Blog September 5, 2014

Mulatu Astatke's Journey to Find Himself

The first thing that will strike you at a concert by Mulatu Astatke, before the music even starts, is the mix of the crowd you are in. First, there are the older jazz lovers who may have come upon Astatke from his American records in the 1960s. There's the world music crowd who possibly discovered his sound via the Ethiopiques collection. The fourth of the now 28 volumes of Ethiopian music released back in 1998 blew people away with his Ethio-jazz fusion recordings from 1969-74. Then there are those who heard his hypnotic melodies as the soundtrack to Jim Jarmusch's 2005 film Broken Flowers, starring Bill Murray. Then there's an even younger crowd who have discovered him via his collaboration with the acid-jazz group the Heliocentrics on volume three of the Inspiration Information series in 2009. Literally, the room is filled with music lovers of all ages.

“It's always like that,” Astatke says, as we talked by phone not long after his sold-out show at the Festival International de Jazz de Montreal in July. “We get the youngsters, the older people, all the people, scene-goers—all kinds of people come to my concerts always. I really enjoyed the show. Really nice people, man. It was great. Really cool.”

Born in 1943, Astatke first discovered a love of music as a child—his mother taught him piano. But it wasn't until he was sent to England by his parents, specifically to go to a high school in North Wales, that he began to consider a life making music.

“I went to high school to become an engineer,” he recalls. “But then the thing was, once I got into that school—it was a very great school, and they used to teach us everything—music, dancing, math, physics, everything was included—it was there I got this chance. And then the teacher told me I have a talent in music. So that's where I started to find out about myself. The more I studied in that school, the more I found out about my talent, and then they told me if I continued studying music, I could be somebody.”

After high school, Astatke went to London's Trinity College where he studied classical music. “But I found out I couldn't be a classical musician because I'm African. So I decided I should find out what I should be. So I decided to study jazz music instead. I said, 'Jazz would be my thing!'”

http://youtu.be/qupJ1-FgfHk

Astatke and his friends would often go to clubs around London where he discovered a scene of Nigerian and Ghanaian musicians. They would sometimes let him sit in and play the congas. An interesting side note is that around the same time there was another African student at Trinity College studying music—Fela Kuti. But as he was taking in all this music, Astatke thought to himself: “How come nobody plays Ethiopian music?” And that planted the seed of somehow fusing Western jazz and his own country's musical tradition.

He left London to come to America in 1958 where he became the first African student admitted to the Berklee College of Music in Boston.

“I had a very great teacher who would always say to us, 'Be yourself,'” Astatke says. “So I was hearing this great music like Coltrane, like Miles, or Gil Evans – my favorite man. I like his voicings, his arrangements. He is one I have always respected. After I left Berklee, I would ask myself, 'How did these people become themselves? How come I don't become myself?' And I would always answer, 'I have to work hard. I have to work hard.' I left to New York and formed a group called the Ethiopian Quintet and that's where I started fusing the Ethiopian modes, the Ethiopian five-tone scales with Western 12-tone music. To fuse them both is very difficult, because 12-tone music is very high tension in their scales and modes, and I had to be really careful to know how to put it together. So yes, finally, I became myself—the father of Ethio-jazz music.”

