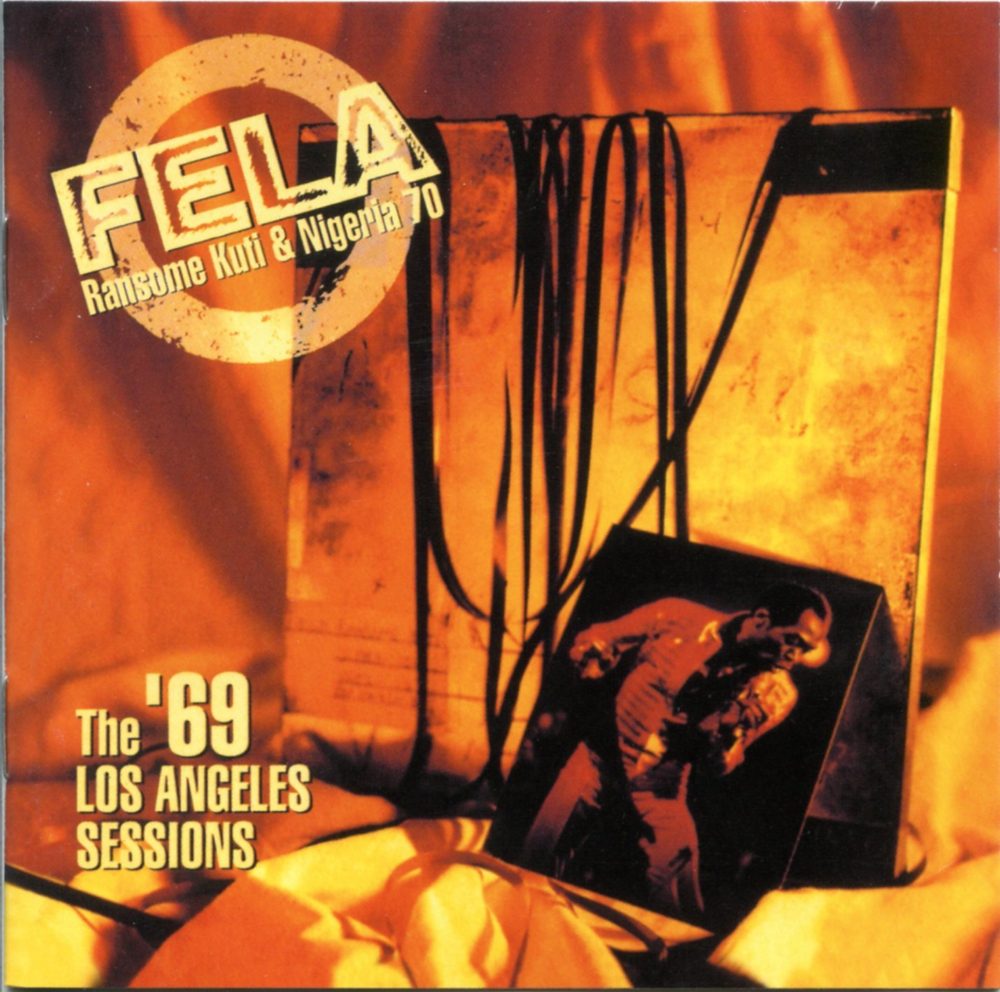

You write that it was in the recordings that Fela made in Los Angeles that year that Tony's Afrobeat drumming style really comes together.

They were only supposed to tour the U.S. for a month or two, but they got stranded in L.A.. There were immigration problems. The civil war was going on back in Nigeria. So they ended up staying in L.A. for nine months or so, and that transformed Fela in terms of him becoming a political artist and reconceiving his music as a medium for politics. It also helped to transform Tony's drumming. Because Tony had a friend in L.A. named Frank Butler. Frank was a well-known jazz drummer in L.A. He played with Miles on the original recording of Seven Steps to Heaven. And he played with Coltrane on the album Kulu Sé Mama (1967).

