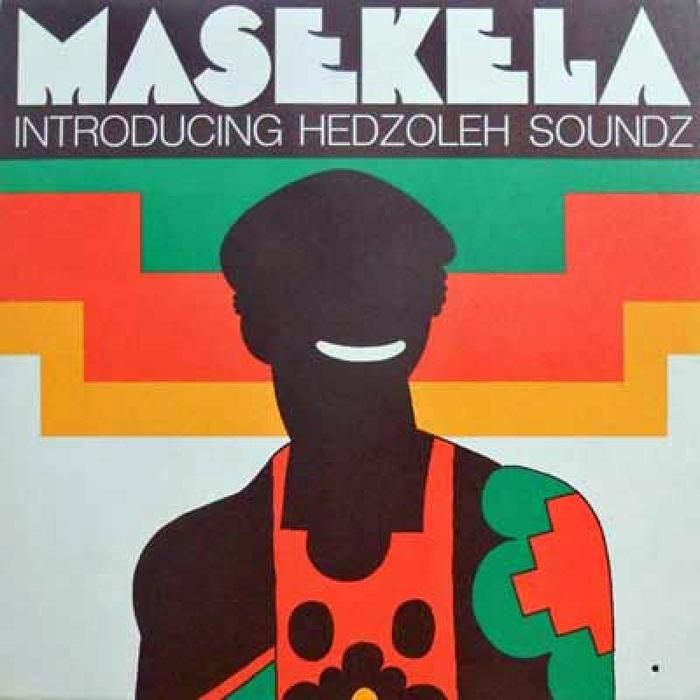

The Afropop Worldwide program “San Francisco: Afropop By the Bay” tells the unlikely story of how a quorum of superb African musicians—from Nigeria, Ghana and South Africa—landed in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s and early ‘80s. These included members of Hedzoleh Soundz from Ghana, brought to California by Hugh Masekela after Fela Kuti introduced Hugh to the band in 1973 and they recorded a classic album together; also Nigerian maestros O.J. Ekemode and Joni Haastrup; and members of the South African touring theatrical show Ipitombi, who settled in the Bay Area and formed the band Zulu Spear.

Together, and with increasing help and support from local Bay Area musicians, these artists created a vibrant live music scene, by all appearances, the first of its kind in the United States. The scene was nurtured substantially in the 1980s, when a failed tour of a Nigerian band stranded some 18 additional musicians in the area. They in turn moved through a series of groups, including some formed and led by Americans. By this time, King Sunny Ade had made two historic U.S. tours, Paul Simon was about to release Graceland, and Afropop Worldwide was about to make its debut. But who knew that one American city was so far ahead of the game? The term local promoters used for this new trend was “worldbeat.” That term would not last, but the music created, and the stories have. Here are excerpts from a set of interviews Afropop producer Banning Eyre did for this program.

Joni Haastrup (from interviews conducted in 2011 and 2013): I started playing music when I was 7, on pennywhistle. That was in 1954. I was also singing. In my hometown it was juju music, but also highlife started coming out in about 1965, '66. Highlife started coming to my grandfather’s palace hall in Ilesha. My grandfather was the king. We were the descendants all the way down from the founder of the town. The king is the descendant of whoever was the first to start that town. In those days the bands that came included Roy Chicago, Victor Olaiya, Ojoge Daniel, C.A. Balogun, and I.K. Dairo. I.K. was the biggest inspiration for everybody, because he was the one who introduced accordion into the music. That was in 1956.

I come from the Yoruba community. But I’ve been hearing Western music since I was a baby, because my family had a gramophone, the record player that you had to wind. In those days, we had all the American and British classics. That was something we heard on the radio. But I didn’t get attracted to anything in particular until about 1958, even 1961 when I started listening to some American music. It was rock ‘n’ roll. Man, I heard everything from Little Richard to Elvis Presley and all those guys.

I decided I was going to be a musician when I started seeing the highlife bands, when I saw the way they dressed. They dressed so nice and clean. Victor Olaiya’s Allstars International were my inspiration as a boy. I had my first job as a musician in 1964. My brother started a rock ‘n’ roll band in Akure. He was working for the minister of agriculture. He was in a school of agriculture. He started learning guitar in 1961, and in 1964 he became a really good guitar player. And so he started a band called the Sneakers.

