All pictures by the author.

Between a brief dancing gorilla attack and some truly incompetent attempts at Congolese percussion by us, the crowd, it was another perfect day at the Nuits d'Afrique Festival in Montreal. Although that evening when I sat down to chat with Mû Mbana, a very philosophical musician from Guinea-Bissau, and he explained his belief that live performance was now less about showcasing the performer's ability and more about what the performer and audience create together, I felt a little guilty that we never managed to clap in time.

It was July 20, my first full day at the Nuits d'Afrique Festival. In the early afternoon, people gathered in front of the TD-ICI stage where they were outfitted with a number of Brazilian drums and formed a little bateria under the guidance of Zuruba, a local samba school. They started with just a few “drum and response” exercises, and by the end, the group was thundering along capably.

Over at the corner of the festival, Elli Maboungou tried to teach us Congolese drumming. He explained that the tambours are called “mama and child,” in homage to the matriarchal culture they came from, and the Canadians politely cheered. We didn't know it, but that was the last time we would clap correctly until the session ended. God bless the patient Elli, but we just weren't getting it.

The heat of the day abated, shadows got longer and the Montrealers with 9-to-5s began showing up as the Resojets played laid-back ska-reggae fusion.

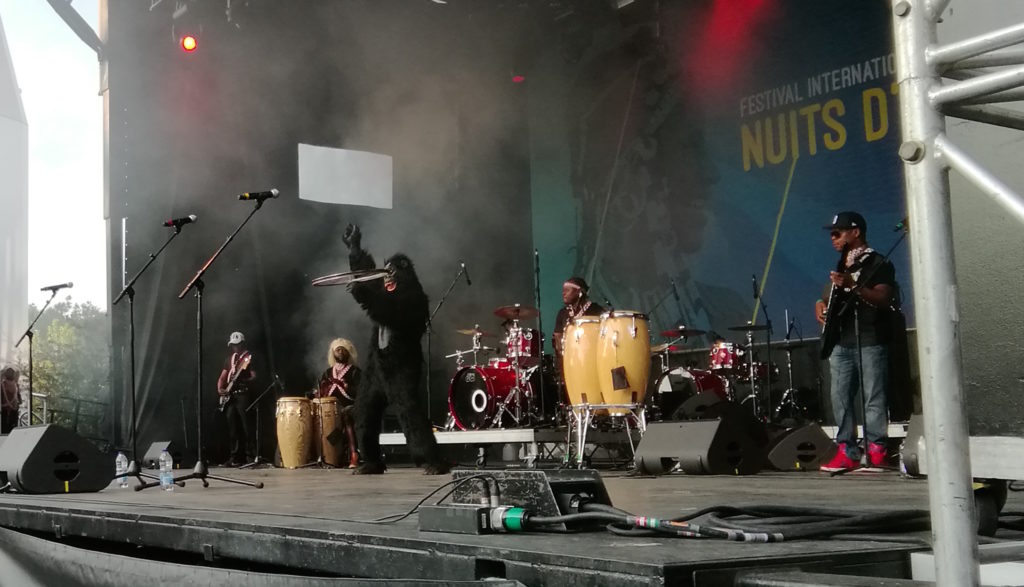

A brief technical snafu during Moto de Kapia. Photo: Ben Richmond

The local Congolese group Moto de Kapia followed with the fleet guitar work and (well-executed) rhythms characteristic of the country's music. The seven-piece band's colorful costumes stood out in contrast to the Resojets' rude-boy-goes-to-college look. They danced in wigs that reached all the way to their knees and fought off the stage-stealing antics of a very gifted gorilla dancer, who spun a bike wheel over his head.

The gorilla was dispatched by the dancers after a pretty stellar routine.

