Rab Bakari is one of a kind: producer, entrepreneur, DJ and artist agent. We first met during the research for Afropop’s 2013 Hip Deep in Ghana series. Rab had played a central role in the creation of the genre known as hiplife, a distinctly Ghanaian fusion of highlife and hip-hop. Rab’s mother was born in Ghana, but he grew up in New York City, coming of age during the birth years of hip-hop. As he memorably said in our first interview, “I came out of the late ‘70s, early ‘80s in New York. There were no community centers to teach me to play an instrument. But I knew about two turntables and a mixer, and spray paint.”

Rab admires innovation and creativity, and that’s why a few years back, he left his job at Universal, and began traveling to African cities, in search of artists he thought could help him to bring contemporary African music more deeply into America, especially African-American cultural life. So when it came time to assess the state of African music in 2016 for our program “African Music at the Crossroads,” he seemed the perfect person to look up. And he came through. Here’s an edited transcript of our conversation.

Banning Eyre: So, Rab, what have you been up to?

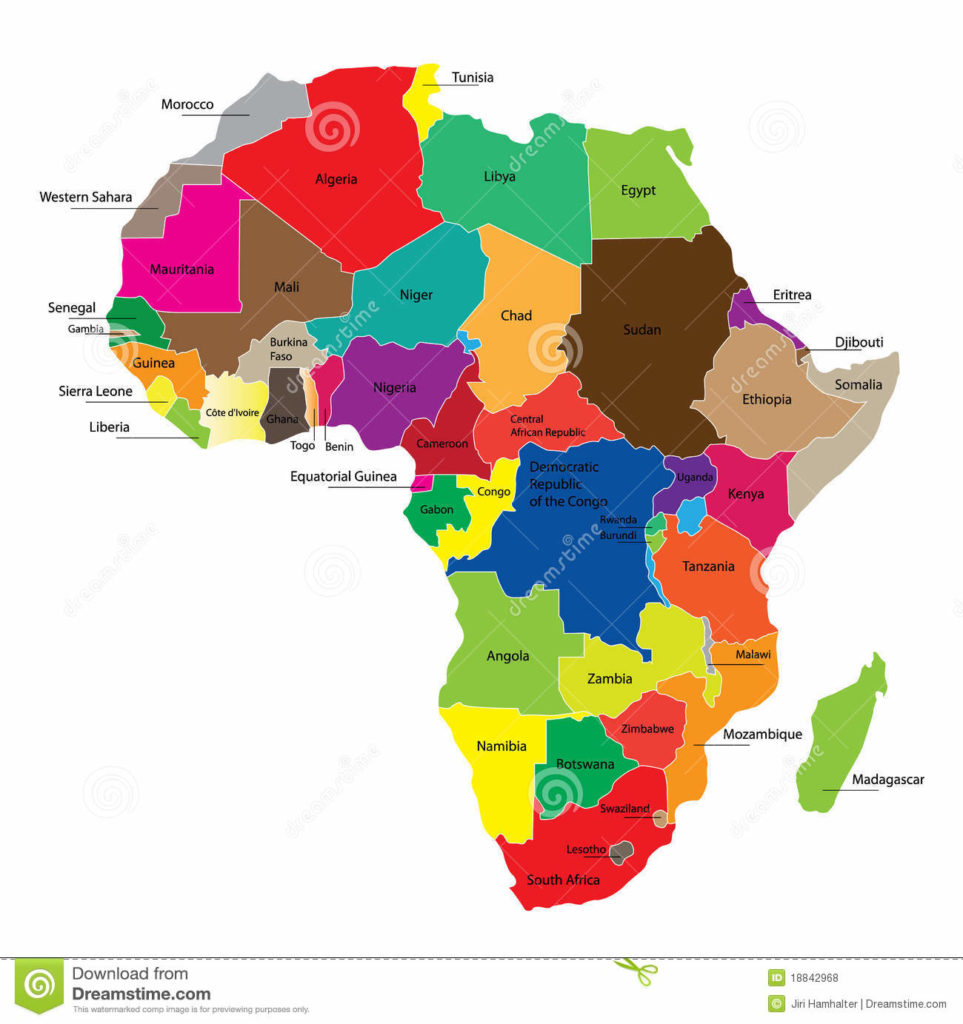

Rab Bakari: Trying to go back and see what's going on in urban areas, the metropolitan areas of the various African nations. I specifically deal with Accra, Ghana, Lagos, Nigeria, Tshwani and Johannesburg, South Africa, Luanda, Angola and Nairobi, Kenya. And each metropolitan area has certain forms of urban or modern music. They're taking influences from all over the North American continent, the South American continent, and within the African continent.

When we spoke in 2013, you talked about how the Francophone countries had been in touch with each other for a long time. They were exchanging artists. People touring from Mali and Senegal going to Ivory Coast, Guinea and so on. That had not been happening in the Anglophone countries, but it was starting to happen. What's the update three years later?

It's actually transcended colonial languages. Back in the ‘40s, ‘50s, ‘60s, ‘‘70s, and ‘‘80s, music on the African continent was broken up by whatever colonizer existed at the time. Those people only communicated with themselves. Cabo Verde talked to Sao Tome and Sao Tome talked to Angola, and Senegal talked to Mali, also to countries like Rwanda when they touted the French language.

Lusophone, Francophone and Anglophone–those were the categories.

Right. I’ll give you an example. In the Anglophone countries, specifically in West Africa, there was a commonality between what we consider highlife. So Sierra Leone had their version of highlife, Nigeria had their version of highlife, Ghana had its version of highlife. And to a certain extent, the mariners from the merchant marine in Liberia had their version of highlife. And they were all Anglophone countries.

But now, language doesn't group music at all. A lot of the modern musicians, whether they know how to play an instrument, or how to sing through auto pitch correction, or whatever, they are singing in their mother or father's tongue. And it's being played in other countries where people have no understanding of that particular African language. We used to talk about Francophone countries. You can’t even say that anymore. That's changed. And it has a lot to do with the American, specifically the African-American blueprint of what they call rhythm & blues, what they call rap, which I'll get lumped into this thing called Hip-Hop. That set a template for everyone to follow. That's what I believe, and empirically, that's what I know.

So less English and French.

Less English and French, yes. However, the Lusophone countries are still singing in Portuguese. I spoke to my friend from Mozambique, and you would think the southern African languages would be there, but he still singing in Portuguese. Even in pop music.

But in East and West Africa, a move away from English and French, toward urban local languages.

Right. And urban local languages can be a mixture of a local language with the European language. Like what they speak in Abidjan. That kind of French is a little different. It's a kind of pidgin. And of course, places like Dakar, they would rather sing or rap in Wolof instead of French. It’s definitely going more towards the local languages of the metropolitan areas. It's not pure. It's been mixed up with all kinds of stuff.

Interesting. The impression I had in Ghana, talking about this subject three years ago, was that there was no advantage to singing in English, because you had a bigger market. You could sell in all these other countries. And I remember back in the old days when we were first going to Africa, in the ‘80s, people always said that the reason people from Zimbabwe didn't know anything about music from Senegal was because of language. If they didn't understand it, they didn't want listen to it. And the one exception there was Congolese music, the ultimate dance music.

Right. They sang in Lingala, and they just transcended over the language.

But that was really the exception. Other kinds of local popular music were not listened to outside their language areas. So I had the impression a few years ago that this was driving people to perform at least partly in English, so they could be understood. Is that different now?

The attitudes have changed. It's totally different. And I'll give you an example. There's this rap artist who came on the Ghanaian scene first. He's from Tema, which is a sister city to Accra. It's about 30 km east of Accra. Sarkodie came on the scene, and he did not rap in English at all. All the guest appearances he made, he rapped in Asanti-Twi. Akan language.

Fast.

Fast, yes. And to this day in 2016, he hasn't changed that. And all his music plays in South Africa, in Zimbabwe, in Cameroon. He's done collaborations with Angolan artists, with Kenyan artists, with South African artists, Tanzanian and Moroccan artists, all over the place. And I'm sure those artists that he did collaborations with don't understand a word of the Akan language called Twi.

If you were to analyze why this change is happening now, is it a generational thing? Is it just part of Internet life, globalization, just a greater openness to hearing music and not caring if you don't understand half or all of the words? Is it really just a change in the way young people think about music worldwide? Is there a political agenda?

There is no political agenda, but there is definitely a change in how the young generation, meaning under 35, think about music, and want to claim it as their own. In the ‘80s, even the ‘60s, a lot of people left the African continent, whatever nation, whatever conflict or disruption in the economy caused people to leave. And it created these diaspora families in North America, Europe, Australia to the largest extent, and also other countries. And for some reason, people wanted to claim their own. So the more authentic the sound was, the more it was yours. So that rise from the diaspora, the Ghanaians living in Washington, D.C., the Somalis living in New York or St. Paul, the Liberians living in New York. All over. The diaspora outside, and then of course we know what happened in London, which I'm leading up to, this thing called Afropop and then Afrobeats.

It was the diaspora calling to say, "This is ours. We want to claim it. We don't want to be considered Jamaican. We don't want to be identified as Bajan, we don't want to be considered Panamanian. Or Dominican or Latino. This is our stuff.

O.K., but what about that kid in South Africa was listening to Sarkodie? He can't understand anything that's being said, so what is the appeal there?

So this is the thing. If you have a kid, and you want to be hip, and the rest of the world is saying Africa is one country, what they're saying is that Africa is not a country. It's diverse. So yes, Sarkodie can play in South Africa. He can do a collaboration with the South African artist, and his music can be played along right after a South African record, because the young producers that are using electronic music to make this music all started getting into this certain groove. And the only thing I can think of as a parallel to this is what happened in the ‘70s with funk. O.K., James Brown the godfather of funk, African-American, American, United States--you had countries from Benin, Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya trying to emulate that funk sound.

Our colleague Mark LeVine talks about "the funk belt," that whole stretch of countries that fell under this influence you’re talking about.

So fast-forward three or four decades. The rap scene in America has come of age. Rap music has become pop music in North America, so they're rapping in Spanish in Mexico, Canada is quasi-U.S. or whatever. So that groove is put out to the world again. So the kids are saying for us to be noticed and become popular, let’s follow the blueprint that was set in the United States. It's nothing different. It's been done before with the funk music. And the r&b, the rhythm & blues.

So could you say that the stylistic coming together across all these countries is becoming more important than the language?

It's definitely becoming more important than the language. And one of my good friends, DJ Edu, with BBC 1 Extra, “Destination Africa,” and we talk about how all the music is similar. At a party, you can play an Angolan record, and people don't understand Portuguese, and blend that same record, the BPMs, beats per minute, are the same and go straight into a Ghanaian record--and this was at the time when Ghana had a dance associated with the music called azonto.

Azonto. Is that kind of over now?

Yeah, they've moved on to something else since then. And then you go from that, you go to a Nigerian record that has traditional Naija rhythms, whether from the southwest or the southeast of the country--that blended right in with the Ghanaian record, and then from there you go straight into Côte d'Ivoire and get into their coupé decalé. It all just blends right in.

Now this has been bubbling and bubbling in for the last 10 years. So, 2005, 2006, to now 2015, 2016, it's been bubbling. Now, they all can do concerts together. They all can do shows together. And the persons consuming that won't even break a sweat, saying, "Oh, I don't know what this is. I can't jam to this." So you can go from Diamond Platnumz Tanzania to somebody from Ghana, to somebody from Nigeria like Davido, and then it's down to Angola.

And it has a lot to do with the beats per minute.

Yes. DJs play a huge role, but the unsung heroes in all this are the producers. Producers in the American sense, not the financier, but the one sitting in the studio programming. We need a guitar player who can play a certain kind of rhythm. They can’t play it themselves. So they get the guitar player. And they remember some drum patterns from some festival or something, and they re-create that electronically on Native Instruments, Machine Studio, Akai MPC, whatever, pads. Dump all the vocals into Pro Tools, and then you got something going.

So they are more apt to do it that way than by sampling old stuff, like we talked about last time.

Right. People like me, part of the whole hiplife movement Ghana, we did that. That sound was so incredible from back in the ‘70s from my mother's records that we had to go back and sample. So now they're recouping that sound electronically. And the thing is, in every metropolitan area, whether it's Luanda, Angola, Lagos, Nigeria, Accra, Ghana, Tshwani—which used to be called Pretoria—Johannesburg with the Afro-house, and Nairobi, Kenya experimenting with electronic and funk music and r&b music--they are creating their own sound by trying to re-create the old sound electronically. So everybody's doing the same thing.

At the right BPM. So can you give us the range? What's the sweet spot?

I'd say 125. 125, yeah.

Let's talk about Nigeria which now dominates African pop music. You once told me that in the mid-’90s, when you first went to Ghana, there was nothing really happening rap-wise in Nigeria.

No, there was not.

Naija pop star, Flavour

So this rise of Nigerian music is really something that has gone from zero to ruling the world in 20 years. How the hell did this happen?

It's the same thing that happened with South Africa abolishing apartheid, and now corporations are able to leave South Africa and start tele-companies like MTN. Military government ended in Nigeria later than in other places. There is a direct correlation of people being happy and under the thumb of oppression. Any oppressive regime holds things back. People are afraid to socialize. Remember the early days of Rawlings’ revolution in Ghana in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. They put in curfews and shut down all live bands. They effectively killed live music in Ghana, and Ghana had been touted as the live music place. People from South Africa, Zimbabwe, all migrated to Ghana to participate in the music. Hugh Masekela wanted to play his horn in Ghana. Fela wanted to hire Ghanaian musicians.

So the same thing happened in Nigeria. When Sani Abacha passed away… Sea change.

Yes. Change. Paradigm shift, maybe? People came back from living in New York and London, Toronto. People came out of the woodwork and of course, they bypassed the whole instruments thing and went straight to electronic equipment. To the chagrin of many. So you had music coming out like Ras Kimono, and then you had the whole fuji movement and stuff to try to counter the electronic revolution.

And those things are still happening I'm sure.

It's still happening, but it's like an underground thing right now. So the electronic thing--it was easy to go buy a beat machine and set up on your Windows or Mac computer, and compose. And that's what the producers did. They composed what was in their head, trying to re-create traditional sounds and they created various forms of Naija. There is no one Naija sound. They created various forms.

O.K., I have two questions. First, I'm wondering when people started lumping all the Nigerian stuff together and calling it Naija pop. Was that just a marketing thing, or was it something that happened organically among fans? And the other question is, why were the Nigerians so much better at it that they were able to establish such a dominance in the market?

This goes back. A lot of the key players in the Nigerian music business, and I've got the hand quotes up in the air, "music industry." They claim that they studied what was done in Ghana, so that means they were studying me and other people.

That's a familiar trope, isn't it? Things start in Ghana and become successful in Nigeria.

So they studied, and they took it to the level to the American standards. The reason why most artists in the United States went to record labels in the day, not so much now, but in the day--you pitch to them and say you have a business idea. "I can sing, and everybody will love me, I need financial backing." We used to call that a record deal. O.K., here’s $750,000. We are going to invest in you.

So the Nigerians took that mindset. Take plenty of money and put it behind one artist, and make that person bigger than Jesus. Dress them. Fake it till you make it. Put them in a mansion. It might even be a politician's mansion. And then those politicians or those businessman who have wealthy children that they sent to school, and they got influenced by American music, they just tap into their parents account to be what they want to be. They want to be a top DJ. They want to be the top… “Buy me the electronic equipment to produce. I'll become a rap star.” So it became a money thing. Ghana didn't have that much money.

A money thing. Nigeria had more money.

Money. I will make you a star. When you walk down the street, people will believe you’re a star, even if you came from humble beginnings. Your dress, your videos. They just took it to the next level finance-wise. If it cost him millions of dollars to get the hottest equipment imported from Europe and America, fine. If it costs $1 million to do the video. Got to rent this car for some big woolly guy for the day, and we got to use his mansion. That's what we have to do. And that's what they did, over and over again.

To this day, the formula is still the same. The male artist, the fancy car, the big house. You look at all the Nigerian music videos, it's the same. And then male dominance, and you bring in the girls. The girls are usually below them, dancing, complementing them, but not shining over them. So a star like Tiwa Savage is somewhat of an outlier in that paradigm, right?

Yeah. She's an outlier because she's a female, coming from the Yoruba people, but at the same time, she's using the same formula. O.K., what are the American women doing? Women over here are looked down on in society. Women over here are not elevated as a man is. But look at the women in the United States, specifically black American women when they sing and stuff. Mariah Carey or whatever. I need to be on that level, coming from left field. So what if they criticize that I'm shaking and doing something sexual and sensual. That's what the Americans are doing. An outlier yes.

O.K., let me ask you about Naija pop. First of all, I've seen this word popping up in the literature and press just in the last few years. Where did it start? Who coined the term? And what does it really mean? Why do they spell Naija that way? I think it comes from pidgin. But just riff on Naija pop a moment.

O.K., Naija. N-A-I-J-A. Naija is slang for the country Nigeria. Every country has some type of slang, you know. People refer to the United States, they say Americans, or they could say Yankees. Yankees is kind of archaic, but you get the gist. So Naija is the slang, but that originated within Nigeria. That's not an outside person saying that. Because usually when an outside person calls someone something, it's derogatory.

When Nigerians started making music, they still call the music by the genres that you and I are familiar with, praising God, specifically praising Jesus, it's called gospel. If you’re talking about hope and lifting of the human race: inspirational music. Bob Marley set the pace in the late ‘60s, so there's this thing called reggae music. If you're toasting over a staccato beat, it's ragga, which is really from the Brits. In Jamaica, in America, they call it dancehall music. Rapping, making words rhyme, it's called rap. So Nigeria never really had a term for its music.

Well, they had highlife, juju and fuji…

I'm talking about the modern music. Because how many ethnicities are there Nigeria? It's not a homogenous country.

So one of the characteristics of this new music is that it is not ethnic, right?

It's not. So that means that a wedding in Jos, Plateau State, they can play some artist who grew up in the southwest in--pick a state –Ogun State, Yoruba Land. “Ah, he’s speaking Yoruba. Actually, he's rhyming and singing in a broken type of Yoruba. It's the slang of Lagos, because Lagos happens to be in the traditional Yoruba area. So everybody, no matter what part of Nigeria they come from, they're going to end up speaking some type of Yoruba sentence or something like that.

I think it had to be the media within Nigeria recently that branded the music as Naija pop. Because when they started exporting to countries like South Africa through satellite television, or DSTV, all these little networks like Sound City or Channel O, they had to give this Nigerian music some kind of generic brand name. Because if we just said Nigerian music, we'd be talking again about juju and whatever they're doing up in Kano—the Hausa people and the Fulani people have a whole different mindset of music and stuff—so they had to give it some generic name. That's a recent phenomenon.

How recent? When did you first start hearing that word?

I started hearing Naija pop when I went to Johannesburg and saw South Africans dancing to Nigerian music. They called it Naija pop.

How long ago was that?

Maybe 2012. But before that, the diaspora in the United Kingdom, specifically the DJs that started playing this music, started calling it Afrobeats, with an “s” on the end.

So this is DJs in London specifically.

Right. They never called it Afrobeats in Ghana or Nigeria. Never.

Do we know who first coined the term Afrobeats?

There's a debate between two London DJs, DJ Edu and DJ Abrantee. Edu, Edward Otieno, is a Kenyan. And Abrantee is Ghanaian. Abrantee means like a strong boy in Twi. They started doing mix tapes with Ghanaian music, and some Nigerian music, but then they started realizing that South African Afro-house, and Angolan kuduro and Angolan Afro-house also… Basically South Africa just about copied the Afro-house of Angola. DJ Edu started playing all of those together, along with the Ivoirian coupé decalé. Yes there was still ndombolo and soukous being made by the Congolese artists, but it didn't blend in with those.

Right. Those are clavé based. There’s a different rhythmic structure.

Right. It didn't blend in. That went by the wayside, what was coming out of Brazzaville, Brussels, Kinshasa.

So what year does this happen? A little earlier.

I'd say 2009. Hiplife was still going on, but then these pop beats started coming on. People could sing the hooks. And then a lot of artists stopped the rapping. Rappers started singing. But they were just mimicking what the Americans were doing, because American rappers started singing also. But often, they can't carry a tune. They can't follow the pitch. So you fire up your plug-in, throw that person a pitch. But some of them are so off you get that trill. You ever hear that trill?

Sure.

That's the Auto-Tune. If you can sing, you'll never hear that trill, because he will be in perfect pitch. Those who are forcing to sing, and then they started using the voice as an instrument. So everybody started doing it. Forget T-Pain and all that stuff, in America. T-Pain started around 2003, 2004, by the time Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, they started learning about it was many years later.

About five years later.

Yeah, about five years later. And that became the trademark. That branded as Afrobeats. You hear that, and you know it's the Afrobeats sound.

So it's a combination of the singing, the Auto-Tune, and being at this particular beats per minute level, so that you have this combination and move from country to country. That explains a lot.

Right. Then, the drum pattern. And every ethnic group has its own drum pattern, so you can imagine every nation has various ethnic groups. So how do you brand all that stuff? They’re singing in different languages, they’re playing different types of rhythms.

Different countries, different cultures, but you got to have some way to talk about it.

That's it, so I may ask him, "What are you playing?” They can't say I am playing Nigerian music, because Nigerian music is gospel, inspirational, jazz. I may go down the list. Rap music, whatever. So they call it Afrobeats.

So it comes in London, from DJs.

Right. Growing up here in New York, I never heard the term Afrobeats. We can go back to Fela: Afrobeat.

Of course. But I do wonder what those first DJs and that term were thinking. Because I asked a number of people at the Barclays Center event, “What does Afrobeat mean?” Someone say that it was paying homage to Fela.

[Laughs]. I don't buy that.

O.K., so they really weren't thinking about Afrobeat and Fela at all. They were just looking for a word that would work.

You see, in these metropolitan areas like Luanda and Johannesburg, Black Coffee and them, they call their music “house music,” and then they started putting Afro on it, Afro-house. Generic term, right? Renato from Luanda, and these guys go back and forth to Europe and stuff. In Ghana, we had azonto, and that was tied to a dance. So you have people like EL and Killbeats, who created the azonto sound. Before, Ghana had the jama sound, and before that, they had hiplife. So they had names, but what's all this music sounded similar, you could DJ and blend one into another.

So how do you talk about them all at once?

All at once. And so they just generically started calling it Afrobeats.

When we went to Ghana in 2013, nobody in Accra then seemed to be using that term.

Right.

But now they are? I had the impression at the One Africa Fest that this is now a word everybody uses. So it starts with DJs in London, but it has this kind of logic to it, because it simplifies the problem of all these different languages and quality patterns.

But doesn't it always happen like that? Rock 'n’ roll in the ‘50s. How do you call that type of music when different cities in the United States were playing it in different ways.

But some names last and some don't. I guess it's too early to say about either Naija pop or Afrobeats, because they're both so young. But I could really see a difference talking to artists at the Barclays Center, at the One Africa Music Fest, that they were all using the term Afrobeats, whereas a few years earlier in Ghana, they were not. So now it's becoming a genre.

Well, it's sort of a genre, but at least it's a commonly used term. People know what it means.

Yes, it's the modern, urban music. There's always an urban movement. People from the hinterland grab a guitar in the ‘60s, and the next thing you know, you got these polyrhythmic orchestras. So this is the modern, urban music of Africa. So you have kids in Douala, Cameroon, and kids in Yaounde, imitating that whole Afrobeats sound, totally disregarding the sound that they're supposed to be playing in those towns. Now Naija pop is a little bit different, because it has to be something that is danceable, and I can fit into a dance music mix.

You wouldn't think of Naija pop as being a subgenre within Afrobeats?

No.

How are they different?

You know, there’s a formula for pop music around the world. So Naija pop would follow that formula. Some silly, catchy phrase, you know.

So give me an example of the Naija pop artist or song that’s not Afrobeats.

Oh.

I’m putting you on the spot here.

That’s interesting. Because they’re going back and forth. As a matter fact, some of them that were doing Naija pop, and pure Afrobeats, like techno, then they’re doing dancehall. Or, they’re guesting on some rap record.

One of the people we asked about this said that Afrobeats can be anything. It can be dancehall. It can be rap. It can be r&b. Whatever. It just has to be the modern urban musical of Africa.

Well, Naija pop will be the pop formula, whatever is the pattern of music for the day. So pop in 1978 in America was disco. Pop in the early ‘80s was DX7 Yamaha keyboards and Debbie Gibson. Pop now, it has a lot of rap elements, swag and all that stuff. Justin Timberlake. All that stuff. Pop is the thing of the day. It has that formula that appeals to everyone. So a 5-year-old kid can dance to Naija pop and the 85-year-old grandmother can also dance to Naija pop.

I interviewed the Nigerian artist Lagbaja last year.

The saxophonist.

Yes, the guy who wears a mask. Interesting guy. He was telling us that there had been a big hit recently, I think it was by Davido, that changed the rhythm of the music. It was putting a 12/8 feel into it.

He’s probably talking about “Aye,” which means “life” in Yoruba.

Right. And he said that since then, a lot of people are following that lead and doing that.

Yes. I could find tons of them right now on my phone.

That’s interesting to me, because I really like 6/8 and 12/8 music. Because we don’t have that much of it in our pop music. But now there’s more of it happening in this modern music. You could see that as a factor of inserting more of an African identity in music that could otherwise be seen as more derivative.

It is a movement within Afrobeats. But Naija pop has to be able to convince a 22-year-old Copenhagen woman in Denmark to dance, and that’s what the whole focus of the Naija pop is. And then you crank up the BPM. BPM can go anywhere from 122 to 135. And getting with those dance records. That same formula. First, cheesy verse, then right over to a really corny, catchy repetitive chorus.

So I’m getting the feeling that you’re not all that impressed with Naija pop as a movement.

I’m not impressed with any type of pop music at all.

Oh really? So what are you digging these days?

Stuff that people you see are really trying to turn an instrument into something that it never did. That’s how bebop came in jazz. Someone playing the piano, you can play like Beethoven did, you can play different way.

I relate to that. That’s what I love about African guitar players. They’d play the instrument in ways that no one else would ever think of.

Or take a turntable, let it turn around 33 1/3, pull it back, and turn it into an instrument. That. I did stuff like that. Or if you’re doing electronic musician, what they call EDM, you’re tweaking that sine wave oscillation, filters, you really dig into it and take it and make it do something different.

Speaking about turntables and all that, I know that you came up in New York in the ‘70s. You talked about your childhood. I’m wondering if you seen this new Netflix show The Get Down.

Yes I have. You know, you could be an academic type person and say it should’ve been presented as a documentary. Or you could look at it as pure entertainment. They presented it as a combination between West Side Story, a Motown movie called The Last Dragon in 1985, with elements of Hip-Hop. You know. And they made Grandmaster Flash into a guru. That was quite interesting. Or Kool Herc as a peacemaker.

So I shouldn’t take it as gospel.

No.

But did you enjoy it?

I enjoyed it. Because me, growing up in New York City, I remember the Hip-Hop era. We didn’t even call it Hip-Hop then. That was a generic term that was slapped on later, when the rappers hit with, “Hip, hop, hippity hop...”

Now there’s a term that’s not going away.

Right. But probably Afrobeats isn’t going to go away either, because it just branded something. We called ourselves beat boys in the late ‘70s, or break boys. In this show they use the term “get down.” When you took the break, whether it was a bass break, a rhythm guitar break, drum break or conga break. You looped it by going back and forth with the two turntables and the mixer.

That’s’s when we would go down to the floor and break, but we didn’t call it that. We didn’t have a name for what it was. The media called it that. But I appreciate The Get Down because it captures the whole thing, interweaving Mayor Ed Koch, corrupt politicians, the burning of the Bronx, the graffiti on the subway trains. The juxtaposition between pop and disco. I’ve seen it all. I was there. The fashion of the disco people as opposed to the fashion with teenagers who later became the Hip-Hop heads, the boys. The immigrant community at the time, the Puerto Ricans who came into New York at the time.

It’s all very evocative.

It was very nostalgic for me to see that.

It’s really great to catch up with you and talk about these things. You know, we are inevitably perceived as old school, and in many ways we are. But it’s fascinating to see how quickly and profoundly popular music is changing. That’s why we’re going to Lagos next year to really take the pulse of Afrobeats and Naija pop at the epicenter.

Back to Lagos, the economy and infrastructure supports this entertainment industry. They really don’t need to go to London, Toronto, or New York, Washington, D.C. to record. If they’re doing it, it’s because there’s somebody over in those cities that they want to work with. They don’t really need to go to those cities. Everything is there.

There’s this impresario Paul Okoye, the man behind the One Africa Music Fest. He spoke from the stage about how this music was breaking in America, but the audience was all young African and Caribbean diaspora folks.

And you notice, it wasn’t a Nigerian thing. He said “This music.” He brought artists in Tanzania, Ghana, and Nigeria.

So clearly the music is reaching the big diaspora. The African/Caribbean diaspora in America now is more upwardly mobile and numerous and they were 15 or 20 years ago. It’s not just a little niche.

And the music is not exotic anymore. You remember the early ‘90s when Mali bands used to come and everything was exotic.

Yes. That’s the world I grew up in. Malians would come and look out at an all-white audience and say, “What the hell is this?” What we’re seeing now is very different. But as you say, these bands don’t have to come here. It’s just an interesting thing to do. I doubt anyone made a lot of money on that One Africa Fest. There were so many people to pay.

Yes. And it was not a big deal in the media in Africa that they performed here. Because they come and go all the time to perform. They perform for the Ghanaians who left Ghana when they were four years old, or the Nigerians who left [when they] were 10 years old. They come all the time. It’s just that the New York Times, the New York Post, the Village Voice, they don’t really write about these things. But these artists, all the time. There are three artists in town right now.

So there’s a big disconnect. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, when African acts started coming here in number, there were still record labels to support tours and promote. There was a whole sub-industry that developed around music you could generally described as Afropop.

So here’s where we’re going now. Specifically speaking about: has it arrived in North America? It’s the same thing with ska and reggae. It arrived for those who knew about it, but then, when the major labels--at the time they were the financiers--got to it, then it really arrived in America. So now, in the early ‘70’s, everyone knows reggae. Then later, in the ‘80s and ‘90s, it became dancehall. The sound systems were doing it in the dance halls in New York, Toronto, Kingston, Jamaica, London and the U.K. That became a popular thing, and then later the Latinos wanted their voice, so they borrowed from dancehall, that one rhythm, and they created reggaeton. So now everybody from Panama, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico. They’re all doing reggaeton.

So Afrobeats is the next logical thing for America. And I always tell people, when it gets to the black Americans, then that’s when it’s going to become a thing. So the black American at a barbecue in Atlanta plays Chris Brown, this young r&b artist. Then they moved to the Caribbean artists. So they have Sean Paul. Everybody knows Sean Paul. Regardless of his color, he is Jamaican. The next logical person that Universal or Sony wants that to be is Wizkid. So an African-American, who’s never been to Africa, and her name is Mrs. Jackson, she knows knows Chris Brown, Sean Paul and Wizkid, all in one barbecue sitting, and she’s dancing from one record to the next.

Is that happening yet?

Not yet. But when that happens, that’s when this thing we call Afrobeats—I’m not talking about Naija pop—Afrobeats will come to America. Not when it’s playing for the diaspora kid who came when he was 8 years old, went to high school here, went to college, and only went home back to Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya for Christmas or something.

And that’s who was at the Barclays Center.

Yes. When it plays for that African-American, that’s what makes it to America. Course when it becomes African-American, then all the African-American artists will do it, and the sample switch. The next thing you know you’ll hear Mary J. Blige and Ludicris doing Afrobeats.

Let’s talk about that barbecue scene. What’s it going to take?

Radio. Terrestrial radio. That’s it. When a person gets in the car and they hear the same song. And 25 minutes later, after they play the adverts and commercials, that song is there again. It beats in your brain. You don’t need to understand the Yoruba of Davido and Wizkid to hear it on whatever Hot or Kiss or Power or whatever.

O.K., so these African artists haven’t reached that barbecue yet. But it does seem like there’s a little bit of progress, hasn’t there?

Exactly. It’s a little bit. Because when I go out and hang out with some friends that have never been to an African metropolitan area, like one of the cities I’ve named. They are hearing about it. They don’t know what it is, but it’s actually quite specific. “That’s Nigerian music.” As opposed to it’s “African music.” Little by little. Like that.

So the process is happening, but like all these things, it’s not happening fast.

Unfortunately, these African metropolitan areas are going to move onto something else. The stuff we’re talking about now is already in its fifth year of popularity. It’s getting old. How long did disco last? Disco came out of the funk era. The transition between funk and… You can probably remember when bands that you love went disco. You can probably remember the day.

Oh yes. I was disappointed.

I’m talking about from rock bands. The Eagles to Isaac Hayes, James Brown.

The Bee Gees.

Everybody was doing disco. But how long did that last? Four years. Think about eras. How long was the break dance era? Four years?

And it moves even faster now.

Yes. So the whole branding of Afrobeats. Naija pop may always be there. It may become another genre of music along with Christian gospel and their variation of jazz, their fuji. But Afrobeats, with the whole branding, the sounds will change. It may get slower. The rhythms may come back down to 90.

But that’s what’s so brilliant about that name. It’s so nonspecific that the music can change and it will still be Afrobeats. And for that reason, it may be around for a while. So let’s talk about you. What’s going on with you these days?

Rab, at his desk at Universal

Since I’ve left Universal, almost three years ago now, my title is pretty much an agent. I take artists, specifically musical artists, although it can be other, and pair them with corporate partners. Because there is no such thing as a proper record label. Traditionally, you would go to a record label to finance your dream and your idea if you are a musician. These days, they go to corporations, whether it’s a telecom, whether it’s a beverage company, or an alcohol company, or tobacco company, or some manufacturer, some product.

So maybe the campaign budget is $45,000 for three months, I get a percentage of that to cover my costs. That’s how I operate. So I don’t need to make music anymore. Because the 21-year-old kid’s music is more relevant than my music from 20 years ago. I don’t need to compose songs. I don’t need to perform on stage. If I DJ, I do it in the sense of this new, 21st century term called curator. I’m familiar with what’s going on in Luanda. I’m familiar with what’s going on in Nairobi. I’m familiar with what’s going on in Accra. I see what matches and what pairs and everything. So I can compare your wine to food. I can curate it. But I still have the skills to manipulate turntables, CD players, iPods, whatever. Doesn’t matter.

Well, it’s just great to speak with you again. Good luck with all of it.