We don’t see a see a lot of Sudanese music on the market. Even the country’s greatest legacy artists, like the late Mohamed Wardi, have scarcely made a name in the West. The exiled rapper Emmanuel Jal has a vigorous international career, but not based in Sudan. He fled South Sudan well before 2011 when its people voted to hive off as a separate (and still divided) country. This chaotic history, recounted in Afropop’s Music and History in the Two Sudans, surely helps explain Sudan’s low profile in global music. And this is sad, because this is a country with unique and beautiful musicality.

Four current releases of Sudanese music, mostly from the archives, make the point forcefully. Two Niles to Sing A Melody: The Violins and Synths of Sudan (Ostinatto) is as good a compilation as you will find of “golden era” Sudanese music: swinging big bands backing a mellifluous, usually male, vocalist with a robust and quirky parlay between accordion-like synth, violins and saxophone-led brass. This innovative era (roughly 1960-83) parallels the “golden era” in neighboring Ethiopia’s music, and in some ways, the two are similar. Sudan’s swing has a bit more Anglo squareness in its romping 4/4 rhythms and polite arrangements. But the spirit of fusing local tradition with savvy borrowings from international pop trends produced spectacular results in both cases.

The Khartoum scene lasted longer, right up to the imposition of Sharia law in 1983, nearly a decade after the boot of military rule came down in Addis Ababa. Most of the great Sudanese recordings were made across the Nile River from Khartoum in Omdurman, where the radio studios were. It was clearly a place of joyful creativity, where pioneering orchestrators invented new formulas and delighted a young nation.

Two Niles is a double CD sampling 15 artists in 16 tracks. Wardi gets two tracks, and deservedly so. “Al Sourah (The Photo)” conjures all the drama of an epic film score with brooding orchestration in which violin and synth converse gracefully, setting up Wardi’s velvety tenor voice with its arresting clarity and perfect articulation. “Al Mursal (The Messenger)” has a similar flow, extended over nearly 12 minutes and showcasing electric guitar as an orchestral voice.

And there is so much more. “Al Bareedo Ana (The One I Love)” opens with loping clop of percussion, mimicking the gate of a camel as in far-older traditional fare. From there, an intricate interaction between Emad Youssef’s lithe, thin voice and a sax-led brass section blended with accordion-like synth is pure magic. “Alamy Wa Shagiya (My Pain and Suffering)” features a rare female vocal from Hana Bulu Bulu, pairing her reedy voice with a synth patch that sounds for all the world like a kazoo.

There is playfulness here, but also angst and darkness, as on “Malo Law Safeetna Inta (What If You Resolve What's Between Us)” in which Khojali Osman’s expressive voice breaks with emotion. On a few songs the listener nearly drowns in heavy washes of synths and strings, but it’s easy to be seduced into these waters. The collection also comes with an extensive booklet providing vivid accounts of Sudan in this era and the memorable artists it produced.

This summer saw the release of Kamal Keila’s Muslims and Christians (Habibi Funk). Once called the Fela Kuti or James Brown of Sudan, Kamal Keila never actually recorded a commercial album. His career heyday in the 1970s was enjoyed entirely through live performances and national radio sessions, the masters of which have disappeared. But, ever curious, the Habibi Funk label found Keila himself in a modest Khartoum home and learned that he had two reels of radio tracks from a session in 1992. Their condition did not look promising, but the tapes played, and that’s what we have here: 10 songs, five in English and five in Arabic, showcasing an artist we might never have known otherwise.

The English songs are novel for their overt borrowings from James Brown (“Agricultural Revolution”) and Chicago blues (“Shmasha”), and their earnest lyrics about African unity, and ironically, Sudanese unity. The title track, “Muslims and Christians,” makes a heartfelt, if sadly outdated, case for the affinities between the North and South: We are one nation. But there’s the cry of the blues here too, and Keila’s robust voice slices satisfyingly through grooves of bass, guitar, drums and brass.

“Ghali Ghali Ya Jinub” begins as ambling reggae, then shifts into a related Sudanese rhythm with Keila shouting out to the ancient kingdom of Nubia. “African Unity” is also reggae, more in the Bob Marley mold. “Ajmal Alyam” opens slow and sultry, then lifts into a lively trumpet-driven romp. The album is full of inventive, playful arrangements. Keila is a versatile vocalist. When he’s not channeling James Brown or crooning bluesy, he can weave his way through vocal melisma reminiscent of Ethiopian music, which clearly influenced Sudan’s own golden era sounds. On the album closer, “Ya Shaifni,” the band adapts Ethiopia’s rolling 12/8 chic-chic-ka rhythm. Keila is all about making connections, and though he appears to be long retired, this music furthers that mission, despite its anachronisms.

Also just out is The Scorpions and Saif Abu Bakr, Jazz, Jazz, Jazz (Habibi Funk). Generally overlooked as a footnote in the Sudanese music story, the Scorpions clearly had something going in the late '70s and early '80s: tight brass, funky grooves, a variety of vocal and instrumental pieces. The Scorpions dispersed after this recording was made. Saif Abu Bakr stayed in Kuwait. Others returned to Khartoum where president Nimeiry instituted Shariah law in 1983, curtailing most musical activity. As it happens, Saif returned to Sudan this year, and the band reassembled to rehearse. Perhaps another chapter will yet unfold.

