Rokia Traore’s fifth album Beautiful Africa (Nonesuch) is no doubt one of the most innovative and interesting African releases of 2013. Continuing the guitar focus and rock aesthetic of Rokia’s 2008 release Tchamantche, this spare and elegant set of songs was produced by John Parish, of PJ Harvey fame. The sonic textures are rich and subtle, and vary from sublimely intimate to flat-out rocking. Singing in Bambara, French and even some English, Rokia has plenty to say here about musical life, culture, relationships, and Mali’s cataclysmic year of political turmoil in 2012. She has also created a foundation called Pasarelle (gateway) in Mali to provide training and opportunities to young performance artists. With her 7-piece band, she performed a stunning, sold-out show—mostly featuring songs from these two albums—at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theatre on November 15, part of the White Light Festival.

Banning Eyre recently sat down and spoke with this groundbreaking Malian singer, beginning her frank reflections on musical life in Mali these days. Here’s their conversation with photographs of the Lincoln Center show by Kevin Yatarola. Note: an excerpt of this interview appeared in the program notes for Rokia's Lincoln Center concert.

Banning Eyre: Rokia, you told me just now that the situation for artists in Bamako is worse now than it was 10 years ago, and this was true before the political troubles of 2012.

Rokia Traore: It was before the crisis. Let’s just talk about Bamako, because the rest of Mali is worse than Bamako. It's simple. An artist in another city in Mali cannot make a living from music at all. In general, they have no work and just make music casually, and some of them, like balafon players especially, become famous, and come to Bamako and make a career as a professional. But if they get sick for two weeks, or have the sort of problems that you can have in life, that shouldn't be a reason for career to stop, but because you've been sick for two weeks, it does. So there isn't a real economy in Bamako.

I remember in 2003, I organized a strike. It was really a demonstration. Back then, we were still hoping it would be possible to clean the market of pirate products, and sell more regular cassettes and CDs. This way we would make more money for artists from their work. But what I see now, it no longer matters. This is not the purpose anymore. It's simply to find a new way to make a living from music. And the problem is that now, internationally, records don't make sense. They no longer make sense in terms of the economies. Even here. Everybody has seen it. The amount of records you sold 10 years ago now is cut in two.

But in Mali, the option we used to have to make live shows, we don't have it anymore. And that's why I'm saying even before the crisis, before the occupation of the North, there was a very complicated problem there. And I know, for example, one of the ngoni players who has been working with me for 13 years, his way to make some money and save some money, and also have a more comfortable life, is to buy sound equipment, a sound system with speakers and so on, and rent them in Mali. So that worked for five, eight, even ten years. And most of the artists touring abroad used to do that. But now, everybody can make the same thing, buying some stuff from China or Nigeria, which are cheaper. The quality of the sound is not as good. And also, they don't buy the right things. They don't care about that. You just have to make noise, and the audience is happy. Because they're not used to listening to music in good conditions. So it's several things all melded together.

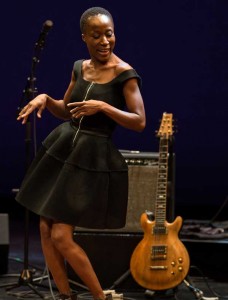

At Rose Theatre (Kevin Yatarola)

At Rose Theatre (Kevin Yatarola)

B.E.: We had a recent report on Afropop from Christopher Kirkley of the website sahelsounds. He was telling us about how people now exchange music via their cell phones, very easily. A lot of these phones can automatically copy songs from one phone to the next, just by putting them side-by-side. This has even undercut the market for pirated cassettes, right?

R.T.: There is no one making albums in Mali anymore. When I made my album, I wanted the guy I used to work with for six years now to just release it in Mali, not for money—because I have and never made a living from my work in Mali. It never happened. Because I'm not a griot. I have never been able to make weddings and things like that. There are not fans giving me billions of CFA. Because I don't sing for people directly. So I think I'm the first person of a new generation, singing in a different way, but also, this is one of the characteristics of this kind of career. You don't make a living from music. Forget it.

B.E.: Even the griots in Mali are complaining now. With curfews and all that, there aren't so many weddings and parties.

R.T.: Yes, now it's more complicated for them. But they can stay there without traveling. If I don't travel, and I stayed in Mali, I would simply not be able to eat. It's simple—because I never make money from music in Mali. But it's important to release the albums there. People know about the music, and they request that. "Why don't we see new music? Have you made a new album? Why don't you release it in Mali?" Since two albums now, I can't find anybody to release it. Because even those who used to produce albums, no longer make money with music. So they stopped. And now, what everybody does, all the artists in Mali, especially those who have a career just in Mali or West Africa, they make two or three songs for rich people, singing for them, and they get houses and cars like that. They send these tracks through phones, and they make a video track for that. And generally, the person that they sang for is the one who financed the video clip.

B.E.: But you can't finance a career on that basis. You can't have an industry on that basis.

