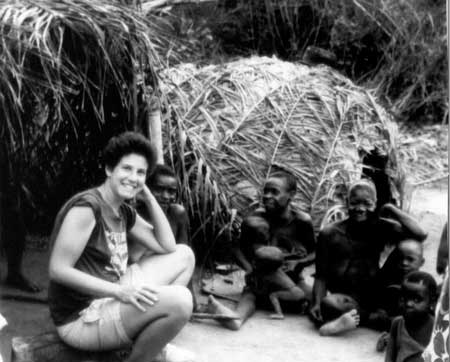

Michelle Kisliuk is an ethnomusicologist at the University of Virginia. In the mid-80s she made her first excursion to the Central African Republic to study the music and dance of the BaAka pygmies. She was interested in BaAka culture and society, but beyond that, she wanted to be a participant, to learn the music and dance, and to return able to teach it to others. Through subsequent trips, she did all that and more. Her book “Seize the Dance! BaAka Musical Life and the Ethnography of Performance” (Oxford University Press. 1998) is exceptional not only as a description of BaAka life and music, but also as a narrative of crossing cultural borders. Michelle was ushered into the world of the BaAka by Justin Mongosso, of the neighboring Bagandou people. Michelle and Justin later married, and both were contributors to Afropop’s Hip Deep program “Seize the Dance! The BaAka of Central Africa.” Banning Eyre interviewed them, and here’s the transcript of their conversation.

B.E.: Welcome Michelle and Justin. To begin, introduce yourselves and tell us how you came to work with the BaAka.

M.K.: My name is Michelle Kisliuk. I'm currently an associate professor of music at the University of Virginia, where I teach ethnomusicology and performance studies.

J.M.: I am Justin Mongosso, Serge, from the Central African Republic. Activist for the pygmy groups in the Central African Republic and Congo Brazzaville.

B.E.: Michelle, why don’t you briefly, decode the terminology for us. “Pygmies,” “forest people,” “BaAka.” How should we use these terms?

M.K.: The people that I learned from call themselves BaAka—and I focus in the Central African Republic, which we often refer to as Centrafrique, a one-word French version that is less cumbersome than Central African Republic. The forest people in the Central African Republic refer to themselves as BaAka [bee-AH-kah]. The root word is Aka, the plural is BaAka. Ba is a plural prefix. Some people say Bayaka [bai-AH-kah] around the area of Bayanga where Louis Sarno has spent a lot of time. In the area that Justin comes from and where I worked, they say BaAka but their neighbors call them BaMbinga, and in English or French, they are referred to as pygmies or pygmées. Unfortunately, both terms—pygmy and BaMbinga—have been used pejoratively. So it's a bit tricky how to use these terms in a way that doesn't reference pejorative uses. I often tell people who ask me that when I do decide to use the word “pygmy" I explain that that is the only word in English that refers in general to many groups of people who live across the equatorial rainforest and speak different languages and refer to themselves by different names. But because these people have been exploited and seen as backward, these terms have often become pejorative.

One anecdote that I tell is that in Cameroon, the government once had a campaign of saying that you cannot refer to the forest people as pygmies, but you have to refer to them as citoyens, citizens. One time I used the term citizen or citoyen just in passing with someone (a non-pygmy who had spent time in Cameroon) and they felt that by using the term citizen, I was insulting them by calling them a pygmy. So it gets very complicated. I prefer just to refer to them as they refer to themselves, BaAka, or Bayaka, forest people, and when it is clear how the term is being used, then I can say pygmies.

B.E.: I want to emphasize that the BaAka are one of many groups that get referred to as pygmies. Isn't that right? What is the commonality that makes for that larger group we call pygmies?

M.K.: What brings all the equatorial, so-called forest people together—the people who are called pygmies—is actually a huge topic for debate among anthropologists and linguists and others. The most common understanding is that all of these people at one time were one large group of people who spoke the same language, but over time, and with the Bantu expansion, they separated into different groups, and developed different languages or lost their own language and adopted the language of the neighboring Bantus. There's even a theory that links the equatorial forest people (pygmies) to the San, Khoisan, the bushmen of the Kalahari, and says that they were at one time all one group. [See Grauer, for more on this.]

B.E.: While we’re speaking about origins, I remember in Mali, at the Bandiagara caves, we were told about a very small people who once lived in tiny dwellings in the caves. They were called the Telem, and guides told us that they were the original pygmies, that they left this area and went south and became the pygmies. Have you ever heard that?

M.K.: Yes, I have heard that. I have heard people from Togo say, when they saw pictures of pygmies from Central Africa, that those people were their ancestors. In western Ghana, this is also part of a traditional belief system where little people with invisible arrows can harm or do good mystically to someone. This is also reminiscent of the idea of the pygmies. So I think the idea is widespread across parts of Africa where pygmies no longer are, that at one time this was the population who lived there.

B.E.: And I imagine that this is probably also a subject of considerable anthropological and scholarly debate.

M.K.: Yes, yes, it is. I wouldn't say there are that many people involved in the debate, but the people who are are very adamant about their ideas.

B.E.: So, it is fair to say that the oldest origins of the forest people are not entirely clear to us.

M.K.: That is true. It is not completely understood. The more recent genetic research, the human genome project, has shed a lot of light on that, so things are becoming clear that could not before the genome.

B.E.: Fascinating. And of course, when you have mysterious origins, other mysteries arise. That brings us to the idea of his “utopian narrative” that you write surrounds the pygmies. Give us a sense of that.

M.K.: Yes. This utopian narrative takes a number of different forms, but I found that it has a consistent sense of binary opposites. So, either forest people need to be seen by others as sort of living in an Eden, and living an Edenic kind of life, or as fallen dwellers in Eden, that they are somehow tarnished, and not living in the pure way that they ideally should be. And in that case, they are vulnerable to the ideas of missionaries and other people who would like to change them. So they end up being caught in the middle of other people's utopian or fallen utopian ideas.

B.E.: Give us a little sense of the content of these utopian narratives. And maybe as part of that, you can describe the general environment in which you did this work: Forest, rivers, remoteness-- give us a picture.

M.K.: Okay. Well, they live in the oldest and largest uninterrupted expanse of the so-called virgin rainforest in the world at this point. A lot of incursions by lumber companies and village farmers have taken place in this area, but it is still the largest. They live in small, cooperative, extended family groups, and they get together in larger groups at different times of the year, and then they will separate into their smaller family groups for certain seasons, such as honey season, and caterpillar season. One of the books that linked a utopian idea of the forest people with an idea of their music was the famous book by Colin Turnbull published in 1960. Turnbull was an anthropologist who became very well known because his writing was very accessible and personal. He was also an irritant to a lot of professional anthropologists because of how accessible his writing and how personal his writing was. The book was called The Forest People, and the subtitle was "A study of the pygmies of the Congo." In the reissue of the book, they have taken out that subtitle, perhaps because of the pejorative associations with the word pygmies. But it is still in print. It is dated at this point. It uses language that would no longer be used in a current monograph. But it is still so well written and so sensitive to the people that it is still assigned as a college text.

He had an extreme sensitivity to the music. Now, his work was focused in the current Democratic Republic of Congo, near Kissangani. So it is very far from the area where I worked, or where Justin comes from. But it established an idea of African forest people and their relationship to the music that was imitated by many, many adventurers after him, and that is echoed in the work of Louis Sarno, and I would say it is echoed in my work as well. I try to echo it consciously. I also met Colin Turnbull as a graduate student, and that was one of the things that spurred me to go ahead to try to travel to central Africa and learn about the music. Because in fact, he could not teach me how to sing any of this music that he was so fond of. And I had studied other forms of African music from West Africa that I had been able to learn, and someone had been able to teach me. And I had learned something very important by being able to perform some of it, that I was committed to try and see if this was something that I could learn and try to teach to other people.

B.E.: You write about that moment in the classroom, when you asked Colin Turnbull to teach you a song, and he couldn't. It seems like that moment was very important in cementing this idea of a performance-oriented career in research. That seemed like an anomaly to you right off the bat, didn't it?