So Frank Butler was a very respected jazz drummer, and he befriended Tony. They used to practice together, and he showed Tony a lot of tricks, how to loosen up his wrists, and how to develop his independent coordination and how to develop his dexterity. And so basically, L.A. is when Tony Allen’s drumming style takes off like a rocket. Now he was already recognized as a great drummer before L.A.. But once he got that last infusion, he just went beyond.

And that's what we hear in those Africa 70 recordings.

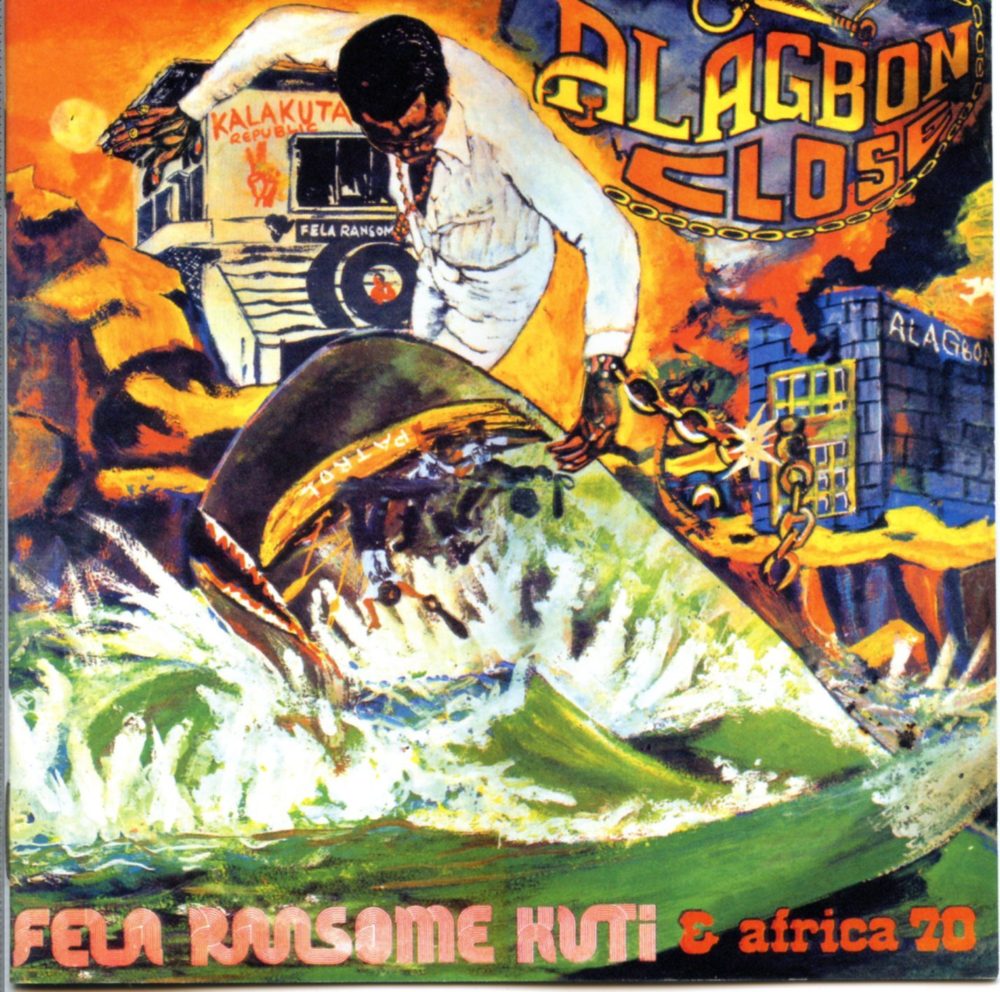

Absolutely. You listen to stuff like “Roforofo Fight.”

My favorite!

Or “Question Jam Answer” or “Confusion” or “Alagbon Close” or “Noise for Vendor Mouth,” or “Kalakuta Show.” Tony has just exploded into greatness. He and Fela were linked at the brain, despite whatever else might be going on with the business. They were totally in sync with each other. That is some of the greatest drumming in my opinion that's been recorded since World War II. It's jazzy. It's funky. It swings. It's got the overtones of traditional African music, of various sources in there. It sounds totally hip and slick, but at the same time, rootsy, and even a little bit traditional. So that was when Tony just achieved his glory.

