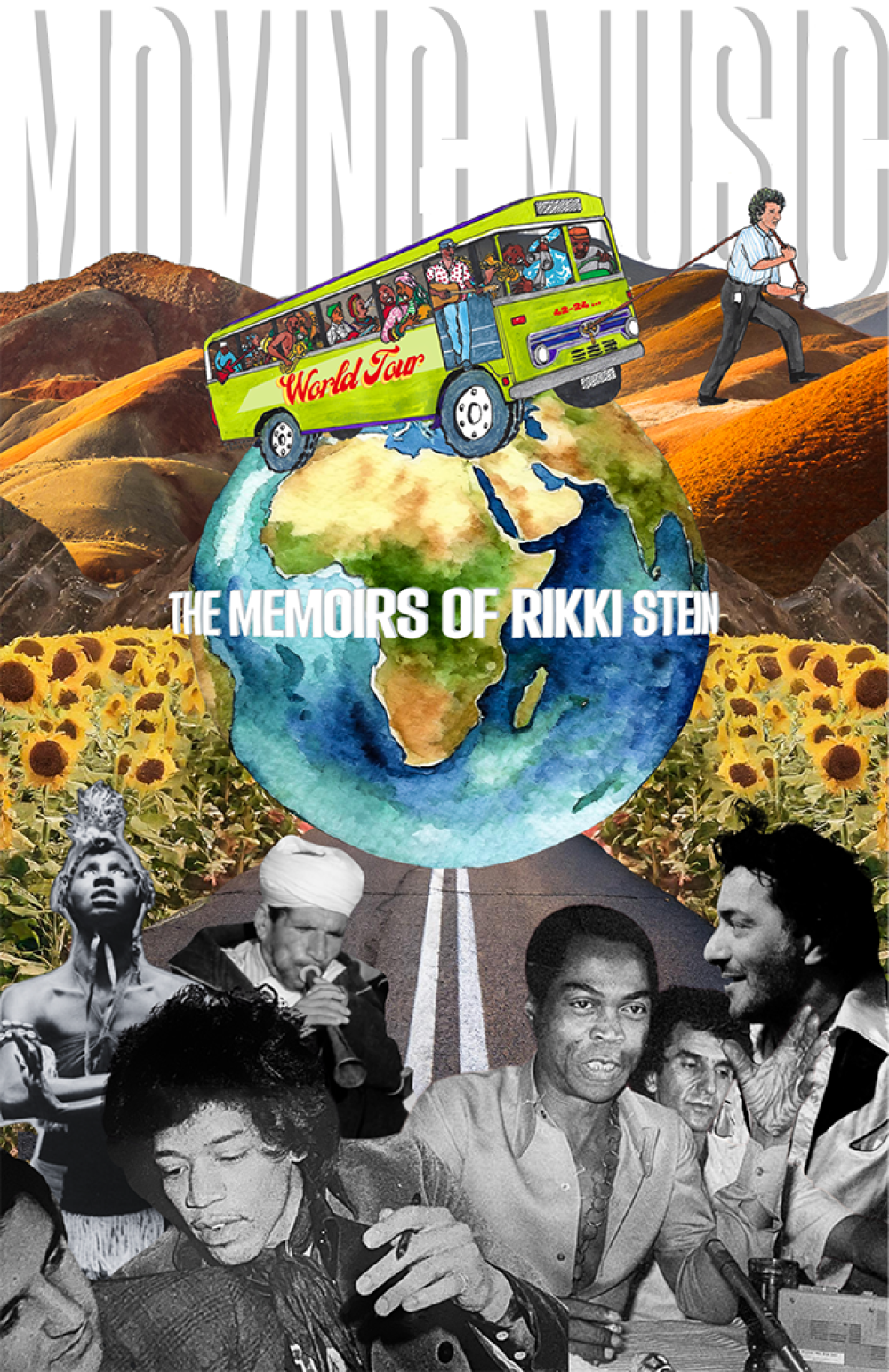

Even if you are a longtime fan of African music, you may not know the name Rikki Stein. But Rikki is one of those people behind the scenes that makes things work, and the world go around. Over the years he has managed the Master Musicians of Joujouka, Les Ballets Africains de Guinea, Keziah Jones, The Pan-African Orchestra and, most famously, Fela Anikulapo Kuti. It’s probably fair to say that no non-Nigerian was more of an inside player in Fela’s career than Rikki. Even if you know all these things, there are more surprises for you in his new memoir, Moving Music, The Memoirs of Rikki Stein (Wordville). After reading the book, Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Rikki in a video call from London to talk about it. Here’s their conversation.

