Saha Gnawa joins a long list of ensembles that offer a fresh take on the renowned healing musical tradition of Morocco and Algeria. Gnawa music, with its loping, cyclic grooves and pentatonic scales, lends itself easily to “fusions” with Western music. Artists like Hassan Hakmoun, Kateb Amazight of Gnawa Diffusion, and, more recently, Guedra Guedra, to name just a few of many examples. Anyone who has followed the Essaouira Gnawa and World Music Festival will know that jazz, rock, reggae and hip-hop fusions with Gnawa music abound in Morocco, and around the world. For all that, Saha Gnawa brings something new to the table.

At the group’s core are traditional practitioners Maâlem Hassan Ben Jaafer of Fes and Amino Belyamani, both veterans of the New York-based Gnawa ensemble Innov Gnawa. Saha Gnawa group emerged from freeform Brooklyn jam sessions hosted by drummer Daniel Freedman. Eventually, Freedman organized the jammers into a formal band dedicated to the idea of staying close to Gnawa tradition, not superimposing foreign influences, however harmonious, but adding new dimensions to the music. On the band’s eight-track eponymous debut album, we find guests like Nils Cline (of Wilco fame) and jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin, but their contributions are subtle—no big solos or grandstanding.

The resulting album revolves around traditional Gnawa ceremonial pieces, but while the group’s innovations are understated and respectful, they can also be bold, as on “Tbal,” where Abraham Rodriquez Jr. and Gilmar Gomes conjure an unlikely but surprisingly natural conversation between Gnawa and Afro-Latin rhythms. The album flows like a nighttime ceremony, with ebbs and flows, ecstatic highs (“Baba Hamou”) and contemplative atmospheric moments (“Hamdouchia”).

Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Freedman by Zoom in New York to discuss the group and the album. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Daniel, it’s good to meet you. I’m really enjoying this album.

Daniel Freedman: Thank you.

I've been listening to Gnawa music for a long time and have heard all sorts of takes on the genre. It’s eminently “fusible” music, isn't it?

Yeah, it definitely lends itself to collaboration.

Tell me a bit about yourself and what led you to this project.

I grew up in New York City. My father's a jazz musician; my uncle is a guitar player; so grew up around a lot of music. I was lucky enough to be around a lot of the great guys, Max Roach and Billy Higgins… My father introduced me to Art Blakey, Jimmy Cobb and all these great, great drummers. I got to see Elvin (Jones) a lot, and I wound up studying with Max, as well as Vernel Fournier from New Orleans, Ahmad Jamal’s drummer.

I think it was around ’93 that Randy Weston brought some great Gnawa musicians to town. And I went with Jason Lindner, who's playing keys with the band now. We were actually roommates at the time; we went to high school together. So we went to see Randy, and we saw Gnawa music and had a huge, huge impact on us, a really mind-blowing, spiritual kind of experience.

Since then, my musical life has been a lot of different things. But I definitely grew up in the era before you could go on YouTube and learn things. So I spent a lot of time traveling to learn. In the ‘90s, I went to Mali and Senegal and made several trips to Cuba, and Brazil, also Egypt and Morocco.

A lot of effort, but definitely better than YouTube.

I would up playing with some Moroccan musicians in Jerusalem. Actually, there's a whole world of Moroccan culture there. There was one guy we wound up playing with a lot, Nino Biton, Nino El Magrebi, they call him. Super bad dude. He knew like every song from the whole Magreb. And he was really old school teacher, yelling at you till you got it right, grabbing the instrument out of your hand if you didn't do it right. So I definitely learned a lot from that.

Jason was with us at one point as well. We went on tour and wound up doing a record with this guy. There are a lot of different styles from Morocco, I'm sure you know, but it's really difficult for most people to find a way in, especially the chaabi rhythm. It's kind of counterintuitive for Western minds. The bass drum is not on the one, so if no one's clapping the one, you would think the bass drum is the downbeat. I spent some months in Marrakech and that really helped solidify some things.

I’ve been there, learning music in Mali and especially Zimbabwe, where there’s a lot of polyrhythmic music.

Yeah. I was in Mali and I played weddings often, and I’d be playing the right part, but I didn’t know where the one is.

What were you playing?

Mostly djembe. Some dundun. I’d be, like, I know that I'm wrong. And I see everyone dancing and I’d try to get myself into the right spot.

I also played a lot of weddings in Mali, but they were the more string music weddings with ngonis and balafons and guitars.

Oh, that's the best, man. I got to see a lot of that. I was there in ‘97.

Interesting, I was there in ’95 and ‘96, just before you. But I’ve been back. I keep close ties with a number of Malian musicians.

Well, I would love to go back. I know it's really hard there right now. In ’97, I stayed in Ntomikorobougou where Toumani [Diabaté] had his club.

Le Hogon.

Yeah. Man, I got to play with Toumani and hang. He would play every night at this kind of destroyed building.

Yes, I remember that. His nightime hangout. It was a place that was under construction.

There was nothing there, and this guy would make a fire and Toumani would play. It was unbelievable, private concerts with Toumani all night long.

Well, you must listen to our podcast celebrating Toumani, bound to bring back memories. Also check out our program on Randy Weston. Randy was a good friend of our show. Anyway, I get the picture. You come from a serious pedigree.

I was also in Angelique Kidjo's band for many years.

Wow. I'm sure that was a lot of fun.

It was.

Let’s get back to Saha Gnawa. How did it come about?

I made a record in 2017, before I went on tour with David Byrne. I wound up playing with a few guys from Innov Gnawa, and that's strictly pure Gnawa, with Maâlem Hassan Ben Jaafer. It’s amazing that he's here because he’s a real maâlem, a master. I don't think there's anyone else in America. I’ve heard there's somebody on the West Coast who calls himself a maâlem, but there's a difference between calling yourself that and actually being it.

I see.

He's from Fez. His father was a maâlem, and in order to become a maâlem, he learned the repertoires of all the different Gnawa groups throughout Morocco. There are, I think, three or four main schools that each have their own repertoire. So the repertoire from Fez is different than Casablanca is different than Marrakesh, different than Essaouira. He knows all those styles. In the past, a maâlem was expected to do a ceremony, a lila, in all those different places. So he traveled with his father, learning all these repertoires. He is like an encyclopedia of songs; they just keep coming.

So I did a few songs with the guys from Innov Gnawa, and then after the pandemic, I wound up connecting with Maâlem, and put this thing together. As you said, there are lots of different fusion things with Gnawa. But I always felt that they sound like fusion, and that was never something I wanted to listen to, like tight arrangements and really arranged charts for the horn section, and tight endings. It's a little on the nose for my taste, you know?

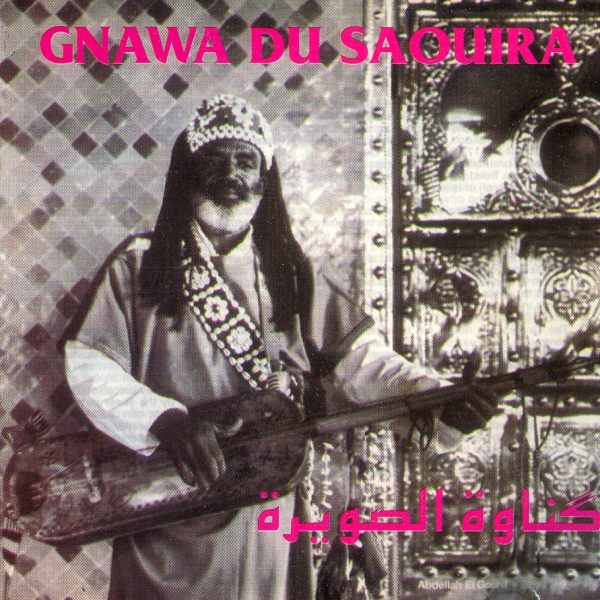

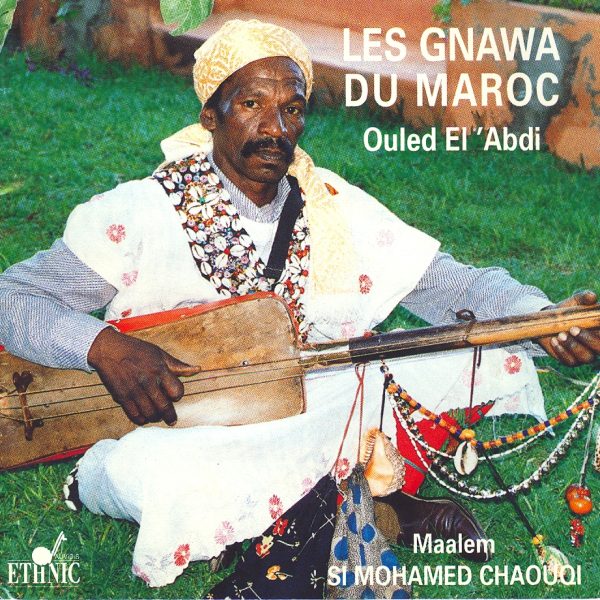

I hear you. I have a shelf of Gnawa Essaouira CDs. They have all sorts of fusion music, but no credits, so you don’t know what you’re listening to, but you get a sense of the spectrum of approaches, and some can feel quite contrived.

I also feel like, because we're in New York, there are musicians who are on such a high level of being able to create different things in the moment, that they can interact with and follow him. And Maâlem is such a folkloric musician; it would be an unnecessary struggle to try to get him to conform to arrangements, even playing the same songs. He really feels the room and just launches into something that feels right. If the energy is low, he chooses something different, or if we need a break, he goes to another thing. So I really just try to trust that, to trust him that he always does the right thing musically. And then also the people that I'll bring will listen and understand the concept that, even though they're virtuoso musicians, it's really not about soloing at all.

Not a place to show off your chops, no.

That’s not interesting to us. Like Jason Lindner. He's so amazing the way he will harmonize something or find spots to fill in. Of course, he could just burn if he wanted to, but he never does. Sometimes we get to a peak and the guitar player will step out a bit.

I hear that. Now and then, the guitar jumps out, but never in a conventional way. The guitar sounds are unusual too. As a guitarist, I can appreciate the tastefulness and restraint.

Yeah, thank you. Gilad Hekselman has a beautiful way of feeling and interpreting this music and he played on the whole record. Donny McCaslin, the saxophone player, is a good friend of ours and he lives near the studio. So he just came by. For this record, the engineer Phil Weinrobe was really smart and put us all in one room with no headphones. He actually put the vocals through an amp. So we set up like we're at a gig.

The voice sounds quite different from track to track. Some of them feel very direct and others sound processed, with lots of reverb.

He was an incredible engineer in that he was able to get so much separation. We're in this small studio beautiful stood called Figure Eight that Shahzad Ismaili built? Do you know him? He’s a drummer and bass player.

I do know him. Our Zimbabwe band Timbila once did a gig with him. Very cool guy.

So he built this studio 10 or 15 years ago in his brownstone in Prospect Heights. There's an upstairs studio and a studio downstairs as well.

I went there once. He's got a lot of cool old gear there, right?

Yeah, yeah. Lots of old synths. He's got a Neve desk and great mics and really smart guys who work there. So once we were set up, we just played. Maâlem didn't even tell us what the songs were; we just played. The other Gnawa guys, the chorus—they call them the koyo —they know the songs and we did do some post-production with them. I recorded the koyos again at my house, just to beef up the background vocals.

How old is Maâlem?

It’s a good question. Maybe mid-sixties? Its amazing to have Amino Belyamani int the band. He is in Innov Gnawa, but also has an amazing trio called Dawn of Midi. He's also a piano player. We did that whole record almost like a gig. We played a set, took a break, played a set, and then I did a lot of the post-production in my studio.

So the guests you have, like Donny and Nels, they were all there for the session?

Donny was there. That's all live. Nels heard it because the guy who was mixing it generally mixes Nels’s records. And he was like, “I want to get on that.” So he came over to my house and played. It was really fun.

Tell me about the song “Tbal,” with Abraham Rodriguez doing that great Cuban vocal.

I have some background in that Afro-Cuban world, and that guy Abraham has been a teacher and friend for many years. He lives near me, so we see each other a lot, and I thought this could work. Actually, I just cut a section of the groove and looped it. Because that part is something that we play in a lila or a ceremony, usually in the beginning to announce that there's going to be a lila. Generally, the drummers will be in the street outside of the house where the lila is happening. They'll play and then it goes inside and it moves to the gembri. There was a section where there was no singing, so I found a little loop, and I had Abraham come over in my house and just put the vocals down. And after that, I sent it to a great Brazilian percussionist, Gilmar Gomes. He recorded some cajon parts. He knows Cuban music very well.

Remarkable.

You know, Brazilians, especially percussionists from Bahia, slide really, really easily into Gnawa music. Now, we’re not using percussion so much, but in the recording session, we had Gustavo Di Dalva from Bahia and Román Díaz, the great conga player. He’s a library, basically; he just knows everything. He was on about half of the session.

So you recorded all the original tracks in one session. You said that Maâlem kind of plays what he feels. So was there a plan as to what these eight songs would be, or did it just flow, and this is what resulted?

Mostly flowed. I mean, we know the standard repertoire that he's done with us. I think there were a couple songs that were a little shaky in the beginning, so I stopped and said, “Hey, I love this one. Let's just start again.” And he'd be okay. Just knowing this was a record date, we try to get it as good as we can, get a start that's compelling… There are a few edits; it's not sacred; it’s okay to edit and work on things. But the general flow is start to finish. This is what it was.

Well, it feels very coherent. I don’t sense any tension between the different elements.

I think that's really a testament to Jason, Gilad and all the guys. Jason has an amazing way of being himself but blending so much. We never want to overshadow the folkloric thing, the spirit. The music is really supposed to make you feel better. It’s supposed to be healing music; Sometimes dance music has a similar feeling of trance. It can grow and ebb and flow. For lack of a better word, it’s a vibe. So we're kind of going for that. If you don't know what to do, don't do anything. Just hang out and it's gonna get good.

The songs often speed up towards the end. That’s a common feature of Gnawa music, isn’t it?

I think it's something you also find in West African music. If you’re in the ceremony, the lila, you're playing and then if somebody gets in a trance, the music will start to get faster, and the person will get more and more into it. And then sometimes it'll peak, and that might be enough for the dancer or the person who's in trance, and then the Maâlem will stop, and then start over.

We don't do this on the record, but often in Gnawa music, there are very slick ways of transitioning to another tempo. That’s actually one of the ways that Gnawa music continues to develop, because you hear people doing those transitions in new ways. And sometimes Maâlem will do something like that, a really shocking turn. We’re here, and now we’re here. (Imitates rhythm slowing down suddenly.) And you’re like, Woah!

It feels great, though, doesn’t it?

Yeah, it feels great.

That's nice. Well, a lot of African music that I particularly love has a sense of an organic trajectory, not necessarily speeding up, though that’s one way to do it, but becoming more and more intense right up to the end. It’s a one-way journey, not a cycle.

Right I mean, a lot of African music speed up, also Cuban music, Bata drumming. Rumba always gets faster.

Sure. That’s true in Zimbabwean mbira music as well.

I remember even playing with Angelique, by the end of the song, sometimes we'd be on a click track, but she would want it to feel like it's faster. So I'd wind up playing way on top of the beat towards the end of the song, especially if we're grooving and she wants to dance. We have to take it up a notch.

But you’re on a click track. That sounds challenging.

Well, speeding up is definitely a thing with Saha Gnawa. And I watch Maâlem really carefully. It's all very intentional.

What about the name Saha Gnawa?

