On its surface, it would seem to be the simplest of issues. Yet the attempt to understand love has long been a trope- perhaps THE trope- in Western art, a shared obsession that has united everyone from pop-stars to playwrights. But even within the emotional turmoil that this search implies, we are still sure about what it is that we are confused about. Love. Self-evident, right?

The curators of The Progress of Love weren't so sure. The ambitious exhibit, which is being held in three museums across two continents, attempts to question preconceived ideas of love by engaging the specific set of conditions in which the dominant understandings of the emotion were originally generated. This awareness deepens and strengthens an understanding of a historically specific love, enabling a powerful exploration of how the narratives and conceptions of love that currently hold sway can be (and are being) reshaped by the communication technology and globalized culture that define so much of modern life.

According to most historical accounts, the modern conceptions of love mainly emerge out of the courtly life (and culture) of the high middle ages, specifically the romance-soaked song and poetry of the French troubadours. Obviously, some aspects of “love” existed long before that, and just as obviously, many have changed since. It is this process of flux that forms the exhibit's primary focus. According to Kristina Van Dyke, the former curator at the Menil Collection in Houston and the current director for the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts in St. Louis, the exhibit ultimately asks “What part of love is timeless and universal, and what part is culturally and historically specific?” In doing so, it engages with the art world’s longstanding role in creating these very paradigms. This awareness is present in the exhibition's very name, which it happens to share with a series of paintings by the noted French artist Jean-Honore Fragonard. These influential works depicted a powerful vision of romantic love at the moment of its widespread development and dissemination.