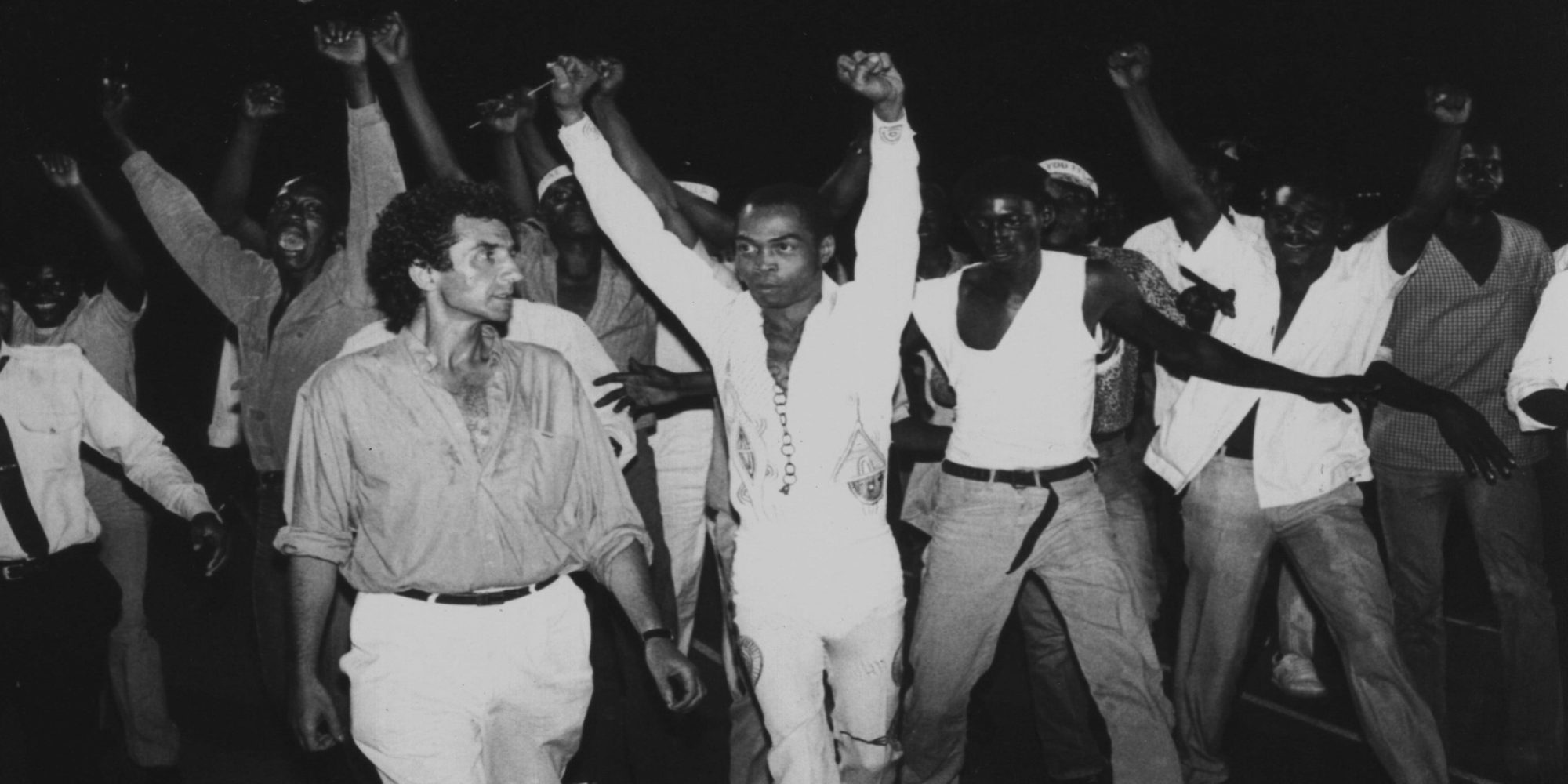

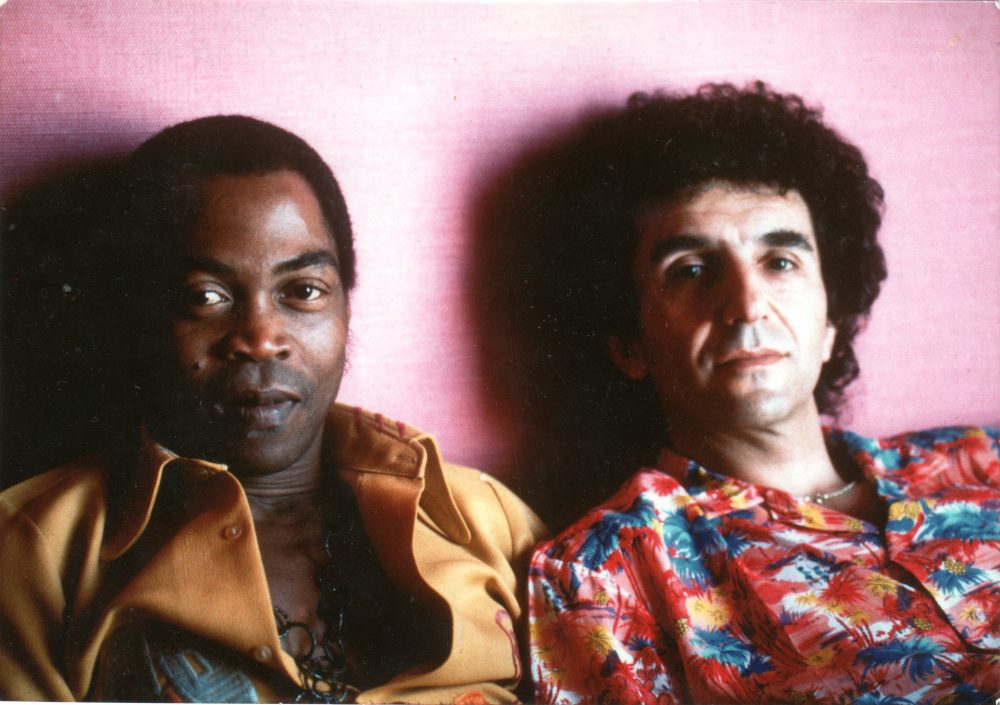

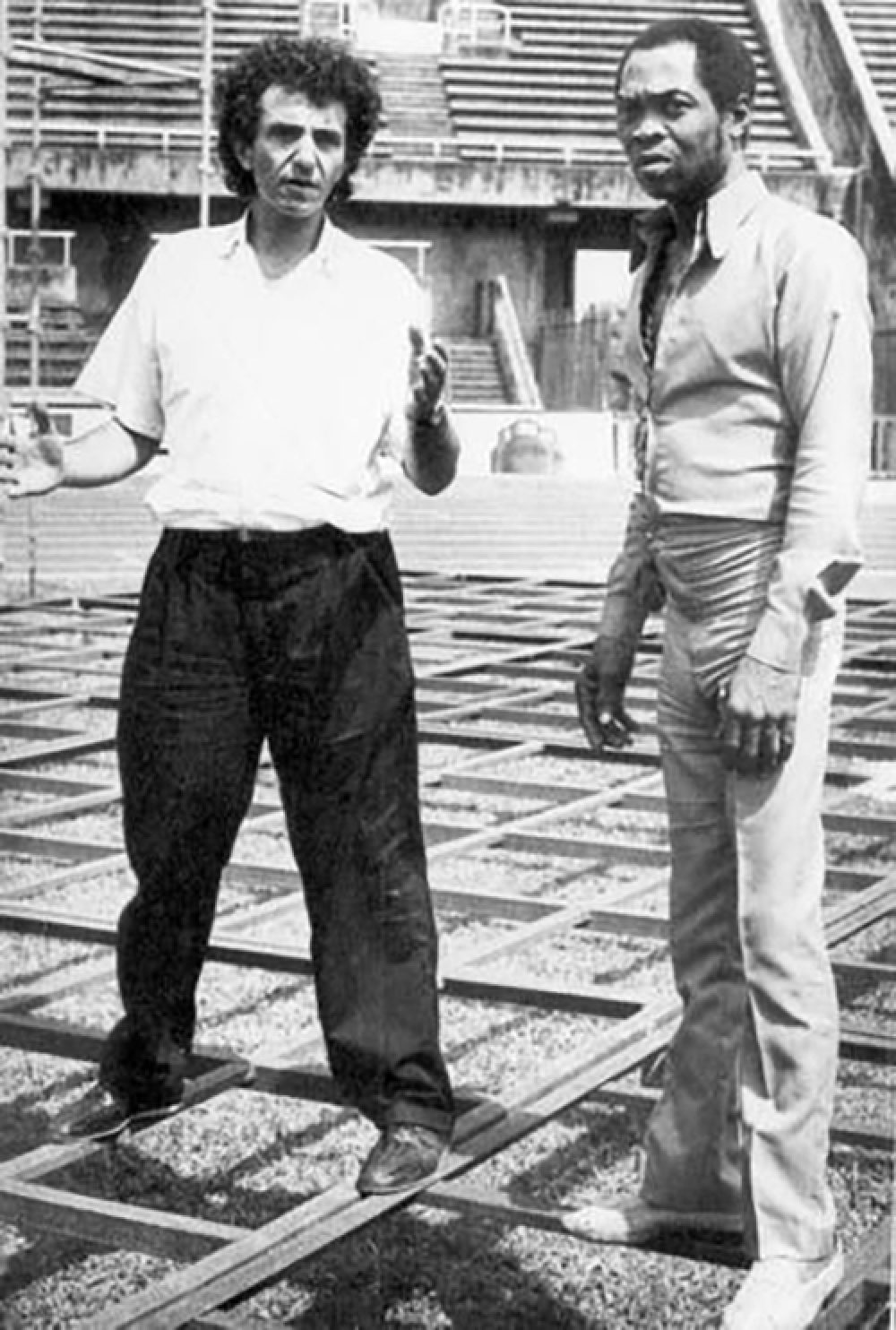

Banner image shows Rikki and Fela upon Fela's release from prison in 1986.

Banning Eyre: Rikki, How are you today?

Rikki Stein: I'm good, thank you. All is well. You're looking good too.

Thank you. Well, it seems like a lot of people of our generation are writing books now. I don't think I'm quite ready to do that yet, but I'm thinking about it. You took the opportunity of the pandemic to get around to writing. Do you think this would have happened without Covid?

I doubt it. Honestly, I doubt it, because I'd made stabs at it earlier. I'd written a couple of chapters, you know, but I'm busy, man. You know, you need to be able to devote