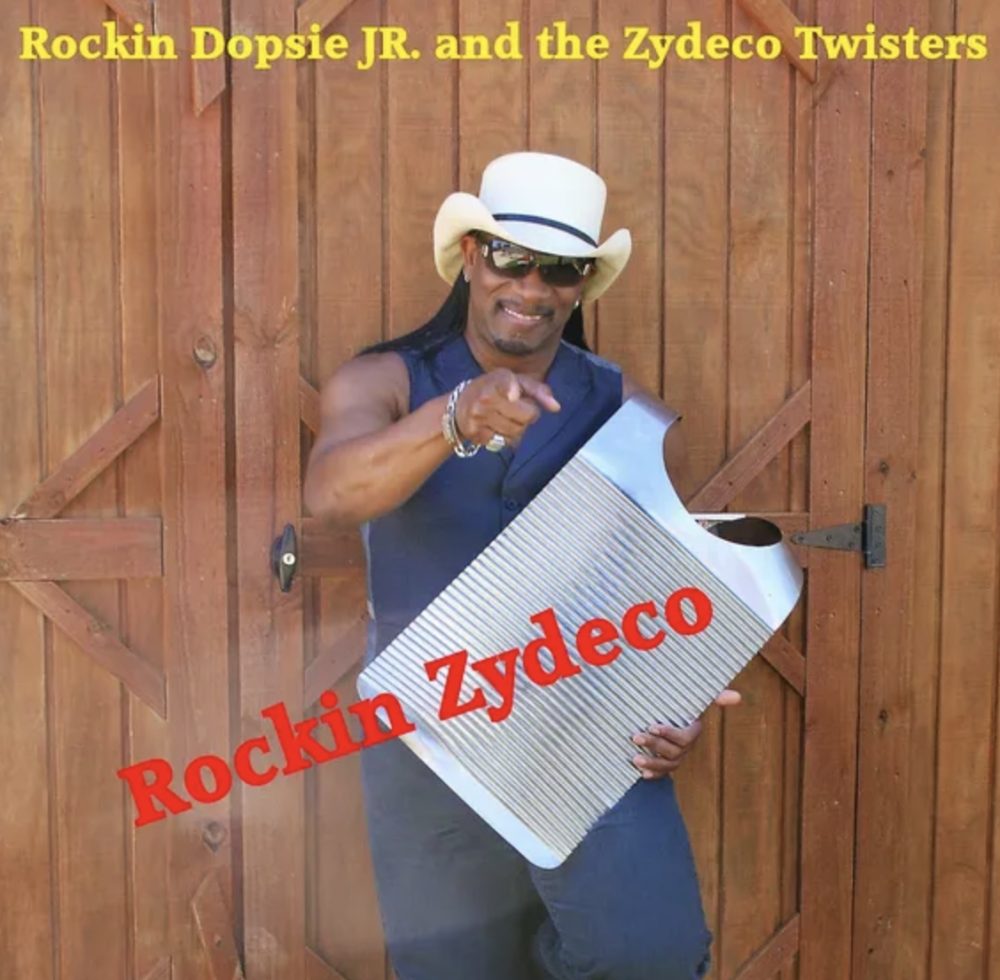

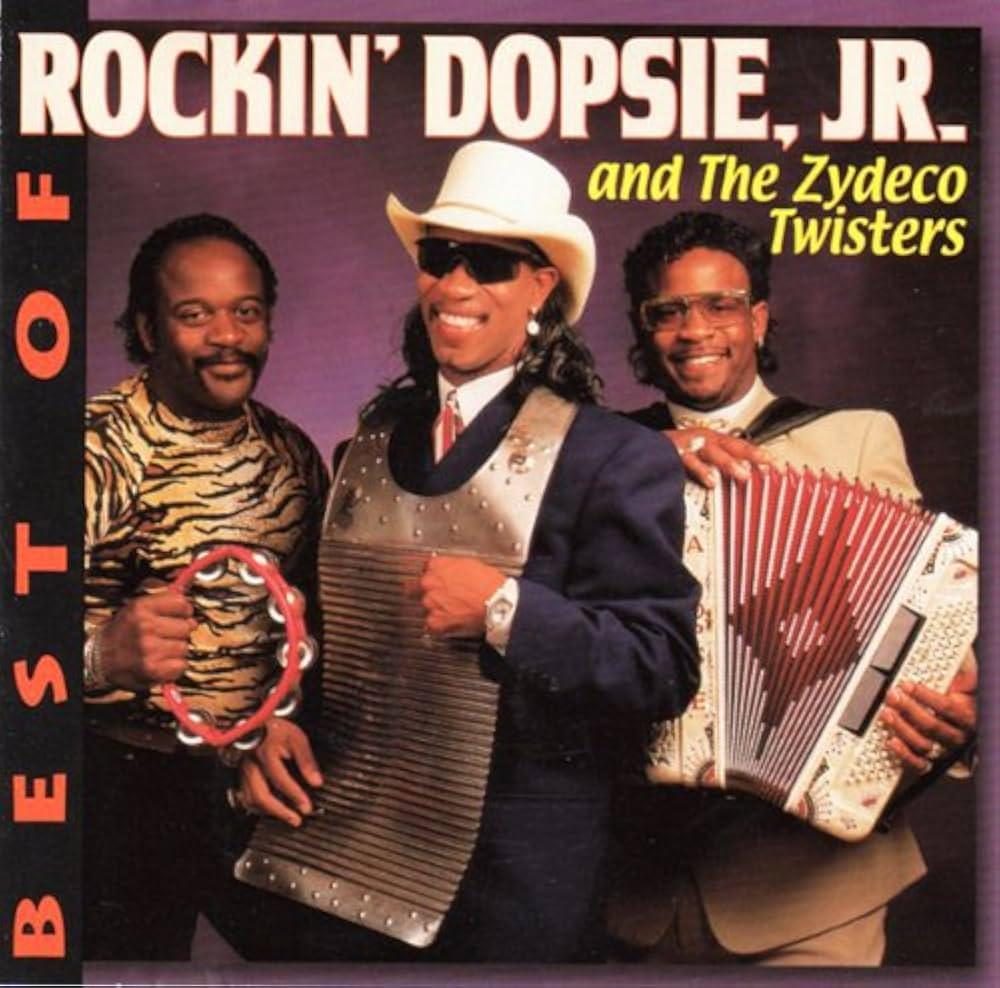

Rockin’ Dopsie Jr. (born David Rubin) is the son of Zydeco legend, accordionist, singer, composer and bandleader Rockin’ Dopsie, who died in 1993 after a spectacular career in music. Dopsie Jr. eventually took the helm of his father’s band, The Twisters, now called the Zydeco Twisters, and he’s just out with a new album, More Fun With Rockin’ Dopsie Jr. and the Zydeco Twisters (ATO Records). It’s a punchy blend of Zydeco, blues and, appropriately, rockin’ grooves. Afropop’s Banning Eyre recently spoke with Dopsie Jr. about his career and the new album. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Dopsie, how are you?

Dopsie Jr: I'm doing great. How are you doing today?

Excellent. So glad you were able to do this. I don't know if you're familiar with us, but we've been a radio show around the country since 1988, digging into all different kinds of musics related to Africa, wherever they may be found. And that certainly includes Zydeco.

There you go.

Myself, I'm no expert on Zydeco. I could tell you more about Congolese music. But I do love Zydeco. I once saw your dad many years ago, and of course, he was awesome. But tell me a little bit about how you came take over his band when he passed?

Actually, growing up as a kid, my grandfather was a Zydeco accordion player. And my father played after his father, but my father was left-handed. So he took a right-hand accordion and turned it backwards and played it upside down. I don't know if a lot of people really caught on to that.