Saha means good and healthy, or cool. It’s just a word that Moroccans typically say meaning “everything is all right.” We were just looking for names, and Maâlem was pretty adamant about it. He wanted it, and I was like, “Great, I like it. Saha Gnawa it is.”

It definitely rolls off the tongue.

I guess. But we don’t have any words with G-N. So we get a lot of different ways of people saying Gnawa. But that's okay. That's what it is.

Back to that idea about Gnawa being very open music. A lot of Malian music is like that, too. And of course, there's a historical connection between Gnawa and Mali. So it's something about the music, but it's also something about the attitude of the musicians, a sort of spirit of openness, a desire to use the music to make connections. Some traditions are much more resistant to that, much more insular. With Gnawa, you have these groovy rhythms and pentatonic scales. All that makes it more accessible to musicians with a background in jazz and rock and blues. But I understand your goal of keeping the tradition in the foreground, and not distorting it too much with those familiar influences.

Thank you. You totally got it. That's what it is. But also, it's becoming its own thing. We sound different now than we sounded on that record, just like a jazz group would. There’s really room for us to find different sounds and evolve. We had a gig recently at a festival, and the vocal mic was crapping out, but all these kids were dancing like crazy. So we wound up sounding like a really crazy electronic dance band. We were like an EDM Moroccan band, nonstop, and the kids were just jumping. So that's part of it too. It's like Maâlem is really just gonna play the room.

That’s cool.

And then Jason and Guilherme Monteiro are playing guitars. Guilherme is a Brazilian guitar player. He's from Forró in the Dark, so he can play that Northeast Brazil style. It's single-line parts, but grooving. It's like he's a drummer, as grooving as anything. And he's also really adept at following the guembri’s bass lines. So that's been developing. I'm excited to record more.

I remember when Hassan Hakmoun had that restaurant in the East Village. That was the only time I ever really played with a Gnawa musician. We had a couple of jams, and it was very interesting trying to follow his lines.

They're tricky, right?

Yeah, definitely. I mean, I've spent a lot of time learning African guitar styles, which are a lot more about melody and rhythm and single-line rhythmic stuff, rather than chordal harmony. It’s always the rhythm and phrasing that are hardest to catch.

So I imagine that everybody in this band has other projects, right? It's not a band where everybody's there 100% of the time. So how do you work around that?

Um, yeah, that's a good point. I mean, as long as Maâlem and Amino are there, we can do it. There are a few different guitar players that can kind of fit in. We're able to do the gig without guitar and just Jason. We've also done the gig without Jason and two guitars. And Maâlem is really kind. But I know that he likes the way this band is going, whether we talk about it or not. And we are playing BRIC Jazz Fest on October 17th, without Jason. And we'll be at Big Ears with the full band. Nels will be there, too, so we'll try to get Nels up.

I've had a few conflicts myself, so like, “Oh, can this band play without me”? That’s really old school, to sub to your own gig, you know?

That could be scary. When did this band officially start? When did it go from jam session to band?

I think I started playing with some of the guys from Innov Gnawa in 2017, but this band isn’t until 2022. We really all have a big debt of gratitude to Bar Lunático in Bed-Stuy, which is owned by Richard Julian.

Sure, I know that bar, and Richard

So that's how this started. We did a gig there and it was like, “Wow, that felt great!” And then we just kept going and experimenting.

This is the first album.

This is the first album. I did another recording with some other guys, and that got shelved. It wasn't right. So this is the first record of Saha Gnawa. And, you know, everyone always says their band is the best, but every time we play, people are super happy. So it’s been smooth as far as getting out there, and we have we still have some ways to go. I sent the record before it was finished to IMN (a top booking agency). And they were like, “This is great. We'll sign you.”

Can’t beat that. It’s not easy finding a booker.

Yeah, not easy. I know them from some other artists that I’ve played with before. I think the more we can continue to play and people can hear us, the more we will play.

Well, I look forward to catching you guys live soon.

Me too. Thanks for this!

Thank you!

Related Audio Programs

Related Articles