Blog December 22, 2015

Remembering Bako Dagnon and Venâncio Mbande

As 2015 ends, we remember two giants of African traditional music who passed away earlier this year. Bako Dagnon was one of the most revered, deeply knowledgeable, and electrifying griot singers (jelimusow) of Mali; and Venâncio Mbande led perhaps the most powerful timbila orchestra in Mozambique. Both artists filled huge spaces in the traditional cultures of their countries. Fortunately, both have also left behind gifted musical families who will undoubtedly carry forth their ancient wisdom and personal brilliance.

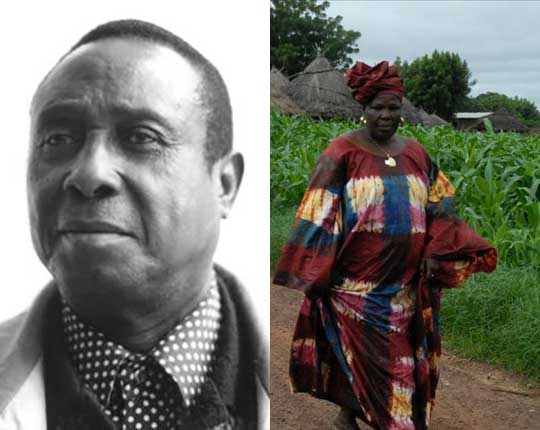

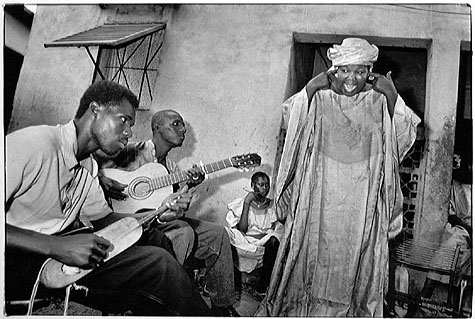

[caption id="attachment_26855" align="aligncenter" width="568"] Bako Dagnon[/caption]

Bako Dagnon (1953-2015)

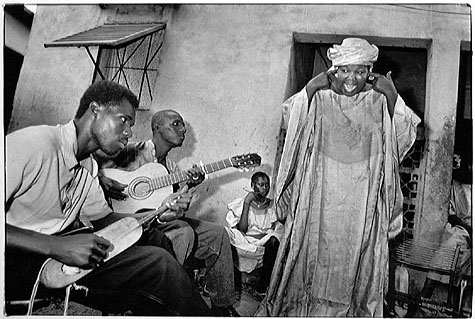

I first heard Bako Dagnon sing when I was living in Mali in 1996. She sang one song in a star-studded evening of music in a small stadium. My guitar mentor, Djelimady Tounkara, backed her up on a spectacular rendition of the Mande classic “Sunjata,” and it was the most powerful 10 minutes in a long night of great music. I later realized that both these artists hail from the area around Kita. It’s no accident that they tap into the deep musical roots of that fabled, culturally rich region of Mali.

Bako Dagnon was born in 1953 in Golobladji, a village near Kita. Lucy Durán wrote in her Songlines obituary that from a very early age, Bako, “learnt the craft of tariku (recitation of old historical songs) from the celebrated epic singers such as Kele Monson Diabaté. The song that launched her to fame, Tiga Monyonko (shelling groundnuts), is a tribute to a factory that opened in the 1960s in Kita; she used it to persuade farmers that the factory would help, not hinder them in their work. During the 1970s and early 80s she was lead vocalist with Mali’s state-subsidized Ensemble Instrumental National, with whom she traveled to China, where she sang Tiga Monyonko to Chairman Mao. She recorded two best-selling cassettes in the early 1990s, accompanied on kora by Ballake Sissoko, but they were bootlegged and she was discouraged from doing any further recordings until her two solo albums with the French label Syllart.

“Bako transcended politics and regional styles. Her exuberant and forceful personality, her sharp sense of humor, and her tendency to burst into song at any moment, made her a sheer delight to spend time with. She represented the last of the old school of griotism, only performing for the patrons with whom her family had long-established relationships. She was implacable in her criticisms of the young generation of griots, who she said were only interested in money--learning from cassettes, rather than from their elders. ‘If you want to hear the great singers, go to the cemetery,’ Bako would often say.”