You drew my attention to a track I hadn't really pay attention to before “Fefe Naa Efe.” You cite it as a particularly great example of that glory.

Absolutely. The way he's playing the hi-hat cymbals is loose like a jazz drummer, and the bombs and the accents are like a jazz drummer. But it's also funky like one of James Brown's drummers. It sounds like something Clyde Stubblefield would play. And the line that Fela wrote on top of it, and the way Tony interacts with the horn line. It's got that swing, very loose and jazzy.

Now later in Africa ’70, the music tightened up. Basically, as Fela became more in conflict with the authorities, the music started to tense up. It reflected all of that. So then you get stuff like “Alagbon Close” with those tense rhythms, or "Confusion,” also very tense, but back in the early ‘70s with Africa ’70, it had that loose, fun, funky, jazzy feeling. And that's the highlife influence. Like the song “Water No Get Enemy.” That's really the same way those drummers used to play in the highlife bands.

The key to understanding that is the drummer is just a partner in the percussion section. He’s not necessarily the leader. You've got the rhythm congas, you’ve got the lead congas that are playing interjections. You’ve got the shekere, the sticks or clavés. They are all playing this matrix of parts, and the drummer is just kind of riding on top of it, pushing the music when it's time to push it, pulling it back when it's time to restrain it. Simmering. Push it again! Break it back down! Simmer. So that whole dynamic. Tony was a master of that. And the reason his music shines so much with Africa ’70, is that he's got this bed of percussion that he can just ride on top of and interact with and interject.

So when does Tony start doing solo work on the side?

His first solo record was 1975, I believe. I think that was Jealousy. And that is a rhythm that he reworked several times over the years. And that is also highlife influenced, very jaunty and bouncy. He did three records with Africa ’70 on which Fela performed, but they were released under Tony's name. One was called Progress. One was called No Accommodation for Lagos, and one was called Jealousy. And those are great records. They are very much in the Africa ’70 mold, but they do include drum solos. The Africa ’70 tracks that also include drum solos include "Open and Close," which is another great track where you can what Tony's drum soloing language was like. That solo on “Open and Close” is very much influenced by Max Roach. In fact it compares very closely with the solo that Max Roach plays on Sonny Rollins’s "St. Thomas."

So then we get to 1978 when, after 15 years, Fela and Tony part ways. Tony says Fela was a "slave driver" using his money for his political aspirations rather than to support the band, and that was the final straw. But I get the impression in the book that they stayed friends, and Tony said as much in my interview with him in 2007. He said he quit the band in order to preserve the friendship.

Well, you know how it is when you're young you're a kid, you have a best friend. You do everything with your best friend. You guys are inseparable. And then something bad happens. Maybe he takes your girlfriend, or you take his girlfriend, something that just puts an irreparable split between you guys. So now you kind of hate the guy, but at the same time you've got all this background of the stuff you get together, fun you did together, and adventures you had together, and all this amazing music you made together. So you can't really destroy that bond. It's just that the bond has become more complicated. So they kind of intertwine in and out of each other's lives for the next 20 years, until Fela passes away in 1997.

Why did Tony chose to live in Paris?

Tony started out in London, but he moved to Paris because that was one of the centers of the globalizing of African music at that time. The French producer Martin Meissonnier was responsible for bringing Sunny Ade to the wider world. He also produced records with Manu Dibango. Martin was French and after he finished working with Island Records on the Sunny Ade project in London, he moved back to France. Paris had many, many, many African musicians who had moved there as ex-pats, because this is now the beginning of the era of globalization, which is just a code word for neo-colonization. The African economies were declining. That means the African music industries were declining. So you get all these African musicians moving to Paris, and beginning to aim their work equally at global audiences as they had aimed it previously at local audiences.

Someone like Youssou N’Dour, for example, began to bifurcate his releases from that time. He would release one set of recordings for the global audience, and another set of recordings for the local audience in Senegal.