R.T.: And you cannot hear good music that way. I'm sorry. We've talked a lot about Mali music during this crisis. And I say, "Well, this is a good thing. Because the rest of the world must be aware of what's happening in Mali. And if you can use music to create these conditions, it's a good thing.” But let's be careful. Before the crisis, music was in a very bad state in Mali. Absolutely. And if we do nothing against that, it's going to continue. I'm sorry. I used to be a fan before becoming a professional musician. I didn't know I would be able to become a professional musician, you know, this is still a dream coming true. When I get on stage and I perform for audience, I love that. But I still continue to listen to the others, and I really love the others’ music.

I know that I cannot be proud of myself and think that, because I know this is something very common with artists. They are very good, and each artist thinks that he is the best, and this creates a kind of situation. I don't want to be in this kind of feeling. It's important to me to listen to the others and continue being aware of who the artists are of the moment. And who is doing something really interesting. And I'm sorry, I didn't feel the same thing I felt when I went to see Habib Koite's shows 10, 13 years ago. I cannot find the same feeling. It no longer exists. There is not anybody who creates now among young Malian artist the same thing.

Oumou [Sangare] was the same. That was amazing seeing her on stage. Not simply her voice, but the way she was dressed, the band, herself. She and her musicians, they exist to be on stage performing. But I'm talking about 10, 13 years ago. Now, it's very difficult. Because what I'm remembering is shows in the French Cultural Center. Even then, there were no other places in Bamako where you could go and listen to music in good conditions, and when I say good conditions, I'm not talking about very expensive sound system. The one in the French Cultural Center was simply okay. And they used to hire a sound engineer to take care of it. That's the only difference. It was nothing expensive. Nothing impossible for Malians to have in other places in Bamako. But even in the French Cultural Center, that no longer exists.

B.E.: Really? Those concerts have stopped?

R.T.: Because the budget has been reduced. And they cannot work in the same conditions that they did 10 or 15 years ago. When I performed there, before, or when I went there to see Ali [Farka Toure] performing or Oumou, or the Symmetric Orchestra, with Toumani, Bassekou, and Keletigui. Those who had a chance to attend of those shows, they must know that they were lucky. Now Keletigui is dead. And Toumani and Bassekou are doing other things, which are also good. But the conditions are not the same.

I remember Jacques Zale used to pay artists for their work. He used to pay fees. He could, because he had a budget for that. The last performances I did at the French Cultural Center, I had to wait until we saw how many tickets sold and see if there was a profit. And then we would share the profit. And I could do that, because I have a career in Europe and in Western countries. I can move money. I can even invest in a foundation to make these kinds of things exist, and have a venue, and everything. But what about artists who are living in Mali?

B.E.: Yeah. Young artists. Or even veteran artists who don't have things going on the outside.

R.T.: They will continue making one song, two songs, three songs for some rich person. And singing the way these people would like them to sing, with no possibility to experience other ways of making music, or simply enhance their artistic abilities. Yes, there is no budget for that. And the Malian Minister of Culture did not have a budget for that 10 or 15 years ago. Now, it's not going to be better.

Even now, I think the last five years, the European Union has decided to support culture and recognize that it was an important element for development in Africa. So that was a very good thing for Mali. I think it was 5 billion CFA that we were supposed to have over five years. So that was to permit us to create some shows in a place. The name was Blomba.

B.E.: I never heard of that.

R.T.: It was a very good idea. But how to maintain it and make it exist without subsidies was a problem. And they stopped it after the crisis came. Two weeks after the crisis started, it was over. So I can tell you about that for hours. Nothing is done. Nothing is as beautiful as you could think it is when you hear about Malian artists touring. We are just a few of us having international careers. And in what conditions, by comparison with jazz music, pop music, and European classical music? We are the lowest, not in our artistic level, but in terms of comfort, budget. It's the lowest economically.

B.E.: And you are the lucky ones.

R.T.: Absolutely.

B.E.: You are right. A lot of people think that Malian musicians are doing very well. And that's not really the case, is it?

R.T.: And we must say it. We must say it. And we must talk about it. And clarify things. Yes, probably in comparison with other artists in Africa, we are doing well. And also, I think the most important thing is that we are able to create, especially during this crisis—artists did a lot, showing the right image of Mali and making the balance with what you could see on the news. So that was very important.

B.E.: Right. There's been some powerful stuff, like that video with Fatoumata Diawara and all those other artists.

R.T.: Absolutely. But, there is still a lot to do. Yes, music in Mali is going to -- I don't know -- if we don't find solutions, that doesn't mean having big budgets to make things in Mali. No. I think it's also sociological, to understand how the audience wants music to be, and how they want to get music.

B.E.: Wow. So much to unpack there. But I want to get to talking about you, and your record. Let me go back to your past. You represent a new approach to music for Mali in terms of the way you put songs together and the things you say. Tell me what that has to do with the life that you had of coming of age in other countries.

R.T.: I think everything is related to the way I grew up. And yes, Mali has always been very important to me because my parents kept connected to their original culture. They are not from Bamako. They are from a village where, especially my dad, has a very strong identity, because he is one of those who created this part of Bambara. The Beledougou region, it's more than an area. It's bigger than a village, even than a city. But yes, they are those who created this place with a very strong identity and specific rules for behavior. You are not supposed to do some things because you are not like just anybody. You are a Traore from the tribe of Zambla. So it's something very important, and they have this very strong identity. They are proud.

