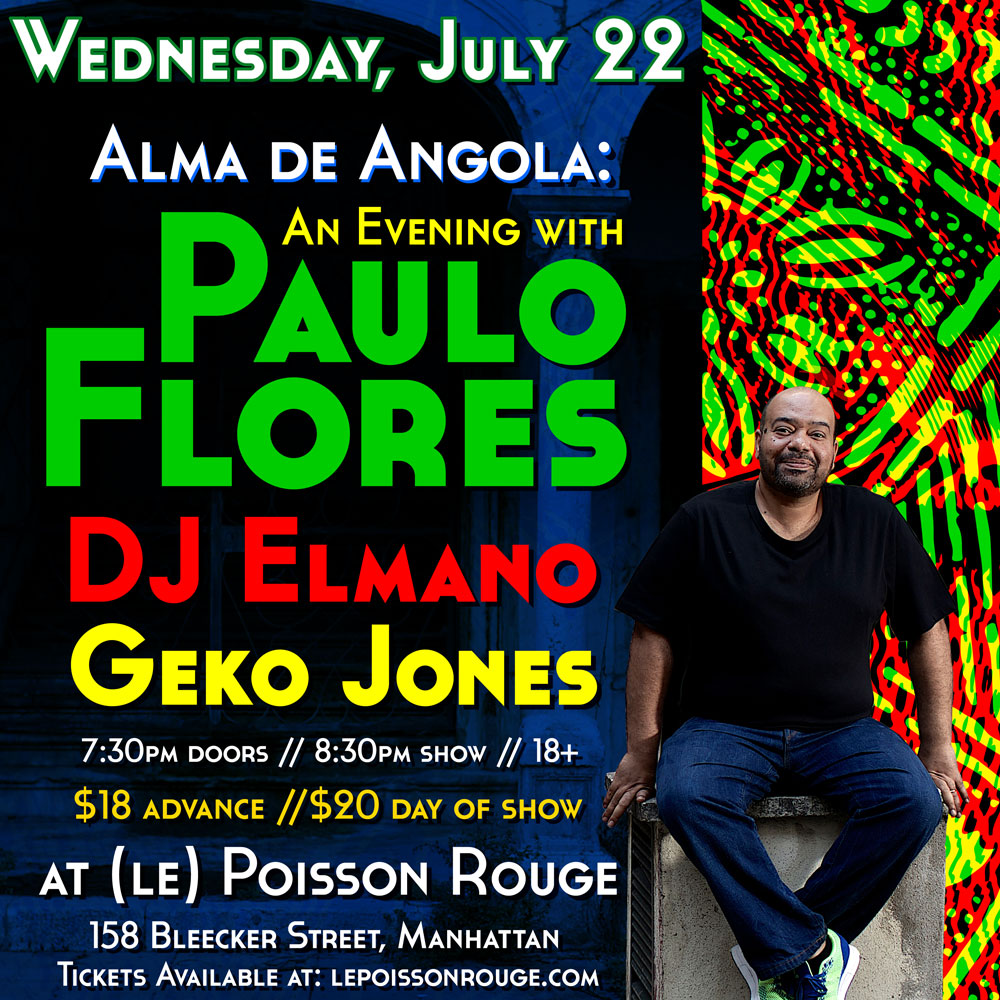

Paulo Flores of Angola may not be a household name in African music circles, but he should be. This singer/songwriter/bandleader first raised eyebrows in Luanda in 1988 when he recorded a solo album at age 16 at Radio National de Angola. Moving between Lisbon and Luanda in subsequent years, he became both the chief revivalist of Angola’s great dance sound of the 1960s and ‘70s—semba—as well as a key architect of kizomba, a newer dance style that has swept the Lusophone world in recent decades. Paulo performed his U.S. debut concert at New York’s Le Poisson Rouge on July 22, 2015. Afropop’s Banning Eyre, Sean Barlow and Ned Sublette were all there. Here’s their conversation with Paulo just before he went on the stage. Sean and Ned began by recounting Afropop’s work in Angola in 2005 and 2013. Questions from Banning, unless otherwise indicated.

Sean Barlow: There's not a lot of information about Angola in this country.

Paulo Flores: Yeah, but even on the Internet, we are still have very little information there. That’s something that I want to develop also, especially the memory of semba. I'm trying to get some guys to help me to create like a virtual museum of semba with all the information we can get. But we are just starting that process.