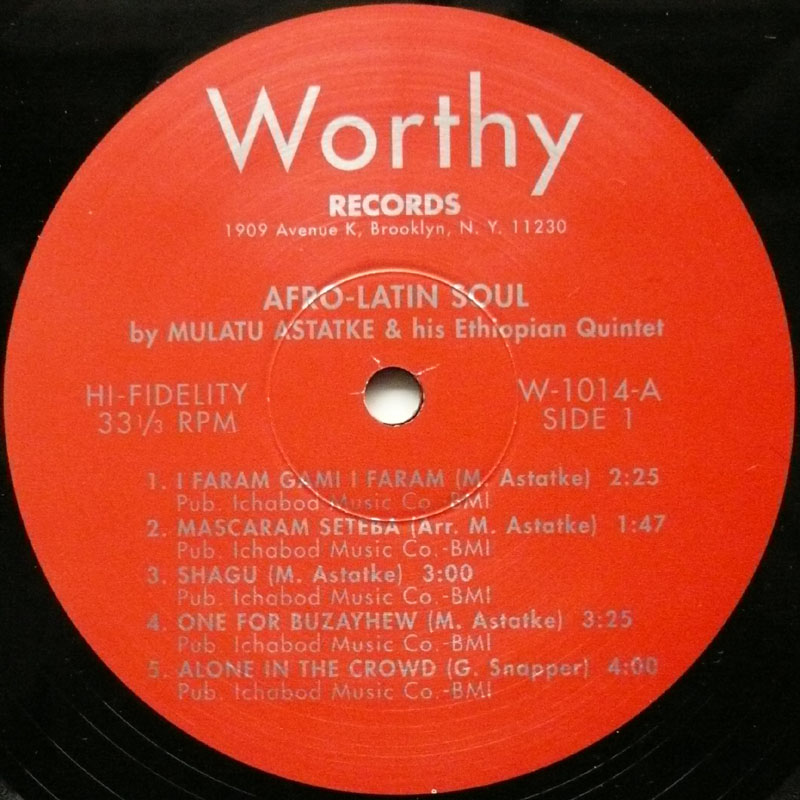

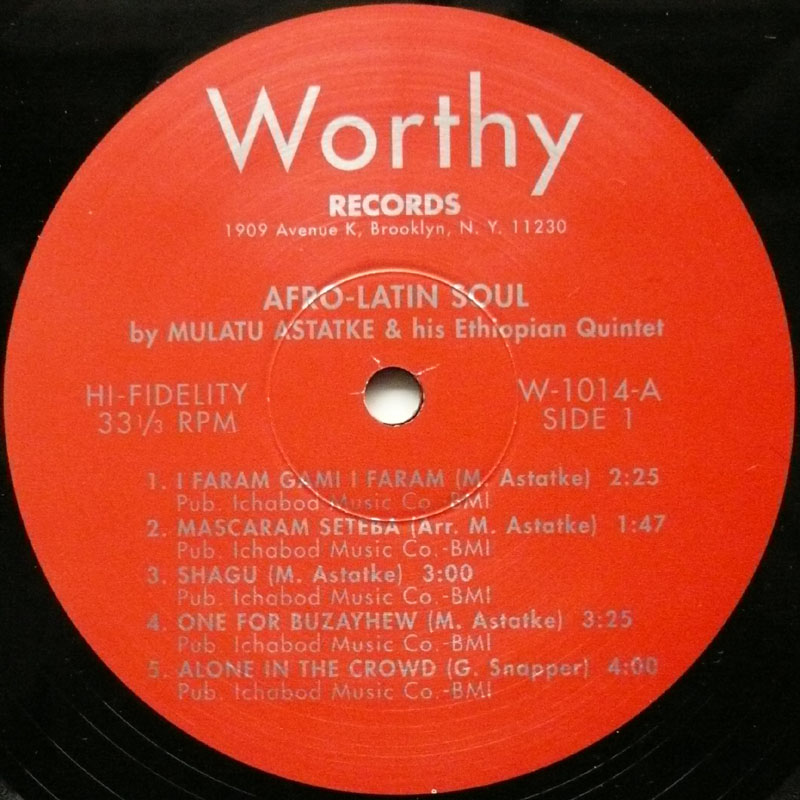

During his time in New York, he listened and played with many Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians who were also living there. In 1966, he released an album entitled Afro-Latin Soul.

“This was the thing,” he explains, “the Afro-Cuban thing is really African music. It is a development of African music. They're our brothers. So when I do my music, I never think of Latin, I always think we have those rhythms in Ethiopia. Ethio-jazz is a music fused with all kinds of interesting music from all parts of the world. But the art and beauty of Ethiopian music is on top of Ethio-jazz. So Latin is part of that.”

He returned to Ethiopia in the early 1970s, and while at first his countrymen weren't sure what to make of this new music, he soon became a cultural ambassador traveling the world and lecturing about Ethiopian culture, while at that same time sharing his experiences and teaching back home. However, by the mid-'70s, the Derg had ousted Emperor Haile Selassie and thrust the country into a decade-plus of political and social upheaval.

“Even though there was a lot going on politically,” Astatke says, “there was no problem musically, for musicians. We played what we wanted to play. We taught what we wanted to teach. I was in lot of experimental works, not just teaching. What was happening didn't affect me at all, because I was just doing music. I was also traveling a lot. So I was not there all the time. I was traveling and playing and sharing my experience with my Ethiopian brothers around the world. It was a great challenge, but I'm through it and here I am now. I think all my traveling and concerts have done so much to help people understand what Ethiopia's contribution to the world has been.”

Because Astatke's music is instrumental he was able to avoid the otherwise intense government censorship of the Derg era who were more focused on songs with politically “dangerous” lyrics.

Today, at 71 years of age, Astatke has truly “become somebody.” Not only is he playing to crowds around the world, but he continues to teach—and to learn. In 2008, he was a Radcliffe Institute Fellow at Harvard University where he began work on an opera based in part on “The Chant of St. Yared,” written around 380 A.D. by the founder of Ethiopian church music. Astatke performed the first part of the opera, conducting with a mekwamia, a traditional Ethiopian music conducting stick, there at Harvard.

“It's going to be done very soon,” he promises. “I'm working on it and it will be one of the greatest works of my music and I'm sure it's going to be great for Ethiopia as well.”

Last year saw the release of a new CD, Sketches of Ethiopia, in which he brought in Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara to join him on a track.

“It was the idea of West meeting East,” he explains. “In Mali there is a lot of connections with our scales and modes, so I wanted to show the connection with other parts of Africa. Fatou is my good sister, a great lady who I've admired for a long time. She has a great voice. So I hope to plan in the future to do more.

And most recently, he says he has been in Brazil performing with local singer/rapper Criolo, with whom he hopes to do some recording soon.

“We call it Ethio-Brazilian fusion,” Astatke says. “It's beautiful. Criolo is one of the top Brazilian singers. We did some beautiful stuff. We are going to record it very soon, but right now we're doing about six concerts all over the place, which is so beautiful.”

And if all that isn't enough, he concludes, “I just lectured here in London at the Royal Albert Hall for the National Geographic about the Ethiopian contributions to the world. So this is what I do now. So I'm quite, quite busy, my friend. I think musicians can never be satisfied. We always want to be more, experiment more. My next CD will be even more different.”

First two photos by Frédérique Ménard-Aubin

During his time in New York, he listened and played with many Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians who were also living there. In 1966, he released an album entitled Afro-Latin Soul.

“This was the thing,” he explains, “the Afro-Cuban thing is really African music. It is a development of African music. They're our brothers. So when I do my music, I never think of Latin, I always think we have those rhythms in Ethiopia. Ethio-jazz is a music fused with all kinds of interesting music from all parts of the world. But the art and beauty of Ethiopian music is on top of Ethio-jazz. So Latin is part of that.”

He returned to Ethiopia in the early 1970s, and while at first his countrymen weren't sure what to make of this new music, he soon became a cultural ambassador traveling the world and lecturing about Ethiopian culture, while at that same time sharing his experiences and teaching back home. However, by the mid-'70s, the Derg had ousted Emperor Haile Selassie and thrust the country into a decade-plus of political and social upheaval.

“Even though there was a lot going on politically,” Astatke says, “there was no problem musically, for musicians. We played what we wanted to play. We taught what we wanted to teach. I was in lot of experimental works, not just teaching. What was happening didn't affect me at all, because I was just doing music. I was also traveling a lot. So I was not there all the time. I was traveling and playing and sharing my experience with my Ethiopian brothers around the world. It was a great challenge, but I'm through it and here I am now. I think all my traveling and concerts have done so much to help people understand what Ethiopia's contribution to the world has been.”

Because Astatke's music is instrumental he was able to avoid the otherwise intense government censorship of the Derg era who were more focused on songs with politically “dangerous” lyrics.

