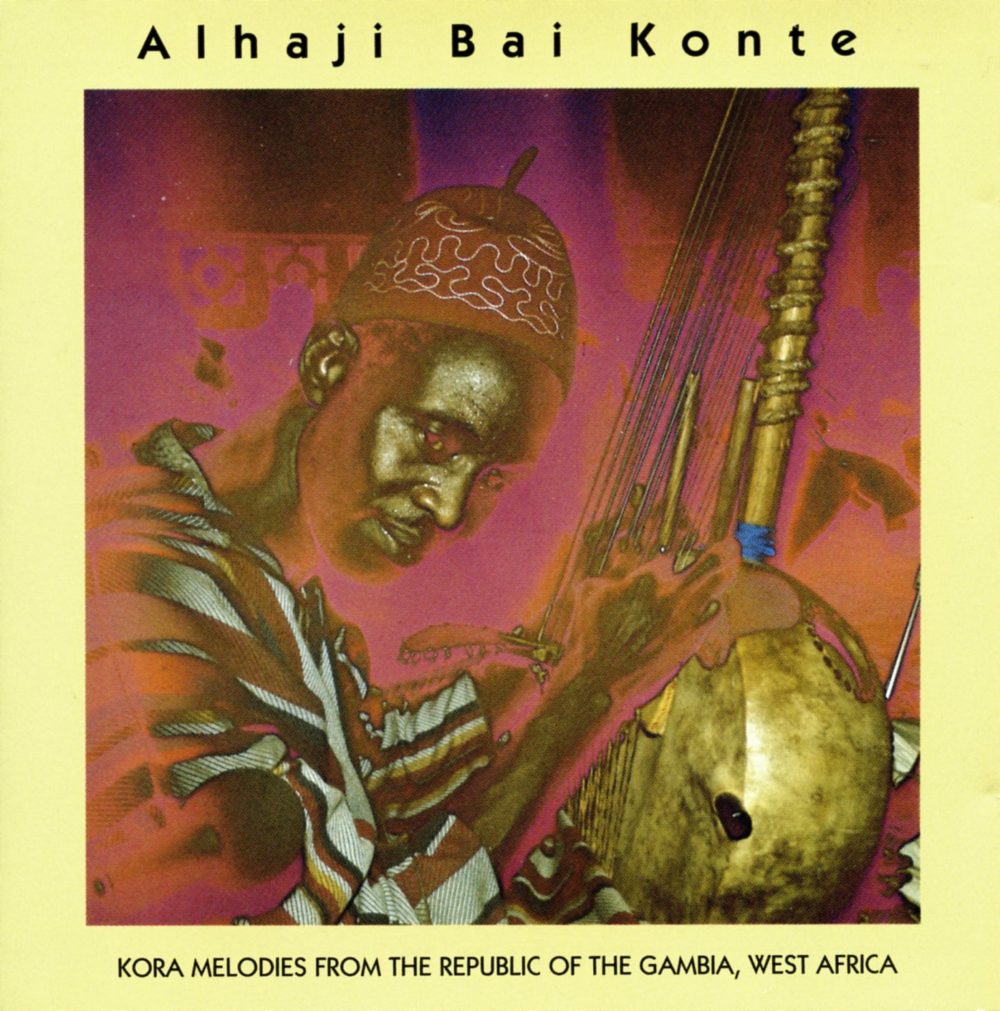

When fans of African music turn to the kora, the 21-string Mande harp, they tend to think of the great Malian players: the ubiquitous Toumani Diabate and his superstar son Sidiki, or Ballake Sissoko who has toured the world in a variety of ensembles, ranging from jazz and pop to semi-classical music. Historically kora did not originate in Mali, but further west in the Gambia, reportedly in a village called Brufut. In fact, it was Gambian players who introduced the instrument to the world, particularly the United States. In 1973, Rounder Records released Alhaji Bai Konte’s Kora Melodies From the Republic of the Gambia, West Africa. This album—mysterious, seductive, impossible to resist—was my introduction to kora and Mande music, and Sean Barlow’s as well; so in a real sense it is tied to the birth of Afropop Worldwide 35 years ago.

Bai Konte’s landmark album was recorded by American Marc Pevar. There’s quite a backstory there, but for another time. The remarkable update is that Pevar has remained connected to these revered Gambian griot families through all these years, and is now in the process of launching the Great Gambian Griots tour, featuring two exceptional purveyors of the Gambian tradition.

