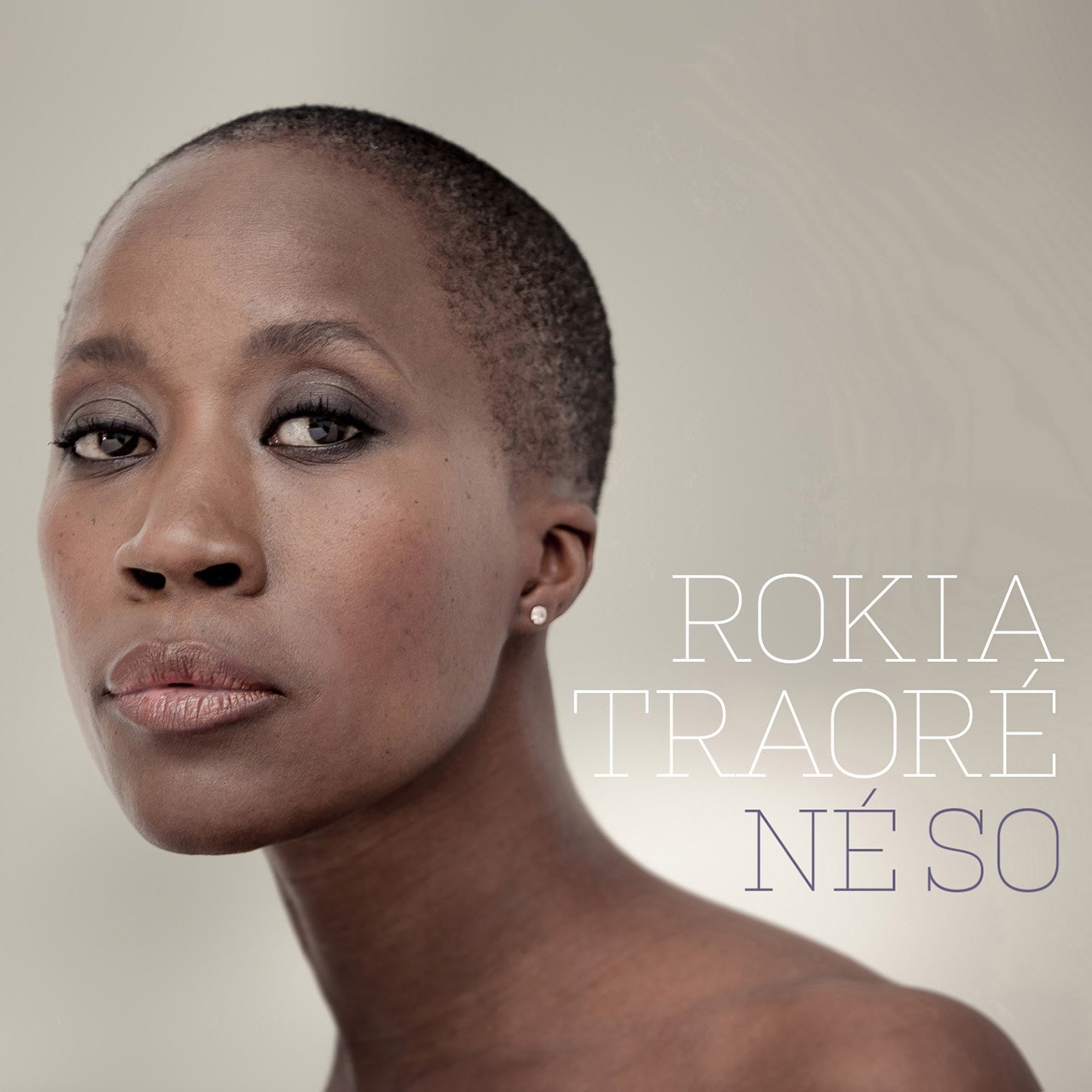

It takes all of about four seconds of the first track of Né So for Rokia Traoré's voice to come in and transfix the listener. Her latest album is mostly a mellow affair, wherein Traoré-the-arranger steps aside to make room for Traoré-the-vocalist. Whether using French, Bambara or English, the Malian singer always sounds regal, even when affecting a confessional whisper.

Featuring musicians from three different West African countries and recorded in Belgium and the U.K., the album slips around musical styles. The ngoni makes a few tasteful appearances, played by Mamah Diabaté, but the arrangements are generally kept spare. The guitars sometimes lap with Tuareg-inspired desert blues and sometimes shimmer with vibrato as though Ry Cooder had stopped by. John Paul Jones, of Led Zeppelin fame, plays bass. Unlike Traoré's previous album Beautiful Africa, the percussion is mostly kept in the background.

The songs are mostly love songs or calls for goodness, so gentle and accommodating it can be hard to remember the circumstances that bore them: Traoré had moved back to Mali in 2009, only to leave again with her son when unrest shook the country in 2012. Né so means home, and as the album goes on, she seems to mourn for Mali. The standout track, “Kolokani,” ends with a wish to those who have stayed in the titular ancestral village that the singer “thinks of Mali.”

The last two songs are humanitarian missives about refugees, and the desire to see us as one world, respectively. The second song is in English and boasts guest appearances from Devendra Banhart and the American author Toni Morrison, praising diversity and the quality of human respect. Given what has happened in Traoré's home country, it's an understandable, timely and certainly important message. Unfortunately, the language used to deliver this message veers close to platitude.

Contrast that with her haunting cover of “Strange Fruit.” While the song, popularized and immortalized by Billie Holiday, is an American standard, Traoré's interpretation brings out the hurt, the violence of racism, singing over just guitar and bass. Though the song dates back to the 1930s, Traoré's version reminds us, sickeningly, that the past isn't even past. Calling for unity is good, but sometimes it is more effective to show the ugly consequences of hatred. On an album that's front to back so beautiful and gentle, the brutality hits hard.