M.K.: Yes. Especially since he was interested in performance and theater, and he was a very musical person. So I didn't quite understand it except that he hadn't been trained in the way I had to learn African music in a way that you could then teach it and join in directly.

B.E.: Lay out the general historical context for this part of Africa. In broad terms, how have colonialism and the European and Arab slave trade affected the region, and the forest people in particular.

M.K.: This area of forest extends from eastern Cameroon, southeastern Cameroon, into the southwestern Central African Republic, the northern Congo, and it actually also extends across the Ubangi River into the Democratic Republic of Congo. But this big swath of rain forest, the core of it is what is now the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve in CAR (which is administered in part by the World Wildlife Fund) where there is more of a concentration of wild elephants than anywhere else in the world. BaAka are very mobile, and they have ways of being where they want to be and disappearing from places where they don't want to be. It's a survival strategy, and during the colonial period, what I read and what I heard was that they would go further into the forest, and the villagers who wanted to avoid the brutality of the colonial concessionary companies and others, and colonial administration, would join them in these forest camps, or live next to them in these forest camps. That way they were able to keep some distance from the forced labor, the collecting of rubber and other kinds of forest labor. When we were there, we would sometimes see these metal cups that they were using, and I asked about those, and Justin told me that these were left over from colonial times. Is that correct, Justin?

J.M.: Yes.

B.E.: In terms of the slave trade specifically, is it fair to say that very few forest people were ever captured into slavery and taken to foreign countries?

M.K.: I think it would be fair to say that none were. Well, I can't know that for sure, but I would be surprised if any were captured into slavery. I don't believe that any of the forest people were captured and sold into slavery. I think they would have been very hard to access. I have never heard of any connection between the slave trade and actual forest people being captured and sold into slavery.

B.E.: So when Robert Farris Thompson talks about the music of the pygmies "leavening the blues" he's being a little bit more poetic than precisely historical?

M.K.: Yes. I would say that when Robert Farris Thompson said that the yodel of the pygmies "leavened the blues," he was being poetic. But there is another aspect to that because BaAka neighbors, such as the BaNgando (Fr. Bagandou) people—Justin is half Bagandou—generations back, had a culture relatively parallel to BaAka. They yodelled. They did net hunting. So, if people like Bagandou people or their neighbors were captured, they could have also come directly with a kind of forest yodel, which according to BaAka, isn't as good as their own, but is reminiscent and is sometimes quite virtuosic. Even now, some of those people continue the older traditions.

B.E.: Interesting, and perhaps quite up to the task of leavening the blues as Thompson had it. Maybe this is a good time for Justin to talk about the dynamic of the BaAka and the neighboring people. Tell us about the history of that relationship, and just generally how it worked, the interaction there. It's quite fascinating and kind of unfamiliar to a lot of people.

Justin Mongosso: Okay. I grew up in a Bagandu Village. That is in the equatorial forest. And when I was young, about five or six years, I got to know pygmies, and it was a privilege for me to get to know them because it was a big barrier between my people and them. When I started to become a young boy, five or six years, I was interested in them. I got to know them and I learned their language. But still, I think I was lucky enough to know them because most people my age did not have the opportunity to make this connection because my people, for generations, they saw pygmies as not like living beings. I think my case was a little bit different, because my parents were very nice to them, so they allowed me to know them. But since I was growing, I developed to know them more, and I started to speak the language.

So I will even say that I learned Diaka [the BaAka language] before I went to French school. That's why I developed the ability to know them. But something was striking me, because I didn't know why my people were treating them in a way that was not pleasing. But as I was growing, my attention was caught, and I was trying to understand why there was this barrier. So it took me a long time, and when I grew up, I became 24, 25, I started my own research. I worked by myself in a camp when nobody else was around. So I spent six months with them to understand exactly what was going on. And when I came back to my country, I started to teach my people, people my age, to change their attitude toward pygmies. But it's not over yet. We are still going. It's a struggle. Because people are still keeping the same attitudes.

B.E.: That's fascinating. I'm interested that you learned to speak Diaka, and that that is unusual. Am I right that this is not the typical relationship between Bagandou and BaAka?

J.M.: No, my case was unusual. Very unusual. Even now people my age cannot speak Diaka. They see Diaka as a very low language to speak in public. So I was very lucky to learn that language. Sometimes when I look back I laugh, wondering how I made it!

B.E.: Fascinating. If we were to speak more generally about the relationship between the BaAka and their neighbors, how does it work? Michelle, in your book, you use the phrase “their bilo” referring to the neighbors. It sounds like almost an ownership relationship. Can you decode this relationship for us a little bit?

M.K.: Yes. It's complicated because there isn't a one-to-one correlation with any relationship that any of us know in America, for example. It is somewhere between a family relationship, and a patron-client relationship. So there are parallel clans. A family of Bagandou people will have a parallel clan of BaAka that they are associated with, and some families may have more of a positive interaction, a familial one, where they help each other in different ways depending on their areas of expertise, and in other cases, perhaps more commonly, it's more of a relationship of domination where BaAka are expected to serve their Bagandou milo [plural is bilo], and are considered really lowly in their presence. An insult that a Bagandou parent might give to a slovenly child might be that "you're acting like a pygmy, a MoMbinga.”

B.E.: So these are sort of clan-to-clan relationships, where one Bagandou clan has a relationship with a BaAka family. Do these relationships go way back? How are they established?

J.M.: Ah, in my case, I started to know that my people and pygmy people both were members of the same group, Bombolongo. I didn’t know until I grew up that my relatives are Bombolongo, and in this sense were “related” to the Bombolongo pygmies. The relationship was not balanced. My people, Bantu people, didn’t treat their so-called Mbolongo with love and respect. That was the most shocking thing to me, as a young boy. This was where my dream to intervene started, so eventually I did.

M.K.: And if I can add, you asked also about forging new relationships, I saw cases where there would be BaAka who just really did not like their associated clan bilo (villagers), so they would just simply go to an area that was not within the purview of their bilo, and associate with another group of people, and either not have any ties to bilo directly or forge a new relationship. But it would not have the same kind of overtones or obligations as do the parallel clans. So they have ways of avoiding unpleasant relationships to some extent, or even leaving altogether and going to a different area, such as crossing the border into the Congo.

B.E.: So the villagers are more sedentary, and the BaAka more mobile, right?

M.K.: Yes, although BaAka also have their traditional territories as associated with their bilo, which is Bagandou in some cases, and other ethnic groups in other cases.

B.E.: I see. So they are not just purely nomadic, going wherever they want at any time.

M.K.: That's right. They have long-term traditional territories that they migrate within.

B.E.: Is there any advantage to this relationship from the point of view of the BaAka, the forest people? Do they get anything out of it?

M.K.: Oh, they do get things out of it, depending how skilled they are in manipulating the relationship. They can sometimes get Western medical care. It may or may not be what they need, but sometimes they need penicillin or something like that. They get Western clothing, which they like for a status symbol and for other reasons. Shoes, cigarettes, pots, women's cloths, hatchets. What else?

J.M.: I think these last few years, we are trying to teach them to write and read in French. It will take another decade to get everybody involved in education system. So I think that step-by-step we are trying to help them understand our side, because they know their side, but they have to read, to know, so that they can keep life going the way they want to.

B.E.: When most BaAka can read and write in French, that will change their lives quite significantly, won't it? It will change their options, and make the world quite different for them.

M.K.: Yes. And also, being able to count, able to control counting and the exchange of money, because often they are cheated terribly in economic exchanges because they are not oriented to that system.

B.E.: At the end, we'll come back to the changes that have happened, but I want to go back now and talk about the whole domain of participation and apprenticeship. Michelle, why was it important to you to learn to perform these songs and dances rather than just study them?

