Over the year-end holidays, I get a chance to catch up with music, listening to old stuff I truly love and have no need to write about, but also catching up with things that went by too fast in the prior year or that are looming large for the coming one. This time around, I got to thinking about music and activism. 2020 promises to be a year of arduous activism on many fronts, so it’s no surprise that we are seeing musical projects aiming to inspire engagement and commitment to improving our earthly lot in the face of old and new struggles and a seemingly darkening horizon. Musical activism is on the rise, but one has to wonder: Does it do any good? It’s a question I have often asked musicians who seek to bring about change through their art. The typical answer is that music touches people as nothing else can. True, but does it actually lead to change?

I don’t mean to be cynical. Clearly there are circumstances in which music has changed the course of history. Our civil rights movement and the fight against apartheid in South Africa come to mind. But these examples are situation specific. What about grander, global ambitions like…well, world peace!

That’s the title of a recent compilation from the masters of compilation at Putumayo World Music. It’s a set of 11 moving songs, none of them particularly new, by a broad variety of artists expressing a deep longing for peace. A key inspiration for this project was John F. Kennedy’s 1963 speech inaugurating the Peace Corps. Kennedy evokes a peace “based not on a sudden revolution in human nature but on a gradual evolution in human institutions.” His dry-eyed, clear-headed and acutely reasonable vision suited the time when a society moving away from world war (or so it seemed) was in a mood to dream big. JFK’s words still ring true today, and how reassuring it would feel to hear such words from a current president…. Said Kennedy, “Genuine peace must be the product of many nations, the sum of many acts. It must be dynamic, not static, changing to meet the challenge of each new generation. For peace is a process.”

All of the songs in this collection are worth knowing and remembering, from India Arie’s “One” (2013) calling for unity among the world’s religions, to Jackson Browne’s “It Is One” (1996) with its reminder that the earth is indeed a singularity, to Xhosa artist Bongeziwe Mabandla’s Afro-folk plea, “Freedom For Everyone” (2012), which needs no explication. These are songs of high-flung aspiration, sincere and heartfelt, but so grand in their visions that it is hard to connect them with reality. Other songs are more situational. Keb' Mo'’s 2001 country-rock tinged remake of the O’Jays’ classic “Love Train” is also grandiose, but because it was penned in 1972, it evokes a moment when the Cold War and the struggle between Israel and Egypt dominated the news.

David Broza—more or less Israel’s Bob Dylan—collaborates with Wyclef Jean on “East Jerusalem/West Jerusalem” (2013). The song was part of a larger project Broza organized and recorded in East Jerusalem. There’s palpable anguish here, but this world-weary soul wonders how many songs and projects have been dedicated to this particular peace effort, without much result. No reason to stop, but in this case, the bar for effective musical activism is high indeed.

Then there are songs that directly call for action, like Keb' Mo'’s 2004 “Wake Up Everybody,” a crisp, perky gospel-tinged pop song that opens this collection. The message is, “World won’t get no better if we don’t change…you and me.” In other words, it’s on us! From another universe, but also clearly directive, is “Think of Others” (2016) by Mira Awad. Awad was raised in Israel by a Christian Arab father and a Bulgarian mother. She has that kind of hybrid identity that allows her to straddle divides, but makes it hard to pick sides. Her voice, singing in Arabic, is strong with the nuances of Arabic traditional vocal style, but also has a pleasing pop edge. The song’s message actually comes from a poem by the iconic Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish. Its reference to “people of the camps” is a tell. Maybe it’s not so hard to pick sides after all, but the message remains artfully neutral and universal.

The songs that touch me most here are the personal ones. Nina Simone initially resisted musical protest, finding it simplistic and hollow. But in 1967, amid the fires of the civil rights movement, she sang “I Wish I Knew How it Would Feel to Be Free.” This song really hits home with its gospel punch and, of course, Simone’s devastatingly affecting voice. But here, the aspiration is her own, not the world’s, and somehow that cuts deeper.

Then there’s Richard Bona and Michael Brecker’s 1995 take on Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song.” It’s worth recalling that Marley penned this song shortly after he was diagnosed with cancer. The notion that such songs were “all I ever had” is heartbreakingly plain and honest. Redemption songs are not a curative for the world’s problems, but a balm for those who must suffer them. There’s a note of resignation in Marley’s words, made all the more poignant by his own imminent demise, likely hastened by his resistance to medically advised treatment. You feel he knew what was coming and accepted it. Bona sings beautifully in his own language leaving the chorus in English. Brecker’s saxophone is a tad saccharine, but it’s a beautiful homage to a timeless anthem.

The collection ends with another timeless anthem, John Lennon’s “Imagine,” rendered here in 2011 by Playing for Change. Mark Johnson’s visionary concept of having musicians from all over the world collaborate virtually on well-known songs amounts to a laudable and concrete form of musical activism all on its own, even though the formula works better on other Playing for Change efforts. But what hits me is that Lennon’s dream of “no religion” still has the power to shock, particularly nestled among songs deeply empowered by faith traditions. I suppose one way that people of faith have been able to embrace “Imagine” so universally is that you can take the song not as a prescription, but as a thought exercise, and for now, sadly, that seems to be the nature of world peace itself.