yourself. I couldn't have just dashed off a couple of chapters in between meetings. And then Covid came along and it was a wonderful opportunity that I grabbed with both hands.

You say right up front that you are a compulsive manager, and you prove that in the pages that follow. Where do you think that comes from, this desire to be the one who's outside shaping these events and these people's lives and careers?

I really don't know. I can't help it, man. If I go to a show, I'm sitting in the audience looking at the stage and I find myself saying, that hi-hat looks like it's going to fall off the stand. I just want everything to go right, I suppose. And I found music to be just as good a field of endeavor as any other that I might have selected. When you finally pull it all together and everybody's loving it, you just feel, “Hmm, I did something right here.” It's like some kind of benediction. It's that spiritual moment when you're there and the music's happening and the people are responding and all the bullshit you've gone through suddenly seems worth it.

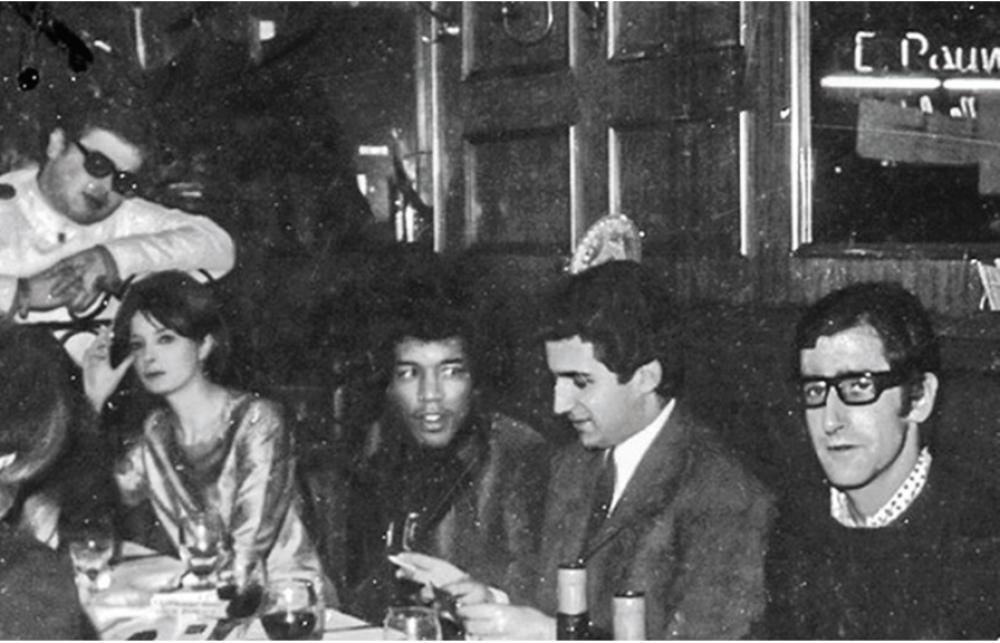

You have that experience over and over again in these pages. I knew of you first through Fela and then the Ballets Africains, but I really didn't know all your earlier adventures in the European rock scene, The Kinks, Hendrix, the Grateful Dead… Lots of adventures. And then your years in Morocco with the Joujouka musicians. All that before we get to Fela. As I read, I did feel that yours is a life worth documenting.