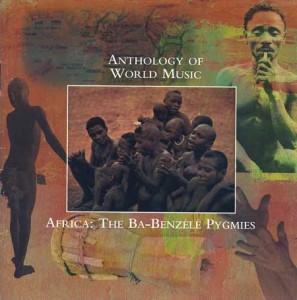

M.K.: It was important for me to learn the songs and dances as part of the research. It was central, in part because the reason I was drawn to African music in the first place was through participation. The first African music that I learned was Ewe music from Ghana and Togo in college from Prof. David Locke, and that taught me something profound about what participation can teach you about other sensibilities and about yourself. I first heard BaAka music recorded by Simha Arom. There is a famous recording that he made in the Bayanga area that was highly influential. It influenced Herbie Hancock, Zap Mama, many other people starting in the late 60s and 70s. But when I heard that as a student, it so completely overwhelmed me with its beauty that I thought (and this is at the same time that I was learning West African drumming and dance), that I thought "Well, if I could learn how to participate in this even just a little bit. If I could learn how it works enough to be able to join in, then I would have spent my life well."

I wasn't at all sure that this was a possible thing to learn, but I really wanted to try. I did not want to be the kind of researcher and scholar who goes somewhere to study something from a distance and then tries to analyze it and represent it. I wanted to go in and have first-hand experience, as a performer, and as a human interactor, getting to know people, becoming friends with people, being fully involved in life in as positive a way as I could. I wanted to make sure that it wasn't a negative or neocolonial kind of relationship, that was my intention. I would not have gone had there been no possibility of trying to engage in that kind of a way.

B.E.: Which was that Simha Arom recording? Is it available?

M.K.: Yes. It’s the Anthology of World Music. Africa: The Ba-Benzele Pygmies (Rounder, 1998, 0 11661-5107-2 2)

B.E.: Let's come back to your apprenticeship. I want to talk about questions of payment and compensation. These things posed a challenge for you in your various mentoring relationships. Talk about how you negotiated these understandings.

M.K.: One thing I needed to learn when I initially went to the Bagandou region for the first time was how to compensate people for the help they would give me or the instruction they would give me. And at first, I was told that the standard way for outsiders to compensate the BaAka was through cigarettes. [stick, baton] One cigarette for one thing, two cigarettes for another. That was also a mode of exchange that Bagandou would have. For example, a MoAka—that's a singular for BaAka—might come with a whole leg of a duiker [antelope] to offer a villager, and in return he might get a cigarette. It's not really a very equal exchange, but many BaAka are so addicted to tobacco, and probably to nicotine—because there is extra nicotine in these French manufactured cigarettes that are distributed in Africa—that some people will do almost anything for cigarettes.

I myself have a real distaste for cigarettes and cigarette smoke. It runs in the family. My grandfather died of emphysema. My mother is allergic. I can't stand cigarettes, so it was really hard for me to participate in this mode of exchange, but the first month or so, I did, because I wanted to conform to the local custom. But I decided that when I would return for my long-term research, that I would establish a different kind of system. So right away, that set me up for a little bit of a conflict. Justin thought that the BaAka would not cooperate at all with me if I did not offer them cigarettes, but I held fast to my conviction I guess I would say, and offered different things. I offered oil for cooking. I offered pots. I offered sometimes hatchets, cloth, and things that I thought would help people, not that I thought would hurt them. And Justin taught me how to explain that cigarettes make you sick with coughing, so I don't use cigarettes, but I use other things. And that caught on to the point where I was known as the person who doesn't offer cigarettes. And one time I was walking down the village road with Ndanga, a MoAka who is from the camp that I was living in for a long-term period, and a villager called out from his veranda, "Oh, you are walking along with a white person. She must give you lots of cigarettes." And Nganga answered back, "No, no, no. She doesn't give cigarettes. They make you sick with coughing." And that was the moment where I thought, "Yes! I have succeeded."

B.E.: Great story. Now, compensation issues also rose among the BaAka groups you work with, for example when the Kenga BaAka came to be initiated in the dance called Mabo. What do these negotiations and impasses tell us about what you call the “shifting economic base of BaAka life”?

M.K.: Yes, exchange. The worth of music and dance and economic relationships are extremely revealing and extremely complicated to understand. One case was when an extended family from Kenga, which was sort of a sub village of Bagandou about 15 km away, came to be initiated or inducted into Mabo, the hunting dance that was current at the time. And in the camp where I was living were the masters of that particular dance. So the Kenga BaAka came to my home camp to be inducted or initiated into Mabo so that their hunting would be more effective. That is part of the connection between the dance and the hunting, is that it makes your hunt more efficacious. So the idea is you have to give up something in order to get inducted, because you're getting something very valuable, both culturally in terms of beauty, but also in terms of your economic well-being, your success in the hunt.

But there was a bit of a conflict about what the payment would consist of and how extensive it needed to be. So the BaAka from Kenga came with a hunting net, which would be sort of a traditional thing that one would offer, a traditional object of value that one could offer in exchange. But Elanga, who was the elder man in the camp that I was living in, was disdainful that they didn't bring more. And he actually set out on the ground some things that they had brought, which included an almost finished little piece of soap. Now soap is valuable, but it was almost completely used up. And he was sort of criticizing. "Look, they just brought this little piece of soap and this hunting net. We need more." So the BaAka of Kenga ended up leaving without any of the Western clothing that they had come with. The nice sweater that Mabambo had come with ended up on the shoulders of Sandimba, who was in the camp that I was living in. She was kind of my BaAka mother. She taught me many things and took care of me quite a bit. And everyone else too left just in their loin cloths, when they had come adorned in their best Western clothes that they had earned from working for villagers.

But they weren't too happy. They didn't think it was fair. They thought that Elanga’s family had asked too much. They also thought that they had spiked the medicine that went into the eyes of some of the initiates. It is medicine that you put into the eyes to see better the game while hunting, and the Kenga BaAka thought that they had spiked this medicine with hot pepper to make it more painful. But the dance leaders, the men who had inducted them, said, "No, no, no." That's exactly what they had had when they were inducted in Congo. So there is a lot of conflict and controversy that keeps them alive socially, but could boil over into harsher sort of unhappiness and conflict, but didn't while I was there. But clearly it evidenced a sort of change in the level of expectation of what the worth of a dance is, and how much you have to pay for it

B.E.: So that kind of spiritual commodity is not precisely valued, and in a world where more and more material goods are coming into play, it becomes part of an active negotiation. Certainly that was the case in the time that you were there. Is that fair to say?

M.K.: That is fair to say.

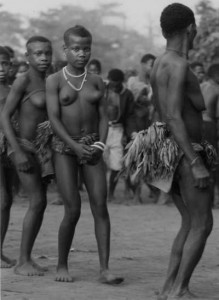

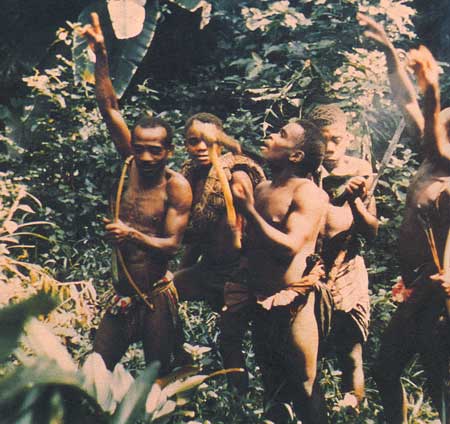

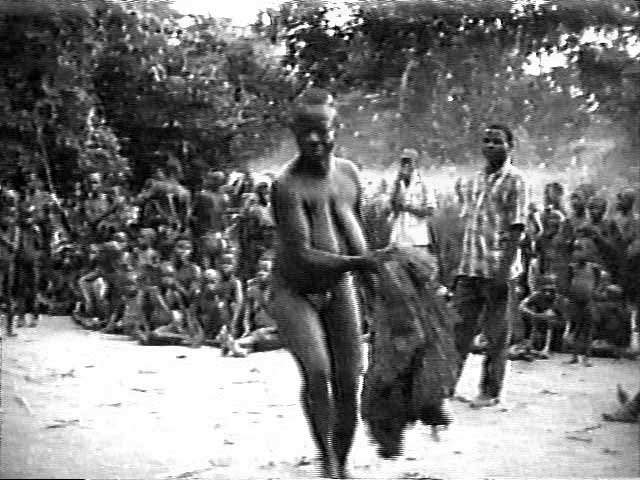

B.E.: Let's go more deeply into your experience. Describe the initiation you underwent in order to dance Elamba, a women’s dance.