Today, at 71 years of age, Astatke has truly “become somebody.” Not only is he playing to crowds around the world, but he continues to teach—and to learn. In 2008, he was a Radcliffe Institute Fellow at Harvard University where he began work on an opera based in part on “The Chant of St. Yared,” written around 380 A.D. by the founder of Ethiopian church music. Astatke performed the first part of the opera, conducting with a mekwamia, a traditional Ethiopian music conducting stick, there at Harvard.

“It's going to be done very soon,” he promises. “I'm working on it and it will be one of the greatest works of my music and I'm sure it's going to be great for Ethiopia as well.”

Last year saw the release of a new CD, Sketches of Ethiopia, in which he brought in Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara to join him on a track.

“It was the idea of West meeting East,” he explains. “In Mali there is a lot of connections with our scales and modes, so I wanted to show the connection with other parts of Africa. Fatou is my good sister, a great lady who I've admired for a long time. She has a great voice. So I hope to plan in the future to do more.

And most recently, he says he has been in Brazil performing with local singer/rapper Criolo, with whom he hopes to do some recording soon.

“We call it Ethio-Brazilian fusion,” Astatke says. “It's beautiful. Criolo is one of the top Brazilian singers. We did some beautiful stuff. We are going to record it very soon, but right now we're doing about six concerts all over the place, which is so beautiful.”

And if all that isn't enough, he concludes, “I just lectured here in London at the Royal Albert Hall for the National Geographic about the Ethiopian contributions to the world. So this is what I do now. So I'm quite, quite busy, my friend. I think musicians can never be satisfied. We always want to be more, experiment more. My next CD will be even more different.”

First two photos by Frédérique Ménard-Aubin

During his time in New York, he listened and played with many Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians who were also living there. In 1966, he released an album entitled Afro-Latin Soul.

“This was the thing,” he explains, “the Afro-Cuban thing is really African music. It is a development of African music. They're our brothers. So when I do my music, I never think of Latin, I always think we have those rhythms in Ethiopia. Ethio-jazz is a music fused with all kinds of interesting music from all parts of the world. But the art and beauty of Ethiopian music is on top of Ethio-jazz. So Latin is part of that.”

He returned to Ethiopia in the early 1970s, and while at first his countrymen weren't sure what to make of this new music, he soon became a cultural ambassador traveling the world and lecturing about Ethiopian culture, while at that same time sharing his experiences and teaching back home. However, by the mid-'70s, the Derg had ousted Emperor Haile Selassie and thrust the country into a decade-plus of political and social upheaval.

“Even though there was a lot going on politically,” Astatke says, “there was no problem musically, for musicians. We played what we wanted to play. We taught what we wanted to teach. I was in lot of experimental works, not just teaching. What was happening didn't affect me at all, because I was just doing music. I was also traveling a lot. So I was not there all the time. I was traveling and playing and sharing my experience with my Ethiopian brothers around the world. It was a great challenge, but I'm through it and here I am now. I think all my traveling and concerts have done so much to help people understand what Ethiopia's contribution to the world has been.”

Because Astatke's music is instrumental he was able to avoid the otherwise intense government censorship of the Derg era who were more focused on songs with politically “dangerous” lyrics.

Today, at 71 years of age, Astatke has truly “become somebody.” Not only is he playing to crowds around the world, but he continues to teach—and to learn. In 2008, he was a Radcliffe Institute Fellow at Harvard University where he began work on an opera based in part on “The Chant of St. Yared,” written around 380 A.D. by the founder of Ethiopian church music. Astatke performed the first part of the opera, conducting with a mekwamia, a traditional Ethiopian music conducting stick, there at Harvard.

“It's going to be done very soon,” he promises. “I'm working on it and it will be one of the greatest works of my music and I'm sure it's going to be great for Ethiopia as well.”

Last year saw the release of a new CD, Sketches of Ethiopia, in which he brought in Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara to join him on a track.

“It was the idea of West meeting East,” he explains. “In Mali there is a lot of connections with our scales and modes, so I wanted to show the connection with other parts of Africa. Fatou is my good sister, a great lady who I've admired for a long time. She has a great voice. So I hope to plan in the future to do more.

