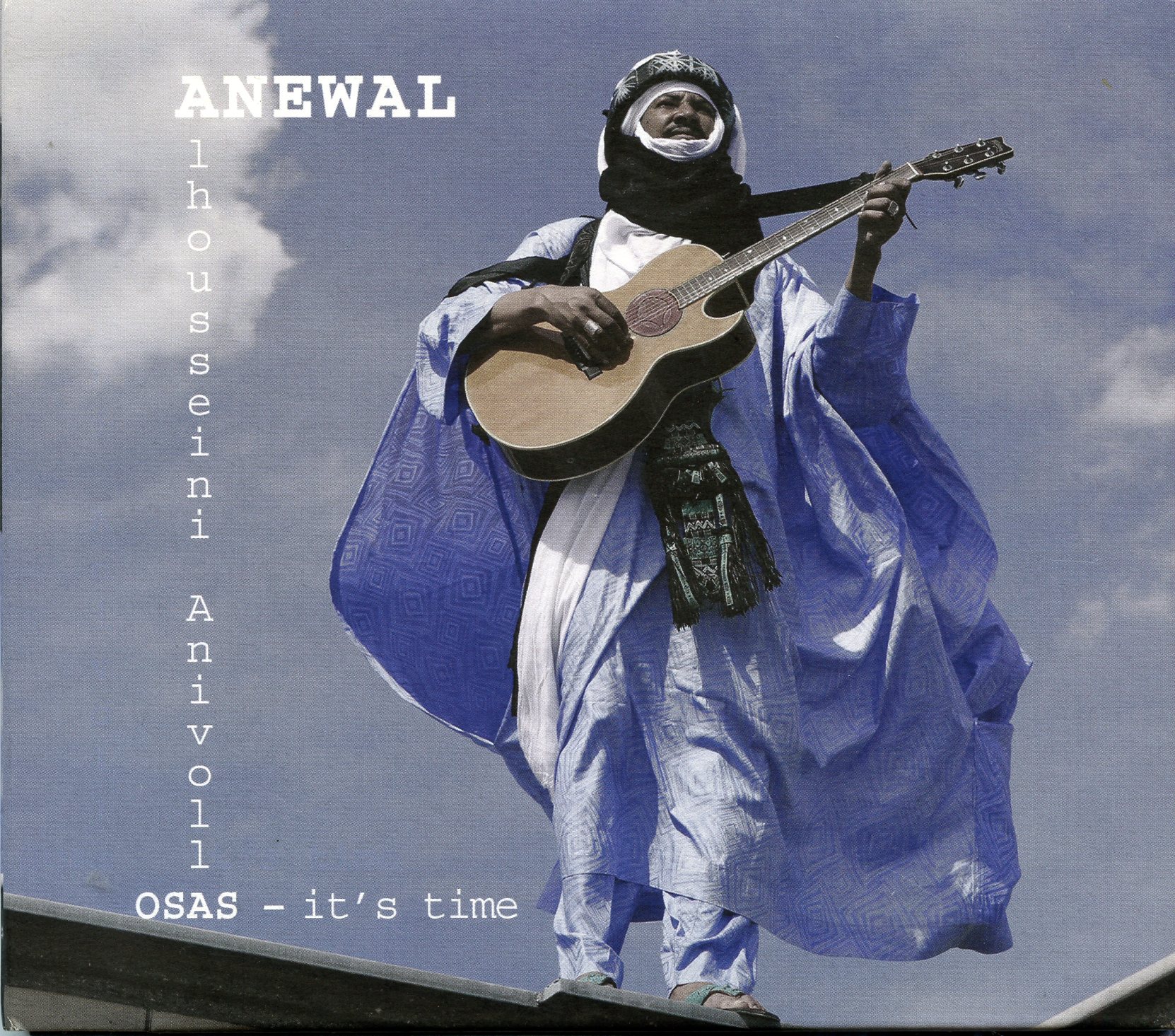

Alhousseini Anivolla first came to us with the Niger-based Tuareg guitar band Etran Finatawa. This, his second solo album, was recorded in North Wales with producer/bass player Colin Bass, a veteran of many fine global music projects over the years. Bass guitar aside, Anivolla plays and sings everything here, creating the illusion of a finely tuned, highly disciplined combo. The result is elegant blends of acoustic and electric guitars, often three at once, hand percussion and Anivolla’s deep, grainy voice commanding center stage, mostly alone, with hypnotic, chant-like melodies.

The sparseness of the soundscape creates a sense of ease and levity, but the subjects Anivolla sings about are profound. Preoccupation with the Tuareg people’s woes, especially since the messy rebellion of 2012-13 in northern Mali, is ever present. The CD notes observe that 400,000 people remain in refugee camps in the aftermath of that still simmering conflict. But these are not political songs. They call for something at once deeper and more practical than “independence.” The recurring theme is that people have forgotten or lost their identity and culture, and need to unify to overcome divisive quarrels. These are themes you might hear from any number of other Tuareg bands—Tinariwen, Tamikrest, Terakaft—but the difference here is that the perspective feels personal. These are ruminations, not of a clan or a band, but of one person, a wanderer, a nomad, a “walking man,” as Anivolla titled his first solo album.

Rarely have such weighty expressions of desperation, frustration and anger felt so gentle. The opener “Tamejaradetin” plays as ambling acoustic guitar folk, with a plea that people “speak the truth…honest as the morning light.” Picking up the pace and thickening the sound with clean electric guitar melodies, “Chet Azawad” namechecks the desert region that was briefly the name of an independent territory in northern Mali. But the words here don’t express an aspiration to reclaim Azawad as a nation, rather the pain and confusion that prevails in its place today. “Osas (It’s Time)” rolls in 12/8 time and a minor key with Anivolla almost speaking as he calls for peace and “laws to protect us.”

There are wistful notes of regret and reflection as in the slow, meditative “Idinite,” which questions whether “we” might have “ourselves to blame for what we are experiencing.” The energetic closer “Toumast Enkere,” with its tinde drum and calabash drive and its long concluding guitar jam, goes further with a scold to people who are “gullible” and “blind,” allowing themselves to be lured into conflict and division.

Recording without a band from the remove of a studio in the U.K., Anivolla might risk too much distance from his subject. But solitude seems to focus him. After all, separation is the central fact of nomadism. In the end, this album succeeds because the artist has such a deep need to say what’s on his mind, and knows exactly how to do it, without any need of artifice or reinvention.