There’s a difference between a griot and, let's say a noble—but that's not exactly the right word. It’s not the same idea of nobility like in India or Europe. For example, a noble must not speak to an audience. You must have a griot for this. So it's not your words. What you say is very important, and you are not allowed to mistake. That's the difference between a noble and griot. A griot can say, "I mistook." And the audience can understand, a village can understand, a city can understand. Okay, he's a griot. He can. But nobles used to be also came to us and emperors and chiefs, so they are not allowed to mistake. The people must see them as perfect people. It’s as in politics, or monarchies. It's exactly the same thing.

So this is my dad's origins. And even though he left the village to go to Bamako for his studies, and then he came back to the village and taught there, French and history and geography, for years. And he had his first three children in the village, and then left to study again. And I was born in the city not far from Bamako, but not far from the center of Bambara.

B.E.: Which city?

R.T.: Kati, which has the military camps. But it's also closer to this part of Mali, Beledougou. So I was born there, and I left when I was three years old because my father started working as a diplomat. So it's like they left the village and all this firm identity to go directly to Europe, but not for migration as we used to know it for Africans are Malians. But for work, so they could go back and forth. And I kept connected through them. But at the same time, I could tell that I am not seen like the others. First, we used to come back for holidays, and when I played with my cousins and all the relatives, I could see that I am different. They say some things I don't understand, because learning Bambara and French at the same time, and living in a country where I speak more French, and peoples between more in French than Bambara, so each time when I came back, that took time before I understood what people were saying. Also what were the things to do, the right behavior to have.

And I learned. But you know, living that way, people always show you that you are not from there. I don't think it's nasty; it's what it is. You are coming back. We are speaking too fast Bambara, so yes, you have to take time to understand. They will explain to you, but they know that you are not from there. And then when you go back to Europe, you know you are not from there. Because also the time, especially when you're a child, spending time in the country, even if it's just a month or two months for holidays, when you go back to school in Europe, that takes time before you get back into French and into things as they must be down there.

So music eventually for me was a way to be Malian my way. And all my life is about that. It's got to be. Because what you know, you know it. What you experienced, you experienced it. Where you traveled, what you've seen, it's part of you. You can't come back home and pretend you forget everything. You know new smells and new tastes and new... I don't know. Yes, I grew up that way, traveling all the time. So I'm someone different everywhere.

In the childhood and teenage years, it is horrible. Because you want to feel like you fit in somewhere, and also the others are so nasty at this stage, and they show you that you are not from there. And then, when you get older, you simply understand that you are crazy lucky. It's a chance. But the challenge is how to do you your way, to be yourself, as a Malian, as a European, as a singer, as a mother, as a wife, but your way. Because it will never be a Malian way, or a French way, or a Belgian way. These are the two countries where I spent most of my childhood—Belgian first, and France when I started working. I stayed there for 10 years. I like it now, but I know. I'm self-conscious about that. I have a very good relationship with Malian musicians, but I don't have a common story with them.

B.E.: It took time for you to earn those relationships, didn't it. That didn't happen right away. I remember the beginning of your career, when you were working with my friend Barou Diallo on your first record. So I've watched your career, and it's always so interesting to see the trajectory. You are always reaching higher, trying to do something different, something new. And it goes perfectly along with what you're saying. Because you've really had to work to inhabit this identity your way, as you say.

R.T.: It's easy for me to do something new. Because for you it's new, for me, it's not. I just take something European and something Mali and putting them together, because I feel so comfortable in both. That's what I'm saying. Now I know that it's an advantage and not something negative. Because when I say it's easy, it's more than that. It's great. Because I learned from that. For example, last time I had this great experience through my profession was when I started studying the Malinke classical griot singing with Backo Dagnon.

B.E.: Oh, yes. I was going to ask you about that. She is amazing.

R.T.: She is. When we talk about griots, everyone knows griots. But the thing to know

is that all griots are not the same. Most griots are more modern than pop singers. There are some old griots. Backo Dagnon is not that old. She's probably 60 or 62. But she is rooted in the real griot tradition, and she defends that. She fights for that. Young griots don't like her because of things she says. She said that if a griot puts on more expensive clothes than the noble he or she is going to sing for, or is supposed to serve, there is a problem. Because a griot must be humble. And never lie. Never sing the wrong things. You have to sing for a noble who deserves that.

B.E.: You don't just flatter a lot of people.

R.T.: Absolutely. And you don't sing things that are not true. You cannot sing that a drug seller is a great man just to get some money from him. So, of course, you can imagine that Backo is not loved, not appreciated at all. Because this is the opposite of what griotism became.

B.E.: So there really is a lot of that kind of shallow or dishonest flattery, you would say.

R.T.: Yes. And Backo Dagnon really is someone special. And very strong, and she doesn't care. When she's doing a TV show, she says all these things. And the last time I remember, she did a TV show and she was really well dressed, and she said, "You know, I never wear something so expensive. It's a noble who takes care of me who gave me that." And she said the name of the woman, and said very great things about her and thanked her, "because without her, I don't have the resources to get such a thing." Which is not true. She's a very strong woman. I know what she does for her sons and everybody. She has to work and make money. But she's extremely humble, and also a great singer.