Thanks. It felt that way to me. Look, I've had a great time. Let me write it all down and maybe other people might get something out of it.

You seem to have a unique ability to earn people's trust and confidence quite quickly. Over and over again in these pages, you find yourself on the inside track with all sorts of characters making big things happen. It’s not always easy to do that, but you clearly have a knack.

It's a two-way street though, isn't it? You meet somebody, you like them, and happily they seem to like you too. So on that basis, it's a foundation on which one can move forward. Yeah, suppose I've been lucky in that regard. I do make friends quickly; it's true.

There's skill in it, of course. It's not all luck.

I don't know that I'm necessarily applying any particular skill other than just being who I am, and a take-it-or-leave-it kind of thing. Fortunately, some rather gifted people have chosen to take it, on which basis I've moved ahead. I've always found that people say you shouldn't work with friends. I only want to work with friends, you know? You can say more or less anything to your good friend, right? More or less. When it’s just pragmatic, people say, “Rikki, you're good at what you do. You should be managing the Spice Girls.” And I say, “If you want to do that, go do it, man. But it's not for me. I need to be able to stand at the side of the stage or wherever I am and feel proud of what I've presented.”

There have been occasions on which I've veered from that and said, “Okay, let me try and make some money with this.” But I've never been happy, you know? It's never been fulfilling in the way that working with Fela or the Ballets Africains or Joujouka or any of those other artists that I've had the privilege of representing.

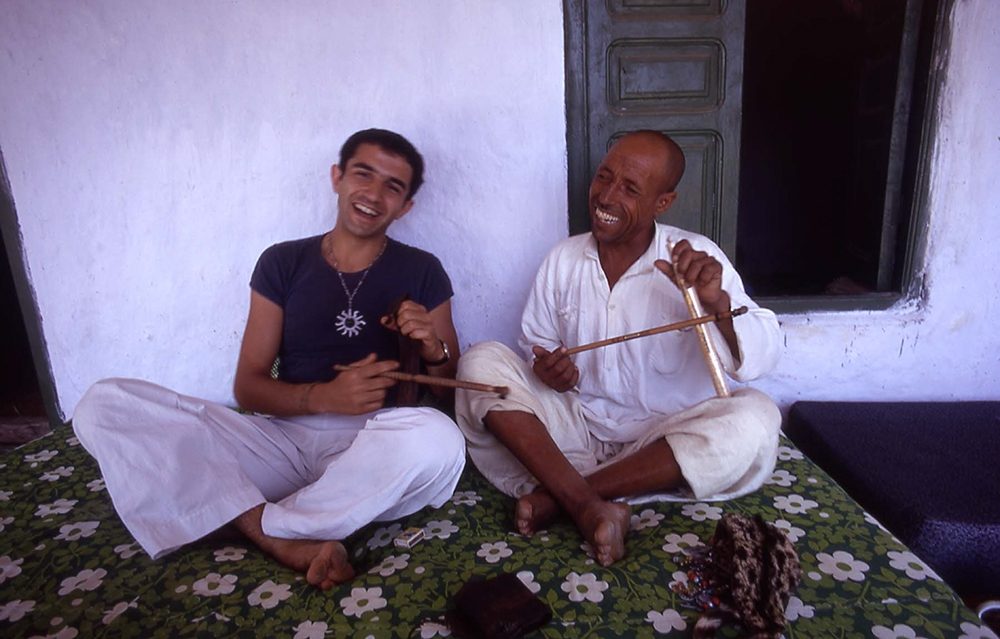

I particularly enjoyed the chapters about Joujouka. I haven't actually had the experience of visiting them in Morocco, but I've been close to it through my work. I loved Augusta Palmer’s film about her father’s (Bob Palmer’s) time there, The Hand of Fatima. And I interviewed the Joujoukans lead by Bashir Attar. But you really joined the community for a while. It's so interesting to me that you, as a secular Jew, go into this situation in a country where Jews have had a tough history, but you manage to pass as a local. Your appearance is almost a sort of camouflage.

Well, first of all, it wasn't a disguise. I had long hair when I first went to Morocco. I immediately cut it off, not to disguise myself, but just to assimilate myself. You know, it was more comfortable for me to walk around. And I've got semitic features, so it was easy. People thought I was Moroccan, but I wasn't pretending to be Moroccan. It wasn't anything deliberate on my part. It was just fortunate, you know.

Sure. It opened doors. And then ultimately, being Jewish became a problem when you were selling things to tourists out of a shop in Fez. You had to leave.