Banning Eyre: Well, good luck with that. For our readers and listeners who don’t know you, introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about your childhood and how you got into music in the first place.

I am Paulo Flores. I am 43 years old. I recorded my first album at 16 on Radio National in Angola. When I was a kid, I was really in between Lisbon and Luanda. My mother and my grandmother and my aunt and my great aunt, we went to Lisbon after independence, and my father stayed in Luanda. So I would always fly back for summer school vacations to Luanda. That was my first inspiration, my first school, the first things that really touched me a lot. I remember the first time I went back, I was sleeping in my father's bed. Because at that point, my grandmother in Portugal, she always said to me, “Don't go back to Luanda. Because if you go back, they will kill you. They are in war. Please don't go."

And I was like 7 years old. So when I went back to Angola, I was really afraid, so I asked my father to sleep in his bed. And I woke up the first night that I was there, and my father wasn't in the bed, so I went to the balcony on the second floor, and I looked in the street, and I saw a big black guy with no shirt, with ropes on his hands, and a military guy with whipping his back. I started to cry, and everyone stopped and looked at me. Even the guy who was whipping; I guess he stopped for a minute. Then my father comes up and tells me, "Don't worry. This is a thief that we got." So at 7 years old, my first night in Luanda, I understood that they spank thieves on the streets to make an example. So those kinds of childhood memories were very strong for me.

In 1979, I got back to Luanda again, and it was the year that Agostinho Neto, the first president, died, and we had like 45 days of mourning. I was a kid, and again, I was like, "What is going on?" And my father was playing some cards with his friends, and we were listening to a Muddy Waters record. But we had to listen to that at very low volume, and for the first time, I understood that we were doing something wrong, and that was listening to music. So all those kinds of paradoxes really touched me a lot. And I guess until today, my music has a lot to do with those memories.

Paulo Flores at Le Poisson Rouge (Eyre 2015)

Such contradictions. Yes, that's very interesting. What do you remember about the music you heard in Angola? You made your first record of 16. What was the music that inspired you?

Well, my father was a DJ at that point. And he had a lot of friends who were pilots, for area transportation to Angola. They went to New York, to Brazil, and they always brought records to my father. So when I was a kid, I was always singing over the albums. I can sing over Tom Jobim, Anita Baker, Al Jarreau. Jackson Five, Cuban music, Congo music. That was really my first school of music. I listened to everything. And when I got back to Lisbon, my grandmother and my great aunt, they always listened to the sembas and the classic music in Kimbundu, the language that they spoke at home. And afterwards, when I started to play semba, I remembered those songs that my grandmother and great aunt used to sing to me. And some of them, I got to record on my albums.

So it was really everything that I listened to. I do not remember that there was any kind of music we didn't listen to. We heard music from all around the world. When I made the first album, I knew only two keys, A and E. I did two records in those keys. Well, people liked it so… But I am like an autodidact. I never went to school of music. I guess in Angola, very few people did. Normally, the father passes to the son, the uncle passes to the nephew, and that's the way we deal with our tradition and passing through the generations.

When you made that first record in 1988 was semba still happening? Tell us a little bit about semba. What is it? Is it an old music? Is it traditional music?

No. But for us, we have had now 40 years of independence, so we are still learning how to walk. And semba was born really in the '50s, in the late '50s. So for us, it's a little bit old, but it's not a very old genre.

In the '50s, there was a band called Ngola Ritmos, and they remixed ethnic percussion instruments from semba, and started to transpose harmonies to acoustic guitar. And they were the first group that started to do the semba as we know it today. After that, in the '60s and '70s, we had groups like Jovens do Prenda, Os Kiezos, Tony de Fumo.

And we had two guys. Carlitos Viera Dias: He plays the guitar, but at the same time, he was like the biggest producer of Valentim Carvalho and CDA [Companhia de Discos de Angola]. That was the big record label at that point. He was the producer of like 90 percent of the music that came out at that time: Teta Lando, the Conjunto Merengues, Semba Tropical. And he was the son of Liceu Viera Dias from the Ngola Ritmos. That was the first guy that transposed the mokindo.

What’s that?