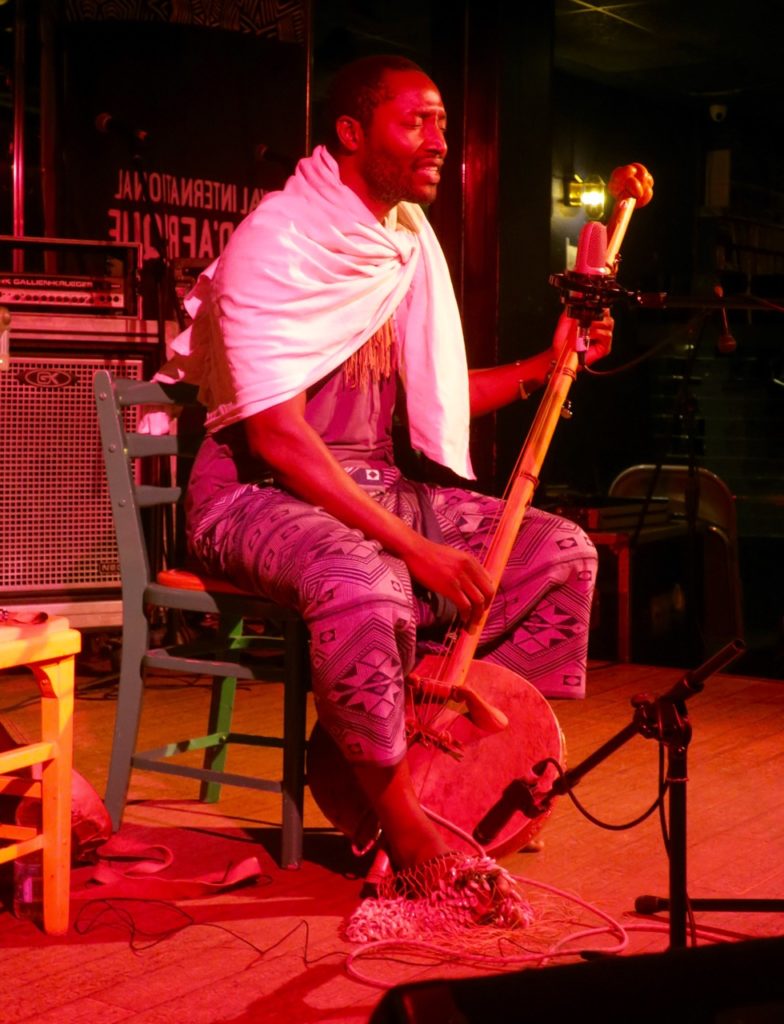

The festival was really cruising when I headed up the plateau to Club Balattou. I didn't want to miss Mû Mbana. He had come straight from the airport to the club to soundcheck and generously agreed to sit down to chat before his long, hushed set that held the room utterly transfixed. A very reflective man, he explained his mentality when approaching live performance, why he built his own instruments and where he finds strings for the bënsuni while on tour.

We were talking about Kafka when I took this. We're both fans.[/caption]

Ben Richmond: Would you please introduce yourself?

Mû Mbana: Hello, I'm Mû Mbana from Guinea Bissau. I'm going to play tonight from my new record, which is Iñén. That means hands, at the same time it means the number 10 in Brahme. It is the ethnic group that I am from, and it is an ancient language from ancient Egypt and we still speak it in Guinea Bissau.

And what instruments will you be playing tonight?

I'm going to be playing bënsuni and simbi. The bënsuni is a common instrument from West Africa, but every country has its variation and version of the instrument. Like in Mali they call it ngoni and in Senegal they call it xalam and even in Guinea we have different names for it, but the common name for it is akonting. In my language we call it bënsuni. And the simbi is typical from Guinea-Bissau. It's like a bass. It's bigger, has four strings or three strings. Anciently it was three strings, but now we use four strings. And it's a typical instrument from Guinea-Bissau.

They're ancient instruments. They have a lot of stories and a lot of voices and a lot of things to remind us. They have a lot of memory to share with us. I think in a subjective way, they always have memories to share and things to remind us.

When did you become a musician?

I don't know if I became a musician. I mean, I've been always making music since I have memory of myself. I work with music but I don't consider myself exclusively a musician. I work with music as a way of communicating with the world. But also I do other things: I'm a researcher. So I research in different areas: scientific areas, artistic areas. The fact that I play music as a job that doesn't close me exclusively as only a musician because I study other things and I make research of other things as a source of knowledge to reach myself. Even in music I do research on the history of instruments and the changes as they pass through the centuries. And the scales, the different scales and the changes they pass through in each culture or each region. I'm in research I don't even have enough life to cover!