B.E.: I remember hearing her sing in about 1992. It was one of those concerts in a stadium with a lot of different artists, and she got up and sang “Sunjata,” and it just knocked me out. I had never heard of her.

R.T.: She's great. She is great. And it's not just about power. It's about melody, the way she is able to phrase and sometimes, I can just hear something really classical or jazzy about melody, and how to make the sound the deepest possible, and the strongest possible, without screaming. She's amazing. I'm still learning with her, because I wanted to learn the traditional way, which means to learn from Backo Dagnon.

You cannot buy her. It's not about money. It's not about how famous you are. She doesn't care. It's about respect. And she taught me, "You know, Rokia, why I like you. You're like my daughter." I'm so proud of that. Because myself, to learn, I was able to come to someone's place, and clean everything, and do everything the person wanted, and wait until the person wanted to talk to me and sing a couple of songs I can listen to and understand the way the song is done. And she said this is the way griot school must be.

B.E.: That's wonderful. How long have you been working with her?

R.T.: I started three years ago. I met her first to ask her if I could cover one of her songs. It's not actually hers, it's a classical song, but her version is the most famous. "Titati." She made the best version and I wanted to cover it, not myself directly, but with the youngsters we work with in my foundation. So it's a project I created with them. We have never performed in the US yet, because I don't want to create a confusion. This project is very different from my own project, and I don't have a career as established here as it is in Europe. So we've never performed here with the 10 youngsters that we work with in the foundation. It's an opportunity for them to work, make money, and also working professional conditions. We cover songs from Backo Dagnon, Tata Bambo, Super Biton National, Ami Koita, Oumou, Abdoulaye Diabate, but also from Tabu Ley Rochereau from Congo, from Bob Marley, Jacques Brel...

B.E.: Is this one of the three projects that you did in Paris last year. Donguili?

R.T.: Yes. Donguili. And Donguili was the first time for me to ask Backo if I could cover her song. And she was surprised. She said, "In general, young people take the songs and they never ask." So I was asking. I said I'm not going to make an album with it but I want to explain to you the project, and if you could come to the show and see what we did with your song, that would be great. So she was there. And Tata Bambo was there. Oumou couldn't be there; she came late, too late. Ami Koita was there. And it was great. That was the first contact with Backo, and then later I asked her if she could teach me a couple of songs for Damu, which is a tale I wrote about the Mande epic, and I needed Mande epic songs, and I didn't know that. So you know that's great.

B.E.: And I read that that project was inspired by the work you did with Peter Sellars and Toni Morrison, Desdemona. I saw that production. It was powerful, fascinating.

R.T.: Yes.

B.E.: Tell me this, though. Now that you have this relationship with Backo, what does she think about your music?

R.T.: I have never asked her.

B.E.: Really?

R.T.: Because it's about her. I have things to learn from her, and I don't care. I never give her what I do. Because when I spend time with her, I record everything she says, because she sings me the melody and also tells me that the story of the song and everything, so this is so interesting. It's because of who I am that I could do that. Because I speak fluent Bambara, and I know how much you must respect older people if you want to get anything positive from them.

B.E.: I've been listening to this album for a while, and it's amazing to me how many different colors you have in your voice, from very soft to very strident sounds. You have a broad palette of vocal sounds. And I'm wondering. When you write a song, are you conscious about planning that, that you're going you use certain sounds, or does it just happen?

R.T.: I think making an album or a song is a process in at least three different steps. First you write a lyric, or you compose the music and then write a lyric, and then you have to put them together. Each step is different. When you're writing, it's about technique—why do you need a break there, and how do you get out of the break, or into the break? Once I write everything and I play everything to try to sing the lyric and play the music, the way I've done it for 13 years now is to involve Mamah Diabate, the ngoni player I work with. We start working, the two of us. Last time, we also worked after a week of working with Mamah, two of the young singers I taught joined us. They used to sing with it, but it was about singing technique, the European way. That's one of the projects we have in the foundation with youngsters. Two of them recorded the new album with me, and they tour with me now, and they've been involved since the beginning of the album.

