Twenty-five years ago, Grateful Dead drummer, “Rhythm Devil,” and autonomous ethnomusicologist (unofficial, like myself) Mickey Hart assembled a dream team of global percussionists. They were all artists he had known and worked with, but they had never played together. The team was Zakir Hussain and Vikku Vinayakram from India, Babatunde Olatunji and Sikiru Adepoju from Nigeria, Airto Moreira and Flora Purim from Brazil and Giovanni Hidalgo from Puerto Rico. They all went into Studio X in Sonoma County, California, and began to improvise. There were no rehearsals and no compositions to rely upon. Players took turns starting things and everyone else listened and joined in as part of a collective search for spontaneous, rhythmic music—as beautiful as they could make it.

The result was Planet Drum, a set of 13 spacious, multirhythmic jams covering a vast sonic range, and the first album to win a Grammy Award in the then-brand new category called “World Music.” (See Hart’s reaction to that news below.)

To mark the anniversary, Universal Music has now released a commemorative edition of the album, on vinyl and CD, with three previously unreleased tracks added. (“Throat Games” is particularly intriguing, a jolly crush of rhythmic voices!) Listening back is to enter the imaginative space of a freewheeling musical encounter between some of the world’s most accomplished percussionists. What is amazing is the openness of the sound, the way these monster players hold back from riffing and grandstanding, and create together, listening and responding, creating melodies as well as grooves.

There are polyrhythms, vocal hooks, gongs and bells, vocal collages, electronic sounds, and grooves suggesting Caribbean, Brazilian, African and Indian settings, while never quite settling into any culturally specific set of conventions. It’s a remarkable achievement and a far more pleasant listen than you might imagine from such a summit of players. They never clash, compete or cross swords. But nor do they hold back. It is a landmark moment, worthy of the re-release. So I gave Mickey Hart a call to look back.

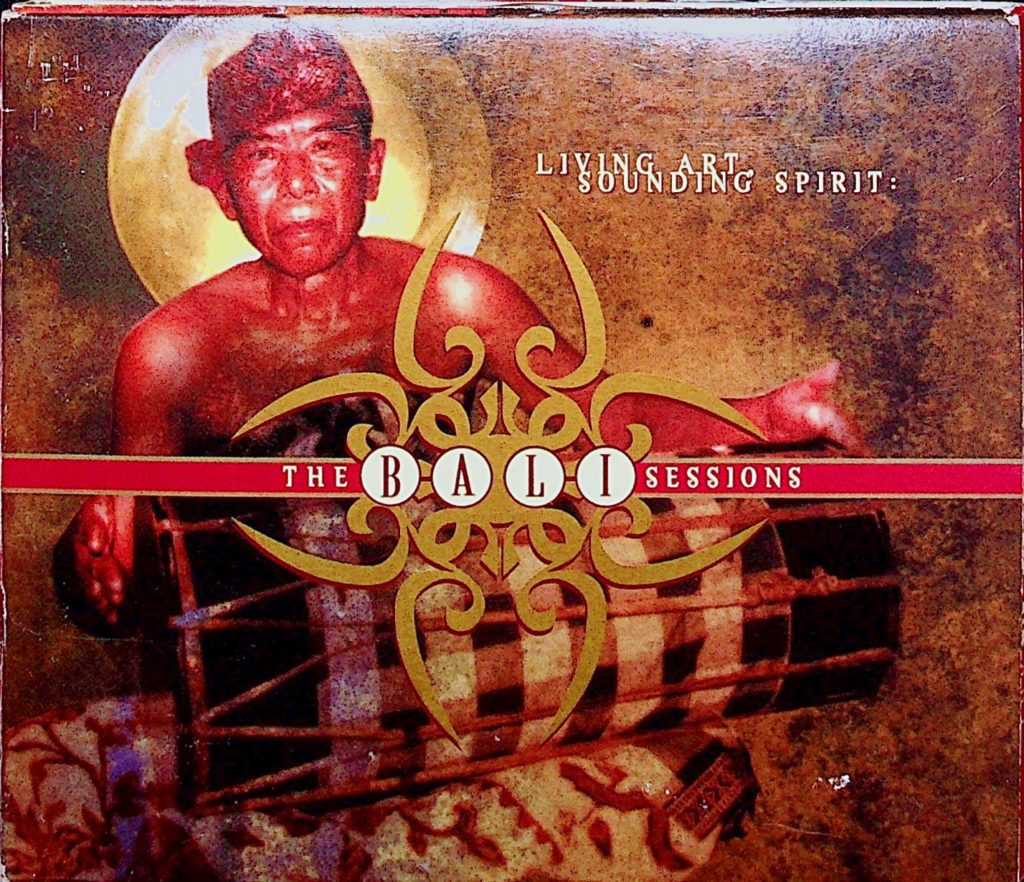

We began by talking about Indonesia, specifically Bali, a country I recently visited, and a place where Hart did important recording work in the 1990s, perhaps most memorably on the 1999 three-CD set of rare gamelan music he made for Smithsonian, The Bali Sessions: Living Art, Sounding Spirit. Here’s our conversation.