What scale do you play in? Do you have one exclusively?

I'm working very widely, musically speaking. The instruments I'm using them not only in a traditional way that we know them as, or that we know that they've been used, I'm using them also as a form of research. With this I mean that I'm using instruments to make them close to the voice. The voice can do things that instruments cannot do. But I'm trying to make them, to bring them closer to the vocal capacity. So I'm working with instruments in order to make them almost comfortable to go wherever the voice goes through. Not in the concept of Western harmony, but in different concepts of how to back the voice with instruments. Which is a more typical way of our region in West Africa. It's another concept of harmony.

On the bënsuniDo you play in a traditional way, from Guinea-Bissau?

Yes, I'm playing in a specifically classical way. For us that is how these instruments have been played for centuries, millenniums. They're really really old, ancient instruments. So I'm playing according to this classical tradition of West African music. In Guinea-Bissau we had a very strong old musical tradition in the old days of Malian empire. The place now called Guinea-Bissau had a great cultural center called Cabo. There are others, but Cabo was most important. And during those times, there were very great concentration of poets and instrument builders and they cultivated the art of building instruments and composing music. Most of the music of that brilliant historical, cultural moment are still the standards that we sing and play in many countries of West Africa. That's why I refer it as our classical music, because it's even older than European classical music.

How did you study this traditional music?

In the real African school, the master teaches you first to listen, and after that he teaches you the philosophy of the music and the musical way of life. And after that he teaches you to build your instrument. And after that, he teaches you to play the instrument. Playing the instrument is the last part.

And that's what gives us freedom, because we know how our instrument works. Whenever we have a problem with it, we know how to fix it. That's a lot of freedom for a musician.

I was thinking about people on tour with, say, the simbi. If you break a guitar string it's easy to replace. If you break a string on one of those...

It's not so easy as a guitar. So you have to make art. You have to make art to replace the string. It takes a bit more time. But nowadays we are using nylon strings, because it's easier and quicker, especially when you're on tour, nylon is very practical.

...And the simbi.[/caption]

Do you always play solo?

I've been working for the last 20 years in music as a professional, and I've passed through different stages. I've worked with bands, big bands. I've worked with trios. This time I'm working alone, because I'm in deep meditation of live music playing. Because now we are working under a philosophy which is: We now have finished the era of show business. By that I mean, we are not doing shows. We are not in a demonstration of what we can do in the music and with instruments. We now are working under a philosophy of collective instruction and using music as medicine consciously. So we bring music and we ask people to get involved in that construction and not only to admire, see and listen, but to get involved energetically in the construction of that sound that's happening right here, right now. So we all are together in that musical construction and we make it happen and we use it as medicine in that moment. So for this I need to work alone in this meditation until I get results from this and then start working with more people. That's why I went to the solo performance, to develop and get into the deepness of this philosophy. Because it's easier alone.

Why is it the end of the show-business era? What do you think has changed?

I think now, right now, humanity needs a kind of integrity. We as musicians have responsibilities to humanity to be true and to be conscious of what music means. There's a healing power in music and we must use it consciously to cure ourselves and cure people and cure our planet. Because right now, this moment in history, humanity needs more of this element with a medicine consciousness. So that's where we want to start from. And not only use it as a performing art where you go and perform and make people have fun. But also, to cure, energetically, the planet and mankind and stop with the lies.

Our worries right now are this: to be true in the music and to reach people through the motion and not through the visual impression and lights and all the paraphernalia of the stage. This is the most important change we're going through right now. This movement from the '40s up to now has ended. This era of "show" is in the end. We must get it from another branch now and try to do something constructive to the collective and to think in collective. How can music be useful to the collective health?

***

I left him to prepare for the show. He played for over 90 minutes, keeping the room enthralled. I don't know if there was healing, but I think everyone left felt like they had witnessed something special. When Mû Mbana plays, we are in a sacred space.

Stay tuned for more coverage from Nuits d'Afrique, and get on-the-ground updates via our Twitter.