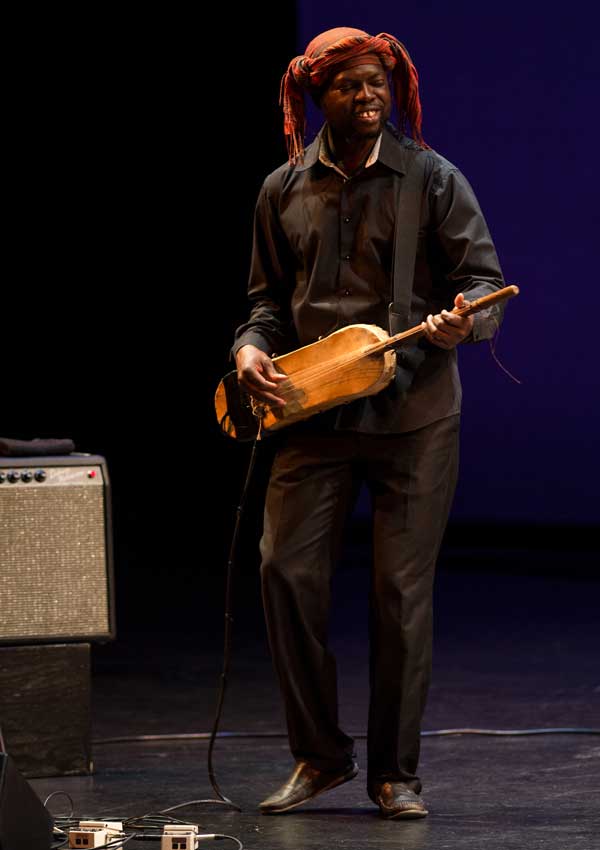

Mamah Diabate (Kevin Yatarola)

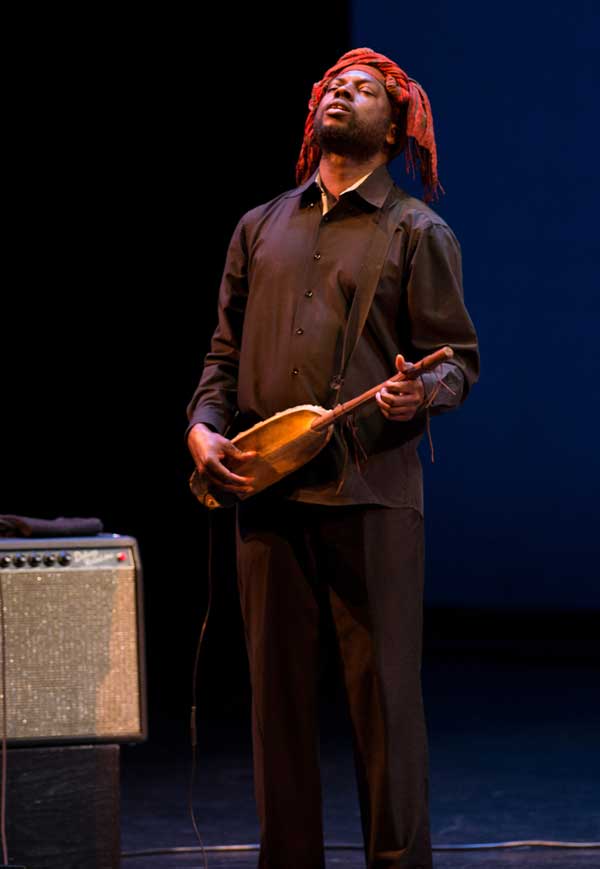

Mamah Diabate (Kevin Yatarola)

Then, after two weeks working with everybody, the song starts to exist for me, and I start singing. And it's not like I write songs thinking of what is good. But in terms of vocal technique, once the song exists, it's for me to follow the song and make it mine and sing on it as if someone else wrote it for me. So that's the most interesting thing, because I love singing, and once I start singing, I feel free, and I feel pleasure in phrasing and finding new ideas, and also pleasure in experiencing new things. Because once I know how to do something, it's no longer interesting. I have to find something new. Maybe that also makes each album different. But it's very natural.

B.E.: So that shaping of vocal textures comes later. For example on the song "Beautiful Africa" when you sing in English, this very different voice comes out, this very strong voice. I know that sound from other songs, but it's a really striking moment on this record. Was that something that just came late in the process?

R.T.: Yes. "Beautiful Africa is" was a difficult song. It was the last one, and the only one that has a direct connection to the troubles in Mali. And I wanted it in these three different languages, just to make sure that the most people possible will be able to understand my anger, and also... it wasn't about sadness, but how I continue trusting in this country when everybody and everything shows that it's lost. I wanted to trust in it, and I wanted to be strong enough to push others to trust in it. Now I can speak about it. But when I wrote the song, it was one of the songs I wrote the quickest, but also the most difficult. It was a very natural thing. I didn't want to find a specific way to express, but just to say it as it was coming from my heart. Then I had to sing it. And that was difficult.

How to sing these different lyrics and three different languages? And using this melody I composed. Yes, I've been trying to find a way before getting in the studio, and eventually I was so tired I thought, "Well, if we cannot record it, it's not a problem anyhow." But when I got in the studio, I found the way. I don't know how. Every part, every specific language came to me as it must. It's not easy to describe, but as I said, it's about how much I love singing. I really love singing. That's why I'm singing.

But it’s not easy for me to consider myself as a singer, because I feel like I'm always learning. And there are always interesting things to learn. I have a lot to learn and classical singing, jazz singing, traditional singing, even Malian singing. I'm learning so much with Backo Dagnon, and I'm planning to start learning with other traditional singers. So yes, that's a great thing.

B.E.: That song has a complex message. Right after the crisis, there were a lot of songs saying essentially, "We want peace." That's good, but it's kind of easy, right? You are expressing something more complex, this pain and angst, but at the same time, love and faith.

