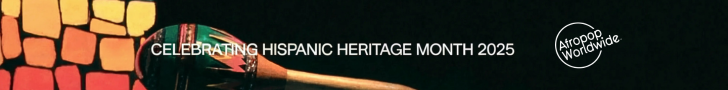

In the late '80s and early '90s, few groups in the British rave scene had the impact of Shut Up and Dance. Both a band and a label, Shut Up and Dance fused the strands of black Atlantic music, connecting hip-hop and dancehall to the emerging mainstream of acid house and hardcore. In doing so, they helped lay the blueprint for a generation of musical styles, including everything from jungle to grime and dubstep. Producer Sam Backer spoke to founders PJ and Smiley at their headquarters in Clapton.

Sam Backer: Can you start by introducing yourself?

PJ: We are Shut Up and Dance. We’re a group as well as a record label. Back in 1989—we, basically were rappers. We were British rappers trying to get a deal in the U.K. So we were British rappers, but our rap was different, our music was fast. We sped up a lot of beats because we were dancers as well. We were well into the hip-hop side of everything—break dancing, body popping. So when, we started to rap, our music was fast.

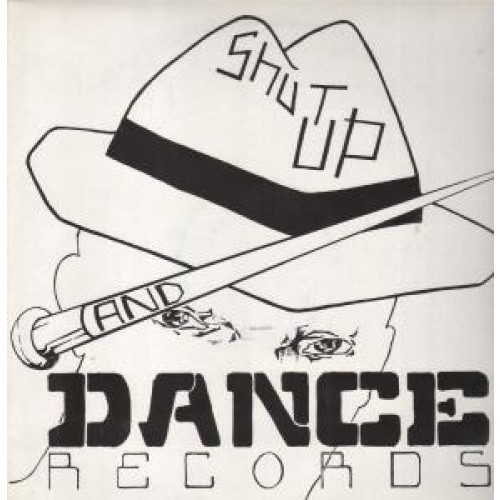

We were sending around this demo tape, trying to get signed as a U.K. rap band, and basically we weren’t getting anywhere. We were just being rejected left, right, and center. Looking back now it's because our music was totally different to what was happening. But we were young, and we said—“Look. Let’s just do it ourselves.” Back then that was unheard of. This was 1989, and no one did that themselves. They all signed to a big record company. But we decided we were going to do it, so we basically give ourselves a date and said we were to leave our jobs on that date, that we’d put our money together, and release a single. And that’s what we did! Our first single was “5,6,7,8” and as soon as that came out, everything just exploded. Back then we knew nothing about distribution, we knew nothing about what actually being a record company was. We were just determined to get our music out there. That was the one thing that was driving us.

So we had the single pressed up, we had it in the back of our car, driving around to record shops saying, “Do you want this tune? Do you want this tune?” Again—back then, that was unheard of. That first single, “5,6,7,8” was very successful, and then we went on to do other tracks—“£10 to Get In,” “£20 to Get In.” And everything we were putting out was getting bigger and bigger, and the label was getting more successful, and we got to the point where we had to sign other artists….but before I get there, I’m going to let Smiley interject, because he might have something to say [Laughs]

Smiley: I'm Smiley, the other half of Shut Up and Dance. The label was starting to blow up, so we decided that we had to sign other people to the label. It can't just be me and PJ putting out our own music. So anyway, we thought—“Right, we need to sign other artists.” Lots of our stuff, especially demos that hadn’t been out, had a reggae vibe to them, with a dancey, breakbeat-ey, weird beat that we’d come up with because we used to be dancers…. plus we were a hip-hop band. Or we thought we were! But it was always a dancey vibe, not this slow thing. We love that—don’t get me wrong—but we wanted to dance. And that’s why our music sounded like that.

Our music had lots of reggae b-lines [bass lines] in it, so we thought that for the act that we signed, we needed to get a reggae vibe in it, a reggae act basically, and put them on our beats. And we did it, and who signed was the Ragga Twins. They used to be on a sound system called Unity, and we sampled an intro from what they said at a sound clash. And I went to them personally, and said “I used this for a dance tune, for a sample tune, do you give me permission to do so?” and they were like, “Yeah yeah, cool cool.” And so we said, “We’re looking to do something with a ragga emceeing guy, would you like to come down, and hear what we got.” And so they came down with their entourage,

PJ: All 50 of them!