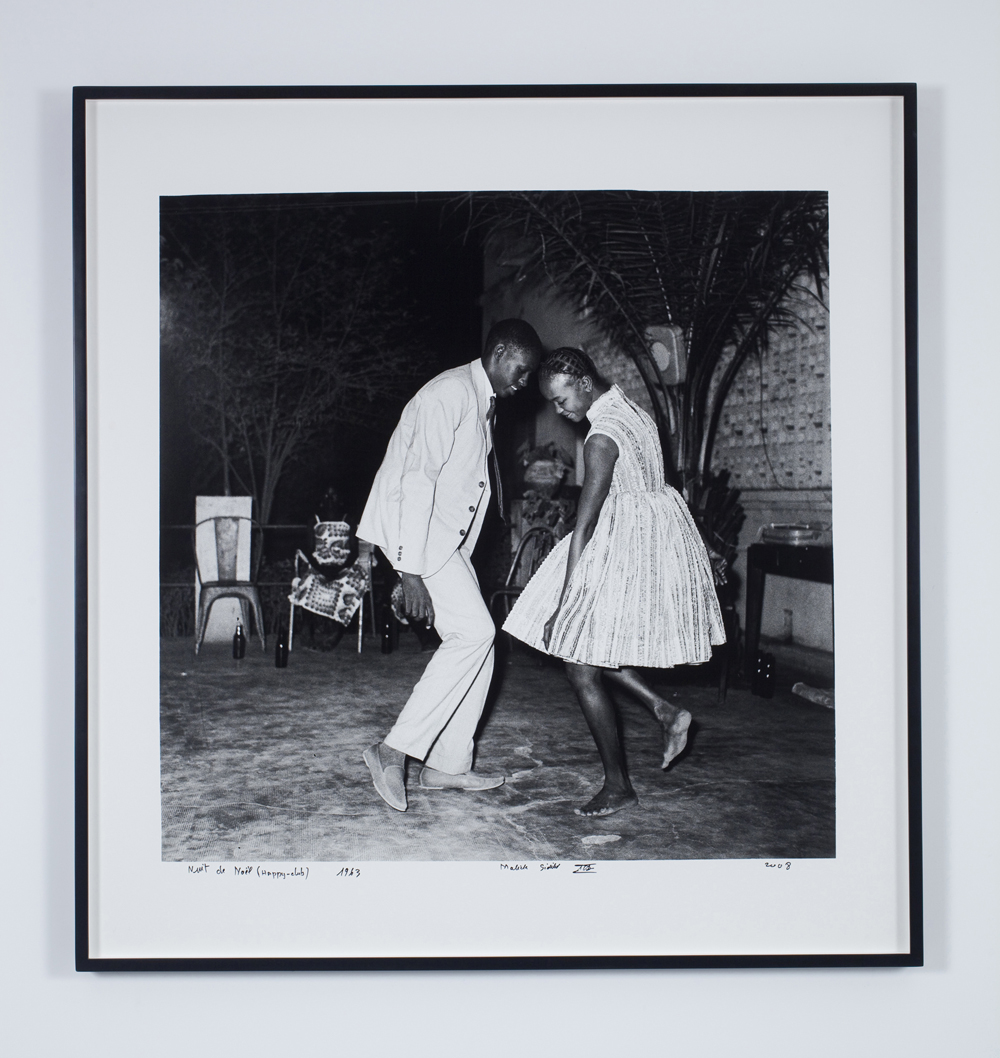

Kristina feels that this focus grew out of experiences that she had while doing fieldwork for her Ph.D in Mali. “As I got to know friends and colleagues there, a question that came up often in conversation on both sides was: What is love? How does love work in an American marriage? I was really interested in asking this question of my Malian friends and colleagues. As an American woman, I found myself struggling with the idea of polygamy and arranged marriage.”

To a great extent, the transformation from an inchoate interest into a sharply defined problematic was catalyzed by her engagement with the work of the British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonabare. Particularly influential was Shonabare’s “Garden of Love,” a sculptural instillation reacting to Fragonard's work by depicting headless European figures wearing luxurious period clothing made out of bright African fabrics. The argument is two-fold; both that the luxury which enabled European romantics was based on the surplus produced by a trade system intimately connected with the exploitation of Africa, and that Africa (and by extension, much of the “Third World”) still retains a complex fantasy relationship with Europe. According to Shonabare “The history of fabrics is in this way important….the Dutch who began producing these textiles at the end of the 19th century. Africans subsequently adopted the fabrics, thinking that wearing them would enable them to distinguish themselves from Europeans and emphasize the power of their culture, thus celebrating an African identity! Yet today we have now accepted the idea that these fabrics are actually “African”!"

The Progress of Love takes these ideas as a foundation, and then runs with them, exploring the experience of love from a variety of possible perspectives, perspectives based on the time, space and cultural position of the lover. In keeping with the idea that the experience of love differs based on the specific conditions in which it exists, each of the three museums has a differently named exhibit, with a different take on the issue. The curators, feeling that this would create a more powerful and conceptually fitting experience, choose this instead of the more common rout of pooling their resources to form a single unified show that would then travel between the museums.

Global Systems of Love, the exhibit at Houston’s Menil Collection focuses on the ways in which changing technology can transform love by altering the means by which lovers communicate. Texting is different than a phone call just as an email is different than a letter. In both cases, the means of communication altered the meaning of the communication, allowing for new narratives of love to be formed and others to fall by the wayside. According to Menil Director Josef Helfenstein, “our emotional lives have a history, just as our public affairs do - with similarities, differences, and cross-currents.”

Love As Mourning, the exhibit at St. Louis’s Pulitzer Foundation, focuses on the experience of love’s end. Just as the beginning of romantic love is surrounded by a set of assumptions and rituals, the ways in which an individual undergoes heartbreak is equally determined by his/her cultural position. The exhibit also goes beyond a focus on purely romantic love. As Kristina points out, the Progress of Love focuses on “all types of love- familial love, friendship, love of one’s past, love of one’s country.” This is therefore a radical form of historicism- an aesthetic questioning of the aesthetic means by which so many of our deepest beliefs are shaped.

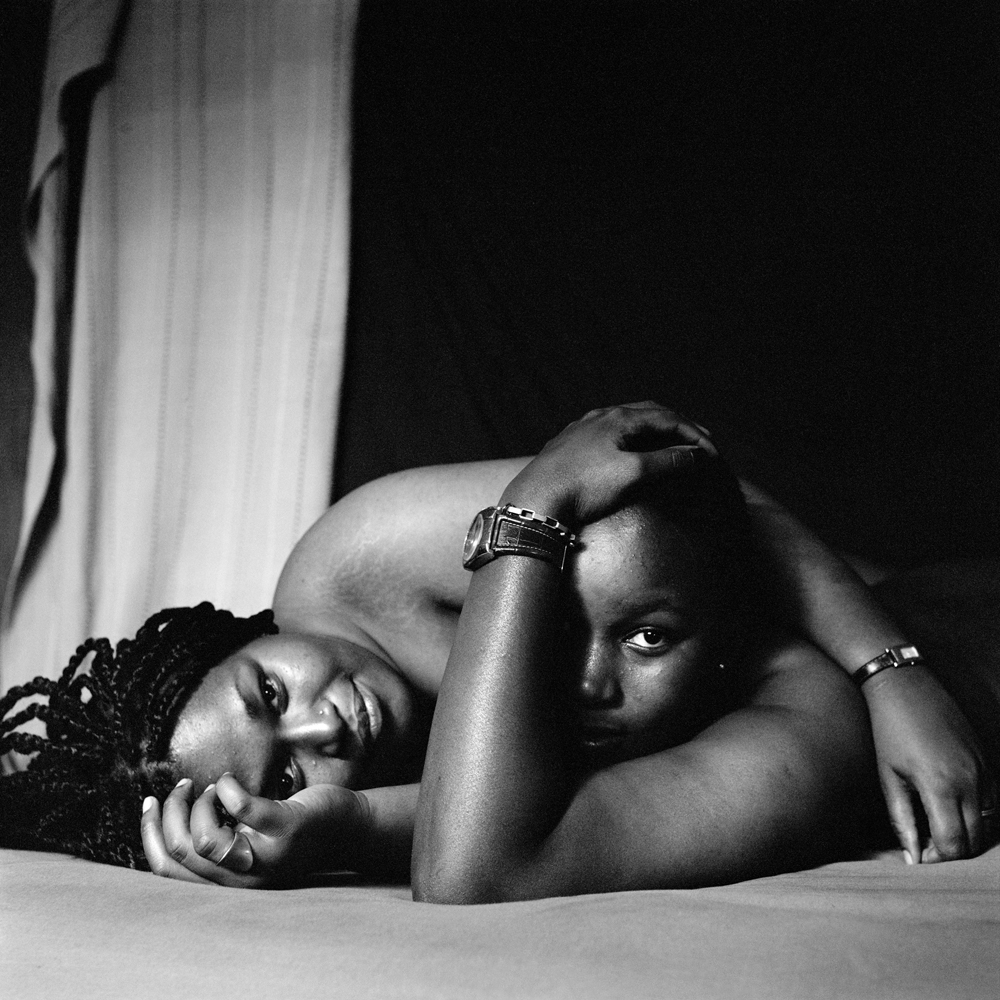

One of the most exciting things about the project has been the enormous role played by African and African Diaspora artists. Highlighting this is the (unfortunately rare) partnership of two prominent North American institutions with one based in Africa, specifically the Center for Contemporary Art in Lagos. The Center’s exhibit is named The Lived Experience of Love, and in keeping with that title, it focuses heavily on performance artists. Dealing with a particularly Nigerian (and more generally African) relationship to the idea of love, the exhibit explores how the emotion- construed in the broadest possible sense to include love of country, family, and community- can be both universal and local. This ability to redefine, and reconfigure a global love from within the sphere of the local is obviously powerful. In this case, it gains an additional charge from Africa’s historically complex relationship to the west, and the discourses (including those of love) that emerge from there.