R.T.: That's one more way that I'm different. Some of those singers, Malian singers, their singing tradition is about singing what you wish, simply. But for me, that was difficult. Yes, I want peace, but peace will not come from the sky like rain. We have to build it, and if we are not able to understand how it's possible, considering what's happened. I don't know where peace will come from. Even though it's complicated but this French intervention, and from Chad also. We need his help, but at the same time, it doesn't simplify the economic and political situation.

I've been invited by many artists to sing, because there are so many versions of peace songs about the crisis in Mali. It's unbelievable. And I've been escaping all the time, because I cannot sing when I don't trust it. For me singing is not about politics. It's not about what you must do, because everybody's doing something. Probably it's not intelligent on my part to do this, but it must come from my heart. So when I wrote this, I wanted the album to be called Beautiful Africa, and the title of the song is "Beautiful Africa." But at a certain moment, before the album was coming out, I wondered if I am not going to change it, because I didn't want to use in any way the situation in Mali for my album's promotion. It was sincere; I wanted to sing about this complicated situation.

B.E.: It comes across that way. And not all the others things do.

R.T.: That's what the record company said to me, that I was not using Mali at all. That was very important to me. These are things that most Malians don't want to hear now. Because we don't want to recognize our personal responsibility in what happened. And for me, this is the most important thing. Yes, what's going on now, it's going on. But the future of Mali depends on our ability to manage this very complex situation. And we have also to accept that there was no better solution. We have been mistaking that for years, making the wrong choices for years, and we can say a lot about the responsibility of Western countries. But Mali is ours.

And that's what I said when a French journalist asked me, when Francois Hollande was supporting elections in Mali in July. And the guy said, "Francois Hollande is going to force some elections in Mali in July" I said, "Wait. Francois Holland--maybe for you and international opinion is someone important for what is happening in Mali. But for 80, or I think it's 90% of Malians, he is nobody.” And that was a pity too. Because I think this government we had in Mali to manage the situation during the occupation, and until now, they were simply amazing. We have to recognize that politically, and in terms of diplomacy, they have been crazy good.

B.E.: Mali’s interim president, Diancounda Traore?

R.T.: Yes, people initially didn't want him at all, but eventually he did a very good job. He had a very good government. We had a very good ministry of foreign affairs, a very good minister of justice. At least these two. And you could see what they were trying to do in a country where nobody trusted him. So they were working, and also the other political parties were trying to... Maybe that's called democracy, but it was difficult to understand. But the government did a great job. So we will see now. Maybe we're gonna discover some bad things that they did, but anyhow, I know the pressure that was going on in Mali between the Army and some very powerful religious leaders. And what they wanted was not a French intervention. And it wasn't clear at all. I sometimes couldn't understand, even me as a Malian, that some people were wishing that the extremists would come to the South.

So I don't think they realized what they wanted. It was crazy. Because we've never had such a situation in Mali. So they were playing with fire with no idea of the consequences. And there were some political parties which probably never would be powerful and never would have even, I don't know, 10% of the vote. They saw in the situation a way to get more important, and they started using all kinds of things, including their relationships with European journalists, so it was a complicated situation. And that's what I sadi to this French journalist. I definitely respect Francois Hollande as a French citizen, but in Mali…

B.E.: What about the moment when he sent in French troops? Do you think had to do that?

R.T.: Of course. That's why I say Francois Hollande is supporting elections in July. That doesn't mean he is obliging people to do elections. We cannot wait to have elections. Beside all the things we are talking about, education in the North and so on, we needed these elections. And it went very well. There's one thing clear. Keita was the one Malians wanted. They have him now. Now let's see what he's going to do. But probably, in terms of democracy, that's the clearest and best election we've ever had in Mali.

B.E.: That's interesting. For me, this has all been an experience of having the layers of illusion peeled away one by one. I was so unprepared for what happened in Mali last year. I was out of touch. So it’s been a painful, complicated education. But let's shift to a more personal focus. Because last year, 2012, was a terrible year in the history of Mali, but it was a great year for your career.

R.T.: You think so?

B.E.: Well, I'm just reading your biography here, these three big concerts in London, all with different themes and music. Then creating this record. The Desdemona tour. It looks to me like you were having a lot of success last year, but at the same time you were going through a very painful experience with Mali. Did you feel that contradiction?

R.T.: I don't know. Maybe I still don't realize my success. It's like you're in the middle of a storm and are trying to hold onto everything you can. I decided to move back to Mali about five years ago, and I've lived there for the last four years. The reason I wanted to move back to Mali was for me. Because I like it there, and my parents are there now, and they're getting older, and I wanted my son to spend some time there with everybody and grow up between the two continents as I did myself. It didn't have to do with patriotism or anything like that. I simply wanted to move back to Bamako. And I wanted to create this foundation because I have my ideas concerning the music economy in Mali, and even though I cannot do everything, I think I can bring a contribution. So I started this project, and then problems started.

The simple fact of having a foundation without being rich is something. I'm not rich. And some people told me, "You're crazy. You know how expensive the foundation is?" Yes, but I had bought by chance this big piece of land. It's a big house, and I didn’t want it for just me, so I decided to build the office of the foundation there.

B.E.: This is right in Bamako?