As artful as this compilation is, it is just that, a compilation of existing work. A more ambitious form of musical activism is the sort where artists come together to create anew, and address the challenges of their time. This would be the “We Are the World” Global Citizen/Farm Aid approach. Here, I briefly note that there is a wonderful example of this sort of collaboration about to arrive on the scene. In 2018, Jackson Browne assembled a coalition of artists from four countries—including dear friends of Afropop Worldwide Habib Koite, Raul Rodriguez and Paul Beaubrun—to record songs together under the banner Artists for Peace and Justice. The session took place in Haiti, hence the title Let the Rhythm Lead: Haiti Song Summit, Vol. 1. Activism aside, there’s some wonderful music here and I will have much more to say about this project when the album drops later this month.

But I end with a very different type of musical activism, one that aims not to voice grand aspirations or move souls with beautifully polished songs, but rather to use music itself to change the lives of young people.

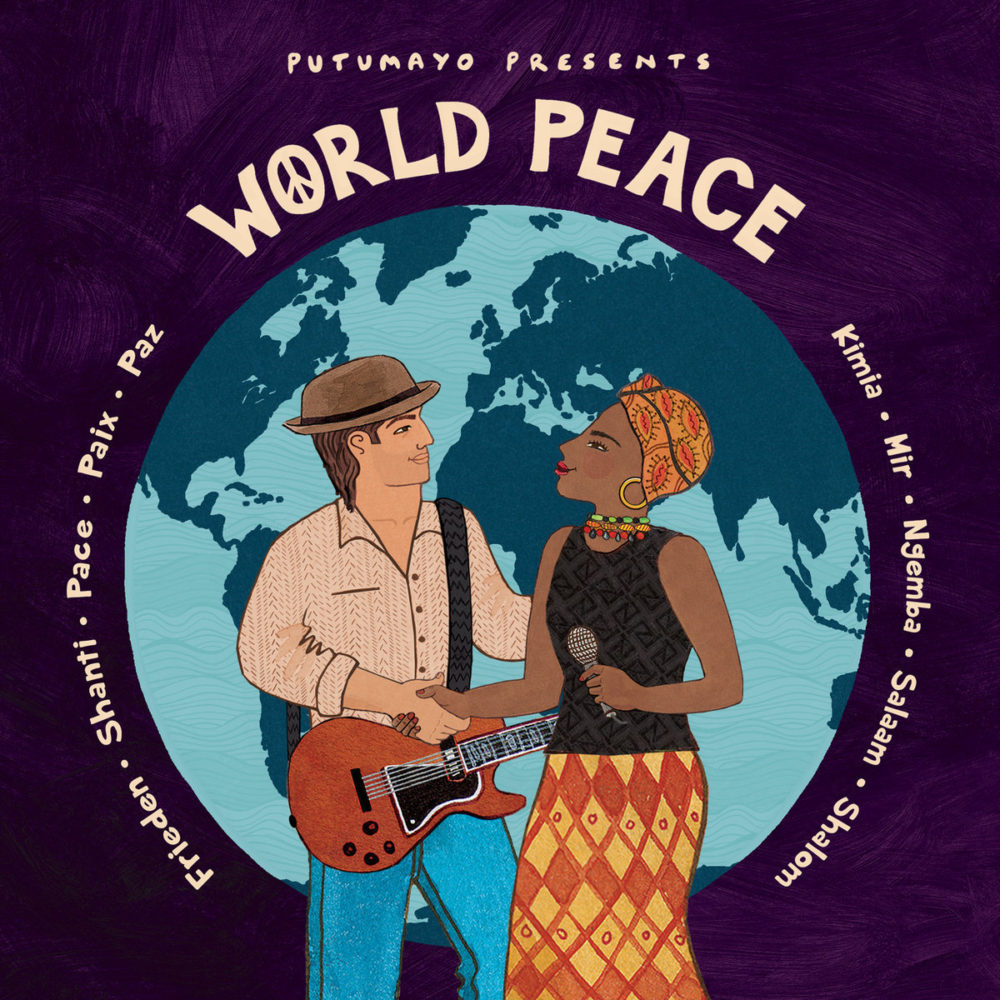

Sylvain Leroux is a composer, bandleader and specialist in the West African Fulani flute known as tambin. Leroux has been a fixture of the New York music scene for many years, and has appeared on Afropop Worldwide, airing his deep knowledge of this unique tradition. Six years ago, he returned to Conakry, Guinea, where he learned his art and began a partnership with the Centre Tyabala Théâtre de Guinée, creating within it a school of Fula flute. He recently released an album called Tyabala, recorded with the teachers and students who have been studying there. These are mostly poor kids, even street kids, who would be most unlikely to take on the challenge of playing tambin under any other circumstances, and it is truly moving to hear how well they have learned.

This is not a sophisticated studio recording. The balance of instrument volumes can vary; kora, notoriously hard to record well, falls to the background at times, and there’s a roominess to the overall sound. But that’s really its charm. You can feel the surround of an echoey African space, the very space in which these boys and girls have studied and honed their considerable skills. On some songs, as many as six tambin play together, some keeping to the accompaniment and others taking wild improvisatory solos. There’s nothing quite like the cries and growls of a Fula flute in full flight. Think Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson in overdrive with an African twist.

Many of these 14 songs feature what sounds like the entire cadre of child students belting out robust choral vocals. There’s a track showcasing Leroux’s signature chromatic tambin played by one particularly talented boy. The song is Sidney Bechet’s “Petite Fleur” set to an African 6/8 beat. There is also a 14-minute, djembe-driven percussion piece that culminates in a clattering climax in which you can feel the slap back of what must be concrete walls.

As I say, Tyabala is not for audiophiles, but when it comes to music that actually seems to be making a difference in this troubled world, it’s hard to beat, perhaps part of the “gradual evolution” JFK evoked more than a half-century ago.