Yeah, I don't know what they thought I was, but whatever it was, they were uncomfortable. That was when I was working in the Fez medina. I think I was just quite good at my job, sitting on a stool outside the shop, wearing a jalaba and a caftan. Tourists would be coming down the hill and I’d say, “Hello mate, how's it going?” And they go, “Where are you from?” I’d say, “Walthamstow, East London. You wanna come in?” And of course they would come in and I'd give them mint tea and a kif pipe to smoke. It was easy for me, so maybe there was jealousy from some of my competitors in the bazaar who said, “We've got to lose him.” But you know, I rode out a year or so there, and it was good.

I've been to Morocco. Tangier, Fez, Rabat. But not enough. Morocco is a place I want to go back to.

Wonderful country.

The way you operate is impressive. You always seem to have your own program. You're making all the decisions and sometimes rubbing other people in the world music world the wrong way. Did you ever feel like an outsider in that world? I’m thinking particularly of the ups and downs of your years involved with the Glastonbury Festival.

Well, it was never really challenging. I've always taken, as you said, my own path, and at points where it's intersected with others, I've done my best. I was part of the Glastonbury crew right through the ‘80s and did every conceivable job that one can imagine there. I never actually got into fisticuffs, but I did have a couple of hairy moments, dealing with the convoy. [The convoy was a gang of “ruffians” who harassed the festival.] But I mean, when there were problems, Michael Eavis would say, “Send Rikki out to love-bomb them.”

With the convoy, that nearly led to hand-to-hand combat at one point.

Close. But you know, dealing with the Hells Angels, or whoever it was, I've always found a way of kind of reasoning with people. I think that's probably been a very useful tool in my armory of being able to cool down situations and maybe appeal to people's better nature.

I respect that. Let’s talk about that legendary London pub meeting in 1984 when the principal players in international music came together and decided that the right marketing term for their products was “world music.” Our friend John Collins in Ghana has an interesting take on that. He was at that meeting and felt it was a big mistake. The way he saw it, there was a coalition coming together around the idea of Black music, music that came from Africa or somehow related to Africa and that DJs were playing, you know, Fela and James Brown and Stevie Wonder and juju music all together and kind of making sense of it. After that meeting, there was a sea change. Black music got lumped together with Bulgarian wedding music and Chinese zithers and so on. John said that Black music DJs actually lost work because they they were seen as too limited. What’s your take on all that?

I wasn't at that meeting, but I saw the consequence of it, which was that when you went to HMV or Virgin, any of the big record stores, you found that if you were interested in some stuff other than the pop charts, you had to go down into the basement. And in the basement, there will be a room, and it said on the door, “World Music.” And there you would find your throat singers and all that stuff and you had to wade through that to get to the stuff that you were interested in. So it was marginalization. That was the consequence of this idea of lumping everything together as world music.

I recently spoke with Joe Boyd about his book, And the Roots of Rhythm Remain. He has an interesting defense of that meeting that relates to what you were just saying. His sense is that the World Music tag actually expanded the amount of shelf space available for global music in places like HMV. The fact that that little room existed was actually a huge improvement over what was there before.

Okay, I can accept that. I can accept that. But it was nevertheless marginalization. And in consequence, the kind of coverage that you would get as a world music artist was very limited. You might put out press releases, it might go out to all of the places it ought to go to and the number of people that will pick up on it would be very, very limited.

During those years, I was writing for the Boston Phoenix. I was lucky having been both to Congos, South Africa and Zimbabwe. On the strength of that, the Phoenix funnelled everything my way. This was just at the moment when record companies were starting to release world music and a lot of U.S. editors didn't know what to do with it. I knew a lot about African music by then, and my years at Wesleyan University had introduced me to Indian and Indonesian music, but they were also sending me Balkan gypsy music, Celtic music and all these other things I knew little about.

John also complains that a lot of pretty shallow journalism resulted from the world music grab bag. Writers would read a press release and suddenly be an expert on this or that.

I agree. Fortunately, there were people like Robin Denslow and Gilles Peterson on this side of the Atlantic, who were making waves and giving opportunity to people who otherwise wouldn't have had it. And it was a struggle. I banged my head against a glass ceiling for many years.

No doubt.

Fortunately, one can now see some serious cracks in that edifice. Things are happening. You know, I just got back last week from Womex in Manchester where there were two and a half thousand artists and promoters.

Right. What was that like?