Really? 50?

Smiley: Yeah. Like literally 50… In my bedroom! [Laughs] The label was doing all right but, we were just in my bedroom. That was how the label was set up.

How did they have an entourage? Had they already been releasing records?

Smiley: No. They were just big in the sound system world. They were basically ghetto superstars. They didn’t really have any money, they weren’t drug dealers or anything like that, but they were big in the community.

They had a big sound system.

Smiley: They were like number one though, at the time. So we put them on our beats and everyone was like, “What?” When we signed them, I said, “Look. What we are doing with you is a total experiment. No one has ever done this before; this is something totally new that we want to try.” And that was how so-called jungle was born.

PJ: A lot of people now give us credit. Because back then, with all the elements that we did: getting break beats and double speeding them, pitching them, and then adding things like reggae elements, reggae bass lines, rap, and all of those things. Now everyone says that was basically the birth of drum and bass, jungle, whatever you want to call it.

Smiley: And then obviously from that, dubstep appeared. So we know that without us…I’m not saying that there would be no drum and bass, or there would be no dubstep, but it wouldn’t sound like that.

O.K. Let’s go back to the beginning for a minute. How did you first get into hip-hop?

PJ: Just in it.

Smiley: In it from day one.

PJ: Plus, back then, as a kid growing up, you just followed what America was doing.

Smiley: You eat, sleep, and breathe America. Plus, I was lucky because my mum… My mum left us as kids. She went to New York, so we had a little bit of contact. That’s how I got to go to America before anyone knew where the airport was, let alone going to America, do you get me? I was 11-12, when I was in New York, back and forth. So I got to see hip-hop, I got to see Run DMC when I was 16! I took three buses to go and find the concert, got lost, but I didn’t give a shit! I’m 16, I’m in New York, and Run DMC is playing! I begged my mom for the money and I found my ass there. I was only 16. So we was in hip-hop from the beginning.

And the dancing? Were you doing hip-hop dancing?

Smiley: Everything. Hip-hop, street. We thought we were in the film Breakdance! Or Beat Street. What the Americans were doing, we lived that.

PJ: Back in school days—we both went to the same secondary school—at lunch time, there would be body popping competitions. And we were there, giving it all…

Smiley: We just did what the Americans did. We emulated everything! Except for the violence… we didn’t get to that. Well obviously some people did but, we were too busy being in love with the music.

Were there other people trying to make hip-hop like you did?

Smiley: Oh God yes. There was a big movement in this country. This country was hip-hop fanatics! It wasn’t just us, seriously. You go to anyone from the ages of 35 to 55, and you go through their collection, and they’ll tell you everything you need to know. It was like the pop music of the day, for kids. It wouldn’t be on the TV, but every kid would know…

PJ: It was the youth culture. If you were young, that’s what you were into.

Smiley: No ifs or buts. You knew every lyric of every rapper, you knew everything.

So what year was this?

Smiley: This is throughout all of the '80s.

So did you play hip-hop out?

PJ: Back in the day, in addition to starting a label, running alongside that, we had our own sound system. Whilst all these other things were going on, the U.K. was going sound system crazy. So if you were anyone, or you thought you was, you had a sound system. So we had a sound system! Still have one to this day, a good sound system. Built by Smiley, and his brother, & Hype, because Smiley was into carpentry. His brother is a sparks, an electrician. So the sound system was myself, Smiley, his brother Earl [Daddy Earl] , and DJ Hype. And up to this day we still have a sound system.

Smiley: It’s the same sound system.

PJ: It still works, it’s still the same, and it’ll still blow away many a sound. Because now we’re all proper. I’m an MC, he's a DJ, so we’re proper now. Don’t mess with us! So every now and again, we dust off the sound, and play for like…a close friend’s wedding party or something. It’s very rare, but we do it for the hell of it. Just to get the sound out. And it’s great.

What's the name of your sound?

Smiley: Heat Wave. Go look it up online. You’ll find everything about all that. It’s legendary!

So when you were rapping, you already had the sound.