We went to play a festival in Lagos, and I asked my brother if I could stay in Lagos. It took me a whole night to convince him. So one Sunday afternoon, Victor Olaiya’s band was playing at Cockatoo. And I went to watch them. I met the band manager. His name was Teddy. I met him at the bar and introduced myself to him. And I asked him, "Can you ask the bandleader if I can sing a song with them?" The owner of the band told Victor Olaiya about me, and so they found me and invited me to come audition. So I went there the next Sunday and did the same song I did before, “Midnight Hour,” and he asked me to come sing with his band. He said, “You can sing soul music and we play highlife music. OK?" So I became the soul singer in the band. I had all that James Brown songs down pat.

When I was singing with Victor Olaiya, I had a chance to show the entire nation that I could sing. I was nominated by the media; I was selected as Soul Brother Number One in ‘67. I went from Victor Olaiya’s band to join a soul band called Coasters International.

I didn't make my own group until 1971. First, I worked in Fela’s club, Afro Spot. That was where Koola Lobitos had moved to. I knew Fela a long time ago. Fela came back from England playing the trumpet. He played trumpet and did everything like Miles. He didn't like me because when he came back from England, I was already famous in Lagos singing rock 'n' roll and soul. He went to a school of music, and being a jazz musician, he was way over his head as far as who he thought he was. So anything going on in Nigeria was very, very little to him. Koola Lobitos was the best band Nigeria has ever had. Fela, being a music professional, he got the best musicians, and directed everything they played. They had manuscripts and everything.

The first time I asked Fela if I could sing with his band, he looked at me and said, “Joni Haastrup, I know you are a big star in the soul music world. You can’t sing with my band. You can't sing my songs with my band because you don't understand jazz." And I said to him, "Fela, try me. Because I've got the best ears in the world for music. I can hear every note that everybody plays in every band that I'm with." And so he took a whole week to think about it.

The next weekend, I went back to the club, and I asked him the same question again. And he said OK, "Joni Haastrup, nobody sings my songs with my band. But because you say you want to, I want to hear you. I will call you on stage. Sing one of my songs with my band, and show me what you can do." That's how I got it. And so he called me on stage. I went to do one of his new songs with his band. He sat back and listened and he was sold. He couldn't believe it. He could not believe it. He talked to the audience about me and everything, and from that day, every night I went to his club, he called me on stage. That's how I became Fela’s friend.

I went on the road with Coasters International, on a long national tour. We came back in 1969 now, and I went to Afro Spot. And the band was playing called Hikers. The Hikers saw me come in the club and invited me to sing a couple of songs with them. So I went on stage and did "Hey Jude," and Sly Stone’s “Sing a Simple Song." And on my way down from the stage, after I did my two songs, this white guy came and wrapped his arms around me and told me I was very impressed with the way I sang that Sly Stone song. And he said, "Why don't you come and sit at our table with us?"

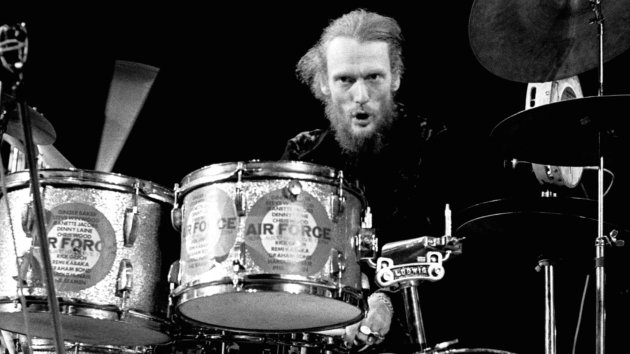

So he invited me to their table where they were drinking. He'd been invited that night to the club by a Nigerian music bigwig, Victor Dogo. So I went to sit down with them, and Victor said, "Joni Haastrup, do you know who that white guy is? That’s Ginger Baker.” I sat with them and had a couple of beers with them. And afterwards, he said, "Well, I'd like you to come and sing with my band in London."

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK: Ginger Baker performs on stage with Ginger Baker's Air Force on April 4, 1970 in Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo by Jorgen Angel/Redferns)

COPENHAGEN, DENMARK: Ginger Baker performs on stage with Ginger Baker's Air Force on April 4, 1970 in Copenhagen, Denmark. (Photo by Jorgen Angel/Redferns)

The shows in England were wild and crazy. Ginger had gotten into African drumming. And because of his involvement with African drumming, he became very egotistical about drumming. He started to blast American jazz drummers. He blasted Art Blakey. He blasted Buddy Rich, Elvin Jones. Anyway, I sang with Ginger’s band in England, and we went on tour in Europe. That brought me to the point where I said, “I'm going to write my own songs.” I promised myself that after I came back from singing with Ginger Baker, no more Top 40. No more copying for me. I have to write my own songs and become the Nigerian James Brown. And that's how I started writing my own songs.

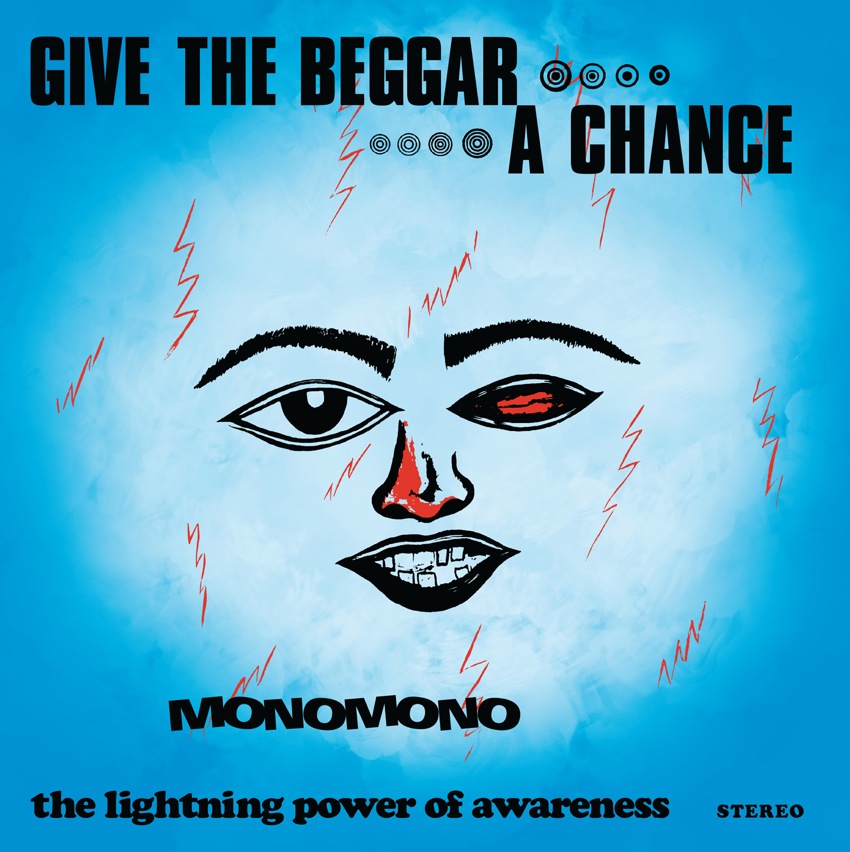

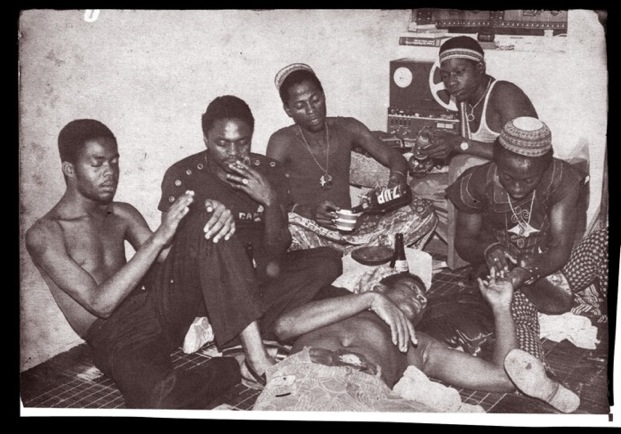

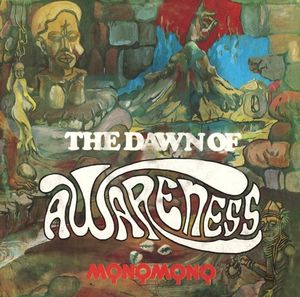

In 1971, I formed my own band called Monomono. I had learned a whole lot from working with Ginger Baker. I learned that he got his bands together by having a jam session at a hall in London. So I started organizing jam sessions to get musicians in Nigeria. And one night, was on my way to Fela’s house. I had been meditating in my house about what I was going to call the band. And I came up with this concept called awareness. And it came to me in my meditation that the power of awareness is a stroke of lightning. I came up with the power of awareness is like lightning. And in Yoruba, we called lightning monomono. So I called my band lightning, in the Yoruba language.

[Before leaving London, Joni had faced mistreatment from Ginger Baker’s management, and it became his inspiration for Monomono’s first big song.]

I started to think about the fact that in Nigeria we have beggars who come from the north, Hausas, to beg for money. And they had a chant that means, "Give me some money. Give me something." And so, when I was thinking of what the management did to me, and how they treated me like a beggar, that song was in my head all night. So I went home and took my pen and paper and I took up my guitar and I sang that song all night. And that was how I composed “Give the Beggar A Chance.” Then when I started Monomono, that was the first song.

Monomono, circa 1972

We did a tour of Ghana with Hugh Masekela. I met Hugh here. We met in L.A., and we did an album, or a single with him. This was after he had met Hedzoleh Soundz.

[Hugh encouraged Joni to think about visiting California and getting into the music scene there. Hugh helped hook Joni up with Capitol Records, which released Monomono’s second album, Dawn of Awareness. Capitol brought Joni on his first trip to Los Angeles. For the record, Monomono studio musicians for Give the Beggar A Chance were Joni Haastrup, Ken Okulolo, Friday Jumbo, Candido Obajimi, and the revered guitarist Berkeley Jones (who later formed BLO, Nigeria's other legendary Afro-rock band of that time). On Dawn of Awareness, Berkeley was replaced on guitar by Jimi Lee Adams (Danjuma Adamu), and Candido was replaced by Ghanaian drummer Stephen Kuntor.]

I spent from ‘75-‘77 in California. I was in Berkeley for awhile. Hugh Masekela brought Hedzoleh Soundz. They guys left L.A. and settled in Santa Cruz, and they heard I was in town. Then I was living in Palo Alto. I heard that Hedzoleh Soundz was in Santa Cruz. They said, “We need you.” So in ’76, I went to Santa Cruz and rehearsed with the band. We did a few gigs in ’76. Then toward the end of ’76, I brought Hedzoleh Soundz to Berkeley, and we played a club called Reunion in San Francisco.

But when we came to Berkeley in ’76, nobody wanted to hear us play, because they had this cliché in their minds that Africans were supposed to be playing traditional drum, and wearing skirts and having a bone in their nose. They heard highlife from Hugh Masekela. But they didn’t know Hugh Masekela as a highlife musician. Hugh Masekela was a jazz musician. People didn’t know he was African.

So I tried to introduce them to highlife music, and then pop. I played with Hedzoleh in the Bay Area in ’76 and ’77. Then I went back to Lagos, but after Monomono ended, I came back here in January 1979, and decided to stay. When I came back, I was still playing with Hedzoleh Soundz. We started playing in the East Bay, at Ashkenaz and other clubs. Actually, I made Ashkenaz happen. Ashkenaz was a dance hall. I turned it into a club. Because my band with O.J. Ekemode in 1980 started playing at a club called Michael’s Den, on 10th and Gilman. Ashkenaz was trying to decide where to go, and David Nadel called me and said, “If we make it into a club, will you play here?” I said, “Yes I will.” So he then started Ashkenaz nightclub.

Worldbeat was started in Berkeley with my band, Hedzoleh Soundz, O.J. Ekemode, Zulu Spear, later on Mapenzi and some other bands. That was how worldbeat started. I loved it, because it was a continuation of my experience. I didn’t have to change my direction. Back in Nigeria, I started my own genre, Afro-funk. And over here, there was Bootsy Collins. He and George Clinton started the whole thing about funk. And I said, “What am I going to call my new formulation?” I didn’t want to call my music Afro-rock or Afrobeat or highlife. And there were so many African bands in those days following me. Afro-funk was the new thing.

A friend of mine who was a DJ started a publishing company called Tummy Touch. Tim called me and said he wanted my permission. I said, “Tim, I will sign with you if you promise me that you will use your company to find all my royalties.” Because EMI owned my records. Also Capitol had released us in Caracas.

I couldn’t make more records because I didn’t have money, and it’s damn expensive. Releasing those three Monomono CDs, that was Tim’s idea, in 2010. Give the Beggar A Chance was number one on iTunes World Music charts for three months. I got a little money. I’m now living on money from records I made in the early ‘70s, first time in almost 37 years.

Annual solstice jam in Oakland, CA: Still going on today (Eyre 2015)

Annual solstice jam in Oakland, CA: Still going on today (Eyre 2015)

Jackie Gay Wilson (Baba Ken Okulolo’s wife and co-manager): It’s all Joni Haastrup’s fault. It is. Really. He introduced us. I am originally from Michigan, and I fled that limited and very segregated society in 1966 and came to the paradise of California. I was part of the peace movement, part of the racial justice movement. Because of the conditions of society then, largely from the age of 15 up, I was integrated into the African-American community as a family member. But then, in 1973 or ‘74, I found myself childless and mateless. And I went to see the African Ballet at what was then Zellerbach Auditorium. I was struck by the joy that was expressed in these people looked like the people that I normally associated with, and yet had a certain confidence and freedom and a form of expression that I thought, Well, gee, I'm looking for something different in my life.

I saved up my little pennies and decided I would just go skate around in West Africa, which I did for six months, on a shoestring. Nineteen seventy-four was when I actually got over there. I started out in France, quickly got to Spain. And then to Morocco, then I got a freighter around the horn down to Dakar. I was constantly supported and taken in by people. I was never allowed to be defenseless or alone or anything. People always welcomed me. The time when I was there, people had a lot of hope that this was the era of empowerment. This was when money was going to begin to flow. Society had not fragmented, and it was really just very safe and comforting and wonderful to be there.

I was always seeking music, always trying to find out stuff in French-speaking West Africa. This is where I got turned onto salsa music, because they were doing the pachanga and all that stuff. But getting into Ghana and Nigeria, there were always front-page newspaper articles about Fela and the trouble he was causing, the popularity of his music, his ganja. And then the other groups that were being written about were Monomono and BLO.

Monomono were being lauded as people who were incorporating African sounds with modern rock sounds. And the first time I went to the little kiosk by the side of the road and asked them to play me the Give the Beggar A Chance record, then I sort of fell over the cliff with joy. That was my first time of really hearing what I later learned was the 12/8 rhythm. And that feeling in my body for the first time was just a wonderful revelation. And I ended up going to one of their concerts. I went to Fela concerts, I went to Sunny Ade concerts. I went to as much as I could.

One day a friend introduced me to Joni Haastrup, and he said, "Oh, I'm coming to your area. Give me your business card." So I did. When he landed over here, he called me. He’d been helped by a businessman from Nigeria, Sola Sobayo. They had rented a house on University Ave. in Palo Alto, a house that must be worth millions by now. It had no furniture in it, and they had pretty much just dropped Joni off there. Then he got turned on to the Berkeley community, and he began putting together his band, which was of local people, whoever could be picked up.

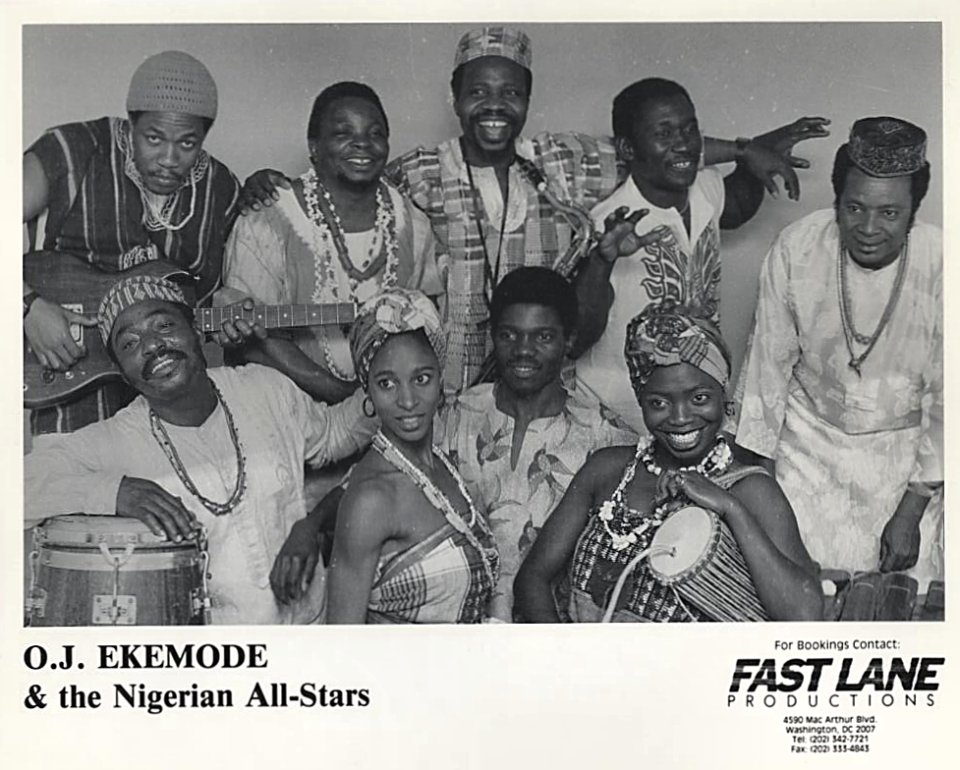

O.J. Ekemode had a very popular band, again, almost all Americans--the Nigerian All-Stars came a little later. And they were playing multiple nights at Ashkenaz, and there would be lines around the block. And Joni’s band, and then there had been this tour by Hugh Masekela, when he brought Hedzoleh Soundz to our area. There's a fellow here, C.K. Ladzekpo, who is from the Ewe tribe in Ghana. He had begun teaching African music and dance at U.C. Berkeley and at various places. So when the Hedzoleh guys arrived here, he knew them. They were old homies. And C.K. encouraged them to drop off here.

But when these bands arrived, there was instant fragmentation. You may have observed this phenomenon, that once band members from Africa come to America, each member becomes a bandleader, and there's that sort of magnetic dis-attraction. People want to put on wings and fly and see how far they can go. And it's very empowering, and a lot of great things that come out of it. Some people did end up in Santa Cruz. In fact one of the Nigerian All-Stars, Danjuma Adamu, remains in Santa Cruz, and he puts different bands together. The band he first joined up with in the U.S. was Ntu Shamala. His own band, which he founded in Santa Cruz, was Kosono.

So there was this big buzz going on. And you probably know, in music it is largely about the buzz. What people go to, what they gravitate to is largely often dictated by the bandwagon effect. So here was the worldbeat movement, originating in Berkeley, having been started by Salsa de Berkeley several years before that. But now Hedzoleh Soundz was in town, Zulu Spear was in town, O.J. was in town, Joni was in town, and Big City was going on, and Mapenzi. And they were blasting it out at Ashkenaz, extremely popular there. And there were festivals. People believed that this was going to be the next thing after reggae.

[A note on the band Mapenzi, formed by marimba player and guitarist Brett Stewart. Brett had been a student of Dumisani Maraire, the Zimbabwean educator who generated much interest in Shona music after arriving as a visiting artist at the University of Oregon in 1968. Mapenzi formed in San Francisco in 1983 and had a spectacular run with a full-on fusion approach to marimba music, including super-fast grooves, a brass section, and an engaging stage show. They often performed as a collective under the worldbeat banner with the bands Zulu Spear, the Looters, Big City, and the Freaky Executives. Unfortunately, Brett Stewart died in 2013. But ex-Mapenzi musicians continue to perform and record, from the Bay Area to New York City.]