The mokindo, it's like a snare, but in wood. And it has a special clavé, and they transposed that to the acoustic guitar. From there, we started to play in that rhythm. And the other guy, besides Carlitos Viera Dias, that I think is really important in semba, is Joãozinho Morgado. Joãozinho Morgado is a percussion player. He played the congas especially. And he was the son of Mestre Geraldo. Mestre Geraldo was a guy who played the accordion, and played the masemba, and the masemba is really the origin of semba. It's a little bit mixed. Like when the Dutch were in Angola, they left us the accordion. And we have a dance that looks like a medieval European dance. That is, the men dress up in a tie and suit, and the women dress as bessanganas. It's like our traditional style. They stood with their arms together, around in a circle. And then, on the strong beat, they connect the bellies. So this is really the beginning of what we now call semba.

What year we talking about now?

We are talking about the father of Joãozinho Morgado, so that’s in the ‘50s also. In the ‘60s, the late ‘60s, Joãozinho would start to play the congas. And he and Carlitos Viera Dias, they played on almost all the records that we released at that point. So his father was Mestre Geraldo, and his mother was a washerwoman. And in the afternoon, she puts the clothesline out, and she turn it back, and sang in Kibundu. She created songs. So these two for me are probably the guys that made the semba happen.

Let's talk about these words: Semba and massemba.

Massemba, I guess it means that bellies getting together. You see? The woman and the man are with their arms together and then they look to each other and bang! Belly to belly. On the strong beat. That is the dance. I don't know. Probably even in Brazil when they dance around the fire, they called also that belly name. They called it umbigada. So semba, massemba, it means getting the bellies together.

Paulo Flores at Le Poisson Rouge

Paulo Flores at Le Poisson Rouge

Belly to belly. Very nice. So when you made your record in 1988, and you started your career, from what I was understanding, from Marissa Moorman, semba was going out of fashion, right?

At that point, it was just the memories of my great aunt singing to me those old songs. Because we were in a civil war, and in Luanda and Angola, nobody was recording. Only on Radio National do Angola, we had some tapes, old tapes in the studio and we could do some recording. And I was living in Lisbon. It's interesting, because I went Luanda to record my first album, and then I finished it in Lisbon. But in Luanda, nobody was recording at that point. So semba, from like from ‘77 until probably ‘94, nobody was doing it.

And I remember, I released my first semba album called Canta Meu Semba, and old singers from semba were saying to me, "Don't do that, man. Nobody will listen to that. Nobody is doing that again." And I said, "Man, I gotta do this.” And it was the way that I started in semba. And then I had the privilege of playing with Carlitos Viera Dias and Joãozinho Morgado and all those great musicians from the ‘70s.

Now that was after 1994.

Well, I started with Carlitos in ’92. Then I met Joãozinho. Then I went to live in Luanda for 12 years, and I met Banda Maravilha, and Bota Trinidade, the great musicians from semba, and I try to learn all I can about the genre.

Now you say you got songs mostly from listing to your great aunt and your grandmother sing. But why were you so attracted to that music when you're trying to be a new singer breaking out onto the scene?

Because I felt nobody was doing it. I felt that probably it could disappear if nobody recorded at that point. But after that, I started to feel like I knew my own voice in that genre. I can sing other genres, but when I sing the semba, I feel like I am really myself. And that's what gave me the idea of doing more semba. The sound that they produced in the ‘70s, until now, it's really the great sound that we have in Angola. The guitars, the way they could absorb everything. I said just a minute before that at that point you had guys playing congas, rock 'n' roll on congas. They listened to the records and they tried to do with our own sonority, with our instruments, with ethnic instruments. And I feel it was really a golden age for our music. And that's what I'm trying to revive also. The old semba.

Ned Sublette: Paulo, tell us about kizomba! More specifically, you with Eduardo Paim and Ruca Van Dunem--very creative people who are still doing great things-- what was it like, the personal dynamics of creating this music together with your various personalities. Tell us the kizomba creation myth again.

When I went to record my first album, Carlos Ferreira was a writer, and he took me and my father to Luanda and he introduced me to Eduardo Paim. He was living in a musseque [shantytown] in Kasenda, and they were starting to develop that new musicality, inspired by zouk from the Antilles. But they had again, our instruments and our own base way of doing things.