Well, it was good. I saw a bunch of old friends and made a few new ones. I went to the first one 30 years ago in Berlin. But I didn't do any business there, because…What did I have? I had Joujouka, the Pan-African Orchestra from Ghana, Les Ballets Africains, Fela, all these huge orchestras and things I was dealing with. And they'd say, “Haven't you got any trios?” Yeah, yeah. So I didn't do any business, but I had a good time. I went back once to the one that was in Budapest about I think seven or eight years ago. And again, it was a social event for me. I just had a good time, you know.

Yes, it is a fantastic social event.

So the same thing happened last week up in Manchester. I went with my wife. It was great to see Manchester so kicking. The last time I was there, it was pretty dreadful. And now there are venues across the city featuring all these artists from around the world. And at WOMEX, there's two and a half thousand people all making a living from this thing called world music.

And a lot of younger people, The old timers are still there, but I really notice that age demographic changing in the recent WOMEXs I’ve attended. It used to be a lot about record companies. That's kind of over now; it's much more about festivals and bookings now.

Right. The audience is definitely getting younger, which is very encouraging. I check the Fela stats on YouTube, and month after month after month, and year after year, every time I check it's the same: between 700,000 and a million views monthly. Now you could say that's not too much when you consider he has a 50-album catalog. But a million views? That’s something like 18,000 hours of view time, like two years in man-hours, which is impressive. And then when you look at the age, you see that the increasing number of 20 to 35 year-olds has definitely gone up. So that's encouraging. And that would explain why there are people in a hundred cities that are still listening to you guys on Afropop Worldwide.

Let’s hope! I want to go back for a minute to Glastonbury and to the very beginning of it. Tell me, first of all, how did you get involved? You were involved right from the beginning, right?

Right from the beginning. Well, it was a year before the new reincarnation of the Glastonbury Festival in 1981. In 1980, I toured the Master Musicians of Jajouka. I had 35 of them on the road, and we opened the tour in the U.K. on Worthy Farm, where the Glastonbury Festival is held. But it was a concert in front of the wagon shed. And I remember going for a walk with Michael Eavis, the farmer, who told me he had these plans to reinvent the festival and said, “Would you like to join us?” And I said, “Well, I'm kind of busy at the moment, but I'll give that some thought.” Anyway, a year later, there I was. It was a struggle at the beginning, you know, as far as media were concerned.

Did the media ignore you?

Well, not totally. They would come during those first early years, but they only wanted pictures of hippies sliding about in the mud. That was all they were interested in. If the sun was shining, they'd just turn around and go home.

No story here.

No story here. Michael Eavis, the farmer, was a very canny guy. I remember seeing him once calling the meteorological office, asking, “Any sunshine at all?” It was like he was ordering gravel. But slowly, slowly. The thing just built. It was a very interesting experience for me. I never used to go to bed. I was up for a week and I don't do coke or all those things. Just a few good spliffs would keep me going. I don't do alcohol. I never got into that.

You got through all this without drinking. Amazing. Admirable.

Well, I don't know, but, yeah, I've never drunk a beer in my life. I've tasted it, but I never liked it. I was drunk once in my life. I found it such unpleasant experience that I didn't want to do it again.

Well, good for you. I expect that gives you an edge over a lot of people in this business.

It could be the case. It wasn't with that in mind that I didn't drink. But then I discovered weed and I said, “Okay, I'm all right here.”

Well, speaking of people who love weed and don't drink, I have to ask you about Thomas Mapfumo because, as you know, I put a lot of time into working with him and writing a book about him. And you come up at one point in the book, but just briefly. So I'm just curious if you could tell me a little more about your memory of him and what it was like working with him and all that.

Yeah, it was good. I met him when I toured him in the U.K.. We got on very well. I remember a lovely story at the end of the first tour that I did with him. The tour was finished and it was time for them to go. I can't remember exactly what the problem was, but there was a problem with his return tickets to Zimbabwe, him and the band. They couldn't travel, and we were still waiting to get money to settle the books at the end of the tour. I had a girlfriend, an American girlfriend, and we'd had an argument and she'd gone back to America. Then towards the end of the tour, we'd made up on the phone, and she'd come home. So I finished the tour and I'm going home to my apartment to meet my girlfriend. I rang the doorbell and she opened the door and I could see candles lit and everything. And in the corridor behind me, she looked and saw the entire Thomas Mapfumo band. We didn't have anywhere for them to stay or any money to pay for hotels. I think there were a dozen of them, if I remember correctly. There was one even sleeping in the bath.

That’s great.

There’s another lovely Thomas Mapfumo story. Do you know Lou Edmonds?

I do. And I know his story about when he had to step in and play with the band because a guitarist went missing.

Exactly. Funny enough, I bumped into Lou at Womex last week. We hadn't seen each other for years. But working with Thomas was good. I think he lives in Oregon now, isn't it?