R.T.: In Bamako. And I would like to have an outdoor stage, and record music here, and give the opportunity to artists come here and perform, and sell tickets at a very low price. All that was already a challenge.

B.E.: So this is the idea of your foundation, Pasarelle. What does that mean, by the way?

R.T.: Pasarelle is a gateway. So all these things were already a challenge. And I'm a mother at the same time. I have to take care of my son. He's seven now. When this problem happened, like you say, me too, I couldn't imagine that something like that would happen in Mali. When it happened, I went to Air France to check-in. You know you can check in your luggage downtown and just go with your boarding pass in the night. So I did that. I left my luggage. And when I was going home, I heard gunshots. For a couple of weeks we've been having very violent demonstrations, Army soldiers who didn't want to go to the North because they're not well paid and not well trained in things like that. So I thought it was something like that. And I went home, and someone called me from France and said, "You know that Air France is not going to leave Bamako tonight?" And I said, “Why? They didn't say that. I checked in.” And this person said, "Wait. Listen to me. You don't know that there is a coup d'état in Bamako." And then all my phones started ringing at the same time. We never left this Wednesday. We stayed there, and all the nights, we could hear guns. And my son was saying, "What's going on, mom? We have to leave."

And once I said, "These are soldiers. And there's a coup d'état." And he was like, "Wow, the Army is coming into our place. They're going to destroy everything. We should leave." And we stayed there for two weeks in this situation. Everything closed. All consulates. The airport. And all the youngsters from the foundation coming to me, and coming as soon as they could, because there were small battles everywhere in the city, and sometimes they came in just asked me, "What are we going to do? What about our projects? Are we going to travel with you in London or not? Are we going to cancel everything?” And my parents are calling me and everybody. And I thought: I cannot take such a responsibility. Why did I create this foundation? This is too much. I should stay in France and use my money in a big house somewhere in the South. That would be better.

Eventually, after a couple of days come you think, well, let's keep calm and find solutions. And in the end, we made the album, and did the projects with the Barbican Center.

B.E.: So you made the album after all this?

R.T.: Yes. I finished the first part of rehearsals with Mamah the ngoni player and the two girls, and myself on guitar. And Alou, who used to play calabash with me and left with Bassekou's brother to make his band, is now working with me again, but for the foundation. I also work with him when I'm composing. He plays all the drum parts. So we had been rehearsing for three weeks, and we finished there thinking we're going to go with the choir and the foundation for these gigs in Italy, and come back and continue rehearsals on my three projects-- Donguili, Donke, and Damou [Sing – Dance – Dream]. So everything started there. Then we had to move all the rehearsals to France.

Fortunately, we had enough money in the foundation to pay tickets for all the youngsters who already had their visas. Those who didn't have visas couldn't come. So there were decisions to make. I think I didn't have time to sit down and think about whether I was successful or not. If you had told me I would be able to not be crazy in such a situation, I wouldn't have believed it.

B.E.: So you found strength in yourself.

R.T.: Yes, and also, you just get older and feel life in a different way. I learned a lot. I was close to people in Ivory Coast when trouble happened there, and I was really sad for them. But I couldn't imagine that a deeper sadness was possible. Because when you are inside of it, and it's not simply about what you see happening to people around you, but also what you can do, and you feel yourself all the time responsible. It's horrible.

B.E.: Let's talk about the record itself. I notice you haven't done the thing that so many Malian artists are doing these days, which is inviting a lot of guest stars to be on the CD. Was that a conscious choice? And do you ever get any pressure from the record company to do things like that?

R.T.: I think people I work with know that I can't stand pressure. I don't like that. So they don't try. I used to invite people, Kar Kar, Ousmane Sacko. And I'm very proud of and glad about the songs. Especially the one with Ousmane Sacko, because for me, he's one of the most beautiful voices of the world, and I wanted to have him on an album and work with him and compose for him and produce his album, and then find someone to help him, a record company. Ousmane Sacko sang on Bomboi, on "Mariama."

So well I do it, I do it because it must be natural. When I worked with the Kronos Quartet, it made sense to me. I wanted it. I think they are probably the best string quartet in the world. And when I sing with them on stage, it's simply amazing. I can make a mistake, I can do anything I want, and they are there, backing me. That's great. And I would like to work with them again in the future. So there are artists that are really a pleasure to work with.

B.E.: It has to come from you.

R.T.: It can come from them. When I did this song with the rappers from Senegal, Dara J, they were the ones who invited me. I listened to their music, and I said, “Okay great. I would like to sing with you.” And we did it. So I do it, but probably not as often as other artists. And for me, it mustn't be about who'll be able to sell more.

B.E.: Right. Put a sticker on the CD and sell more copies.

R.T.: In general, I really appreciate the people I know, for example John Paul Jones, someone I met during Africa Express, is someone who I really discovered step-by-step, by meeting his wife, etc. He's someone I really appreciate. I respect him so much that I don't want to invite him on an album just to sell more. Also, it's about human feeling. It's not simply about calculation. But the idea of collaboration, I think it's great.

B.E.: I agree. I'm just noting that it's becoming a trend now, not just in Malian music, everything.