Ruca Van Dunem was the guy who had the electronics. He had the keyboards, the drum machine. And then I had, I guess, the lyrics and the melodies. Because for me it was very easy at that point to write. I did songs in 10 minutes. I was singing words, writing, singing words, writing, and when I got to review, I didn't change anything. Now I change a lot, of course. But at that point it was really blossoming from inside of me. And Eduardo Paim was very important in the arrangement in the productions, the ideas. He is very important in the creation of kizomba.

After I released my two albums, Ruca and I went to the studio with Ricardo Abreu. And it was like a community that was living in Lisbon and creating together—especially with that nostalgia of wanting to go back to Luanda. And we started to talk about the parties we had, the first girlfriend, things that nobody talked about in our music. So I really think that people at that point really related very strongly to what we were creating.

Ned: Was Manhã de Domingo recorded in Lisbon? And were you part of it?

Yes, we made it together. The first song on the album is my song “Esparina.” Then you have “Manyana Domingo.” Today it's really a big classic, because the lyrics were very strong, talking about us.

Ned: They are amazing lyrics. They are free verse. They don't rhyme. There's no chorus. And it's a dance record!

Yeah, I cannot explain that.

Ned: It's one of my favorite records. What year did you make it?

It's ’90 or ‘91. And people say this is the beginning of kizomba, but I started in '88, because my first record was really a kizomba record, produced by Eduardo Paim. But they didn't release it that way. We went to the studio to record it, and they were playing what we called kizomba at that time in Luanda. Eduardo Paim has three or four kizombas as we know it today. We gave it the name kizomba because kizomba for us, it means in Kimbundu “party.” Celebration. So we started to use that phrase. I have a song that I will sing today also called “O Povo,” the people. And I'm always saying, "The people who dance kizomba,” and I talk about several things that only we do, but I never say who “we” are. I never say the Angolan people. I'm always saying that there's this big guy who dances kizomba and who believes in the big singing contest we had in the ‘80s. So I think the name came really from there, and because we started to use those sounds became a huge success, everyone started to call the music kizomba.

Sean: Speaking of your hits, pick some of them and tell us about them.

For me it's not easy. I cannot explain myself well in English, but I will try. What I feel is really that we were very fresh in the way we approached the messages. We could talk about everything. We were young people, and we felt that we could do whatever we want. We could talk about everything. The country was ours, and we were talking about hope, about freedom, about dance, sometimes the negative things that our society lives daily. But still with the hope and the generosity of the people always present in the texts that we created. So especially I feel that our great strength was the way that we could talk about ourselves with no restrictions. And always the love we had for the place, even when we were abroad.

There was a song that was written for Nebsi Sosa that was an ancient poet and painter, and that song said, "I am afraid that I have too much love for my land." And in the end we say, "If I have to die, I will die for her." And I remember the day that I went to record that song it was after the first elections in ‘92. I was at my house and I was seeing in the television that after the elections, they restarted the war. I was shocked at seeing all the fighting in the city of Luanda, and then we went to the studio and recorded that song. So it was really strong, very strong. And people received it and until today, even the guys that are doing the counterfeit records with their home systems, they put that song.

So that time when I, Ricardo Abreu, Ruca Van Dunem, and Simon Tumasini, Eduardo Paim--it's like a magical time for everybody. Because we were at war, we had much less than we have today. Today we can buy everything. Everybody eats. But at that point everybody ate the same butter, everybody ate the same tuna. And even when you are richer, you have the same. You see? And everybody knew each other. So the first girlfriend, the first friend, the first party, all that that we saying, I guess today it's really a magical moment for everybody.

So singing that song, even though the war was still on, you felt both optimistic and that you could sing whatever you wanted. Has that been true ever since? Can you sing whatever you want today?

Well, the problem is I guess with age, we change. I'm really afraid that the world has changed. Because today, when I write, I am always thinking, "OK, probably this is too much? Let me see again. Oh, man, I don't know." I'm thinking too much. You see? I guess that's a problem. But I always felt that I could sing, and I still sing today. I think, I think, I rewrite, but I put it out anyway. And I guess we have that opportunity of talking about ourselves. But still, we have a lot of problems about free expression, freedom of opinion and that's something we are still struggling with—trying to get those benefits, trying to change our society a little bit. Still, it's not easy for us to talk about ourselves today.

We have only a few of your records. But one of them is this wonderful three-CD set called Excombatantes, from 2002. Tell us about this one.