“Jazz” is not exactly jazz as we know it. Many African bands of this era used the word in their name, and it was mostly a nod to American aesthetics, and usually, a clue that there’s brass in the act. Which is certainly the case here. We start out with two sax-led instrumentals, one cool and swanky, the next built around a funky 12/8 guitar vamp. Saif Abu Bakr is not the smoothest vocalist around, certainly no Wardi, but what he may lack in polish he makes up in verve and passion, with soul bravado on the driving “Farrah Galbi Aljadeed,” and channeling Franco’s dry quasi-rapping manner on the Congolese-flavored "Bride of Afrika," (although this just might be Osman Zeeto, who is featured on the track).

The grooves and styles this band moves through highlight the freeform experimentation of the era. The melody on “Forssa Saeeda” echoes the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” though the groove is closer to the Staples Singers’ “I’ll Take You There.” “Nile Waves,” another instrumental, has the cool chug of Afrobeat with drumming reminiscent of Tony Allen. The album ends with “Hilwa ya amoora,” a slow-burn pop song showcasing the more melodious side of Saif Abu Bakr’s vocal. Word is the Scorpions recently reassembled to rehearse and test the waters. Perhaps a true revival is in the works.

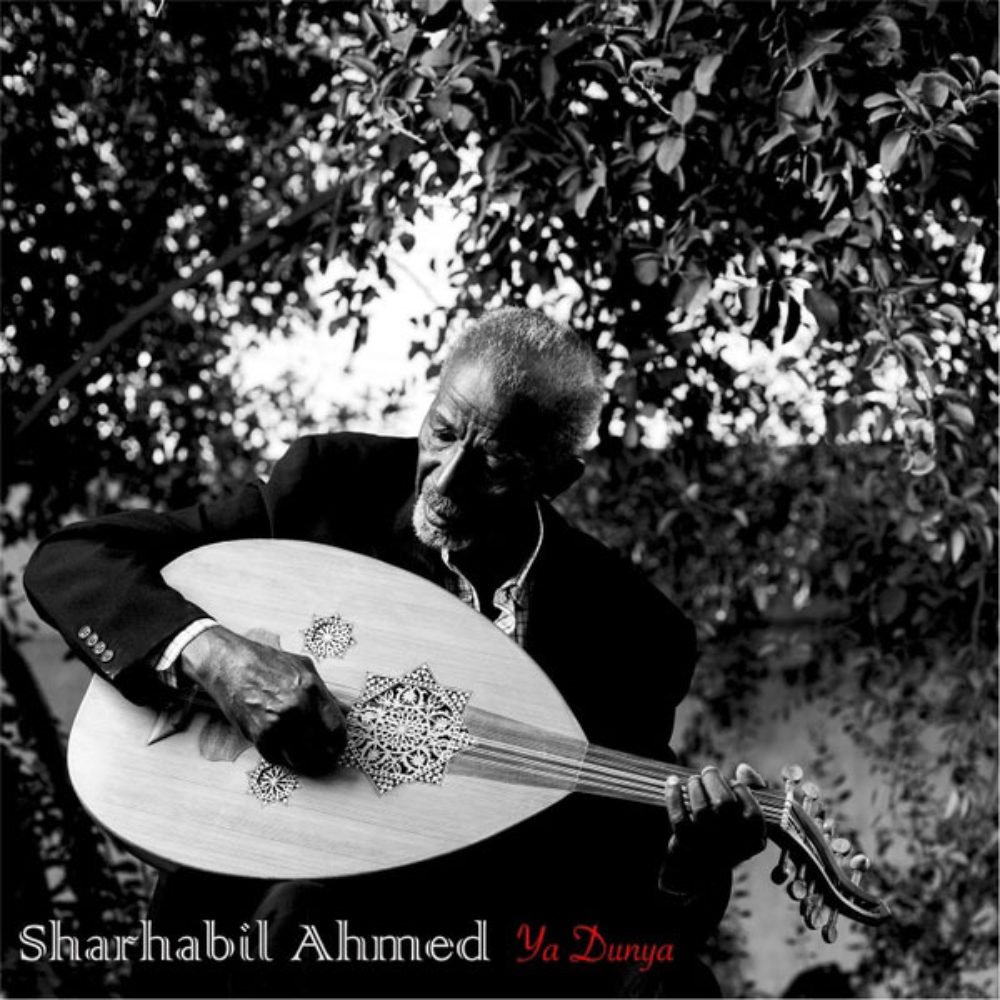

Finally, a new release from Sharhabil Ahmed, long ago dubbed “the King of Sudanese jazz.” The album is Ya Dunya (Noba Records), and while it bears no real resemblance to the Scorpions’ sound, it still doesn’t sound like jazz as we know it. Sharhabil is an oud player and vocalist with a softly lulling voice and gentle touch on the oud. The first of these five tracks, “Jannat Elhub,” is the weakest, stilted by rigid drum machine rhythm and synths that lack the charm of the golden era variety. But from there, things improve greatly, with “Bulbultain,” a solo piece graced with a grand, sweeping melody. Here, Ahmed’s supple voice perfectly blends with his jangling oud accompaniment.

The remaining three pieces feature an ensemble reminiscent of the old Omdurman days, but with a more acoustic feeling, and oud up front. These tracks build to satisfying emotional crescendos. This is a nice entrée into the work of a major Sudanese recording artist, still very much on the scene.

Related Audio Programs