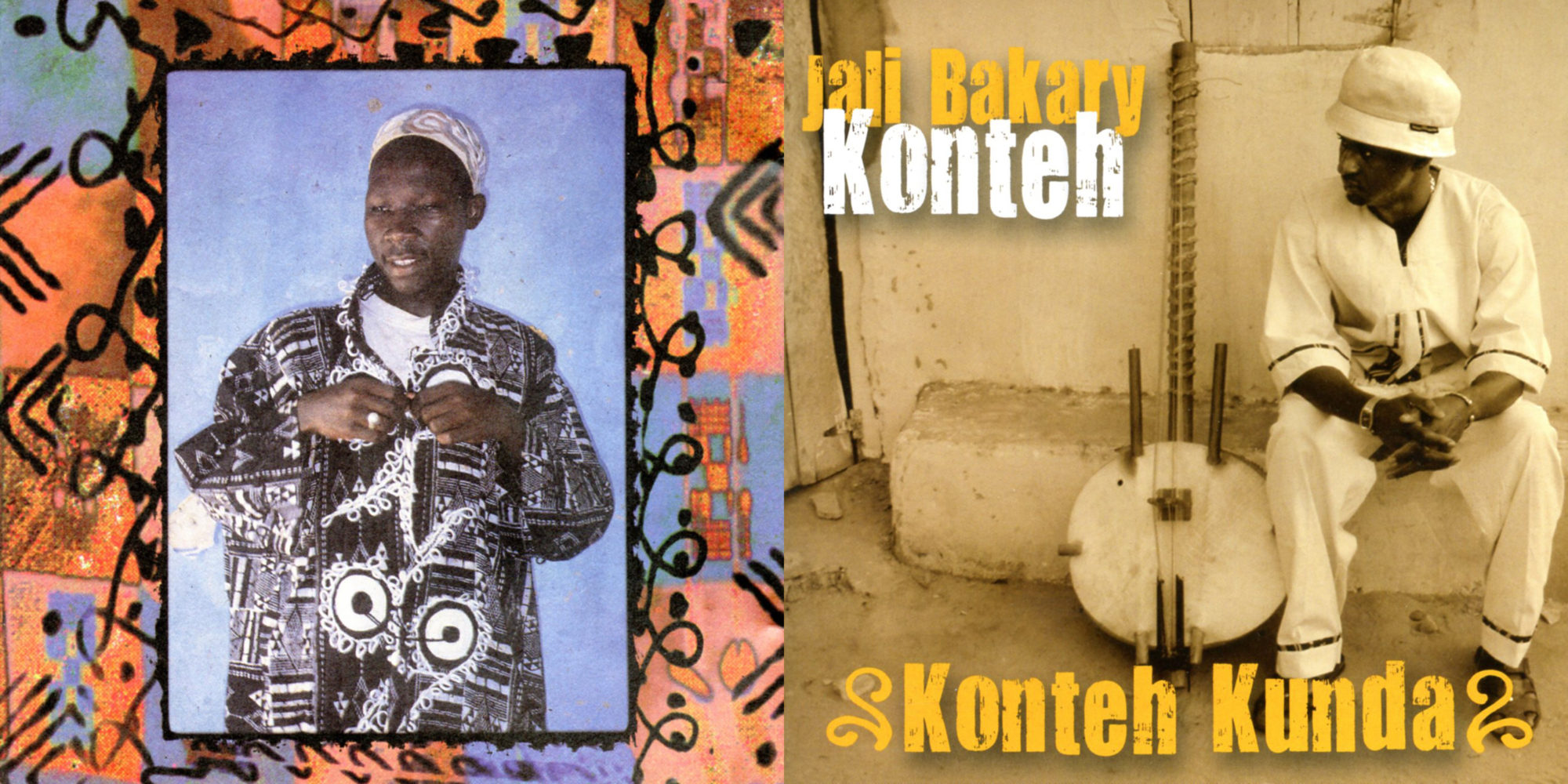

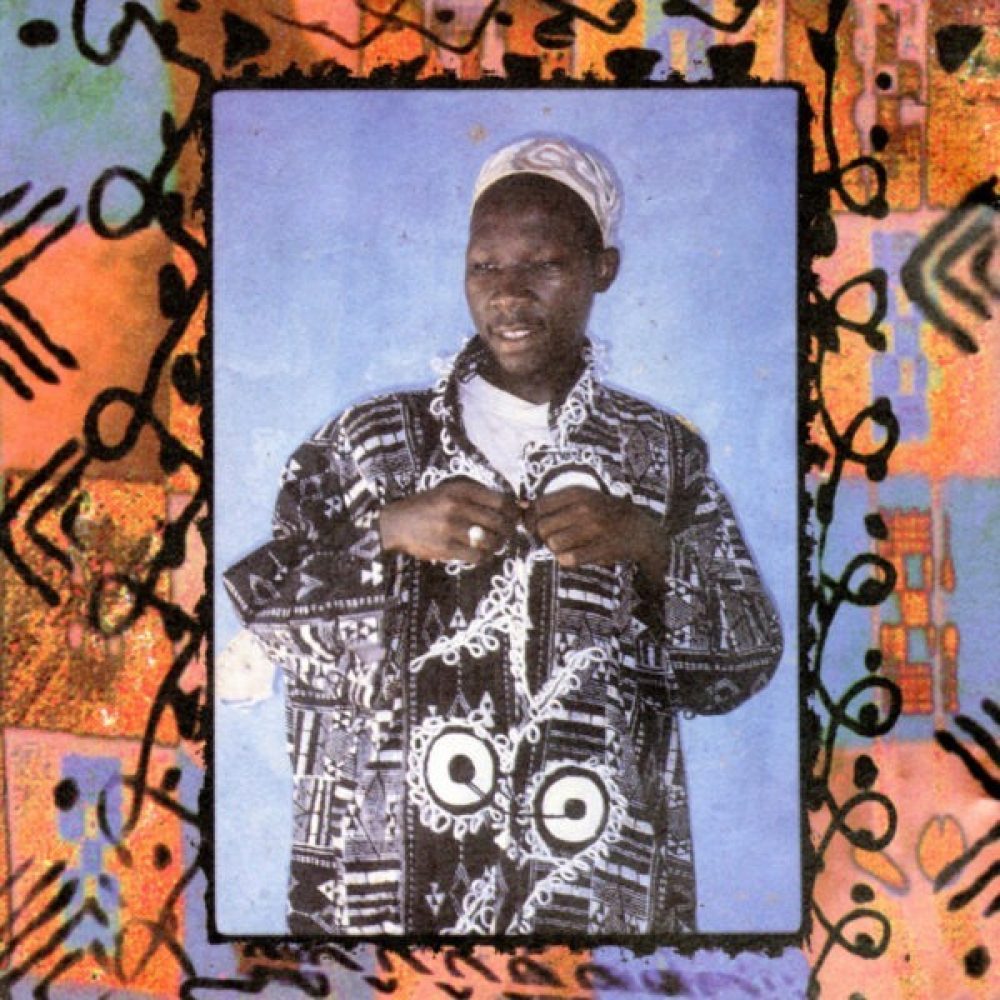

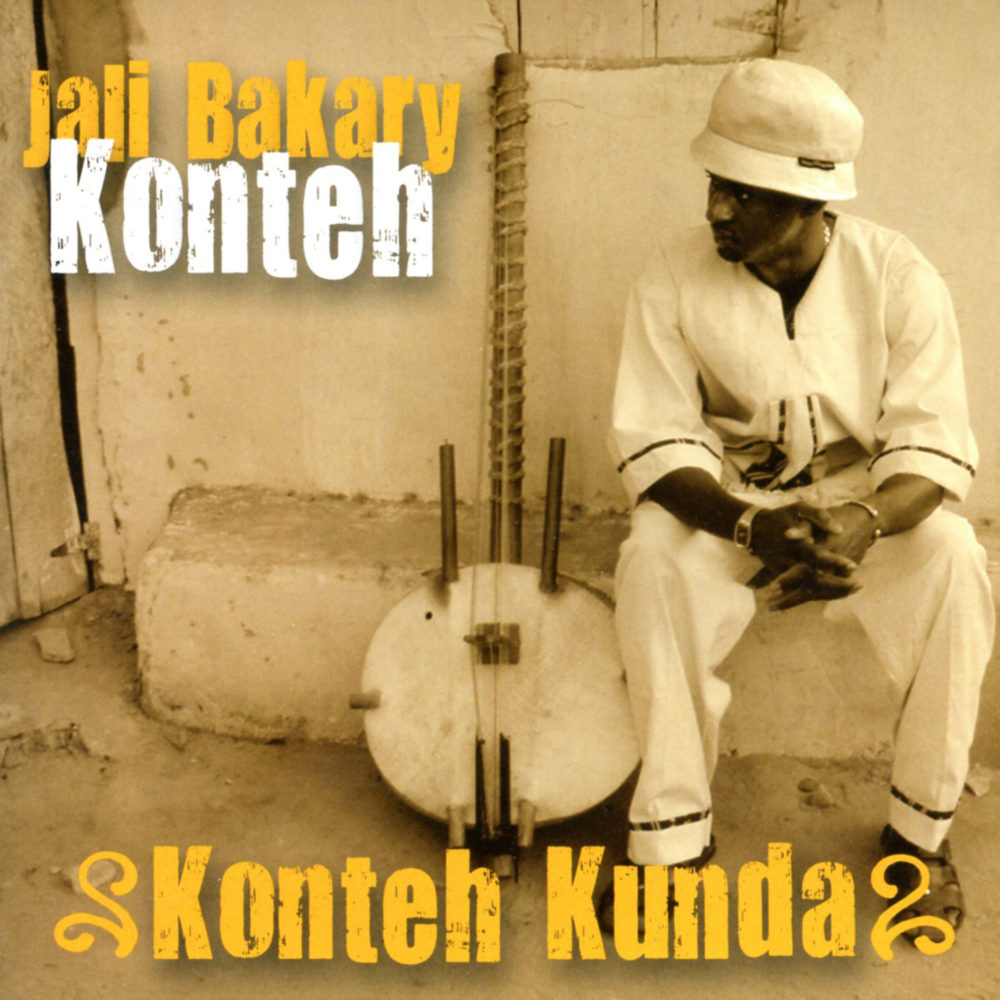

Jali Bakary Konteh is Bai Konte’s grandson, and Pa Bobo Jobarteh is Malamini Jobarteh's son, and a grandson to Keluntang Jobarteh: All three were great kora legendaries. Keluntang Jobarteh is a cousin to Bai Konteh, Pabobo Jobarteh and Jali Bakary Konteh's grandfathers respectively. Malamini lost his father and mother at an early age and was raised/adopted by Bai Konteh and his wife Aja Naffie Kuyateh who also happened to have shared the same mother and father with Bintou Kuyateh, Malamini's mother. The family tree gets a bit byzantine, but suffice it to say that this is a royal family of Mande music. The two grandsons’ fathers—Dembo Konte and Malamini Jobarteh respectively—also had distinguished turns on the world stage. But now that they are gone, the moment for Pa Bobo and Jali Bakary has arrived.

Back in 1973, Alhaji Bai Konte’s appearance on the American folk scene shook it to its core. Artists from Pete Seeger, Taj Mahal, Paul Winter, David Amram and Elizabeth Cotton, to Judy Collins and Bernice Regan (Sweet Honey In the Rock) got the message immediately. In one interview, Seeger said, “When the history of the world’s musics will be written, I guess we’ll find out how one