Bako Dagnon[/caption]

Bako Dagnon (1953-2015)

I first heard Bako Dagnon sing when I was living in Mali in 1996. She sang one song in a star-studded evening of music in a small stadium. My guitar mentor, Djelimady Tounkara, backed her up on a spectacular rendition of the Mande classic “Sunjata,” and it was the most powerful 10 minutes in a long night of great music. I later realized that both these artists hail from the area around Kita. It’s no accident that they tap into the deep musical roots of that fabled, culturally rich region of Mali.

Bako Dagnon was born in 1953 in Golobladji, a village near Kita. Lucy Durán wrote in her Songlines obituary that from a very early age, Bako, “learnt the craft of tariku (recitation of old historical songs) from the celebrated epic singers such as Kele Monson Diabaté. The song that launched her to fame, Tiga Monyonko (shelling groundnuts), is a tribute to a factory that opened in the 1960s in Kita; she used it to persuade farmers that the factory would help, not hinder them in their work. During the 1970s and early 80s she was lead vocalist with Mali’s state-subsidized Ensemble Instrumental National, with whom she traveled to China, where she sang Tiga Monyonko to Chairman Mao. She recorded two best-selling cassettes in the early 1990s, accompanied on kora by Ballake Sissoko, but they were bootlegged and she was discouraged from doing any further recordings until her two solo albums with the French label Syllart.

“Bako transcended politics and regional styles. Her exuberant and forceful personality, her sharp sense of humor, and her tendency to burst into song at any moment, made her a sheer delight to spend time with. She represented the last of the old school of griotism, only performing for the patrons with whom her family had long-established relationships. She was implacable in her criticisms of the young generation of griots, who she said were only interested in money--learning from cassettes, rather than from their elders. ‘If you want to hear the great singers, go to the cemetery,’ Bako would often say.”

Only 63 when she died on July 7, 2015, this extraordinary artist clearly went to the cemetery herself far too early. But she leaves behind four children and many grandchildren, including at least one very talented young singer, Ami Diabaté. For an experience of Bako Dagnon, I highly recommend Lucy Durán’s wonderful film about her, “Voice of Tradition.” It is the third film down on this page of the Growing Into Music website.

[caption id="attachment_26851" align="aligncenter" width="596"]

Only 63 when she died on July 7, 2015, this extraordinary artist clearly went to the cemetery herself far too early. But she leaves behind four children and many grandchildren, including at least one very talented young singer, Ami Diabaté. For an experience of Bako Dagnon, I highly recommend Lucy Durán’s wonderful film about her, “Voice of Tradition.” It is the third film down on this page of the Growing Into Music website.

[caption id="attachment_26851" align="aligncenter" width="596"] Venancio Mbande (ILAM)[/caption]

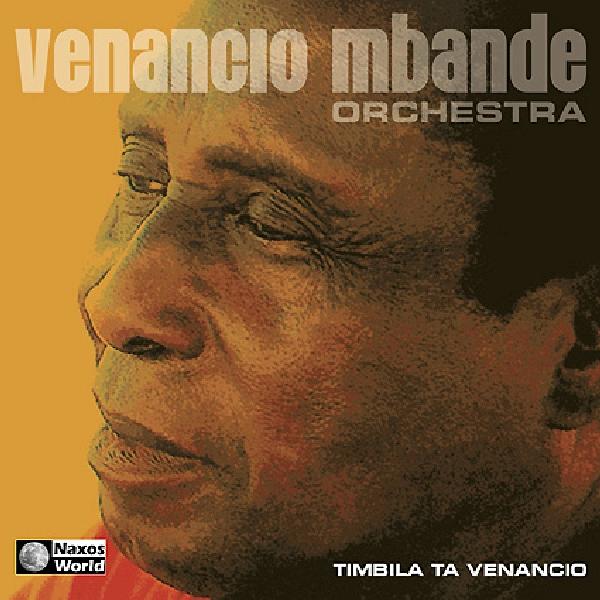

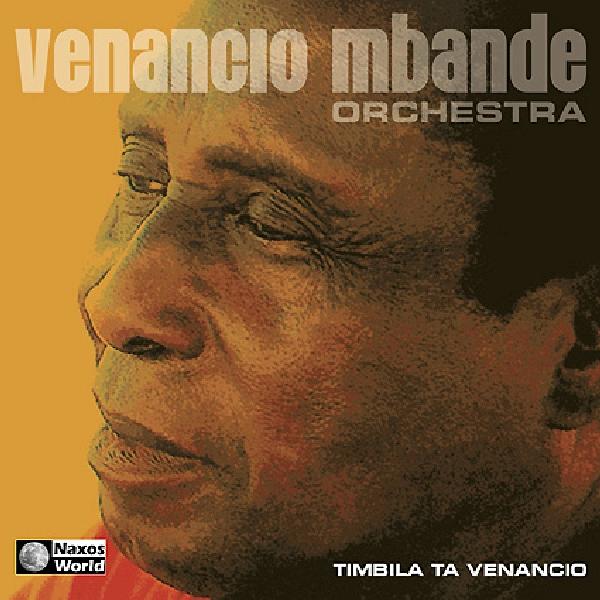

Venâncio Mbande (1933-2015)