Yes, I did this record when I was living in Luanda, in Combatantes. It's a neighborhood. In the colonial time, the avenue was called Avenida dos Combatantes. And afterwards, they changed the name to Comandante Valodia, a military guy, a hero. So what I did was to call the neighborhood and the record Excombatantes, because at that point we were finished the war, in 2002. And it was the first record that I did really living in Angola. Because several times I sung and I did lyrics of things that I never lived. I only did them because of what I interpreted. And I tried to express it, but sometimes it wasn't my story. But at that point, I did this record with generator sound. Sometime I was doing music and the light goes out, the power goes out, and I have to connect my generator. So several tunes were I was done with humming sounds. I remember that is really a commercial big avenue, and I would open my window and look to the other buildings and see a Mona Lisa painting imitation in my neighbor's living room. And that inspired me a lot.

I tried to give several musicalities on this record. The first CD is called Viagem. It's the trip, the journey, and it has to do with a trip that I did in Africa, in central Africa. I went to Gabon, São Tomé, Equatorial Guinea, Central African Republic, Cameroon, Chad, Congo. And it was really for me the biggest experience of my life. It's like a linking within Africa. Everybody loves music. Everybody hates the governments of their countries, and everybody is living with no dignity. You see? And Central Africa, you had the rebels 100 kilometers from where we were, and you had French troops all over the city. In the museums, they don't have pieces of arts. The schools don’t have teachers. Nothing. The only thing that I saw being built was a big church from Brazil. So I was 24 days doing that. It was really a great experience. That was the first CD—that trip and that musicality, even from Ali Farka Toure, from guys from Africa who inspired me.

The second album is the sembas, but not the conventional ones. I put strings on some of them. I did some more experimental sembas, even with dissonance and different chords. And the third one I did is about islands, Ilhas. Here, I was doing the musicality of the Antilles, Cape Verde, Isla de Luanda. So that was the idea, to have three different approaches to my music.

And then I have this CD called Semba, a collection of more recent songs. Maybe you could just pick a few of them and tell us a little bit about them.

Well, “Ngushi,” it's a classic semba, written by a woman, one of the biggest composers of Angola called Rosita Palma. And it was sung in the ‘70s by her sister, Belita Palma, again from Ngola Ritmos. I did it here with the kitushi, that percussion ethnic group. It's very interesting the sound that we made here. Then we have “Poema do Semba,” that is another big classic from our music. That is a song where I compare the genre with the people, and the way that genre survives, and the way the people are surviving. So I invited Carlos Burity, who is probably the biggest semba singer, to sing this with me. Because since the ‘60s up until today, there was never a decade where he didn't have a number-one hit in Angola. He is really the guy who sings the kimbundu and knows all the secrets.

I have here also “Belina,” a song from Arturo Nunes, another great composer who died at 27 years old. The song is about a woman that disappears in the war times in the guy that loves her is asking everybody in the neighborhood if they saw her. See, you have your several classics from Angola and other songs.

What about “Xe Povo”?

That's a song that was on the album before Excombatantes. After I tried to do the semba, I tried to do other musicalities. And Xe Povo is probably my most experimental record. I don't know how to classify it. I was free. And I had the producer from Brazil, Chico Neves. I had Jacques Morelenbaum again from Brazil. I went there to record with Brazilian guys, and the basis I did in Luanda. So it was the first album that I did creatively, freely.

Sean: Do the young generation, 20- and 30-year-olds, like and dance semba?

Yeah, of course. Today, kuduru is is bigger. The young kids are really doing the kuduro. But kuduru is the electronic way of doing semba, because the metrics of kuduro has to be with semba and kazakuta. But especially it has to do with the dance. And young kids love to dance, and the guy who gets more stupid, it's the best—but in a good way—stupid in the way that they invent new steps. You never expect what they will do next. But still, they are interested and they dance kizomba. Kizomba is very strong with several artists like Anselmo Ralph and C4 Pedro, young guys to have a different language, but still they are making kizomba go ahead. There’s a different kizomba evolution now.

And semba, everybody always will go and listen to semba on the weekend, with the family. People put the old songs and sing at lunches. So it's always present, also. What we need to do, and it's my worry now, it's how to teach the young musicians the secrets of semba, the cadences, the way the right hand works. All of that, we still have to pass it to young people.

We have to stop now. It’s almost show time. But thank you so much for this.

Thank you.