continent has affected the culture of another continent and not given any credit for many years.” And that is literally true. Among the African nations that contributed to the formation of American folk music, Gambia was absolutely in the mix. Africans brought to Louisiana by the French crown during the late 1700s and early 1800s mostly came from the Senegambia region, including current-day Gambia.

Here in the present, it’s no surprise that the coronavirus pandemic has put a crimp in the planning for Marc Pevar’s Great Gambian Griots tour, but only temporarily. Both Gambian artists are getting set up to stream performances over the internet, and venues including the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, which was going to present the act this year, remain ready to do so when the time is right. In the meantime, the artists will soon reissue two of their own recordings, long since out of print, in both physical and digital formats. Pa Bobo Jobarteh’s Kaira Naata, and Jali Bakary Konteh’s Konteh Kunda showcase the state of the art of the Gambian kora tradition in the hands of young masters, and the music certainly whets one’s appetite for live performances, whenever they become possible.

It is difficult to overstate the regal, nearly divine, stature of the Konte and Jobarteh families in the echelons of African music. Aside from their late, iconic fathers and grandfathers, they each have siblings, cousins, uncles and so on who contribute to this vital living tradition. Griot families are more like root systems than linear progressions. So the fact that Pa Bobo and Jali Bakary have risen to the top is testimony to their excellence. Another thing that unites them is their desire to share the tradition, including their personal innovations, with the larger world, just as their fathers and grandfathers did.

Both artists have established touring careers—although mostly in West Africa and the U.K. Jali Bakary got his international due in 2016 when he won a national world music competition in the U.K. and was awarded a chance to perform at the WOMAD BBC-Introducing stage. Pa Bobo was recognized early on as Malamini’s child prodigy. He first performed at the WOMAD festival in the U.K. when he was just 11 years old.

Pa Bobo has since revived a neglected aspect of griot tradition—the responsibility to point out official wrongdoing, rather than simply praising. Merging griot oratory and rap, Pa Bobo’s songs of social activism--like “Peace, Love and Unity,” “New Gambia” and “World in Peace”—got him in so much trouble with the then authorities in Gambia that he had to escape to Senegal for a time.