Venâncio Mbande was one of the most important and under-recognized traditional ensemble leaders on the African continent. His instrument, timbila, is a xylophone unique to the Chopi people of Mozambique. Its sharp tones, complex polyrhythms, and buzzing timbre—produced by small calabashes with cow-stomach-lining membranes suspended below each slat—set timbila apart. The music is frenetic and joyous, utterly captivating once you adjust to its floating grooves and restless energy. Venâncio’s ensemble featured as many as 10 timbilas in different registers, creating a dense sonic web, filled out with percussion and vocals, all to animate a troupe of costumed dancers.

This ancient music endured a long brutal assault during Mozambique’s civil war (1977-92). Many timbila orchestras were destroyed or disbanded as villages were captured, overrun, and in some cases, wiped out entirely. The fact that Venâncio managed to keep his ensemble together through these deadly years is remarkable on its own. But after 1992, he and his musicians played a crucial role in a kind of timbila renaissance, culminating in an annual competitive festival staged by the Indian Ocean shore at Quissico’s Lagoon, near Zavala. The festival has become a regional favorite, and Venâncio’s ensemble performances there have been a mainstay.

[caption id="attachment_26848" align="aligncenter" width="602"]

Venancio Mbande (ILAM)[/caption]

Venâncio Mbande (1933-2015)

Venâncio Mbande was one of the most important and under-recognized traditional ensemble leaders on the African continent. His instrument, timbila, is a xylophone unique to the Chopi people of Mozambique. Its sharp tones, complex polyrhythms, and buzzing timbre—produced by small calabashes with cow-stomach-lining membranes suspended below each slat—set timbila apart. The music is frenetic and joyous, utterly captivating once you adjust to its floating grooves and restless energy. Venâncio’s ensemble featured as many as 10 timbilas in different registers, creating a dense sonic web, filled out with percussion and vocals, all to animate a troupe of costumed dancers.

This ancient music endured a long brutal assault during Mozambique’s civil war (1977-92). Many timbila orchestras were destroyed or disbanded as villages were captured, overrun, and in some cases, wiped out entirely. The fact that Venâncio managed to keep his ensemble together through these deadly years is remarkable on its own. But after 1992, he and his musicians played a crucial role in a kind of timbila renaissance, culminating in an annual competitive festival staged by the Indian Ocean shore at Quissico’s Lagoon, near Zavala. The festival has become a regional favorite, and Venâncio’s ensemble performances there have been a mainstay.

[caption id="attachment_26848" align="aligncenter" width="602"] Venancio and ensemble in Zavala (Eyre 1998)[/caption]

Venâncio made few commercial recordings. Timbila Ta Venâncio (Ekaya) is particularly recommended if you can find it. If not, search on that title on YouTube, and you’ll get a taste. Afropop once had the honor to interview and record Venâncio at his home compound in Zavala. We were directed there by one of his most devoted students, Nora Balaban, of the New York-based band Timbila. We arrived unannounced, to find that the group was away playing a ceremony in a remote village. We waited nearly 24 hours, and when they returned, exhausted and hungry, they gamely set up their instruments, donned their costumes, and performed once again before we shared a fine meal. It was a highlight amid 30 years of Afropop fieldwork.

Venâncio leaves behind a large musical family, including a number of precociously talented children and grandchildren. There is no doubt that they will carry forward his great legacy.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOWaJs8_Aac[/embed]

Venancio and ensemble in Zavala (Eyre 1998)[/caption]

Venâncio made few commercial recordings. Timbila Ta Venâncio (Ekaya) is particularly recommended if you can find it. If not, search on that title on YouTube, and you’ll get a taste. Afropop once had the honor to interview and record Venâncio at his home compound in Zavala. We were directed there by one of his most devoted students, Nora Balaban, of the New York-based band Timbila. We arrived unannounced, to find that the group was away playing a ceremony in a remote village. We waited nearly 24 hours, and when they returned, exhausted and hungry, they gamely set up their instruments, donned their costumes, and performed once again before we shared a fine meal. It was a highlight amid 30 years of Afropop fieldwork.