M.K.: Okay. When I first started to spend time in the BaAka camps, Justin and I traveled to Ndanga, which is about a three-day trek into the forest, and we stayed there for about three weeks. I really wasn't sure where I was going to focus my research, or if I could focus my research. But one day there was a tragedy in the village. A little girl who had been sick died, and that night, there was a funeral dance. Now at a BaAka funeral, and at most traditional funerals in Africa, the people who are most directly affected are in deep mourning, and will be crying. They will be in mourning, but the rest of the community will come together and sing and dance to celebrate life in the face of death, and to keep the spirits of the people in mourning high enough so that they don't themselves want to join their departed relative, because they are so depressed and down. So the idea is to keep them focused on life, and also to send the spirit of the departed into the world of the ancestors. In the case of a child, for BaAka, the idea is that a child's spirit will actually return in another child. So rather than going to the world of the ancestors, they actually come again in another baby. But in any case, the community came together with a dance that night for this child who had passed. And it was heart rending. The mother was sprawled on the grave and crying, and milk was dripping, and I had never seen anything so sad and immediate in terms of death. And that affected me also.

But that night, all of the women performed a women's dance, which had two parts. One was Dingboku, which is an opening dance that all women can dance if they know the dance. And it is lines of women, short lines of women moving back and forth. And then a second dance that comes after that introduction called Elamba, which is more of a solo dance, although you can have several soloists dancing at the same time. And that dance, I learned later, was just for women who had been inducted into Elamba.

The singing was wonderful, and I felt at that moment that this was where I wanted to focus, on the women's dances. Justin didn't even know that they existed. He had spent a lot of time among BaAka, but he had never focused so much on the particulars of dance, and he never realized that there were these women’s dances. So that was a big discovery for me that night, and I vowed to go as far as I could in coming to learn the songs, to learn the dances, and then I found out that you had to actually be inducted in order to perform the dance. So when I lived for a long time, in the Ndanga camp—I came back to that same camp that was the three-day hike and lived there for quite some time—I tried to find out how I could perhaps be inducted. That same group of people later in the season moved next to the village for the coffee harvest, and I joined them there next to the village as well. And I tried for some time to see if the mother of the dance, whose name was Djongi, would induct me. And she would say she would, but then she wouldn't do it. She was very evasive, I would say.

But then I asked Sandimba, who I had a much better relationship with and who was my next-door neighbor in the camp, and she was sort of a cultural maven, really a very, very strong woman, and a very funny woman. She had seven children. She said that the real mother of the dance lives across the border in the Republic of the Congo along the Oubangui River, in the village of Mopoutou, and that if I really wanted to get inducted, I should forget about Djongi, the local mother of the dance, and go to Mopoutou to be inducted by Bongoi. And everybody knew about Bongoi. They hadn't met her, most of them, but they had heard of her. And Sandimba said that she was even planning to make a pilgrimage to Mopoutou to be inducted, and that this was going to happen fairly soon. And I waited for a while. It never happened. And actually, both Sandimba and Bongoi died before Sandimba ever made that pilgrimage. A few months later, I just decided to take it upon myself to go to Mopoutou, and see if I could get inducted. I actually ended up going twice in that direction, once by boat, and once overland. And I was inducted.

B.E.: The descriptions of your journeys to the Congo are quite incredible. But tell us a little bit about the actual induction.

M.K.: Yes, it was an arduous journey getting there, but when we finally did get there and met Bongoi, she offered to induct me. Now she had just lost her daughter in childbirth, which is the worst kind of way, of course, to lose anyone; she had lost both her daughter and her grandchild. So she was unable to be very active in my instruction, but she was able to induct me. And her husband also helped me, and participated in this. He was very supportive. So the induction consisted of little razor cuts. I didn't really know this until it came the time. Tiny little razor cuts in the back of the neck, on the shoulders, on the back of the hips, on the back, rear side of the knee, and on top of the foot near the big toe. And the traditional practice in this whole area is the idea of sort of a traditional vaccination were you make little razor cuts and rub in a medicine, and the medicine could be a number of different things. In this case it's a powder made of special trees from the forest. This is meant both to make you able to dance, and limber in those spots, and also to protect you from envious people, or other malevolent forces that may harm you. Because when you are on the spot in a solo dance, you are much more vulnerable to jealousies and other things. BaAka generally have an attitude that Barry Hewlett, an anthropologist, put as “prestige avoidance.” Obviously, dancing solo in front of lots of people could gain you prestige, so you have to protect yourself and sort of even things out through this induction. It protects you from the ill effects of prestige.

So I decided to go through this. I was a little leary. People were especially concerned that the little bit of blood that came from these little cuts would not be seen as going into the hands of any perhaps malevolent sorcery type activity, so they disposed of the tissues. We had tissues and were wiping the blood, and they burned these right away and in front of us. And Bongoi’s husband made a point to say as we were leaving that if anything happens to me, it's not because of this. There was a lot of concern that they could be blamed if something bad were to happen to me and it would be attributed to this. Because that does happen. They do get blamed for things. So he really wanted to be sure that such a thing would not come back to them.

B.E.: Once you had had that experience, then when you return, you are eligible to be taught to dance. Is that right?

M.K.: Yes. When I returned to Bagandou and Justin and I explained that I had been inducted into Elamba, all of a sudden, people had a very different attitude towards me. All the women and girls gathered around me to see the marks where I had been inducted. It was at sunset, so they were sort of squinting to see the marks and all of a sudden they were treating me quite differently. If they were to be sitting down, let's say on a log, and I were to cross that log. Everyone would stand up briefly and then sit down again while I crossed. I was very confused about that. Why are they sort of bowing? What is that? And Justin explained to me later that this is a way of avoiding... The power that one gets from the inducted could inadvertently affect someone else in a negative way if they were to disrespect me. So if someone didn't see me crossing the log... and at one point this happened. She didn't stand up when I crossed, and then she said, “Dzangela ame” (“step on me” symbolically). And I didn't know what she meant. And so she took my foot and she made me step on her foot to even out the offense. I had to step on her because she had inadvertently “stepped” on me by not standing up when I crossed the path.

So all of a sudden I had this mystical power that I didn't really have a handle on what all it meant. But it allowed for BaAka taking my interest in the music and dance much more seriously, and kind of accepting me at a level they hadn't before. They had always been friendly to me, but now they seemed to see me more as one of their own. But of course then they expected me to dance. And I didn't want to dance yet. I hadn't even learned how to dance. I had only seen the dance a few times. So they were confused when I was reticent and wanted them to dance first. So there was a moment of confusion at that point. But eventually, I did dance. And I heard the rumor later... I heard someone saying to someone else that they had seen me dance and I danced well, so I was happy that that had been the rumor that was circulating after that.

But that was the Elamba dance. I had danced to the more general dances that you don't need to be inducted into to participated in. I had also waited to be invited to dance, because elsewhere in Africa I had been invited. I didn't want to impose myself, and people usually invite me if they want me to dance. But BaAka are different. And Justin's uncle, when I said that, explained to me, "Oh, no, no. BaAka would just assume that if you wanted to dance, you would get up and dance." And this is also connected to them not wanting to be blamed for something bad, because if they had invited me to dance and I had gotten up and then something bad had happened to me, they might've been blamed by Bagandou for having mystically done something to me. I did get up and dance Mabo, and then afterwards, again, the next morning they wanted to be sure that I was okay and that nothing bad had happened to me that they might be blamed for. Because it circulates among Bagandou that a MoAka can sort of mystically touch you while you're dancing and then do some harm to you.

BaAka are feared and admired for their mystical (and healing) powers, even though they themselves don't see themselves as doing anything malevolent. They are seen as being powerful in that regard. They can make themselves disappear. They can turn themselves in to elephants. That kind of thing.