But coming back to the music, consider this a pre-release preview of the two albums soon to hit the market. In 1997, following Pa Bobo’s return to the WOMAD festival, a team from Peter Gabriel’s WOMAD Select label traveled to Gambia to record Pa Bobo on his home turf, and that’s what we get on Kaira Naata. The album mostly features the Kaira Trio, a subset of Pa Bobo’s long-standing Kaira Band. With Haruna Jassy on balafon and Dawda Jobarteh on percussion, the trio reshapes traditional pieces into highly original compositions. The opener, “Mam Dou Sayang,” sets a tranquil mood, with kora and balafon intertwining lyrical lines that feel closer to the Malian style. But don’t be fooled. Even when he plays solo as on “Kora: Lonely Feeling,” or “Sara Bamba,” a praise song to warriors, Pa Bobo juxtaposes serenity with the lightning-fast riffing that has always been a mark of the Gambian style.

The album’s title track showcases tumbling percussion, sharp balafon and Pa Bobo’s keening vocal. Near the end, kora and balafon exchange racing, staccato solos—quite exhilarating. “Pa Bobo Naata,” another trio piece, unfolds at a canter, but when Pa Bobo cuts loose on kora, his style is positively ripping, even aggressive. The notes don’t so much cascade as Toumani Diabate’s might, but spit forth with the sonic force of a machine gun—even more exhilarating!

There are calmer pieces as well. “The Late Alafie Koko,” opens with the sound of waves on the beach where the track was recorded. The song honors a childhood friend who died on that beach. Balafon, kora and male and female solo voices conjure gentle, reflective sadness, but in the end, Pa Bobo reaffirms life with darting kora melodies even as his vocal nears a sob. The solo instrumental that concludes the album is a virtuoso tour de force. But the wildcard in the mix is “Saliya,” a live recording of the full Kaira Band—including guitar, trumpet, bass and drums—performing live in Brikama. The amplification gear is sub-optimal, but the energy of the performance comes through. This song, about the advice of a good brother, bristles with rock ‘n' roll exuberance. As great as it is to savor an authentic West Africa live scene, one thrills to imagine what this lineup could do in a recording studio.

Jali Bakary Konteh’s Konteh Kunda is a more produced recording, while still retaining a warm, acoustic quality. The title refers to the Konteh family compound in Brikima, Gambia, where the basic tracks were recorded, with solar power yet. Additional elements were added in the U.S. under the direction of multi-instrumentalist Steve Pile. Konteh’s strength lies in his big, rich kora sound. He can certainly riff in the classic Gambian manner, but he is less apt to turn on the fire the way Pa Bobo does. He demonstrates an impressive command of ways to turn kora-driven Mande music into full ensemble sound with engaging arrangements, inviting grooves and just the right addition of non-traditional elements. The textures and flows are original, never rote, and the whole album has a clean, well-rounded sound.

The band delivers a robust, one-drop reggae take on “Jaraby,” the romantic Mande classic, beloved for its message that one should be with the one they love—a clever ambush on the practice of arranged marriages. Aramatou Jobarteh sings the female lead here, and Pile takes a bluesy guitar solo while Konteh mostly lays back, surrounding the mix in lush kora tonality.

“Combination” unfolds in a rolling semi-clave feel in the drumming, while the bass holds the downbeat. The whole arrangement revolves around a catchy kora riff. The arrangement recalls the groundbreaking late '80s sound of Salif Keita. After an elegant kora break, the band pounces back with fluttering flute and then dives into a rich baritone sax solo. Konteh revisits classic Gambian kora songs, including “Allah L'a Ke,” which gets a solo treatment. His vocal is subdued, but his kora playing is brisk and sprightly, with the playful darting quality that distinguishes the Gambian style. Similarly, on “Jato,” "The Lion," a Konteh family favorite, Jali Bakary’s kora lopes and tumbles, his voice blending into the kora than riding over it. In the last section, he reveals his true prowess with urgent cascades and tremolos—just wonderful. Like Pa Bobo’s album, the set ends with a kora solo, “Nyang Tareya,” once again animated, precise and beautiful.

One can’t listen to these fine recordings and not wonder what it would be like to see these two world-class artists on stage together, carrying one of the most profound musical legacies of West Africa proudly into the 21st century. We wait hopefully to see if and when Marc Pevar’s dream will be fulfilled. As they say in West Africa, “In sh’Allah”—if God wills it.