Papa Wemba did the same thing from Congo.

Martin Meissonnier had previously worked with Fela before he worked with Sunny Ade, and that's how he and Tony linked up. And also, Tony had done some independent work with Martin. He played on one of Sunny Ade’s albums, Aura, and he worked on a couple of other Martin's projects. So they had a cordial relationship, and a business relationship and when Martin moved back to Paris, he kind of opened the door for Tony to come, because he knew that Tony was struggling, trying to make a name for himself. And so Tony moved to Paris and began his second career, and basically his second life.

Which has so many dimensions, which we’ll get to. But it’s odd that Tony never really learned to speak French. When I asked how his French was, he said, “Not good.”

Well, he has three sons in France who didn't speak English.

Yes that's what he said: he only spoke French with his kids. But he seemed very happy being in Paris when we met in 2007. He seemed to have real freedom to pursue all these different musical directions.

Well, it wasn't all freedom. He went through a few years of struggling heavily in France because of albums like Aura by Sunny Ade, or even his own Afrobeat Express. The vogue at that time was drum machines. This was the period of the mechanization of popular music, and that affected African music too. So Tony would record these great tracks, and the producers would either wipe the tracks, or use them to trigger some electronic drums, and for someone who was a great drummer, it was a very demoralizing time for him. In fact it was a very demoralizing time for drummers around the world. So he was just experiencing a variation of that in France. And that went on for several years until finally, it broke, I guess in the mid-to-late ‘90s.