Venâncio leaves behind a large musical family, including a number of precociously talented children and grandchildren. There is no doubt that they will carry forward his great legacy.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOWaJs8_Aac[/embed]

Bako Dagnon[/caption]

Bako Dagnon (1953-2015)

I first heard Bako Dagnon sing when I was living in Mali in 1996. She sang one song in a star-studded evening of music in a small stadium. My guitar mentor, Djelimady Tounkara, backed her up on a spectacular rendition of the Mande classic “Sunjata,” and it was the most powerful 10 minutes in a long night of great music. I later realized that both these artists hail from the area around Kita. It’s no accident that they tap into the deep musical roots of that fabled, culturally rich region of Mali.

Bako Dagnon was born in 1953 in Golobladji, a village near Kita. Lucy Durán wrote in her Songlines obituary that from a very early age, Bako, “learnt the craft of tariku (recitation of old historical songs) from the celebrated epic singers such as Kele Monson Diabaté. The song that launched her to fame, Tiga Monyonko (shelling groundnuts), is a tribute to a factory that opened in the 1960s in Kita; she used it to persuade farmers that the factory would help, not hinder them in their work. During the 1970s and early 80s she was lead vocalist with Mali’s state-subsidized Ensemble Instrumental National, with whom she traveled to China, where she sang Tiga Monyonko to Chairman Mao. She recorded two best-selling cassettes in the early 1990s, accompanied on kora by Ballake Sissoko, but they were bootlegged and she was discouraged from doing any further recordings until her two solo albums with the French label Syllart.

“Bako transcended politics and regional styles. Her exuberant and forceful personality, her sharp sense of humor, and her tendency to burst into song at any moment, made her a sheer delight to spend time with. She represented the last of the old school of griotism, only performing for the patrons with whom her family had long-established relationships. She was implacable in her criticisms of the young generation of griots, who she said were only interested in money--learning from cassettes, rather than from their elders. ‘If you want to hear the great singers, go to the cemetery,’ Bako would often say.”

Bako Dagnon[/caption]

Bako Dagnon (1953-2015)

I first heard Bako Dagnon sing when I was living in Mali in 1996. She sang one song in a star-studded evening of music in a small stadium. My guitar mentor, Djelimady Tounkara, backed her up on a spectacular rendition of the Mande classic “Sunjata,” and it was the most powerful 10 minutes in a long night of great music. I later realized that both these artists hail from the area around Kita. It’s no accident that they tap into the deep musical roots of that fabled, culturally rich region of Mali.

Bako Dagnon was born in 1953 in Golobladji, a village near Kita. Lucy Durán wrote in her Songlines obituary that from a very early age, Bako, “learnt the craft of tariku (recitation of old historical songs) from the celebrated epic singers such as Kele Monson Diabaté. The song that launched her to fame, Tiga Monyonko (shelling groundnuts), is a tribute to a factory that opened in the 1960s in Kita; she used it to persuade farmers that the factory would help, not hinder them in their work. During the 1970s and early 80s she was lead vocalist with Mali’s state-subsidized Ensemble Instrumental National, with whom she traveled to China, where she sang Tiga Monyonko to Chairman Mao. She recorded two best-selling cassettes in the early 1990s, accompanied on kora by Ballake Sissoko, but they were bootlegged and she was discouraged from doing any further recordings until her two solo albums with the French label Syllart.

“Bako transcended politics and regional styles. Her exuberant and forceful personality, her sharp sense of humor, and her tendency to burst into song at any moment, made her a sheer delight to spend time with. She represented the last of the old school of griotism, only performing for the patrons with whom her family had long-established relationships. She was implacable in her criticisms of the young generation of griots, who she said were only interested in money--learning from cassettes, rather than from their elders. ‘If you want to hear the great singers, go to the cemetery,’ Bako would often say.”

Only 63 when she died on July 7, 2015, this extraordinary artist clearly went to the cemetery herself far too early. But she leaves behind four children and many grandchildren, including at least one very talented young singer, Ami Diabaté. For an experience of Bako Dagnon, I highly recommend Lucy Durán’s wonderful film about her, “Voice of Tradition.” It is the third film down on this page of the Growing Into Music website.

[caption id="attachment_26851" align="aligncenter" width="596"]

Only 63 when she died on July 7, 2015, this extraordinary artist clearly went to the cemetery herself far too early. But she leaves behind four children and many grandchildren, including at least one very talented young singer, Ami Diabaté. For an experience of Bako Dagnon, I highly recommend Lucy Durán’s wonderful film about her, “Voice of Tradition.” It is the third film down on this page of the Growing Into Music website.