Smiley: When we were about 12 years old, we thought, “Yeah, we’re going to build a sound system.” We got together, and then we stole—beg, borrowed and stole—a sound system. Because we were just kids, with no money, no nothing. And we built a sound system. It’s true! When we was about 15 or 16 we played at our school, at our school prom, like a proper sound system. It wasn’t nothing, but we had a sound system.

So when we got up to about 18, we thought, Right, we gotta get the sound on the road. My brother was training to be an electrician, and I was trying to be a carpenter, making our speaker boxes better. And we started breaking into empty houses, and putting on blueses, dances. Putting out flyers, that we’re having a party at this place at this empty house. We’d check it every day to make sure that no one had moved in. We started small, like three rooms, and then you get bigger and bigger. And that's what we did from the age of about 16, we did it for about three years.

On the sound we were rappers, my twin brother Daddy Earl was the MC for DJ Hype—he was a reggae MC, and Hype was the DJ. So we had this unique sound system. Where most sound systems would play just reggae music, with reggae MCs chatting, or just soul music, we did everything, hip-hop, cutting up Peter Piper, cutting up reggae records, Super Cat, playing rare groove funky stuff, playing James Brown… And we were only 16 or 17, and no one was doing this, no one. Not in a hip-hop style.

That sounds awesome.

Smiley: Of course it was! It was f**king awesome, what are you talking about?

PJ: There was no one like us. No one like us.

Smiley: People used to come and fight around the decks, just to see what was going on. We had mic stands, we were all rapping. And this is on all night, All night. It would start about 11 or 12, and go until about 7 a.m.

That’s also probably why when you made music to rock the dance floor, it would rock the dance floor.

PJ: Yeah. Because we had that in us.

Smiley: Remember we had to entertain the kids of Hackney. Because only 17-year-olds were coming. Because we were kids. So only kids would come, and we would have a a big house—packed. Room to room packed, and this is what was going on.

I feel like that’s all the elements right there. You had dancehall, hip-hop, rare groove.

Smiley: Nobody was cutting up dancehall. Cutting it up on two decks. And this was in the '80s!

PJ: Live, while we were rapping on top. Cutting it up in front of your face…

You said that you just kind of started your own label…but why?

Smiley: We were forced into it. We didn’t want to.

So you were shopping the music around in the U.K.?

PJ: We were sending out a demo. We had a 10-track demo tape, which we were sending out to all of the big labels at the time that were signing U.K. hip-hop. Labels like G-Street, Music For Life, and a few others. They were the labels that you got signed to. But we weren’t getting any response, so…we just grew hungry and annoyed and we said—“You know what, we are going to have to do it ourselves.” So we did.

When rave happened here…Did you guys go to raves? Were you in that scene at all?

Smiley: That’s connected to what we were saying. When we were going around in PJ’s car, selling our first tunes, the people that were buying the tunes were rave DJs. But we thought it was a hip-hop tune! Still do to this day. My younger brother used to go to raves, but we didn’t really go to raves. And he was like, “Ahhhh, f**king hell, man. They’re playing your tune, they’re playing your tune! In the raves, in the rave I went to. You need to come!” And I was like what? In a rave? And so we went down there, and….boy, they played the tune! And it went off!

PJ: Because we were making the music that we thought was U.K. hip-hop. That was 100 percent what we was. At the time, we had no interest in going to any other type of events.

Smiley: We had nothing against house or rave. I knew what the music was, I got the odd house tune or rave tune back then. But we was nothing to do with that. It was like a jazz tune getting played in a drum and bass club.

PJ: What helped us out, and what actually cracked that first single, was the pirate radio scene. In the U.K., it was very, very strong at the time. Especially in London, there were literally like 30 stations. You could just spin through the dial, and hear our tune. It was like this whole scene welcomed us in, but we were like, What is this scene? We were making it for that lot. But when we went there, and we heard it for ourselves in a club, we were like, we’ve got something here.

Did the music that you were creating change because of that audience? Because some of the tracks you released definitely had more of those rave elements.

Smiley: Yeah. It did. What we did then, was that we kept on doing the rap that we’d been doing, but we’d also do a B side which would cater more to the rave thing. Because we could seem to do the both. But realistically, the rap stuff was just for us, because we thought we were a rap band. We liked doing the rave stuff as well, so we put it on the B side.