B.E.: I understand the fear of being blamed, or held responsible, if something bad happens after they have initiated some activity on your part. But the fact that you had to overhear a rumor that people thought you had danced well seems like something different. What's going on with that reluctance to praise?

M.K.: That's an interesting question. Because in Elamba there is a kind of praise that goes on in the dance. If a woman is dancing well, other women, or even men, or even non-BaAka if they are there, can come into the dance circle, interrupt your dancing, raise up her hand, or press some money against her for head, or offer her a gift that her relatives might run in and collect so that she can continue her dance, but I don't believe... it may be a blur, but I don't believe they ever did that to me, which would have been a more direct way of acknowledging that they thought I was dancing well. But I think they weren't really sure of me is as yet, or sure it would be taken positively if they were to intervene that way. I actually am not sure what to conclude about that.

B.E.: Fair enough. Let's go on to talk more about the music itself and how it reflects BaAka social organization. You write about “the individualistically egalitarian social life that BaAka usually maintain.” You also write that “An egalitarian sensibility makes for a cultural climate of constant negotiation.” Tell us about these dynamics, and also tell us how they get expressed in music and dance.

M.K.: The way I think about it is as a real refinement and honing of the sensibility of collectivity through individualism. So it's the opposite of conformity, but it's what you need in order to have a strong collective, to allow for individual personalities and voices to work together. So it's a kind of a flexibility that allows for the collective. If somebody is kind of too individualistic, then they move outside the collective and they're no longer in it, but what BaAka know in general quite well is how to be themselves in a group. And the music works very much that way. You are listening in an extremely fine way to each other while you are expressing your very particular voice within the group sound. Or in relationship, in reaction or response to the group sound. And every once in a while, some people will sing a line or two together in unison, but then they’ll break and go their own way as they are listening and interacting in very intricate ways with what they are hearing and seeing their relatives and friends do.

B.E.: Well put. Let's talk about how songs are put together, starting with the basics singing style, how a single voice sings. After that, we can look at how parts go together to make a song.

M.K.: Sure. Well, two of the things that pretty much immediately identify BaAka or forest peoples style are the syllables “Ee Ya, Ee Ya” sometimes “Oh. Ee Ya Eh.” Very few actual words for the most part are involved in the singing. Especially as the songs get more elaborate over time, that text drops out. The words drop out and are replaced by “Ee Ya Ee Ya Eh.” That's one thing. The other thing is yodeling. So those are two identifiable aspects of BaAka singing style. It has to be loud to come out the right way.

And I should say that when I told Justin that I wanted to learn to sing like BaAka, he laughed and thought I never would be able to. And he said he would get a goat for me and have a big feast if I ever did. And one day, nearing the end of the two-year period that I had initially spent in CAR, I was at Justin's farm and I was just taking a walk in the woods nearby and I was singing and practicing, listening to how my voice would echo back to me from the forest canopy, because that's a real important aspect of BaAka singing. You are listening to your own voice echo back, and kind of singing with your own voice at the same time as would other people, if there are other people there. But when I came back, I learned that Justin's great aunt had heard me singing and was wondering who these BaAka were that were walking by. So I thought, "Ah, I finally did it." For Justin, I had done the impossible which was to learn how to sing more or less like BaAka sing.

B.E.: And was the goat forthcoming?

M.K.: No, the goat was not forthcoming. [LAUGHS] He still owes me that goat. Although he has cooked many a goat for me, he has not actually purchased and killed a particular goat. So anyway, a phrase that might be part of a song, like this Mabo song. [SINGS] And then, if someone is singing a lullaby, they might drop out of the metrical pulse and just get the baby to focus on something other than what they're crying about.

B.E.: I want to talk about the teaching process, but you mentioned Mabo, the hunting dance, so let’s start with that. Tell us briefly what a net hunt is like and how the singing and dancing goes with it.

M.K.: Yes, maybe I can share that description with Justin because he's been on a lot more net hunts than I have. But I can talk more about how I see the relationship between the form of the dance and the hunting activity.

B.E.: Great. So Justin, what goes on in a net hunt?

J.M.: The hunting system is kind of a game organized among many people. They will go a distance, a long distance. Maybe four or five km apart. And somebody would have very strong voice will be leading other people to get in order, so they can make the hunting successful. The nets are set up in a semi-circle. Then somebody with a loud voice will sing so that other hunters can get connected to what is happening, but without scaring off the animals.

M.K.: Do you want to give an example of the kind of call?

J.M.: They will say, [SINGS]. My voice is not that good, but they call this mongombi, and it takes like a male voice to express the power, the male power. Mongombi can go so low. It can be for hunting. Or it can be when you go looking for honey. So it is the way men express themselves. And your wife can hear you, even if you are distant, she can hear you. She can identify your voice. But in a collective hunting system, there is somebody who has a very strong voice who will be leading all the day. Because they have to go one section, and then take like a break for like 30 minutes, but people have to get them together so they start a new one, so there is always somebody in the group who is like a leader of mongombi.

B.E.: What exactly are they hunting? And how does it work?

J.M.: There are many types of hunting. The common one is with a net. They will use a net, so somebody can have like three or four. Wealthy people they can have more than four. And with all these nets, they can go around and make a circle, and people will be in the middle of the circle to sing and to make the animal run into the net. This is what we call bogia, net hunting. Sometimes they can go just with spears. Bogia, with the net, includes women and men and sometimes teenagers. But when they go hunting with spears, only men can do that. And they call it mangosso. That's where my name is from. My name is Mangosso, but with French they say Mongosso.

B.E.: How big is this net?

M.K.: Justin, one would be how many meters?

J.M.: I think they have different sizes. They can have a long one that can be like 50 m. Some can be 10. Some can be even 2. So they're different sizes of nets they use.

M.K.: Right. And then they'll link them together to make a really big semicircle. And that can vary—how big it is depends on how many people are involved in the hunt. There may be three nets. There may be six nets.

J.M.: And sometimes they can use a very small nets to catch porcupines. So that's another type of hunting.

M.K.: Usually they are hunting for duikers, or antelopes. So blue duikers are really common, the little duikers (called mboloko). And mosome, the medium-sized ones, and then bemba is the large duiker.

J.M.: They can catch any animal. Sometimes they catch a panther. They can catch any animal that goes into the center.

M.K.: So the way it works is in cycles of setting up the nets, shouting and singing to scare the animals or wake them up and have them run into the nets, and then resting before another cycle. This is parallel to the cycle of the dance, the Mabo dance, where the dance will warm up. There will be some songs. The dance will get going. And then there will be an esime, the “get-down” percussive section where the singing stops and people will call out percussive calls that are very similar to the shouts and calls that are used in the net hunt. And then another cycle. They might stop and rest, or they might go straight into another song. And part of the dance is the mask, which is controversially embodying forest spirits. Some people say yes, some people say no. And part of the thing that keeps it alive is this discussion as to whether there's really a spirit in the mask or whether it's just a person inside a bunch of leaves. One person inferred that it was game hiding in the forest thickets. So the mask is spinning and shaking and sort of symbolizing the life that is in the forest, the bounty of the forest.

B.E.: Now is the dancing and singing going on at the same time as the hunt?

M.K.: No, no. The hunt, that's the work, during the day when they’re deep in the forest and just focusing on the hunt. But there will be a rest period where there'll be some singing. People will rest and have some snacks and sing, and then go on another round of hunting. But in the evening the dance, which sort of mimics the form of the hunt, will take place. But they don't happen at the same time. But they may happen in the same period, like the hunting during the day and the dancing in the evening to make the hunt more efficacious, and to celebrate whatever it is they've caught that day.

J.M.: The dance and the mask take place at home in the camp. It can be in the daytime before hunting, or at night.

M.K.: And he was saying bokia is the word for net, and dibouka is the net hunt. So the word dibouka means net, or net hunt, while the word eboka means a dance event. I believe the roots of the two words are related (bouk/bok).