And I remember growing up, my father, when he'd get off of work, he'd come out and rehearse his band, until he became internationally known. Then he started traveling. And I remember the late great Clifton Chenier would come over to my father's house and they’d play out on the back porch and they have their little drinks and stuff. And my oldest brother, Alton Junior, who we call Tiger, he started performing with my father in 1976. I started playing with my father right after I graduated high school in 1980.

My father had his cousin, Chester Zeno, they called him Shorty. And he played washboard, but he played with just his left hand. And he’d pick up a wooden table with his free hand, and you know how heavy those oak tables was. He picked up an oak table and he'd hold it in the air while playing the washboard. And he'd do the same thing with a chair. So that was his gimmick. And people would come to see that. It was something very amazing to see.

Then as they got older, he had diabetes and he had to have his legs amputated. So my father said to me, “Well, you have to step up and take Shorty’s place.” My father knew I could dance. My thing was I loved Zydeco music, but I also loved the old entertainers like James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Michael Jackson, Sammy Davis Junior, Prince... I was into all the entertainers. So my father said, “Well, you're going to have to come up with a gimmick.” And I was like, well, I know I can't pick up a table and a chair. So I'll dance for you. That's when I created the cowboy hat, the sunglasses. I had the toothpick, cowboy boots and an apron. And that's pretty much when Rockin’ Dopsie Jr. was born.

That was in 1980?

1980. Right out of high school.

So how did you end up taking over the band?

I was my father's showman and I opened up the show \with three or four songs a night before he came on stage. Then while he'd play accordion and sing, I'd dance and keep the crowd riled up and stuff. When my father passed in 1993 he had a show in San Diego street scene. And I'll never forget his late manager, Ellis Palette, and I'm sure you're familiar with Quint Davis of Jazz Fest [The New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival]. It was Quint Davis who told me, “You are now Rockin' Dopsie.” He's like, “You have to be Rockin' Dopsie. You have to go out there and make your father proud. Just do what you do, man. Just be you. The people already love your energy. They love your spirit. Just keep that energy up for your father.”

We went up and we did the gig and it was supposed to be my father. He was on the bill along with Zachary Richard and the late Gatemouth Brown. Me and Gate was real close. And he and my father was real close. Gate was like, “Man, get out there. You're already crazy. So go out there and jump up, do your splits, get wild and do what you got to do.”

I took his advice and the show went great. The crowd loved it. My little brother Anthony was 18 years old at the time. And we were trying to figure out which accordion player we was gonna put in my father's place. But all of them, like my cousin Buckwheat, he already had his band. Then my other cousin, Major Handy, we thought about him, but I really wanted to give my brother Anthony a chance because my father let Anthony play washboard around the house and Anthony played a little accordion.

But my father taught Dwayne more accordion than he taught Anthony. At the time, Dwayne was only 13 years old and he was still in school. And my mama wouldn't let him travel. So we took Anthony. It was Anthony’s first gig playing in front of a live audience and he did well.

And when the show was over, you know, Gatemouth was like, “Man, I knew you could do it. And I'm proud of you.” And further on down the line as things went, you know, the late great BB King and Aaron Neville and the late Dr. John, they were like, “Man, we knew you could do it.” And it's not that I thought I was Rockin’ Dopsie. I couldn't fill his shoes because there was a lot of shoe to fill! I had to create my own image, my own style. And here we are today, you know.

Well, I think you're doing a great job. So after that first gig, you thought, “Yeah, I can do this.”

Actually, after that first gig, I was ready to jump on stage with Zachary [Richard], because my momentum was up. I was ready for the next gigs, and I just kept popping them out. The more I did it, the better I got. I thought I was always, you know, if not the best, one of the best washboard players other than, you know, Clifton Chenier. I remember playing with my father at the Maple Leaf on Oak Street in New Orleans and Bono from the band U2 came in. My father had no idea who Bono was. And I remember speaking to him and he was like, “Man, does that thing play you or you play it? And in Bono’s autobiography, if you read it, he had a write-up about us playing at the Maple Leaf that night. He called me the Jimi Hendrix of the washboard. So that was pretty hip.