Besides the Ragga Twins, you had other artists, right?

Smiley: Loads of artists. We had 30 artists.

Wow. I didn’t know it was 30.

PJ: One our biggest ones were people like Nicolette, Peter Bouncer. Those are the ones who had the biggest successes. Those guys, and obviously the Ragga Twins, and ourselves.

How did you hook up with Peter Bouncer?

PJ: Peter Bouncer was a reggae vocalist. He was also on the sound systems, he was another ghetto superstar really known in the scene. We liked him a lot. A great singer. So when we were looking to expand on the Ragga Twins, we thought we needed a singer, so naturally we turned to him.

Was that move unusual at the time? Pulling top talent from the Jamaican sound system culture in London.

Smiley: They’re English people. They’re English born and bred but… I know what you mean. You’re exactly right. I just want to clarify that they did not come from there, they came from here. We all went to the same school.

PJ: We knew these guys were talented, and we wanted to try what we’re doing. It was just one big experiment, try new things, try new things. How different can we push it? So we brought them into this world, just like how we got brought into this world.

Smiley: Because when they came to our world, they were like, What the fuck is this? when they were listening to the demos. But then they were like, I’ll give it a try. And then we got them a booking to promote the track, and we were like, You need to go to this place. You’re going to do a gig, and they’re paying you £1,000 pounds. And they’re like, What? And I’m like, Yeah, £1,000. Don’t forget to collect the money. And he’s like, What? ” He didn’t believe us. And they get there, and there’s a dressing room. And they’d never seen a dressing room, with their names on it. And they got to the backstage, and they could see the audience, a big, big crowd, and they said, There are just all white people! They’d never entertained white people, because they’re from the sound system thing, you know, black culture. And they’re like, F**king hell man, are they gonna like us? And then they came out, and did the track, and it fucking killed it. They smashed it, And it changed their lives, from seeing the world that we brought them to. Which is a beautiful thing.

So it really was one of the first time those cultures connected like that. Maybe there’s stuff earlier--I don’t know if lovers rock got on the top charts, but…it’s an important cultural crossover moment.

Smiley: It’s one of the biggest. It’s the biggest, I think!

PJ: Because it changed the sound of U.K. dance music.

Smiley: Before U.K. rave came along, and Shut Up and Dance, music was a very one sided thing. You was either into reggae or pop shit or soul, maybe you were an underground soul boy. And that was it. There was no music scene where the nation moved as one, and thousands would go. There was nothing. It was very mundane--you’re into this thing, he or she is into this thing, and that’s it. There’s not a big thing going on. Never been in this country, after like the Beatles and all of them boys finished. Then it went psychedelic, and nothing big came. But what we brought, what we helped bring…it changed the world.

Was there a moment during that period, for you guys, when you said, “Oh my God. This is changing.”

PJ: It was kind of like that from the first single. When we put out “5,6,7,8” it just went crazy. And it didn’t stop. You couldn’t have asked for a better introduction to anything, a career, job, anything. You couldn’t do better then what we did. And it was totally unexpected.

Smiley: We couldn’t press enough records! What a problem! [Laughs] Shops and everything, distributors, everything. They said, We want your tune, we want your tune, everyone, We want your tune, the guy up the road, We want your tune, some DJ, We want your tune, and we were like, yeahh….

Were you writing the tracks for the other artists?

Smiley: Everything.

The Ragga Twins stuff too?

Smiley: Everything, for every artist. Maybe one or two but…

So you were sort of like a dance music Motown.

Smiley: Yeah! People said that. And we blew them all out of the water. Every single one. Even the majors! We were that big in the scene. Even the majors! Because we were a label, it wasn’t just one act.

PJ: There was always something new coming. If it wasn’t from us, it would be from one of our artists. There was always something happening.

Smiley: And it was usually the biggest dance track out there! It just was. That was how it went.

Was the success hard? I mean, not to complain about it, but how did you make that transition from your bedroom to being one of the biggest dance labels?