[caption id="attachment_26851" align="aligncenter" width="596"] Venancio Mbande (ILAM)[/caption]

Venâncio Mbande (1933-2015)

Venâncio Mbande was one of the most important and under-recognized traditional ensemble leaders on the African continent. His instrument, timbila, is a xylophone unique to the Chopi people of Mozambique. Its sharp tones, complex polyrhythms, and buzzing timbre—produced by small calabashes with cow-stomach-lining membranes suspended below each slat—set timbila apart. The music is frenetic and joyous, utterly captivating once you adjust to its floating grooves and restless energy. Venâncio’s ensemble featured as many as 10 timbilas in different registers, creating a dense sonic web, filled out with percussion and vocals, all to animate a troupe of costumed dancers.

This ancient music endured a long brutal assault during Mozambique’s civil war (1977-92). Many timbila orchestras were destroyed or disbanded as villages were captured, overrun, and in some cases, wiped out entirely. The fact that Venâncio managed to keep his ensemble together through these deadly years is remarkable on its own. But after 1992, he and his musicians played a crucial role in a kind of timbila renaissance, culminating in an annual competitive festival staged by the Indian Ocean shore at Quissico’s Lagoon, near Zavala. The festival has become a regional favorite, and Venâncio’s ensemble performances there have been a mainstay.

[caption id="attachment_26848" align="aligncenter" width="602"]

Venancio Mbande (ILAM)[/caption]

Venâncio Mbande (1933-2015)

Venâncio Mbande was one of the most important and under-recognized traditional ensemble leaders on the African continent. His instrument, timbila, is a xylophone unique to the Chopi people of Mozambique. Its sharp tones, complex polyrhythms, and buzzing timbre—produced by small calabashes with cow-stomach-lining membranes suspended below each slat—set timbila apart. The music is frenetic and joyous, utterly captivating once you adjust to its floating grooves and restless energy. Venâncio’s ensemble featured as many as 10 timbilas in different registers, creating a dense sonic web, filled out with percussion and vocals, all to animate a troupe of costumed dancers.

This ancient music endured a long brutal assault during Mozambique’s civil war (1977-92). Many timbila orchestras were destroyed or disbanded as villages were captured, overrun, and in some cases, wiped out entirely. The fact that Venâncio managed to keep his ensemble together through these deadly years is remarkable on its own. But after 1992, he and his musicians played a crucial role in a kind of timbila renaissance, culminating in an annual competitive festival staged by the Indian Ocean shore at Quissico’s Lagoon, near Zavala. The festival has become a regional favorite, and Venâncio’s ensemble performances there have been a mainstay.

[caption id="attachment_26848" align="aligncenter" width="602"] Venancio and ensemble in Zavala (Eyre 1998)[/caption]

Venâncio made few commercial recordings. Timbila Ta Venâncio (Ekaya) is particularly recommended if you can find it. If not, search on that title on YouTube, and you’ll get a taste. Afropop once had the honor to interview and record Venâncio at his home compound in Zavala. We were directed there by one of his most devoted students, Nora Balaban, of the New York-based band Timbila. We arrived unannounced, to find that the group was away playing a ceremony in a remote village. We waited nearly 24 hours, and when they returned, exhausted and hungry, they gamely set up their instruments, donned their costumes, and performed once again before we shared a fine meal. It was a highlight amid 30 years of Afropop fieldwork.

Venâncio leaves behind a large musical family, including a number of precociously talented children and grandchildren. There is no doubt that they will carry forward his great legacy.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOWaJs8_Aac[/embed]

Venancio and ensemble in Zavala (Eyre 1998)[/caption]

Venâncio made few commercial recordings. Timbila Ta Venâncio (Ekaya) is particularly recommended if you can find it. If not, search on that title on YouTube, and you’ll get a taste. Afropop once had the honor to interview and record Venâncio at his home compound in Zavala. We were directed there by one of his most devoted students, Nora Balaban, of the New York-based band Timbila. We arrived unannounced, to find that the group was away playing a ceremony in a remote village. We waited nearly 24 hours, and when they returned, exhausted and hungry, they gamely set up their instruments, donned their costumes, and performed once again before we shared a fine meal. It was a highlight amid 30 years of Afropop fieldwork.

Venâncio leaves behind a large musical family, including a number of precociously talented children and grandchildren. There is no doubt that they will carry forward his great legacy.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oOWaJs8_Aac[/embed]