You’ll take it.

Most definitely, man. And I guess I did well because further on down the line I've done recording with all sorts of people. I did the Paul Simon thing with my father. But then we recorded with Bob Dylan with my father. Then I wind up recording with John Fogarty, Jimmy Buffett, and a whole lot of greats with the rhythm of the washboard.

So I knew I could play the washboard. But my whole thing was keeping the Zydeco sound. I played a lot of songs that I played onstage with my father. God gave me 25 years with my father, traveling on the road with him. So I played all the songs my father played like “I Got a Woman in Josephine,” “She's My Little Girl,” “Let the Good Time Roll.” I played those in my set for like two years. And then, like I said, I always was into the rock and roll and stuff. So I kind of took music from a lot of other musicians and kind of put a little Zydeco twist in it. I took the song “Long Train Running” from the Doobie Brothers and did my own twist on it. I didn't want to get away from that Zydeco sound because, if you listen to Zydeco and country music, you know the chords is one, four, five. I didn't want to get away from that. So that's pretty much where I'm at today.

Beautiful, man. Let’s talk about this album. I'm not familiar with your discography. How many albums have you done on your own?

This is number 15. But I have to say, other than the first record I did on AIM Records for Peter Noble out of Australia—that was the first record I did after my father died, it was 1995, a record called Feet Don't Feel Me Now, and that was one of my best records until this one came out. Man, I tell you, with Randy and Stewart producing [Randall Powter and Stewart Lerman], I'm in awe of the way it came out. I just love it. I first met Randy when we did a couple of songs for the soundtrack for the movie “Roadhouse.” We were in the studio in New Orleans, and Randy said, “Man, you have a great voice.” And I'm like, “Oh, come on, man.” He goes, “No, man, I love the way your voice sound. I'd like to do a record on it.” And I'm like, “Okay, let's do it.” And we did it, and here we are. And I'm glad we did because I got a chance to do a lot of songs I love playing, that I've played in the past and I'm playing now, you know, and I got a chance to get my little brother, Dwayne, on the record with me, in fact all four brothers. Dwayne was so happy with the way the record sounded. He went and recorded his own record and got me and the brothers to play a couple of songs on it, and it sounded great as well.

Let's talk about some of these songs, starting with your cover of Paul Simon’s “That Was Your Mother.” What do you remember about the original Graceland session when your dad played accordion on the track?

Well, actually, I got a funny story about that. You ready for this? We were playing in New York City at Tramps. We were opening up for Dr. John. And the late Ed Bradley, the late Jimmy Buffett, and Cyndy Lauper were there, and Cyndy brought in Paul Simon. She was a big fan of my father. She bought him some flowers and roses or something. Now my father had no idea who Paul Simon was. I had to explain to him who Paul Simon was, Simon and Garfunkel and all that.

Really?

Man, but you have to understand my father grew up in Carencro, Louisiana. Hardly spoke English. My parents, my grandparents, all they spoke was French. And the only things my father ever listened to was T Bone Walker, B .B. King, Bobby Bland, Muddy Waters, you know, Howlin’ Wolf, all the old blues. He never knew Paul Simon. He wasn't into that diverse of music like I was growing up. So Paul Simon told him, he said, “Look, I'm doing this record, Graceland. I'd like you to be a part of it.” And my father said, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. Thank you. So Paul told him who was on the record. Then we went back to Lafayette and played at this place called Grand Street. And my dad asked this white guy, Mike Hennessy, he goes, “I met this guy Paul Simon…” And Mike goes, “Dopsie, you want to do this record. You want to do this record.”

