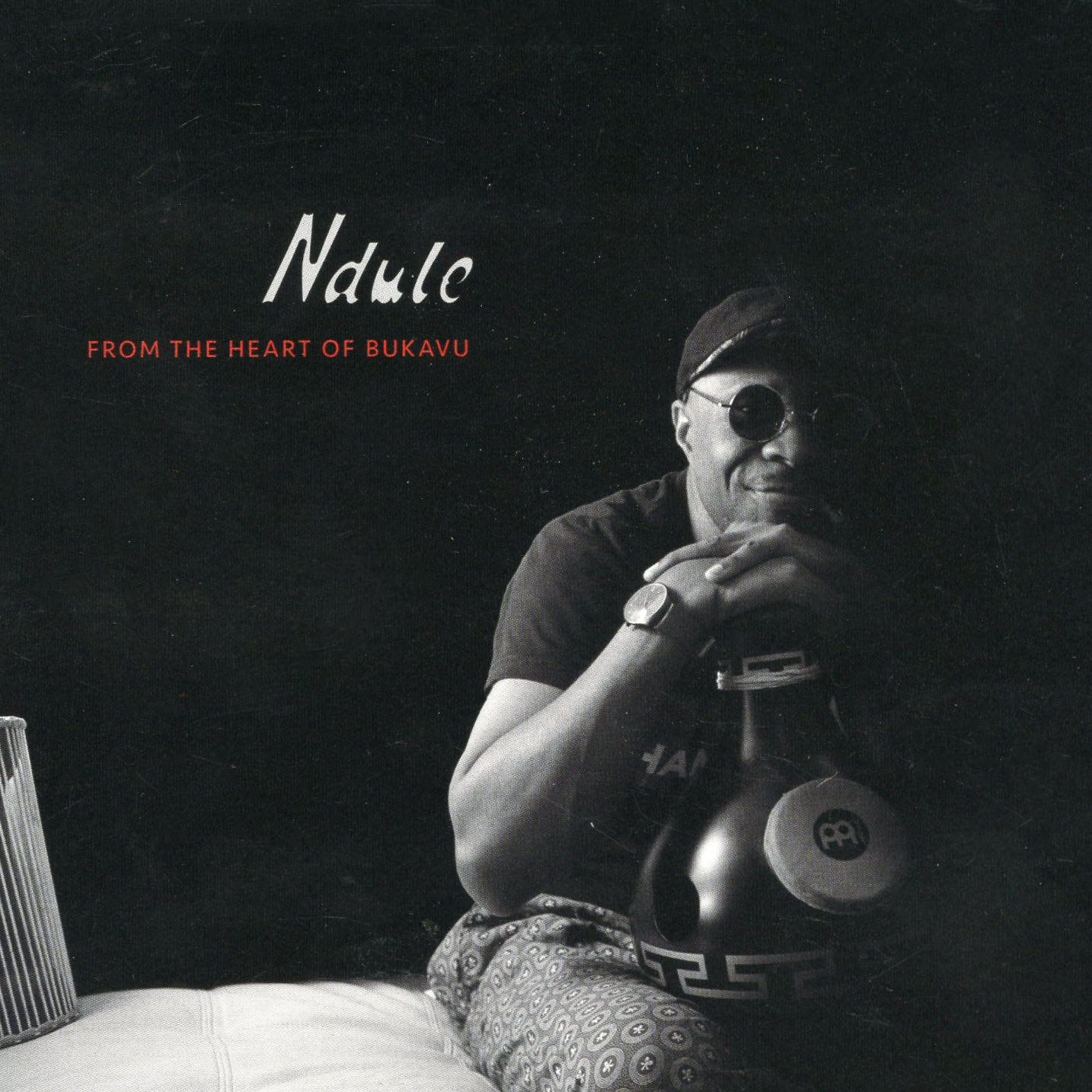

John "Jaja" Bashegezi’s music reflects his journey through life from the Congo to East Africa to America. He’s a guitarist and singer of natural grace who has mastered the sensuous guitar style and mellifluous Lingala vocals of classic Congolese music, but also expanded his music as he has traveled through life. Born in Bukavu in the war-torn eastern Congo, he became a refugee in the 1990s. Fleeing with his guitar, he found work as a studio musician in Kampala, Uganda, encountering the great Congolese singer Samba Mapangala and hooking into the local scene. (All these years later, Bashengezi performs in Mapangala's U.S. band.) Bashengezi’s odyssey eventually landed him in the vicinity of Washington, DC, where he has made alliances with a number of other African musicians, but also developed the uniquely personal style showcased on this album.

These 15 acoustic songs blend flavors of east, west and central Africa. They brim with gentle eloquence whether Bashengezi sings alone with his guitar on the poignant ballad “Na Sengi,” or fills out a multiguitar Congolese rumba mesh with warm vocal harmonies as on “Maka Wewe,” a song of self-empowerment. “Kali,” a minor-key gem with ornaments of muted guitar and softly fluttering flute, tells a village story of bad behavior and witchcraft. At moments here, Bashengezi’s vocal comes close to the softer side of the late, great Papa Wemba. Percussion on these tracks is light and tasteful, featuring wood block pulses, deep hand drum accents, and clapping. Two songs—“I Miss Home,” a lilting rumba instrumental, and “Bayaka Pygmee”—evoke forest scenarios the singer recalls from his youth, especially the latter, an artful adaptation of Bayaka polyphonic vocals that reveals surprising new colors in Bashengezi’s fine voice.

Two tracks are sung in English, “Refugee,” in which Bashengezi alludes to his personal story, and “Shoulder to Shoulder,” an ode to brotherhood. But overall, the Western folk/pop sensibility heard on so many African acoustic projects is pleasantly absent here. Bashengezi’s voice has the smooth polish of a Lokua Kanza or Richard Bona, but the music is more folkloric, full of warm, entrancing cycles and enveloping soundscapes of plucked nylon strings and, here and there, metal prongs. Among those plucked strings, we hear West African ngoni (“Fata Katibu,” which calls out politicians who cling to power) and kora, (“Maji,” a song about water). Both of these songs subtly infuse Mande musical sensibility into the Congolese mix.

“Amina,” a praise song to an HIV-positive woman, showcases an East African harp, likely Ugandan, although the album notes do not identify the accompanists. A silken Ugandan influence is an undertone throughout; the artist fittingly credits Samite as an “inspiration.” But all these influences are filtered through the timeless lyricism and sensuality of Congolese music, and the result is quite special, one of the best acoustic African releases I’ve heard in a long time.