And most recently, he says he has been in Brazil performing with local singer/rapper Criolo, with whom he hopes to do some recording soon.

“We call it Ethio-Brazilian fusion,” Astatke says. “It's beautiful. Criolo is one of the top Brazilian singers. We did some beautiful stuff. We are going to record it very soon, but right now we're doing about six concerts all over the place, which is so beautiful.”

And if all that isn't enough, he concludes, “I just lectured here in London at the Royal Albert Hall for the National Geographic about the Ethiopian contributions to the world. So this is what I do now. So I'm quite, quite busy, my friend. I think musicians can never be satisfied. We always want to be more, experiment more. My next CD will be even more different.”

First two photos by Frédérique Ménard-Aubin

During his time in New York, he listened and played with many Puerto Rican and Cuban musicians who were also living there. In 1966, he released an album entitled Afro-Latin Soul.

“This was the thing,” he explains, “the Afro-Cuban thing is really African music. It is a development of African music. They're our brothers. So when I do my music, I never think of Latin, I always think we have those rhythms in Ethiopia. Ethio-jazz is a music fused with all kinds of interesting music from all parts of the world. But the art and beauty of Ethiopian music is on top of Ethio-jazz. So Latin is part of that.”

He returned to Ethiopia in the early 1970s, and while at first his countrymen weren't sure what to make of this new music, he soon became a cultural ambassador traveling the world and lecturing about Ethiopian culture, while at that same time sharing his experiences and teaching back home. However, by the mid-'70s, the Derg had ousted Emperor Haile Selassie and thrust the country into a decade-plus of political and social upheaval.

“Even though there was a lot going on politically,” Astatke says, “there was no problem musically, for musicians. We played what we wanted to play. We taught what we wanted to teach. I was in lot of experimental works, not just teaching. What was happening didn't affect me at all, because I was just doing music. I was also traveling a lot. So I was not there all the time. I was traveling and playing and sharing my experience with my Ethiopian brothers around the world. It was a great challenge, but I'm through it and here I am now. I think all my traveling and concerts have done so much to help people understand what Ethiopia's contribution to the world has been.”

Because Astatke's music is instrumental he was able to avoid the otherwise intense government censorship of the Derg era who were more focused on songs with politically “dangerous” lyrics.

Today, at 71 years of age, Astatke has truly “become somebody.” Not only is he playing to crowds around the world, but he continues to teach—and to learn. In 2008, he was a Radcliffe Institute Fellow at Harvard University where he began work on an opera based in part on “The Chant of St. Yared,” written around 380 A.D. by the founder of Ethiopian church music. Astatke performed the first part of the opera, conducting with a mekwamia, a traditional Ethiopian music conducting stick, there at Harvard.

“It's going to be done very soon,” he promises. “I'm working on it and it will be one of the greatest works of my music and I'm sure it's going to be great for Ethiopia as well.”

Last year saw the release of a new CD, Sketches of Ethiopia, in which he brought in Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara to join him on a track.

“It was the idea of West meeting East,” he explains. “In Mali there is a lot of connections with our scales and modes, so I wanted to show the connection with other parts of Africa. Fatou is my good sister, a great lady who I've admired for a long time. She has a great voice. So I hope to plan in the future to do more.

And most recently, he says he has been in Brazil performing with local singer/rapper Criolo, with whom he hopes to do some recording soon.

“We call it Ethio-Brazilian fusion,” Astatke says. “It's beautiful. Criolo is one of the top Brazilian singers. We did some beautiful stuff. We are going to record it very soon, but right now we're doing about six concerts all over the place, which is so beautiful.”

And if all that isn't enough, he concludes, “I just lectured here in London at the Royal Albert Hall for the National Geographic about the Ethiopian contributions to the world. So this is what I do now. So I'm quite, quite busy, my friend. I think musicians can never be satisfied. We always want to be more, experiment more. My next CD will be even more different.”

First two photos by Frédérique Ménard-Aubin