So my dad said, “Okay. I never heard of the man.” So Paul Simon came. We went to Crowley, Louisiana, about 20 minutes south of Lafayette, at J .D. Miller Studio. And what it was… He had Buckwheat play three instrumental songs. And I think he had Terrance Simien play three instrumental songs. And he had my father play three instrumental songs. We all were in the studio at different times. But one of the songs my dad played was “My Baby She's Gone.” So Paul Simon took the music to that. [singing] “Well, a long time ago, yeah, before you were born. Well, I'm standing on the corner of Lafayette...”And that's how Graceland came through, and Graceland won Grammys, won best record, record of the year. My dad got a gold platinum record Grammy from Paul Simon.

But this is the fun part. This is the story. Paul Simon called my father and said, “Look, they want us to play the song on Saturday Night Live.” And my father was like, “Ah, okay, that's fine. What's the date?” So Paul Simon gave him the date. And mind you, my daddy was an old Catholic boy and he believed the church and everything. So he told Paul Simon, he said, “Can you change the date?” And Paul Simon said, “No, I don't think they can change the dates. Is there a problem?” And my father said, “Yeah, I promised the priest at St. Francis of Assisi in Houston that I was going to play at the church hall that night. He said he sold out already. So I can’t back out of it.”

Oh man, I was so hurt that we passed up Saturday Night Live! But you know, he was a man of his word. We missed that opportunity. But then a few other doors opened up for us. And I really think when we did Paul’s Graceland album, that opened a lot of doors for my father, because he was known for Zydeco music, going over to Europe for a long, long time, him and Clifton Chenier back in the back in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

That's a great story. Graceland, of course, was a big deal for us because it came out right when we were starting to pull together our radio show on African music, and it also opened a lot of doors for the African artists who were involved in that album, and others as well. It’s a landmark. I love your cover of “That Was Your Mother” on this new album. I also really love the slow songs on this album like “No Good Woman” and “I'm Coming Home.” Your vocals are just so strong on those tracks.

Thank you so much. I grew up listening to those songs. “No Good Woman” was written I think in the 1960s by the late Rockin’ Sidney. And growing up, my grandmother always listened to Clifton Chenier's music. I think that she was more into the Clifton Chenier sound than her own son, you know. I hate to say that. But I guess she just liked Clifton's sound. And I'll never forget when Clifton Chenier recorded “I'm Coming Home.” I was about 17, 18 years old and Clifton brought the album to my father for him to listen, and my father told him, “You got a hit there, that's a hit!” I kept playing that song over and over. It just touched the soul, and that “No Good Woman” had the same thing. I was always a fan of Rockin' Sidney as well. All I listened to as a kid was Zydeco musicians like Clifton, Buckwheat, Fernest Arceneaux , Boozoo Chavis, you know, John Delafose.

Tell me about the song “Dopsie’s Boogie.”

“Dopsie’s Boogie” was written by me and my father for the Santo record label. We were in the studio and Floyd Swallow, rest his soul, said to my father, “Let's do a boogie, Dopsie, you got a boogie?” And my daddy looked at me and he said, “Davis…” He couldn't say David; he called me Davis. He said, “Davis, you think we can find something under the hat?” I said, “Yeah, let's see what we got. And then it just came up.” [he sings] It was just the instrument and we wrote it just trying to stay on the one [chord] as long as we could ‘til the end of the record. And it turned out to be a smash because when we played it live for live audience, people would request it like two, three times in the night. And that just came up in the studio. We didn't rehearse it. I think it was for the Saturday Night Live Rockin’ Dopsie album.

Are any of these songs your originals?

No. All these songs are covered from other people, like the song “I Found a New Love.” That song was done way before I was born by my cousin Rosco Gordon. I wanted to put a big alto saxophone in it to give it that deep, deep sound, you know, and we tried it and it worked out well. That was something that Fats Domino did.

I remember growing up, Clifton wrote this song called “Ay, Ai Ai. “I was sitting down alone and along came a creole queen. A mockingbird took her by the hand. As she went strolling along. He said, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, aye, no more!” It just repeats itself, you know, and I'm like, I got to record this song. And then I had to record “Ma ‘Tit Fille,” which means “my little girl,” because Randy really liked it. But when it was recorded.. I'm going to say this without trying to put it in a racial way. But when it was originally recorded, it was “my negress,” my little nigga woman. That’s how my father recorded it. But when Buckwheat recorded it, they changed it to “Ma ‘Tit Fille.”

Wow.

And I always loved Barbara Linda Ozen’s “You’ll Lose a Good Thing.” I sang that on the track for the “Roadhouse” movie. My wife wanted me to sing it the way Freddie Fender did it, because he added verses to it, but I just wanted it the way Barbara Linda did it because it had that soul feel, you know. And then “I Can’t Lose With the Stuff I Use.” My father wrote that. [Sings] “There's a whole lot of people like to see me down. If I keep on trying, maybe I be rich someday…” You know, it just had that feel. I call that I call that the Rockin’ Dopsie way. I told my brothers in the studio, “Hey, man, let's do it the way we do it on stage. Let's do it the way dad would want us to do it.” And that's how we did it

Well, the album all feels completely organic. You can tell it was recorded with everybody playing together at the same time.

Definitely. Everything came from the heart.

It’s a rich blend of blues and rock and soul and Zydeco. It just meshes beautifully.

My thing when we went into the studio was like, I'm gonna cook a big old pot of gumbo and I'm gonna put in all the ingredients, sausage, tomato, onions, bell peppers, shrimp, okra, everything in there. And it really came out great. Not that I was surprised, but it came out better than expected is what I want to say. And for you to like it, I thank you. I really appreciate that.

It brought me back to my early days. I used to go to New Orleans, but I haven't been in way too long. I've got good friends that live there and I got to have to get back. You know, I was interested in you're talking about your father that he spoke French. I grew up in Canada, and I was always relly interested in the whole story about how the people from Acadia went to Louisianna and became the Cajuns. It's just an amazing piece of history. You say your dad and grandparents only spoke Cajun French?

My grandparents spoke French on both sides. My father was born and raised in Carencro, Louisiana, and my mother was born in Bow Bridge, Louisiana. My father had only a first-grade education. He couldn't read or write. If he saw his name on a piece of paper, he wouldn't recognize it because he had to help my grandmother break the crops and raise the family and stuff. And I remember this old lady—I went to school with her son—Ms. Zizé. She used to tell me this story. She said, “We used to be catching the school bus in the morning. and your daddy used to be playing his accordion under a tree, and we used to tell him, ‘You better come to school. You ain't gonna learn nothing.’ And he said, ‘Yeah, well, I might not learn nothing, but you're all going to pay to come see me play music one day.” That's a story I'll always remember.

I love it.

But yeah, my parents, they spoke French to one another. My mother spoke great English but when my parents would speak to one another or they'd speak to their parents, they'd speak French. That's how my brothers and sisters and I learned how to speak it. You say Cajun, but I say Creole French. They spoke Creole French.

I remember doing a show in Munich, Germany—I think it was like 1987, ’88-with Ray Charles. And my father sang Ray’s song “I Got a Woman in France.” [Sings lyrics in Creole French] The crowd was getting into, and Ray Charles, I guess he recognized the music. So when the show was over, he asked my father, he said, “Oh, country boy, let me ask you something. That song you played. What was that one of my songs?” And my daddy said, “Ray, I have to tell you, growing up, I was a fan of yours. So I had to play your song for you just to show you how much I appreciate what you did for me in my career.” And I'll never forget Ray Charles telling my father, “Well, I tell you what. I don't know what you were singing, but I like it.” I wish at that point I had a video camera so I could recall that I lived that every day of my life.

I bet you do. Say, where that name Dopsoie come from?

It came from my grandfather. My grandfather used to tap dance. He played accordion, but he'd rather tap dance. I think that's where my dancing came from, and he always wore a hat. I never met him. I was born a few years after he passed, but I was told he always wore a cowboy hat and boots. But the name Dopsie came from my grandfather because when he danced, they called him Lil' Dopsie. And my father always said, if ever I get a band and start playing music, I'm gonna call myself Good Rockin' Doopsie, and it happened.

You come from three generations. You've lived Zydeco history, man. That's a beautiful thing. So where do you feel like Zydeco is right now? Zydeco has this real core audience that just never goes away, but I think it kind of ebbs and flows in the mainstream. You tour a lot with your band. How do you think Zydeco is faring in the American music scene today?

I think where the state of Zydeco is at right now is a must-see and a must-hear. Because when I'm out on the road and we playing festivals and stuff, and they got two, three stages, and if it's me or another Zydeco band coming on, that's where the crowd's at, where the Zydeco stage is. A lot of people are getting hip to the Zydeco sound and loving it. A lot of people learning how to dance Zydeco. I don't know if you know this, but my little brother, this past Jazz Fest, was invited on stage to play with the Rolling Stones.

Really?

Yeah, he played accordion with the Stones at Jazz Fest. He told me, “I'm gonna get one on you.” ‘Cause me and him, we joke like that. I played Jazz Fest years ago when Simon and Garfunkel reunited. And then the last couple of years, John Fogarty played Jazz Fest and he got me to play. What an honor. What a legend! He just loved the sound of the Zydeco and the washboard. And when we played, he wanted to do “My Toot Toot” and he also wanted me to play on “Rolling on the River” [“Proud Mary”] and some of his songs, and the crowd loved it.

So when you have people like rock and roll legends, like the Stones and Fogarty, BB King, Buddy Guy, the late Jimmy Buffet, the Neville Brothers, Dr. John, the greats, you know… When they hit a sound on a washboard, it doesn't actually have to have the accordion because the keyboard player can put the accordion sound in it. The washboard is there to give it that Zydeco feel.

You’re right. That says a lot.

I was kind of disappointed, I think it was a year or so ago, when they did a tribute to Paul Simon. They had Irma Thomas on the show, and they had Trombone Shorty on the show, and they did a great job. And the only living member from the African band that played on Graceland was the bass player.

Yes. Bakithi Kumalo.

I've always wanted to meet these guys, but I never met none of them. And I wanted so bad for them to call me and have us play “That Was Your Mother.” I forgot who did the song. But when the guy came out and did the washboard solo, I was like, “No, no, man, that's not right!” But hey, it all sounded great. I just felt I should have been a part of it.

The washboard is one hell of an instrument. It's absolutely specific and the way you play is awesome. The way you sing is equally awesome. It's an honor to talk with you. I hope I'll catch you some time on the road.

Please, I would love to. I would love to hang out and meet you in person and sit down and just enjoy talking.

I hope we get to do that. You know, I especially admire a band that can survive through generations, like you and your brothers are doing. You know Ladysmith Black Mombazo who sang with Paul on Graceland? These days, almost none of the original guys are still there, but the group is still strong, going all over the world and playing. That’s the mark of a legendary act.

You know, my father always told me, because we were real close, he always told me, “If anything ever happens to me, Davis, just take care of your mama, and take care of Dwayne, but whatever you do, don't change my music, keep the sound of my music the way I did it, the way we play it.” I wasn't too honest with him on that. I kind of got away from it a little bit, because the time has changed, you know what I'm saying? But if you come to a Rockin’ Dospie Jr. show, when I'm doing things “Sweet Lucy,” “Always on My Mind,” “She's My Little Girl,” that's his sound. I still have his sound in the music. So I think he's proud of what I'm doing.

Thank you so much for speaking with me.

Thank you. God bless.