Yes. He lives in Oregon now. I consider him one of the giants. Of course, his music has had nowhere near the international resonance of Fela’s. I partly relate that to the fact that it comes from a region of Africa that has virtually no connection with the Atlantic slave trade. So the musical conversation is more complicated. The characteristic rhythms and melodies in Zimbabwean music are less familiar to Western ears than those coming from West and Central Africa where we share the legacy of the slave trade. That's part of it.

That's definitely true. I suppose also the jazz element in Fela music has helped them to reach out to a lot more people.

You know, I saw Seun Kuti this summer with his internationalized current version of the Egypt 80 band. They were sounding great. We had a chance to talk, and he said an interesting thing. I asked him about the way Afrobeat musicians have been sort of marginalized by the new generation of Nigerian pop stars, and he said that this had caused the Kuti family to come together, put rivalries aside and perform together and really work as a unified front, if you will. I thought that was interesting. Is that your experience?

Finally. Yes. Right. I mean, when you look at the Marley phenomenon, the musicians were together, man. They stuck together. And so when I see that kind of solidarity within the Kuti family, I'm very happy to see that. And they have to. I'm seeing more and more references to the music where they're kind of knocking the “S” off these days. They're just calling the music Afrobeat, which is a misnomer. Afrobeats was a marketing ploy. Come on, man! Some DJ came up with it.

Right. The Afrobeat/Afrobeats thing will sew confusion for generations to come.

I'm sure it will. And you know, in Fela’s last years, he abandoned Afrobeat and said, “I'm playing African classical music. And I don't care what you do, Rikki, but don't fuck around with my music. You don't mess with Tchaikovsky, so why are you gonna start on me?” But yes, it will create confusion. Because the music's got nothing to do with Afrobeat per se. At the same time, I quite like some of the music. I'm only irked by what it’s talking about? They're just talking about leg over. It's a leg over story every time.

Yes. I like some of it too, but I tire of it quickly. There’s a lot of repetition. Still, you can’t argue with the success. It's unbelievable.

Yes, it's hitting a nerve in people. It functions. It switches something on that people appreciate and enjoy. I just feel that, particularly today, when you look at Nigeria, man, they are hurting. They are hurting! I mean, when I was last in Nigeria two years ago, it was about 700 naira to the pound. Today it's gone past 2,000, which is just insane. And I'm struggling at the moment trying to get my book out in Nigeria at a price that works for me and for them. It's not easy, not easy at all. I'm about to bring out the e-book version of my book, and I'm about to go into the studio and record the audio version. I'm looking forward to doing it, and I'm going to incorporate music into the book as well.

Great. I just saw your Global Island Discs playlist. There’s a lot there to dig into.

Well, look, you know, the beat goes on, but I'm really happy that I actually took the time and trouble to write this damn thing down, which was really enjoyable. And there was an added payback that when I was thinking about a particular event, I would remember someone, and I'd go and Google the guy. I found myself having these conversations with people I hadn't seen for 60 years, you know? Which is beautiful.

That's lovely, yeah. Are you familiar with this band in Barcelona that's doing Grateful Dead songs in African styles, Afro-dead?

No.

We just did a podcast on that, which you might find interesting. It was spearheaded by Aaron Feder, and American who leads an Afrobeat band out of Barcelona called Alma Afrobeat.

Interesting. I might have heard of them. Have you heard this Brazilian Afrobeat band called Funmilayo?

Yes. An all-women’s band, right?

Yes. Very good band. I'm toying with the idea of putting something together for them.

Well, that was the last thing I want to ask you about. What are you doing now? I'm sure as a compulsive manager, having gotten this book done, you've probably got new things cooking.

Well, I'm not managing anybody at the moment. I'm still CEO of a company called Kalakuta Sunrise, which is a holding company for Knitting Factory Records and Partisan Records. It's a mantle that I wear very lightly because we've got an amazing team of people on both sides of the Atlantic doing extraordinary work.

Lucky you.

I think you know I put out these Fela vinyl box sets

We have the first six, and are eagerly waiting for the seventh one. They're treasures.

And we're about to start work on remixing the entire Fela catalog in Dolby Atmos.

That sounds like fun.

Yeah, that's one of the things that I'm working on at the moment, which is kind of exciting. And other than that, you know, I've kind of been busy promoting this book. The first time in my life that I've ever promoted myself, you know, I've always been busy tooting trumpets for other people.. I have to say, I'm quite enjoying the process. And I get to chat with chaps like you.

Well, it’s a pleasure to speak with you as well. Good luck with the book.

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles