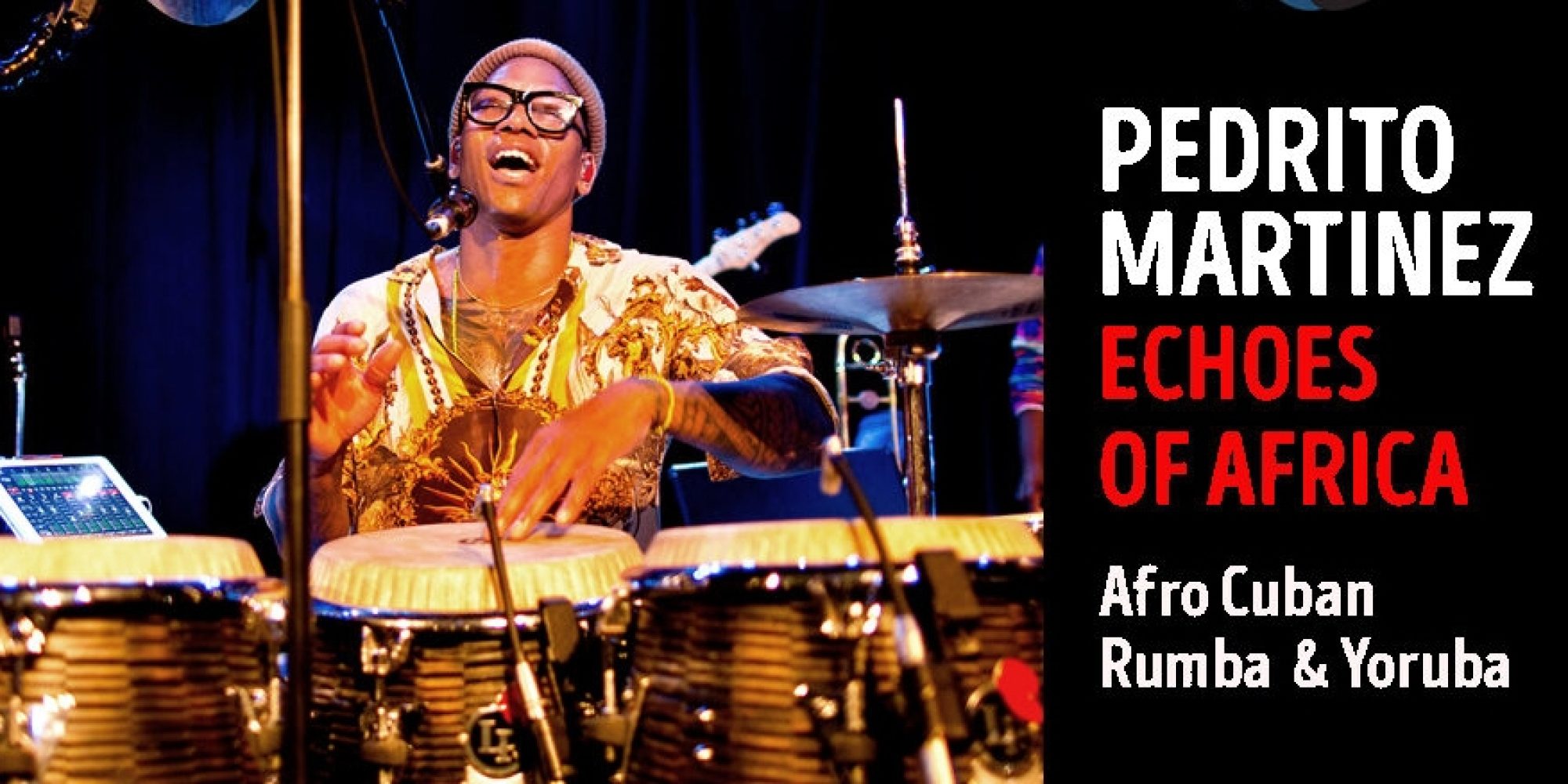

Cuban percussion maestro/composer/bandleader Pedrito Martinez has been lighting up New York venues with riveting performance for years. He kicks off 2023 with Echoes of Africa at Drom in New York on Sunday, January 15. The show incorporates elements of Afro-Cubanrumba and Yoruba roots, the two traditions from which his music springs, including percussion, singing and dance. Pedrito is widely regarded as the world’s leading percussionist in Afro-Cuban music and a vocalist of enormous talent. Leading his own quintet, he presents a high energy blend of Cuban timba, traditional rumba, and the sacred sounds of Yoruba religion, in which Pedrito is a babalawo. He spoke with Ned Sublette about the show. Here’s their conversation.

Photos by Soloman Howard.

Ned Sublette: What is Echoes of Africa, Pedrito?

Pedrito Martinez: Echoes of Africa, brother, is a project that I put together to continue developing the legacy of our ancestors and to continue promoting the Afro-Cuban culture all over the world, especially in my compositions, and especially in New York City, where I live. So this is a project where I’ve been adding to my songs more of the Yoruba chants, of the rumba culture from Cuba, and all the elements that I’ve been trying to make sure that people digest it correctly, or understand the purpose of trying to continue keeping alive the Afro-Cuban music.

Now, the Yoruba music that you play is a ceremonial music that allows humans to communicate with the divine. Rumba is a street-corner party music. How do you see these two musics as combining? How do they fit together in your work?

The rumba genre and the Yoruba, in my particular world, they’re both attached. It’s so well related, since I grew up listening to both of the genres. All these years a lot of rumberos, including me, have been adding a lot of the Yoruba chants into the rumba. That’s essential for me. You know, most of my compositions are related to the spirituality that Yoruba music brings to the whole world. They’re so well-connected, one to the other. It’s a way to express happiness, and you know, it’s so powerful for me, bro.

Does the way Yoruba music is played change stylistically over time?

Yeah! Through the years I saw already a big transformation in terms of the way the young generation interpreting how the batá sounds. Melodies have been modified a little bit through the years. I think it is essential to keep the way our ancestors used to play and sing all the Yoruba melodies and now [that] the new generation’s trying to add new sounds, it’s so important to keep the chants the same way they used to play [them]. That’s the only way we’re going to keep it alive. Nowadays the rumba people incorporate a lot of Yoruba chants. I think by now it feels for a lot of people that that’s almost something to put in the same genre. The rumba people add palo, abakuá, Yoruba chants, so you know it’s part of the whole – it’s the same plate.

In Cuba the rumba has continued changing. You have groups that have changed up the tempo, that are playing differently. Now that you’re a mature musician in mid-career, where do you locate yourself in the modern world of rumba?

I mean, you know, I’ve been checking all these new rumba groups. Still my favorite is Los Muñequitos de Matanzas.

Vaya!

Muñequitos are the kings of the rumba. They still continue keeping that powerful sound through the years. And there’s a lot of groups that I love. I’m not from Matanzas, I’m from Havana, so I’m never going to devalue or say something wrong about the rumba from Havana. It’s just a different way to interpret the rumba, a different formula and combination.

Yoruba Andabo is still active. Rumberos de Cuba, still active. Osain del Monte, Clave y Guaguancó, Timbalaye – I mean, they’re great. It’s just my particular opinion and my taste, you know, I still think the Muñequitos de Matanzas represent the original sound of rumba.

I think sometimes the new groups are playing too much, they are adding too much. Sometimes I don’t understand what they’re playing – if it’s rumba, if it's reggaetón, if it’s -- I don’t know what it is, if it’s a comparsa . . . You can add things to something, but you have to make sure that you’re not destroying something that was already great trying to create something new.

You know, people used to spend years trying to put together a formula and a great sound that works. It’s so important to make sure that we carefully continue keeping that powerful sound. I know everything’s subject to changes over the years, and I’m someone that’s always trying to make changes in my compositions and in the way I play, but I’m never gonna avoid the originality of a genre. I’m trying to keep the rumba, the batá, in a way that the old school are gonna accept it and understand it, and the new school too, you know? It’s a combination. We need to balance.

The Yoruba religion is a global religion now, with Cuba as its platform. Do you feel like as the religious music travels globally, it’s still something you can recognize everywhere?

Oh, definitely. But remember, depending on the society you’re living in, the environment you have, what country you live in, the interpretation’s gonna be a little better. It’s a way to accommodate and adapt the way you’re living and who you’re living with, who you’re learning from, to the society. The situation in Mexico is not the same as the United States. The situation in the United States is not the same as in Italy. There’s a lot of tamboreros in Italy. [And] all over the world! And you know, they’re trying to teach their students what they’ve learned. But what they’ve been learning all these years has continued getting changed and changed and changed, and it’s up to you to keep it the way it was, the way you learn it, and teach. And you show it to your students that way. If they want to modify things, it’s up to them, but they cannot say that you teach them like that. I have so many students that I saw videos of them playing on line, and sometimes I wonder, you know, I say to myself, that was not what I was teaching them. But that means that they learn in a way, and then they just interpret what they learn from you, in a way that’s comfortable for them.

What is happening in Mexico – there’s a lot of great tamboreros in Mexico, but their style is from the teacher living in Mexico, they’re gonna play the way people accept them in the society they live in. So I’m sure in Mexico, if a student plays in a ceremony something that they saw from me, maybe his teachers are going to say, “What is that? Where did you get that from? That’s wrong!” Or, “That’s great.” It can go both ways. It’s a great thing that batá is globalized the way it is. But the interpretation and the way people sing the melodies and play the batá, you see it different in Cuba, in New York, in Mexico, in Venezuela – there is a big Yoruba community in Venezuela. So it’s the same songs, the same dance, but they play it different.

You’ve been playing ceremonies ever since you arrived in the United States, and you’ve been in touch with a world of professional musicians that hardly anyone knows about who’s not really in touch with the religion, because there’s this whole world of highly professional drummers that play ceremonies, right?

Yep.

So you’ve had a really privileged position to see the inside of how this is working all over because of your prominence and visibility. How do you tune the musicians you work with into what you do?

In my group, the first question people ask me when they start playing with me, is, “Pedro, where do you get that powerful way to play the congas and sing and share with the audience? How do you keep your family tied together for so many years?” They relate my success as something they don’t know how to describe.

I always say, if you want to know where I get all this energy in life from, come to a tamborwith me. The first time I brought my group to a tambor de fundamento, they were shocked. They were like, “What is this?” They asked me so many questions, like why people salute the tambor. People leaning to the floor, put money into the jícara, why people go crazy with the tambor, and all that. And you know, metaphysically, there is an explanation, but there is a limitation to explain someone to feel something, you know, because everybody feels completely different.

Some people go to the tambor just to enjoy the music, some people go to the tambor just to find answers to their questions, some people go to the tambor to find the spirituality that’s gonna change their perspective on the way they live their life. So for me it’s a combination of everything, but the most important thing is the passion and the respect I have for the religion, which is what made my music different from other genres of music. It’s just so important for me that people understand that this is not just a religious music or a practice or a myth. This is a reality of a beautiful culture that has survived for so many years, brother, to have the knowledge passed from one generation to another. And when they understand that, and they absorb and try to grab pieces of whatever, they feel a changed perspective about music in general, not just religion. They start understanding what is music all about . . .

So, yeah, I bring people to tambores and they start saying, “Wow, Pedro, this is beautiful, this is powerful.” And then they start looking for that, they start searching. Because the most important is not just to learn from one source, you need to search and learn from different people, not just from me. I give you my experience, but you need to have your own experience. And that’s the way we sound like a group, because we all are searching. We are all targeting in the same direction.

Are you feeling energy from contemporary Africa these days?

Yes! One of my dreams would be to have on my album Salif Keita, Cheikh Lô, Baaba Maal, Oumou Sangaré...

When I recorded with Eric Clapton in his studio in London, I asked him, “Eric, I would like to know what music you listen to.” When I started listening to Eric Clapton’s playlist, it was all African music – music from Senegal, Mali, Cameroon, Ethiopia.

African musics still don’t have the value and the acceptation they need in the whole entire world. People know Africa is the mother of the rhythm and the music, but still, I would like to see an African category.

Nigeria, the home of the orishas, is a powerhouse right now. Nigerian pop music, Nigerian art, Nigerian movies and TV. Are you feeling any energy coming towards your work from that direction? I would love to see you play in Nigeria.

That would be one of my dreams. I’ve never been in Africa.

Africans are trying to make sure that people accept and understand and believe that whatever went to Cuba, Brazil and Latin America came from Africa. They’ve been putting a lot of information online about ceremonies, music, activities, about Yoruba religion.

I’ve been trying to see how I can connect more with people from Nigeria, and add more information to my music. I’ve been reading a lot. I’ve been trying to find sources of information about the classic Yoruba ceremonies, and even the vocabulary in the way that we transform so many words and histories. In Cuba -- because it’s a completely different country – we had to adapt so many things, and we don’t even have so many elements to continue doing things in our religion, we modified many things. And a lot of people have been trying to find the right source of information to make sure that what we’re singing in the ceremony, we’re doing that correct.

You know, I experience different things here every time I go to ceremonies. Because you see a mix, with people from Dominican Republic, Puerto Ricans, South Americans, Mexicans. You don’t see that in Cuba. You don’t see that in Mexico. This is one of the most cosmopolitan cities on the whole entire planet. It’s a great thing to see that here, how people canalize [channel], how people absorb, how people interpret the religion from different countries, living in the same country.

Absolutely.

Every time I go to a tambor I feel more powerful, I understand more things. And no matter how many years you’ve been in the religion, you’re always gonna be a learner, never a teacher. There’s so much to learn and there’s so many questions that still don’t have answers, for me. Especially a lot of the Yoruba chants that I learned when I was young. And I ask, what do they mean? Ninety percent of the persons I’ve been asking, they say, you know, this is an oral tradition, passed from one generation to another, and we don’t know exactly the translation, the meaning, we just feel. It’s all about feeling. I don’t agree with that, so I’m gonna continue trying to find the sources of information to answer all the questions I have still in my mind.

When I studied music composition, one of my composition teachers said to me, “A piece [of music] is an answer to a question.” And I’m thinking about that in terms of Echoes of Africa.

Yeah, you know, I’m trying to put together something that’s gonna make sense to people, that people feel so connected and attached to it. But you know, in the theoretical part, you need to be completely confident to answer the questions that your teachers never answered to you because they didn’t have the answer. It’s a big responsibility. And it’s a lot of time that you need to put on it, for people to understand, how do I describe Pedrito’s music?

You can put a million names to projects. But when you put a name on a project, you need to represent that name with your music, not just talking in an interview. If you are someone very eloquent, and speak very good English, or Spanish, whatever, maybe you can answer questions. But all those questions you answer, no matter how beautiful you talk, you need to represent those things in your performing. That’s the most important part. So you need to represent what you’re trying to sell in your show, and that’s the tricky part. Make sure that the musicians on the stage understand what you mean, what you want, what you feel, where you want to go, what you want to promote, what you’re expecting, what you’re gonna expect from people.

You never know what people are gonna think about when you start singing Yoruba. Every time I start singing Yoruba in “Compay Galletano,” I wonder, maybe someone who never heard this before is gonna come to me right after I finish and ask me, “What were you singing? What language were you singing?” And it would be embarrassing to tell that person, “I don’t know what I was singing but I learned it when I was 10 years old.” You know what I mean, brother?