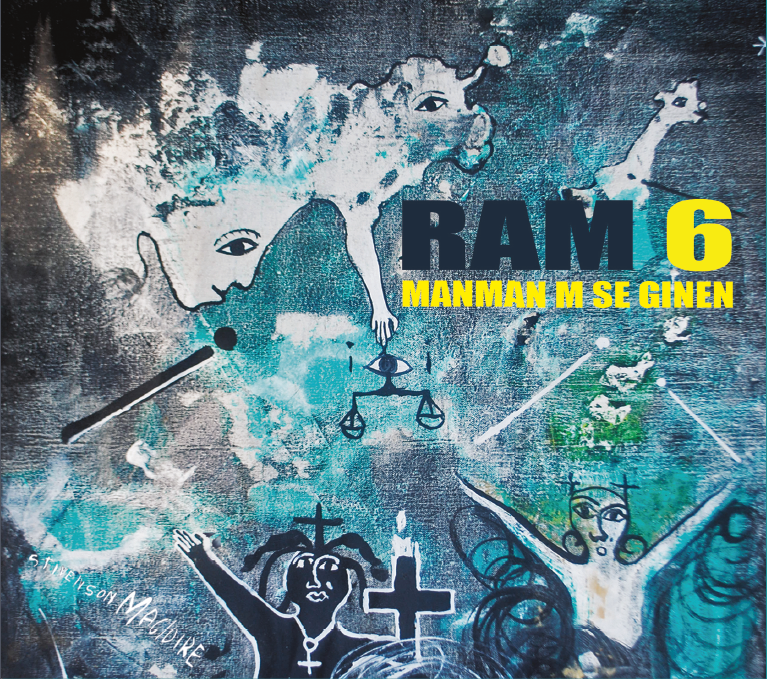

The new album from Haitian misik rasin group RAM is a lengthy jaunt that crosses and encompasses many moods and styles, but maintains a consistency rooted in vodou rhythms, memorable melodies, and tasteful instrumental accompaniment. The album starts with an aggressive rara track, “Papa Loko (Se Van)” which comes straight at you like an overnight express train driven by an outlaw: Rolling snares, haunting ostinatos of vaksin trumpets and a bevy of percussion announce the return of one of Haiti’s most locally and internationally acclaimed groups.

By the second song, the group relaxes into a comfortable konpa, “Jije'm Byen” led by the velvet voice of Lunise, backed by the characteristic chorus-drenched guitars and busy bass, pocket drums and percussion, with rara horns never far away.

The group, founded in 1990 in Port-au-Prince by Haitian-American musician Richard A. Morse and his wife Lunise, blends ceremonial vodou spiritual music with rock, a genre locally known as misik rasin (“roots music”). RAM caught their big international break in 1993, when “Ibo Lele (Dreams Come True)” was featured in the Hollywood movie Philadelphia, but they made a name for themselves in Haiti with a series of carnival hits and political songs criticizing Haitian dictator Raoul Cédras, and later Jean-Bertrand Aristide and his party Fanmil Lavalas. Ironically, Morse is a cousin of the ex-president of Haiti, Michel Martelly, whom he initially supported.

The music on RAM 6: Manman m se Ginen is as firmly rooted in Haitian vodou spiritual music as ever (Morse himself is a houngan, a vodou priest, as are other members of the group) and yet the new album also has influences from West and Central African popular music styles. There is a very literal connection between Haitian vodou music and West African traditional spiritual music, especially from the Benin/Togo/Ghana region, and yet RAM is doing a different sort of fusion: On the tracks “Ipokrit (Manje Bliye),” “Odan Bonswa” and “Koulou Koulou,” RAM blends Haitian konpa and rara rhythms with upbeat highlife and Congolese soukous, which blends seamlessly with konpa guitar and keyboard styles. Halfway through “Koulou Koulou,” the energy is lifted by an exciting call and response between rara horns and the male chorus vocals that harkens to a song or style that is so familiar, yet just beyond this reviewer’s conscious mind. At the end of “Ipokrit” a half-time keyboard breakdown leads right back into an uptempo dance party.

There’s also a softer side of this album, from “Tout Pitit,” a deliciously melancholic konpa, to the opening of “Ogou O,” a gorgeous ballad to the loa of iron and war, Ogou, which transforms into a feature of traditional songs, driving percussion with drum set accents. Similarly, the soft guitars of “Kolibri Ankò” leads intro the hard-driving “Kolibri Mèt Bwa,” a vodou rock romp with heavy percussion and guitars, with lyrics about the ‘hummingbird of the forest.’

With “Mon Konpè Gede,” RAM takes us to the cemetery, celebrating Gede, the top-hatted guardian spirit of death, with a relentless groove. But the penultimate track, “M'pral Dòmi Nan Simityè,” is by far the most exciting on the album: It opens with sounds of cheering crowds, and then a sudden assault of rara vaksins and punk-rock guitars and drums launch a raging rara rhythm with thumping bass drum, glittering metal bells, and hocketing horns.

RAM 6: Manman m se Ginen is a tour de force. Every track is a unique and tasteful mixture of sacred, secular, local, international and creative music. Bravo, RAM, and may the next 20 years be as fruitful as the last.

Also, be sure to check out Banning Eyre's review for NPR Music.