B.E.: It must be quite an experience. When the hunt is actually happening and they are shouting to scare the animals into the net, is that one person, one man doing that shouting and singing, or could it be a larger group?

M.K.: It's a larger group. There are basically two groups on the net hunt, the people who guard the nets—and that's either the women and children or the men, one or the other doing that role. So let's say the women are guarding the nets. The men are out, way out beyond the semicircle, and they will all be shouting and also have branches to be hitting the leaves to scare the animals, so that'll be quite loud. And then sometimes they'll change roles where the men will guard the nets, and the women will shout and shake the branches.

B.E.: I would imagine that the moment when a big antelope runs into the net must be quite dramatic. If you have women and children on hand, are they actually able to control the animal?

J.M.: Guarding the net is very, very dangerous, and most of the time it is causing too many accidents.

M.K.: Injuries. I once saw a woman who had been gored through the cheek with the horn of an antelope.

J.M.: Some animals can bite or hurt somebody. You have to be careful, approaching or catching them in the net.

M.K.: And there are special charms and medicine that is used on the nets as a protection.

J.M.: And also so you can master what's going on, so that your vision goes beyond your body to see what is normally unseen. But it is a very dangerous activity, but they get used to it and it's like part of their life, but sometimes it causes terrible accidents, even fatal ones.

B.E.: So what is the technique for actually killing them all once it is tangled in the net?

J.M.: Okay, if the animal is caught, the lady or the youth will grab it, and the men will come with a big knife to cut its throat.

M.K.: Or something they'll club it, or, if it's a small duiker, they will pick it up by the hind legs and hit its head against a rock. This was hard for me to watch but it is part of survival for BaAka. Anyway, the word “pia,” which is "grab," like you grab an animal in the net, is the same word for starting up the dance. “Pia eboka” we’re gonna start up the dance. So there's a parallel there. To grab something is to get something going.

B.E.: And that's where the title of your book comes from, isn't it?

M.K.: Indeed. To seize it, to grab it. To seize the dance, or to seize the animal. And one other thing, another skill that the BaAka have, a vocal skill, is imitating the sounds of an animal, so that can also lure them into the net. BaAka are good at copying the sound of a duiker in distress, and another duiker might come. Is this correct, Justin?

J.M.: Yes. The hunters use these techniques when hunting with a spear or gun, for example on commission for a villager who owns the gun.

B.E.: That's fascinating. Dramatic stuff there. But let's come back to the music now and talk about the singing that goes with Mabo. You describe this singing in one song, Makala, as "freewheeling." What do you mean by that?

M.K.: What I mean by freewheeling is that everyone will have a basic cycle—the cycle of the song—in their ears. And once they're familiar with the song, they can improvise around that basic theme that repeats. This is a common aspect of African music. BaAka have really honed this to a fine degree. But the same phrase will be in people's minds, and they will be able to elaborate on that phrase as they become more comfortable to the point where the phrase itself is often not even audible directly. And people are improvising all around it, and interactively. So when you hear somebody next to you sing [SINGS], you might sing [SINGS VARIANT PART]. So that's what I mean by freewheeling as being interactive on top of this loose structure of the melody of the song that repeats in the cycle. And there are polyrhythms, poly meter going on beneath all the time. [CLAPS TWO AGAINST THREE]. So the twos and threes are underneath this all the time. So you never have just a single beat. You always have the second beat being felt underneath it, whether people are clapping along with that, or if the singing is articulating different versions of twos or threes.

B.E.: Maybe this is the time to talk about teaching, and how you teach this music. You as a Western person are dedicated to the idea of imparting this knowledge to other Westerners. How do you approach that?

M.K.: Well, I slowly learned how to teach what it was that I had learned. In writing my book, I had to listen much more carefully to my recordings to understand how many parts might be possible at a given moment of articulation of the song during a dance. So part of it I learned by going back to recordings and listening. I had learned some basics while I was there, and could chime in, but when I wrote the transcriptions, I listened even more, and learned even more parts. Then, when I had my first teaching job, I was committed to teaching in a participatory way, just as I was committed to learning in that way. So I sort of experimented with how to teach these songs in a way that would convey BaAka style. And it's tricky, because people come in with their own habits, musical habits and experiences.

I started by teaching a central phrase or something that I would identify temporarily as a central phrase, something like [SINGS "BAKELE"]. Just that simple short phrase. And I would teach people to add the different parts that I had learned. Now the tricky part here was people tend to just repeat whatever they've been told to repeat, and then they won't be listening or being interactive or freewheeling at all. So my argument to myself about that was, "Well they might be learning to sound a little bit like BaAka, to the point where BaAka could recognize the song, but they wouldn't really be singing in BaAka style, because they wouldn't be musically and socially interactive." So people have to become familiar enough with the cycle and its overall shape and harmonic relationships, and being free with a sense of poly meter, that they can then play within those cycles and interactively respond to each other. And it can take quite a bit of time depending on the sort of musical background or lack thereof that the people who are learning have. But it seems to work pretty well.

Now what happens is, in any group that I'm teaching, people sort of come out with their own style, and if they're learning from me, it has a certain similarity to it that I actually wish would be a little bit more varied. But over time, it does vary. When I compare something that I taught seven or eight years ago to the way my students are singing now, it does change. Because I remember it differently, and I start to develop my own style within it. And that would be a BaAka way of doing it, because in a different village people might be singing the same song, but singing it in a different way. And we can find examples of that, how one song is sung in one place as opposed to another place.

And also, over time, the song might sound very different. When I returned to CAR, to Centrafrique in the year 2000, and then again in 2007, the people I knew were singing the same song quite differently. Both because it was different circumstances, and BaAka sing in according to their circumstances. There isn't sort of a set idea of a piece that they then repeat the same way all the time. Their sound reflects the moment, who’s there, what's going on in people's lives, and that's what I love so much about the music. So this variation is part of what the style is all about. So that's the challenge to really teach, and I call that the "it." I wrote a piece with one of my students, Kelly Gross, called "What's the ‘it’ that we learn to perform.” And we’re asking that very question. Is the "it" the sound? To imitate the sound as best we can from a recording? Or is the "it" this freewheeling interactiveness that may come out sounding rather different, but is still identifiable stylistically.

B.E.: Give an example. DJ it. We'll find the music later.

M.K.: I think I will pick “Bakele,” because there are two versions right next to each other on the CD. Or on the website. Okay, so these two recordings of “Bakele” were made on different days. The weather was different. One, it had been raining and it was later in the day. And the other, it was earlier in the day and it was sunny, and people were more energetic. And when I recorded the song during a dance, it was closer to this version of it. So you can hear Kwanga is opening up the song, and you can hear [SINGS MAIN PART]. And in the second version, you can hardly hear that [SINGS MAIN PART], which I had identified as a kind of core theme. But the core theme can shift over time and circumstance as well. So the second version, you might think of it as kind of in a minor key, even though the pitch relationships are complementary, the emphasis is different.

B.E.: Tell us a little bit more about the circumstances of the second version.

M.K.: Okay, this day it had just rained, and people were gathering together at the tent site that Justin and I had set up. This was fairly early on in my research, when I was feeling like I was just apprenticing myself to the singing. I had not yet been inducted. And Djongi and some of the other women and children, and a couple of men, came to sit on the bench that Justin had built in front of my tent. And you know, it was soggy. It was a little cold. People were tired. They hadn't found much on the hunt that day. And this is how it sounded.

B.E.: Perfect. Before we move on to discussing changes in contemporary times, tell us a little more about about women’s music and dance, and about the nature of gender relations among the BaAka generally.

M.K.: One thing that attracted me to forest people in the first place was the suggestion by Colin Turnbull, and by the famous Alan Lomax, who pointed to pygmy singing style as an example of an art form that comes out of an egalitarian lifestyle... Often, by egalitarian, people mean sort of politically egalitarian between men, but my assumption was that this is also about gender egalitarianism, and in fact it was. And Colin Turnbull implies this a bit as well. Even though there are some separate kinds of things that men and women do, there isn't a hierarchy placed on men's and women's activities, men's activities are not more prestigious.