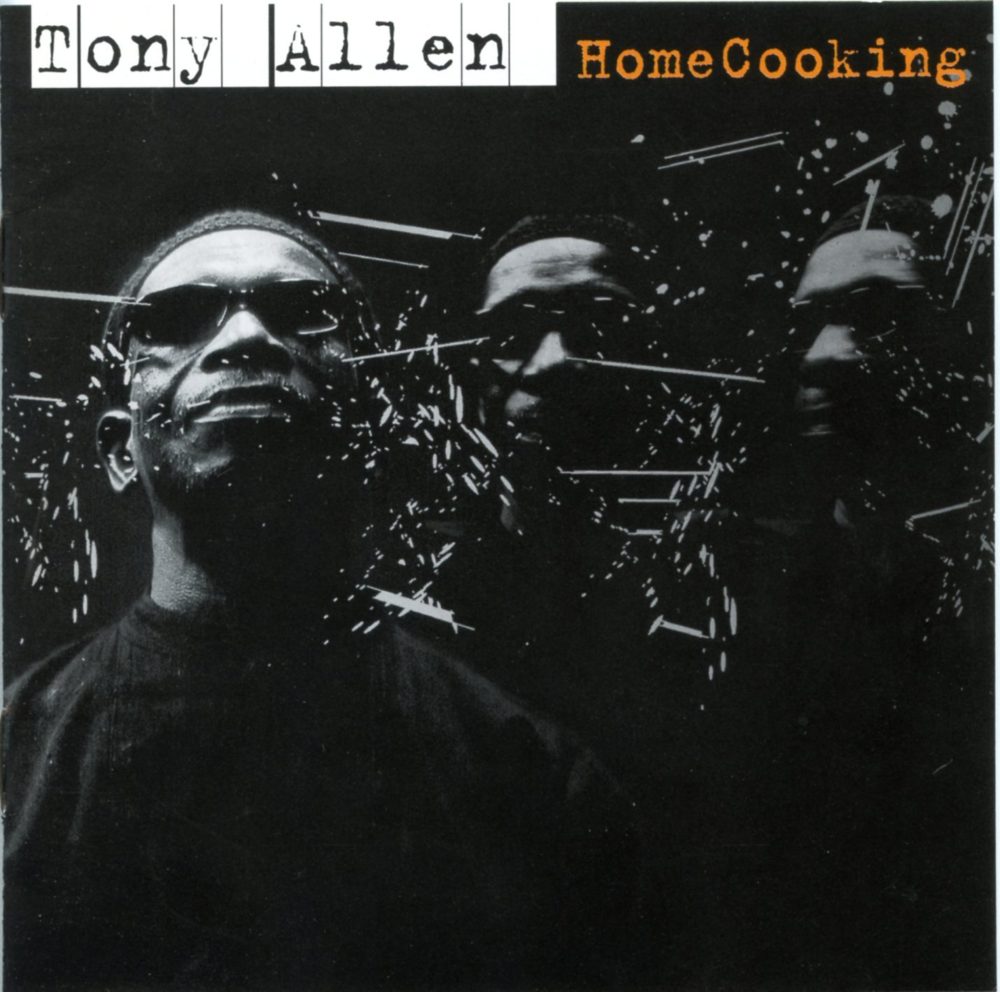

Then finally his second career begins to pick up with recordings like Home Cooking, and Black Voices. Those are two early recordings that he made with members of Parliament- Funkadelic like Gary Mudbone Cooper and Michael Clip Payne. I believe the genius keyboardist Bernie Worrell might turn up on a few of those recordings. So these were all Tony sort of using his Afrobeat drumming style as a kind of canvas on top of which there would be all this atmospheric, dub production, techniques that were popular at that time, and so-called electronica in the 1990s. That began a reinvestigation of dub production techniques, but this time around, Tony was able to integrate it in a way that was more consistent with his own aesthetic and tastes.

So we’re talking about these albums, Home Cooking, and Black Voices and there was one called Psycho on Da Bus that he did with an electronica artist named Dr. L, Liam Farrell. And there was another one called The Allenko Brotherhood Ensemble. Oftentimes the vocals were done by Tony himself. His singing was more fragmentary, kind of asides and quips. It wasn't like he was really singing on the microphone. But he could get a quintet, sextet, septet together, depending on the occasion.

By the time I met him, he was touring incessantly, all over Europe, touring the United States pretty regularly. Touring Asia. He played on Reunion Island. He played in Japan. He played in Israel. He played I believe in Istanbul. So he was working an incredible amount, and this was when he was approaching his 70s, or was in his 70s. So the last part of his career was incredibly active. I don't know how he kept up the pace. And then there was the collaboration with Damon Albarn, who was kind of a mainstream British pop star. That was a new world of collaboration for him, not only with Damon, but other pop stars at that time. So it was really a glorious period for Tony. I think he had a ball. He was getting the acknowledgment and recognition he rightfully deserved, and he made some great music during that era.

I take your point about electronic drums. It really wasn’t the best time for a virtuoso drummer to land in Paris, was it?

It was also not the best time for an African to arrive in Paris because this is when the whole backlash against immigration begins. François Mitterrand was an immigration-friendly president. But everyone who came after him was pretty hostile, Jacques Chirac, Nikolas Sarkozy, on down the line, and it's still very hostile today for immigrants, especially African immigrants. So was a very difficult to try to put roots down in Paris as an African, and as an African musician. But he kind of stayed with it. He didn't give up. He fought the good fight and in the end his career was a triumph.

Tell me about his wife.

I think he got married around 1987 and had three sons in quick succession. He's now a grandfather, because all those guys have now had kids. And he is a great-grandfather with his Nigerian family, so there was a tribe of grandkids and great-grandkids around him. Toward the end of his life.

Sylvie Nicolet was his wife. I don't know much about her background. She grew up in the 17th arrondissement, which is like the ritzy money area of Paris. Her father was a well-known surgeon. These are white French people. She got married to Tony fairly young.

But the interesting thing about Tony's life in Paris is that although he moves there at a very inopportune time, he was able to enjoy a level of stability and comfort that very, very few African musicians are able to enjoy in Paris. He basically had a stable middle-class life. He was the primary breadwinner in his family. And he was making his money exclusively through his musical endeavors, and so in that sense also, in the personal sense, his life was a triumph.

There are some great collaborations with African and Caribbean musicians in his later years, Ray Lema, Ernest Ranglin, Angelique Kidjo, and Oumou Sangare, even Afel Bocoum on his upcoming album, Lindé.

Another interesting element of Tony's second career was all of his collaborations with electronic artists. Such as Dr. L, whose real name is Liam Farrell. And Moritz von Oswald, who is the Berlin minimal techno artist, who is most usually associated with Basic Channel, the techno label. And also the Rhythm and Sound collective which is a kind of neo-Jamaican dub project that Oswald and Mark Ernestus does with Caribbean musicians. Von Oswald and Ernestus were the brains behind Rhythm and Sound. Tony also collaborated with Detroit techno artist Jeff Mills. So there are very interesting examples of him fitting his Afrobeat style in the context of electronica, and doing it in a way that was much more organic, and more successful than what the heavy-handed producers are doing in the ‘80s, who just wanted the stiff drum machines to be on top of it.

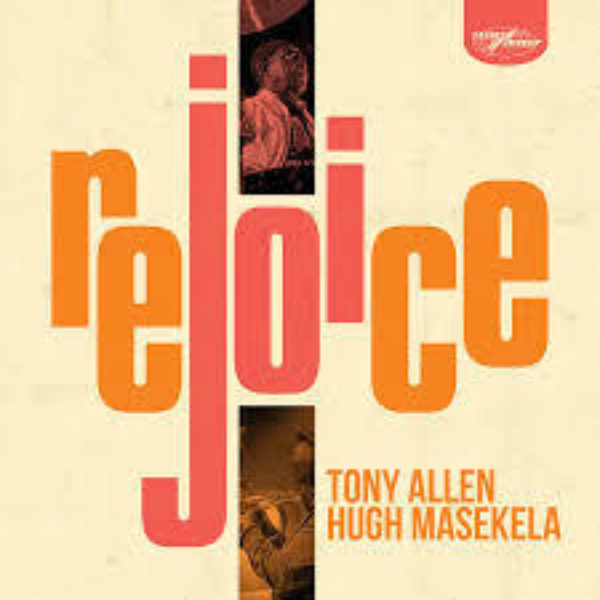

I saw him with Jeff at the Apollo in 2018. It was nice, a very open, spacious sound. I also love the jazz albums he did, the Art Blakey tribute and The Source. And I love the album he did with Hugh Masekela, Rejoice. It was only released recently, but recorded in 2010. That album has a really sweet vibe about it. It's interesting that after this whole journey, he comes around to playing in this truly jazz context once again.

Well, that's how it is toward the end of people's lives, they often come full circle. And so this goes back to the days when he and Fela were trying to play jazz on Lagos Island, playing for little parties and social events, playing small band jazz, in the style of Miles’s Kind of Blue, or Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver, or Lee Morgan. The Art Blakey tribute album is actually a beautiful album, and it's nice the way they packaged it. They designed it like one of the classic Blue Note albums that were designed by Reed Miles, with photos by Alfred Lion. So it was very beautiful to see him come full circle like that, and it also kind of brought out the jazzy overtones of his playing, in a way that we hadn't heard since the years with Fela.

Fela’s Afrobeat is heavily influenced by jazz. It's full of solos, and the way that Fela composes the horn charts, it's like African big-band music. That's really what Afrobeat is. It's got the James Brown influence. But it's got the John Coltrane influence in the harmonies; it's really very jazzy.

So at the end of his life, Tony was playing in venues like Carnegie Hall, Royal Albert Hall. He was really enjoying the triumph of his career in the early 2000s and into the teens.

And he did albums like Secret Agent, Film of Life and Lagos No Shaking. On that last one he was trying to go back into the traditional Afrobeat angle.

And he did an album with the Chicago Afrobeat Project. When I spoke to him the last time, after that Jeff Mills concert, he seemed so comfortable moving from one thing to another. He said that if he didn't do that, he would get bored.

Tony was always a levelheaded guy. He liked to have fun, to have a good time engaging in his own hijinks. But he always kept his head on straight. He was always focused, and he always took care of business. And that kind of blew all of his challenges and roadblocks away.

Thanks so much, Michael. You’ve really given us a deep picture of an iconic artist.

Related Audio Programs