Mickey Hart: Where are you?

Banning Eyre: In Connecticut. But just back from one of your favorite places, Bali.

Really? What were you doing there?

I had been on a ship giving lectures about Indonesian music, and the trip ended in Bali. I saw a great kecac dance in Ubud—you know, the monkey chant with flying fireballs and all that. Terrific stuff.

Have you listened to the kecac I recorded on the Bali Sessions CD set?

Of course. In fact, I featured that release in my lecture on Bali music. That is a fine piece of work.

So you are back in the United States now.

Yes, until January. Then we go to Nigeria. Never a dull moment.

Wow. Something that you might want to take mind of is that Nigeria, of course, is where the talking drum comes from. That's really a good subject and there is a great historical record. You should read this book by John Carrington, Talking Drums of Africa. It's a bit out of date, but great. It gets to the historical record on where talking drums came from, how they were used, and how they became a transmission system.

[Editor’s note: I did find this 1949 book on Amazon. Just one copy available. The price: $2,030.91.]

They used to use the drums to transfer information. A lot of it was mumbo-jumbo, because the codes were always getting mixed up. There are some funny stories behind that. The book is dated, but I don't know any other one that's come up about the talking drums. It's an interesting subject.

It is. You know, we did a radio program last year that touched on this topic, Ancient Text Messages: Bata Drums in a Changing World. It was based on a book by Amanda Villepastour. But hey, let's talk about Planet Drum.

Oh yeah. I forgot about Planet Drum.

Well, it's been a few years, 25 to be exact. Obviously this is a classic ground-breaking record. I'm curious about the process you went through in the studio. I assume that these were played as much longer pieces that were then edited down to the shorter tracks we find on the CD. None of these tracks even breaks six minutes.

You are right about that. Well, it was like any other editing process. You just play on a theme. You play for as long as you want, as long as it takes to get the groove hard. And then you sit down and listen to what it sounded like. Most of these are first takes on this record. Then you just start clipping. Chop chop! You know, in a certain way. Then you put the vocals on. That's the way I've always operated. I don't usually do a three or five minute song. We play for long periods of time, and then you find the song. And once the song is found, you take the piece of it that is most succulent, that is the essence of what it could be. And remember, that was analog. Remember analog tape?

I do indeed. We still have a lot of it laying around.

Me too! And so then around that, the voices come together. And if the voices aren't good, you just overdub, touch them up in places. So it's just like any other recording of that ilk.

It's interesting listening to this with knowledge of a number of these players individually in their own idioms. I am curious about what it was like in the studio. It feels like a very friendly, easygoing session. You can catch the vibe that everyone is really getting along nicely, and getting off on each others’ stuff. But I'm wondering if there were any challenges in the studio with people coming from such different backgrounds. Did any of the concepts have to be massaged in order to sit next to each other comfortably? What were the group dynamics like?

Well, this was a special one, of course. There was absolutely no worry in my mind that this would work, and that we wouldn't have to compromise anybody's sensibility. Because I knew them all. I was the only one that knew everyone. Some of the group knew maybe one or two of the other members at that time, or knew of them. But they had never played together. These were handpicked. I knew the sensibilities and the personalities of each one of them. And they were just so positive. In my interactions with each one of them I thought, "Wow, throwing them together in a big pot, and just lighting the flame that would bring it all together. And it did."

In that respect, emotionally, it worked. It was challenging. But everyone was trying to bring each other into a new groove, and they were sharing in the best possible way, as music should be. No competition—just trying to make music for music's sake. The only thing was the disparity between the sound levels of the instruments. Some of them are louder than others. And so you had to have that sensibility of being able to play within your range. You cannot overplay. Just relax and have a good time in the groove. Those were really the only directives. Usually, for each one of those pieces one person would start. Another person would pick up on it, and another, and another. There were no rehearsals.

It was organic.

Right. No rehearsals. So we just got good sound and made sure the sound was right, prepared the table. And that was it. And we had Tom Flye as the engineer. A lot of credit goes to him. He has extraordinary ears. The rest of it was just magic. It rolled out the way it should, on the best possible sunny day. That's what this one was. A very sunny day!

It sounds like that. I remember seeing the group when you guys did a tour shortly after the album release, and the vibe was great on stage as well. I’m curious about how you feel listening to this back all these years later. Maybe you've been in touch with it, but for me I hadn't heard it in a long time. A couple things struck me. One is just the spaciousness of it. You got all these incredible percussionists, any one of whom could fill every single possible space, but they're not doing that. They're really listening to each other, and there's a lot of open space in it. Nobody is showing off. Nobody is grandstanding with all the hot stuff that they might do in other contexts. It’s very musical. It feels like pop music in a way. But I wonder what strikes you listening to it back after all these years?

Well, it's pristine. It's just crystal clear now. The spaciousness is a big part of it. You hit that right on the head. Everybody was respectful, really listening to each other, and smiling. And that's what you get. It's nonaggressive. I think of it is more like romancing the groove as opposed to beating the drum, as it were. It's a personal way of playing the drum, like you'd play it when you are alone. You know, when I sit alone, I don't bash. I don't break my hands to make the sounds or anything. I just enjoy it. And that's what this was. It was a very enjoyable experience. No one was trying to break any speed limits. It wasn't about that. Listening was the big part of it, respect for each others' traditions. Because they knew each other by reputation mostly. And if you knew you were in the room with any one of them, who could just play and take it away, and make a solo record all by themselves.

Exactly. They resist that urge admirably.

This is why I put them together. Because they had real respect for each other. You don't do that when you respect someone. In our brotherhood of rhythm, some people compete. They try to outplay each other. This was completely the other side. So I fostered that atmosphere. The sound was so good that everybody was really appreciating their instruments. They had never heard their instruments sound quite so beautifully coming out of the speakers. So they played with great care. It wasn't frivolous. It wasn't, “Yahoo, jam, jam, jam.” Everybody was trying to make something of great worth. We all knew that it was special. We didn’t know what was going to happen with it. We didn't even know about "world music." Back then there was no such thing. In fact, there still isn't.

I hear you. That was early days. A lot of water under the bridge since this album…

People didn't know what to do with so much of what I was doing then, the Tibetan monks… There was no place for all this stuff. Around the world, as you know, things were starting to pop up. Fusions. Most of them didn't work. Some of them did. And I know that the Grammys needed a category for Planet Drum. So they made a thing called World Music.

This was the first record to win that category.

Right. First world music Grammy. After we won, I called them up and said, “Hey, cool. Thanks for this world music Grammy. But, you know, there is really no such thing as world music."

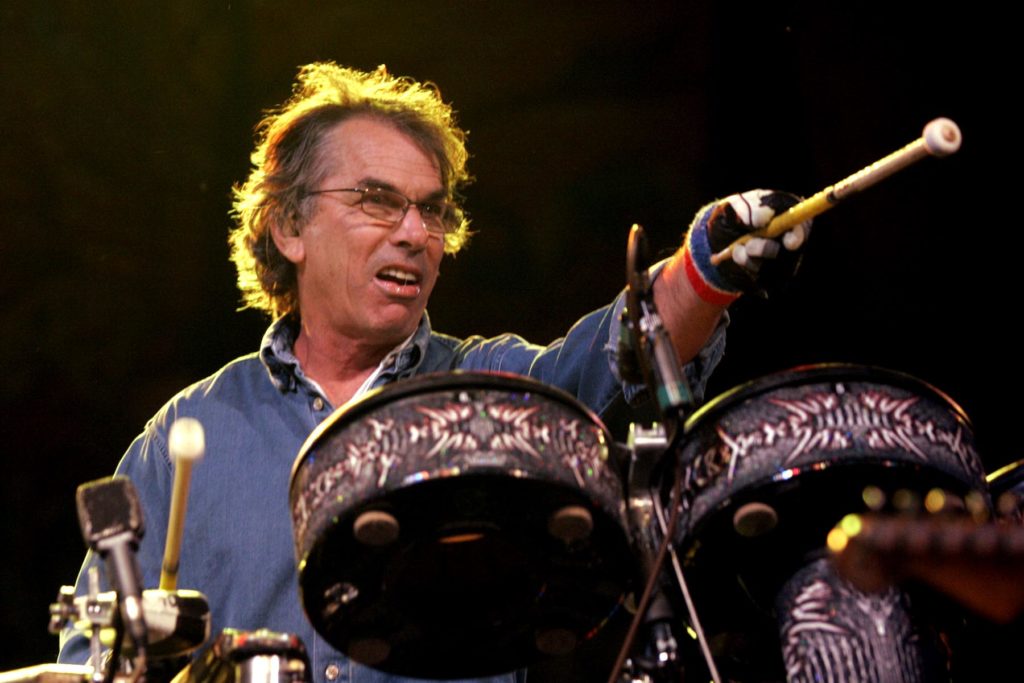

Mickey Hart performs during the Harmony Festival, Fri., June 6, 2008 at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds.

Mickey Hart performs during the Harmony Festival, Fri., June 6, 2008 at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds.

Later on, they divided it into two categories, traditional and contemporary, a slight improvement. I don't think they still quite know what to do with this kind of music, to this day.

I know. It was a stab at doing it. Trying to find something that was outside the Western sphere. But now, it's gone way beyond. To me, it is the world's music. It's always been the world's music. It all depends where you are. That determines whether it's world music or indigenous music. If you're in the Philippines, Adirondacks music is world music.

I always liked Ben Mandelson’s definition: “Local music, not from here.”

Who said that?

I believe it was Ben Mandelson, formerly of GlobeStyle records in the U.K.

I thought you said Mantle Hood. By the way, if you want to read a great book about gamelan music, Music of the Roaring Sea by Mantle Hood. That's the definitive one. He's from the first wave of ethnos, and actually Fred Lieberman's teacher, a teacher to many. [Fred was Mickey’s co-author on the book Planet Drum.] Hood is definitely a great read for anyone who's thinking archipelago. Java, Bali, any of those gamelan places.

That sounds like a must for me. I really got a taste for that part of the world after this recent visit.

You went to Denpasar [the capital of Bali]? Man, I've got a lot of great stories about Denpasar... But go ahead. Planet Drum.

Right. If I'm not mistaken everybody involved with this project is still around, except for Baba Olatunji.

Correct.

So, any chance of getting the band back together for a reunion tour?

I don't think so. I think we did that. Now, I'm looking to the future. I don't look back very much musically. Zakir and I are making a record right now. We've been working on it for a couple of months now. I brought Sikiru in on a little of it, but as far as getting the band back together, I don't think so.

O.K. Let's talk about the cultural environment and how it has or hasn’t changed for this sort of project. A lot has happened in 25 years, but do you see this as a better environment or a more difficult one?

You mean for the people who are making the music?

Well, of course everybody's having a hard time making money with the changes in the recording industry. But I'm thinking more about the audience, people's openness to the sort of project.

The thing about Planet Drum was that it was processed percussion. It was melodic. It had melody. It had harmony. Just being a drum group is very hard to hear unless you are really into rhythm. Most people aren't into rhythm in that kind of pure context. They’re into rhythm in the context of other music. If you listen to music now, it's mostly rhythmically driven. But these kinds of projects fall between the cracks. So if you don't go after this kind of music, it won't exist. There's hardly any promotion behind these kinds of projects. I was just lucky because I had Rykodisc and Don Rose and Arthur Mann.

Yes. That was a moment.

That was a moment. Most of these companies were not really interested in world music. So it was difficult for someone who was creating a life in rhythm, you know, using rhythm as the basis of all their musical compositions. It's still difficult. At that time, I was trying to make a 20th-century gamelan. That was always the idea.

Gamelan again. I think I recall you describing one of your earlier bands that way, the Diga Rhythm Band. Right?

Yeah. Diga Rhythm Band. The idea was gamelan. Tuned percussion. There was variable pitched percussion and various things you could play that you would not normally get in the West. It was very familiar to me and everybody who was in that group. We all loved that stuff with a passion. It was a passion project. It's hard to be just a rhythmist in the sense of creating a new music. Being a rhythmist in another form that's popular is one thing, but to be able to strike out like a Planet Drum and create a new genre–you know, you can't do that every day.

Indeed not.

It was like a gift from the gods. The rhythm gods. Very difficult. Nowadays, of course, everybody knows what a djembe is. Back then, few people had even seen a djembe.

People sure know what a djembe is now. They’re everywhere. Even in Bali. I saw drummers playing them on the beach.

Back then, all people knew was shakers and clave sticks and timbales. That was about it. So there was a uniqueness as well. There was an intrigue for people who haven't seen these instruments. When we toured, they would come up to the stage before the show and just stare at the instruments. Just stare at the empty stage, just with the instruments before we played. I couldn't believe it. They liked seeing the instruments as much as hearing them.

You mentioned the new record your working on with Zakir. What else have you got on the horizon?

Oh, I've got a lot of stuff, Banning. Installations. Planetarium shows. All kinds of stuff. As a matter of fact, right now I'm working with Steven Feld, who you probably know from Voices of the Rainforest.

Yes, I recently came across that release when I was surveying my Indonesian collection. And I’ve read his book about Ghana as well.

Right now he's doing a 7.1 mix of his rainforest recordings. I've got the original tapes. There are some beautiful pieces. We’re working at Skywalker. We’ll be mixing it there next week. So there's a lot of these kind of multichannel natural environmental things that are very interesting. Of course I'm working with the cosmos. I'm working with stem cells. I'm working with brainwave functions, so I've been sonifying all these things on a grand scale. They're coming together on another project. I have a lot of projects that will pop out next year. Some of them I can't discuss with you, because, you know, contractually…

Got it. We will stay tuned.

Some of these are fantastic, the most fantastic things I've ever done in my life. I’ll let you know when the time comes. Hey, I gotta go. They're pulling me out of here.

Great to talk. Thanks for the time, Mickey.