Now, when BaAka are living close to the Bagandou village, or closer to the farmer's villages, these dynamics tend to change. All of a sudden, male roles become a little bit more domineering, and the men seem more threatened by the women's assertions of their autonomy. So this dynamic would change. When the BaAka were further away from the village, there wasn't this kind of tension. There was more of a supportive relationship between men's and women's dances, and when they would dance together. Nearer to the village, when BaAka were dancing Dingboku and Elamba, some men would get frustrated and want to intervene and have their own dances. Others would actually interrupt the dance or come into it. Normally someone would come in and honor the dancer. There was a moment when one, somewhat drunk MoAka came in and mooned the crowd, and instead of honoring the dancer, sort of wagged as tushie at everybody. And the women were shocked, and so were the men who were supportive of the women. They were not happy with that, but they didn't come and push him away or anything. The dance just continued. Actually, some women and a man came in and, within the dance, defended and honored the dancer in response to this mooner.

But I saw this as a barometer. I saw these women's dances as a barometer of gender relationships. And these gender relationships indicated whether or not there was tension or other types of stresses that were placed on this BaAka community, usually by their Bantu neighbors or by the missionaries (but sometimes simply because the hunting was not good and people were hungry).

B.E.: What are the circumstances that might make for greater tensions between the genders?

M.K.: There would be more tension when the men were spending more time in the village, and being paid in alcohol for their work for villagers, in corn whiskey. So instead of coming home to the camp with meat, which is the normal thing that would give a man prestige, they would just come home drunk and have nothing to offer. And then the women would be unhappy. And then fights would break out. The other big stressor in my time was the relatively new presence of missionaries from the Grace Brethren Church, who were introducing some conflict among BaAka—those who were wanting to follow what the missionaries were saying, and those who were not. The missionaries were also demonizing BaAka music and dance in a way that made people say, "Oh, we are being satanic when we do our traditional dances, so we had better stop.” Other people arguing back. So that was another level of tension. Justin wants to add something.

J.M.: Pygmy people live in harmony with themselves and with nature. Among pygmy people, gender does not matter. It is totally different from here in Western civilization. That does not work in pygmy social life. Because everybody is himself. The man will be himself. The lady will be herself. But they work hand-in-hand. By knowing themselves, I don't think they have these conflict that the man will think his wife is trying to take over. Or the wife will think her husband will take over. But I think the vision, the way western people think, goes beyond... I don't agree that this conflict exists in pygmy life. I don't think so. It's all as the religion, because people think they don't know God, but it's wrong. When somebody from here, like a western person—it can be a man or lady—is among pygmies, that person will see things differently. He or she will assume things that I think doesn't exist. So I think it's a little bit complicated to go deep, to understand what they think, or what you think yourself. Gender does not matter for BaAka.

M.K.: But this happened when I was living with the BaAka. I was observing this when you [Justin] weren't there. There was a difference between how they were in the forest and when they were near the village. A very marked difference in how they were relating to one another.

J.M.: I know when somebody is drunk, he can’t control himself. But it does not mean he's the same way when he is not drunk. Sometimes when pygmies are intoxicated they behave badly. But naturally they are the most harmless people in the world.

M.K.: Well, yes, but I want to interject that this sort of Edenic idea about BaAka spreads to Bantu neighbors and others. And it's true that relatively, they live in egalitarian harmony. But this idea that they are always in harmony is kind of a blinder too, because they are like any other people. They are negotiating their lives in a moment to moment way, and they deal with stresses, and their music and the dance is really indicative of whether there are these stresses going on, and in what way they are being manifest. And they are actually aware of negotiating these stresses and dealing with them. And they work on getting rid of them, to an extent. And music and dance helps in this process.

B.E.: Justin, what I hear you saying is that inherently, they do live in harmony. And Michelle I think that what you're saying is that this whole situation, particularly this artificial moment when they're not in the forest hunting, and they are interacting more with the villagers, kind of distorts or corrupts their natural harmony. But that this is all just part of the complexity of their lives, living in these different environments, and having to adapt to these different situations. It disrupts their natural harmony. Is that a fair synopsis?

M.K.: Yes, but I would be careful of using the term natural. It's a very sophisticated cultural set of skills that they have developed as a people over a long, long period.

B.E.: Natural is a loaded and vague word. I understand.

J.M.: What I was trying to say is that when somebody is intoxicated, he can harm himself or others. So you have to see when he's drunk and when he is not drunk. Maybe he's facing a problem. But generally, they live in harmony with themselves. I don't really think that there is a problem where a pygmy women will try to transgress her man. Or a man will try to do that. They respect each other. I really admire the way they live. They live with love for others and for nature.

M.K.: Yes, but it's different from how their neighbors live in terms of gender distinctions. For example, I saw Sandimba lead the net hunt once. Djolo, her husband, stayed home and watched the grandbabies, while Sandimba led the net hunt. I don't remember why, but there was no apparent stigma about that being a manly thing for her to do, or a womanly thing for him to do. And one time, a man came back to the camp really sad because there was nothing to eat. His wife hadn't prepared anything for him. She was highly pregnant and very uncomfortable, and hadn't made anything. And I asked him, "So why don't you just make it yourself?" And he just said, in a tone of voice that was very much feeling sorry for himself, "But I don't know how." So it wasn't that it was below him to cook. He just didn't know how to do it.

B.E.: Well obviously, this is complex territory. But before we leave gender relations, I just want to ask you, Michelle, to explain the Dimboku track on the second CD, “Ame Ote.” Just give us a little introduction to that song.

M.K.: Okay, so Dingboku is the women's dance that is used as kind of an introduction to Elamba. Dingboku is the older dance, and as far as I understand it existed before Elamba became current. But now they're sort of fused, with one as the introduction. And Dingboku songs are somewhat simpler than other BaAka dance songs. They usually just have two parts, interlocking parts. Sometimes it's even just a call and response. In the case of “Ame Ote,” it's a call and response. The call is “Eeya Ame Ote o-o.” And the answer is “Ame ote!” Everyone answers. And then it goes into little chant. And as I was learning these songs, I would ask people to explain it to me. Some of them were obvious if they had a few words. And some of them just had Ee Ya Ee Ya sounds. But this one I didn't understand. It's saying “Ee Ya not me, Oh. Ee Ya not me.” I thought, "Why?" So I approached Djakandja, the same woman who was highly pregnant at the time (who had refused to cook). And she was a bit of a timid woman, but she happened to be sitting there, and she was a very gentle, nice person. And I felt comfortable asking her, "So, what does this mean?” She explained to me that the story behind the song was that a young woman goes into the forest and doesn't come back for a while, and her parents say, "Oh, you have been fooling around with some man in the forest.” And she is saying, "Not me. Oh. Uh uh, not me.” So that's what the song is about, sort of coquettishly saying, "Not me, not me." And this sort of ambiguous as to whether she really was or not. Justin helped me translate that, to understand that.

B.E.: You witnessed the early stages of evangelical missionary work among a group of BaAka. Briefly describe the initial drama you saw with the arrival of the Grace Brethren Church some 20 years ago. And then, if you can, bring us up to date on what's going on with missionary activity in this area more recently.

M.K.: That is a big question. I will try to keep it short, and Justin will have some things to add. When I first got there, there really wasn't much of a buzz going on about the missionaries. But in my second year living in Elanga’s camp (Elanga was the elder), the presence of the Grace Brethren became more of an influence on BaAka life, and it became very divisive. And within that time when Justin and I took our trip overland to the Congo, we passed through an area called Dzanga. And Dzanga was a permanent camp, or little town, not really even a town, a forest village, where both BaAka and Bagandou lived, separated by a stream. And the Grace Brethren Missionaries had sort of set up camp at Dzanga, and had Bagandou eventually working for them, or with them. In one case, there was a very mercenary evangelist, somebody who would change his religion depending on where he thought a profit might be, as I observed over time. He was quite active in this particular moment, convincing BaAka that if they were to perform their own music and dance, they would go to hell basically.