R.T.: Me too. I don't know why they overdo it. To some people, it can appear like I'm proud. I think my music is enough. No, it's not that. For me, business is business. I can be a businesswoman. But there are limits. The human, personal relationships must be based on honesty. I don't like using all these relationships. For example, John Parrish, when I worked with him, it was clear. I needed someone who could bring me a rock 'n roll sound I am not able to do myself, because it's not my culture. And after listening to his own music, and also his work with PJ Harvey, yes, I thought he's the one who would be up to bring me what I'm thinking of, without doing exactly the same as what I heard.

B.E.: So you reached out to him.

R.T.: Yeah. I was introduced to him by Thomas Weil, who gave me albums by three different possible producers. And John was the one I wanted to meet. And of course I wasn't sure at all that he was going to accept. But he did. And he's great. Artistically, but also humanly. He's a big guy.

B.E.: When you started thinking about this record, before all the troubles in Mali and what became the title song, what was the idea?

R.T.: I had a clear idea of making something simpler. In terms of composition, I didn't want it as complicated as, for example, Wanita or Bomboi are musically. In terms of arrangements, these albums were, yes, a laboratory and experiencing things. I don't know, also maybe due to my old age, I no longer wish to prove things to myself by doing all these complicated things; it's also to try myself and see what will be the result. And yes, after four albums and a 15-year career, that's one of the things you know about the most: that you have a lot to learn. But you also know enough to be self-confident and to know what you can get if you try this or this together. So I wanted to make a simpler sound.

B.E.: At the same time, you wanted this more rock 'n roll aspect.

R.T.: Do you know? If you listen to a song like "Kouma" which is one of the songs that sounds to people the most rock 'n roll, it's simply the music of my region. You know, when you go to Beledougou before arriving in Nara, and Nyoro and Mauritania, the sound goes low, and they dance like birds. It's that, and it's also a mix of poems written around Mopti. So it's these things mixed together, and I wanted to try that with rock 'n roll, because I can hear something rock 'n roll in this music.

B.E.: And that's no accident. We know that some of rock n roll's roots like in Mali.

R.T.: Absolutely. And then all that with John's choice of amplifier, and his choice of technology. You know, he is a kind of minimalist, but using just what's essential. That doesn't mean like not using anything, but just what he needs. And it can be noisy, or it can be very calm, but you simply feel when you're listing to it, "That's what I need. I don't need more than that." So that's John.

Yes, all that together, and I wanted something light. That's also why it was a good thing to work with Alou on the calabash on this album, because we understand each other very easily. We've been working together for eight years. So, yes, it's creating the rhythms with him before working with the drums. That was a good thing.

B.E.: I want to ask about some of the lyrics. You talked earlier about the fact that you're not a griot, and that you had this very unique experience of becoming a musician. I love the way you deal with that in this song "Sikey."

R.T.: It's funny. That's a new thing for me. I wanted to try to write funny things, things I wouldn't normally sing about. Because in my education, even if you don't agree with your parents when you're young, what they tell you, all these things come to you later. And you look like what they wanted, eventually. So it's not a good thing in my education to be complaining about your faults. Yes, bad things are said about everybody. Life is what it is. You think bad things of the other, they think bad things of you. And you have to deal with that. And if you are clear with yourself and honest with yourself and know what you want, what the others say it's not important.

So for these reasons, I would have never written such a song in the past. I knew what people thought of me. But it wasn't really important. After 15 years, I'm still not a griot, I'm still not a singer from Wassoulou, I'm still not a pop music star. But I'm still here. I'm still here having a career as a professional musician, and that's great. I would like to write and say, “Yes, music is a choice. It's not because I wasn't successful at school.” Even now, I could do plenty of different kinds of work and make a living from that. Music is a choice. I wasn't born as a griot. I wasn't born as any other kind of traditional singer. I was born as the daughter of civil servants who are expecting their children to start at a high degree and then become high-level civil servants themselves.

This is my choice, but this is also what my parents taught me: always do what you feel you want to do. And singing is my choice. I'm so glad to get on stage and perform. To be on stage, and having an audience in front of me is my destiny, and I'm glad about that. For a lot of people, I'm not the correct daughter of a civil servant. That was one of my problems, not the traditional area, but the Malian modern area. My parents were criticized because they missed their daughter's education.

B.E.: Because you didn't become a professional or a civil servant?

R.T.: And I wanted to stop my studies in Belgium to go back to Mali and make music, without any training in music. And they were thinking, "She's crazy. How can you let her do so?" And my parents said, "We cannot do anything against that. We tried to convince her. She wants to try. And we know her. She wants to try, we have to let her try." And I tried. And now, it's so amazing, people are pushing their children after their studies to become a musician. So I also opened a new way of making music for some young people.

And I can also see that through my foundation, because you make announcement for radio stations and TV to invite young people to apply for auditions, register for auditions. Most of these youngsters probably came because it was me. Most of them have finished high school and started with music after high school. And most of the young girls asked me to offer them a guitar. And I have to push them and say, "There are other instruments. Which one would you like to play? Don't do exactly like me."

B.E.: Too bad there's not a very good business environment waiting for them in the realm of professional music. But thank you. This has been great.