Smiley: You just get on with it, because it’s like a merry-go-round. You just get up in the morning, We’d do our training, and start the day maybe around 11 o’clock, And then you could go until maybe 1 in the morning, and that was every day. You understand me? It’s like you’re on this thing that’s just spinning you around, and you’re just on it…So you didn’t get a chance to analyze or think, or check it out or nothing. Because you’re on this ride. There was no lull—there just wasn’t!

PJ: And obviously when you have a successful act you need to have an album. You can’t keep dropping singles. You release two or three singles, and then you need an album. And then you need a video.

Smiley: And then the video, and then the tour, and then the this and the that, and what about his single and what about his album…and you have another singer, what about me, what’s going on…it just doesn’t stop. Because remember, it wasn’t like we were a record label and now we have this good thing going. We were just two kids that wanted a record deal. We knew nothing about the business. Nothing. There’s a good blessing that there were distribution companies, because otherwise we’d be ripped off! We did kind of—well, we didn’t get ripped off, but sad things did happen financially, where a company has gone bust owing us hundreds of thousands of pounds, distribution companies. But that does happen… it happened to us twice!

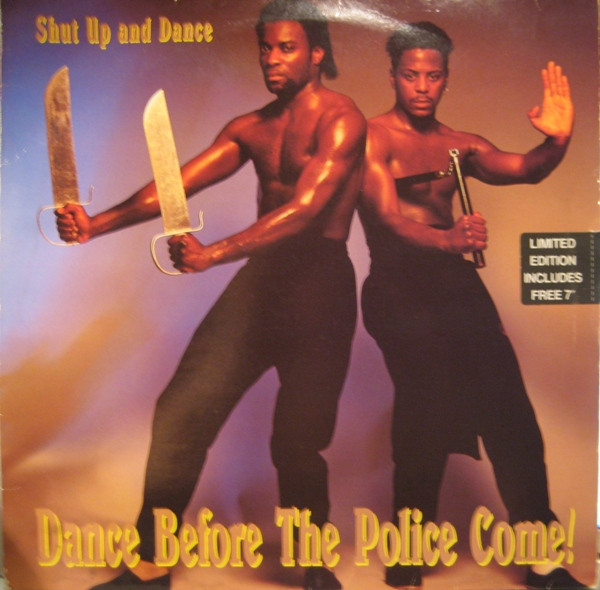

There was also a famous thing with a lawsuit with one of your tracks, right?

Smiley: That was “Raving I’m Raving” by Peter Bouncer. We put out the track and we tried to get permission from Warners, well, Mark Cohn’s people, but they said no. But we said, we’ve already pressed the track.

PJ: We didn’t put out the track. We’d put it on a promo.

Smiley: They were like, “No no no, we’re not giving you permission,” and we were like…come on, we’ve already got it out there! We’ll give you the royalties and the this and the that, but they were like no no no. And in the end, they said, All right. You can put out what you’ve already pressed up, but we need the rights and the tape and…that’s it. And that’s how it ended.

Did you run into trouble with your other tracks? Did the lawsuit change the kind of music you were making?

Smiley: It was just that one… and well, it was very timely in a way. In a weird way, because the whole rave scene had sort of ended when that happened. It sort of all went together.

What do you mean?

Smiley: Because the scene sort of finished when that all happened, do you know what I mean? It all ended with a damp squib sort of thing. The whole rave culture scene moved and changed, The music got harder and faster, the happiness thing went at the end of '92. In '93, there was no more raves in an illegal warehouse or a field because the police were on a hardcore lockdown, taking away people’s sound systems. And then this happened at the same time. It’s strange, isn’t it. The whole scene ended when that happened. It was just crazy.

I've heard from a bunch of people that '93, '94, everything splintered…

Smiley: That’s what I’m saying, the whole scene ended. It all splintered into a harder thing, and faster thing. The whole music went harder and faster…

But you guys kept on making music.

Smiley: Oh yeah. We never stopped.

So what kind of music have you been making lately?

PJ: It’s kind of hard to explain but we’ve always kind of just done our thing. But we make sure our thing fits in with what’s happening. It’s not like we’re lost in the woods, and everyone else is bopping away over there. Our sound is our sound, but we have to make it fit. And that’s how we’ve always done it.