I was totally shocked because I hadn't seen anything like this in the area that I had been living in. And people were explaining to me that they can't do their own music and dance because they will go to Satan. And the only dances they were allowed to do were these game dances. There is a dance called Elanda, which has some songs that go with it. But they weren't allowed to do anything that would reference ancestors or spirits or healing. And this was quite amazing to me. And shocking, and I actually started to argue about it to give a different point of view, because the assumption was that because of my white skin, that I was of the same point of view as the missionary. And I felt ethically obliged to express a different point of view, so that it wouldn't be assumed that I was of the same point of view. And in fact, some people assumed that I was the missionary, since there was this white woman named Barbara, or Bala Bala as she was called, who had been active in the Grace Brethren Church, and when they saw me, they would say, "Oh, it’s Bala Bala.” And I would say, "No, no. I am not Bala Bala.” And I got into an interesting discussion with one woman at Dzanga explaining that I didn't agree with the missionaries, and that I actually thought what she was telling them was wrong.

So then when we were back in my home camp with Elanga, some of these divisive discussions were creeping in to this area as well. And so after a while, I decided to speak up, and people were very, very interested in my different point of view. They were surprised and interested that I was not toeing the missionary line. And the people who were culturally the strongest like Sandimba and Elanga were the most responsive and interested in this alternative point of view. Everyone was, but they were re-articulating it for themselves as sort of an example of this alternative to what the missionaries were saying. And there was a point when we came back in 2000, Elanga’s family had moved to a different area, deep into the forest, but actually along the new logging road. And some new dances had come up, and what happened was the presence of the missionaries, and the missionary point of view ended up super demonizing BaAka practices. Elanga said, "Well, it might be satanic. If it's satanic, then I'm satanic. And we’re just going to do it." Because he wasn't about to give up his livelihood, basically the hunting efficacy and his identity, really, for the sake of this argument that it was Satanic.

But at the same time, there was something else going on. At Dzanga, that forest village where we first saw all of the missionary influence being so extreme, people were inventing a new dance that they called the "God Dance." And this dance integrated a bunch of different styles, their own BaAka style, the singing and dance style of neighboring group of pygmies, the Bolemba pygmies, who have had more of an integration with their neighbors, and then snippets from different kinds of Christian sects in the village, the songs and hymns from different sects, Catholic and Protestant. And also snippets of pop songs from the radio that they would've heard. So it was a whole conglomeration of styles that I began to understand as sort of an assertion of modernity, that they were able to sort of harness all this and re-articulate it in a way that made them current and hip in their own eyes.

So a few years later in this camp, Elanga’s camp, along the logging road and way in the forest, they were doing a lot of new versions of the God Dance. This was mostly the younger people. But they were doing this alongside new versions of hunting dances, and Njengi, which is one of the oldest and most widespread of BaAka dances that invokes forest spirits and ancestral spirits. It was still current, and there had been a new version of it being performed alongside the God Dance. But it was very controversial, because they were sort of self-demonizing at the same time as they were performing these things.

B.E.: So in the beginning when you were doing the initial work and you encountered the Grace Brethren Church, you reached a point where you felt you had to say something. This seemed like a force that could change, or over time, even eliminate the culture that you were studying. Christian belief seemed deeply opposed to that culture. Then later, when you returned, and you saw all these new hunting dances, the revived spirit dance Njengi, and also the God Dance, you began to see that the BaAka had perhaps the stronger culture, because it could incorporate the missionaries message without losing itself. So I guess the question is, if we were to sort of extrapolate ahead, from all you know, do you think future generations will maintain that kind of elasticity? Or is there still a fear that over time, the old culture will in fact be destroyed?

M.K.: A lot depends on circumstances. One reason that BaAka were able to elaborate in their own way on the God Dance and let it exist side-by-side with their deeper styles of dance is that the missionaries pulled back. There were troubles in the country. There was the military rebellion. There were lots of things going on that made it more difficult for the missionaries to operate. So BaAka were therefore free to interpret and extrapolate what had been introduced by the missionaries, but in their own way. Were the missionaries able to be more present and dominant, I'm not sure that would've happened, or not among the same people. There was more difference, for example, at Dzanga, where there are many non-BaAka Central African evangelists constantly looking over them, versus in other areas where there wasn't that kind of presence, and the BaAka were on their own to extrapolate for themselves.

So I think a lot depends on the circumstances, the particular area, and also the economic situation of particular BaAka. In places where the hunting is getting very difficult, either because the area is being hunted out by gun hunters, or because of logging, or farming nearby, then people are more vulnerable to others coming in and saying, "Well, you really need to live differently in order to survive." Where hunting is still plentiful, they are not as vulnerable to those kinds of things. But I think Justin can add to this. At his home, where he established his own coffee farm, there are now two main missionary centers that have made a home for themselves. One is Grace Brethren, and one is Catholic. So the Catholics who have been long-standing in the CAR—they were in CAR first, since the 1920s. Justin, tell us what's going on there.

J.M.: The problem with foreign missionaries is that, first, they are often ignorant. Instead of trying to look at people as they are, to learn and see things as they are, they want to see them the way they want them to be. Most of the time, they impose their thinking in a very destructive way. They want pygmies to stop dancing, to stop traditional healing, telling them that these are diabolical practices. They will tell them not to be themselves anymore, but without telling them the next step to take instead. But I think pygmies are very, very wise. They're very polite. You can tell a MoAka, "Do this," and he will say, "Yes, I will do this. I will come tomorrow morning." But then he won’t do it if he does not want to. It's the way they survive. They have been so many generations next to others. I consider pygmies like the last power in Africa right now, but missionaries are trying to weaken them, the same way they did to our ancestors. It's the same thing going on and on. I think many of them understand. They can sing when the pastor is there. The lady will come with clothes, shoes, they will get it. They will sing. But when she leaves, they come back to their usual life. So it's like a game. They understand what is going on, because they have seen enough, so they're very aware of this influence.

M.K.: Yes, but I would just have to say the other side of that, though, is to see other pygmies, not BaAka, for the most part, but Bolemba who in fact have lost a lot of their culture. So they may be resilient, but only up to a point where the resilience falters. So it depends on the circumstances.

B.E.: So if we look at the big picture, we could say that for millennia, these people have been able to keep their culture, despite incursions by Europeans, Arabs, the slave trade, all these things. Justin, when you say they are the last power in Africa, you are saying that they're one of the very last people who have really been able to hold on to the core of their traditional belief system, their art, their lifestyle. But ultimately, now, the forces of modernity are really starting to have an effect. On the one hand, you have the missionaries, but also you have the disappearance of the forest itself. I saw recently that V. S. Naipaul has a new book about Africa, and it notes that the Chinese are now coming in with machinery that is allowing them to destroy forest at a rate far beyond what anyone had previously managed. There has been logging for ages, but it has never impacted upon the expanse of the rainforest to the degree the Chinese are doing now. So with all these forces, is it fair to say that the forest peoples lives really are at risk, facing a threat unlike anything that they have faced through all this history that we've talked about?

M.K.: Yes, absolutely. Just like the rain forests are on the cusp of being destroyed, so are the lives of the BaAka. And even if you just look at neighboring Cameroon, and how the Baka—they are related, though not the same people—how the Baka of Cameroon are living for the most part in a much degraded, second-class citizen way. That could easily happen to BaAka in CAR as well, as the forest recedes, and as attitudes of their neighbors take hold. This is also true of Mbati pygmies near the town of Mbaiki (north of Bagandou).

J.M.: I think we are now trying to help allow BaAka to live the way they want to. Even though the forest is getting poor, and some are forced to live in permanent camps, but we are going to teach them to learn, to adapt, to farm. Because living in the same place for long periods requires different technology. So we are willing. We are a team that is willing to help these pygmies, so they can remain themselves. We don't want them to lose their identity, to lose their power. That's what we are trying to do right now. I think in the Bagandou area, in the Lobaye area, we are hoping to protect them in this sense.