The trouble is worldbeat, or world music, is a mishmash. Reggae is one thing. If you want to hear Latin jazz, it's montuno or cha-cha. If it's reggae, it’s reggae. But if it's African music, it's any number of things. If it's worldbeat, it's an even greater number of things, and you know, pretty soon Irish was world music, so it was all a bunch of orphaned music. And unfortunately, maybe due to some of the band members had personal problems with substances or whatever, or with bad luck. The money never materialized. I think they got a lot of support from music journalists and people really have a lot of goodwill around it, but it just couldn't support itself.

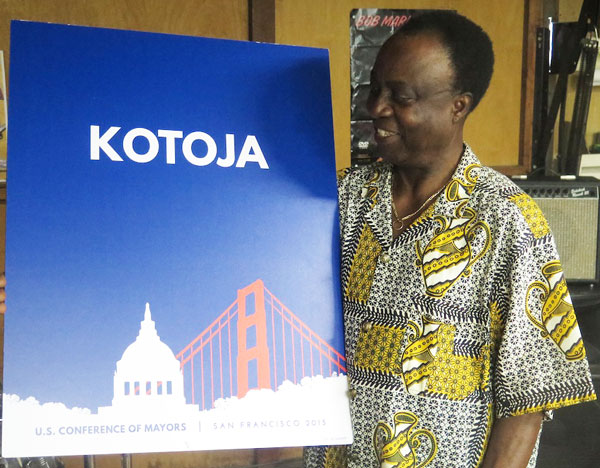

Baba Ken Okulolo (Veteran of Victor Olaiya, Monomono, O.J. Ekemode, and leader of Bay Area bands Kotoja, West African Highlife Band, the Nigerian Brothers and other projects): I was born in 1950 in Aladja, a village in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. It's across from the oil city of Warri. And Warri is a seaport, and a very vibrant city when I was growing up. I never actually crossed over to Warri until my dad passed away. As a traditional African cultural thing, when the head of the house passes away, the children are distributed to extended families, because my mother couldn't take care of seven children by herself. So I was taken to my auntie in Warri.

I actually fell in love with music at that time, because musicians were very well dressed, very well respected, and I loved the way they dressed. They would pick up their instruments and go to the club in the evening, walking very majestically, and lovingly. I was probably a bit naïve at the time. I didn't know about the criticisms of musicians. I was fresh in the scene, and what I saw, my perception, was that they were well treated. They were paid. They were cared for. They looked clean. They performed well, and that was just what attracted me to become one of them. I said, "This is a unique and a nice profession, where people just enjoy what you give to them. You give them a life of enjoyment, and spiritually they are uplifted with what you give them." So naturally, my soul tells me it's nice to make people feel happy.

Baba Ken Okulolo at home in Oakland, CA (Eyre 2015)

Baba Ken Okulolo at home in Oakland, CA (Eyre 2015)

I have educated myself as a musician. I never had formal musical education. I learned with my ears; most of us in those days learned by ear. The record comes in, we put it on the record player, everybody picks their part. You listen, and you pick your part.

Highlife music was the classic music of West Africa at that time. Aside from that, you also had to learn how to play ballroom music, and music from the West—if you wanted to be employed. And music then was being run by proprietors. At that time, you don’t have your own instruments. The proprietors have the instruments. They hire your services. They give you the instruments, and some of them are kind enough to give you accommodation. But once the contract is over, or you decide to move on, you leave the instrument behind.

I started playing professionally as a musician at the age of 18, after getting some really good lessons from my brother, the guitarist. He taught me a few things on the four strings of his guitar, because I never had a bass.

[Baba Ken moved to Lagos, where he was recruited into Victor Olaiya’s band on bass.]

Joni Haastrup was the soul singer of the band, and we worked together for I think about three years. Then he left to join Ginger Baker's band, and I stayed behind. When he came back after finishing Ginger Baker's tour, he had lots of ideas about getting a soul band together. So he contacted me and said, "Let's start something new." And that's how Monomono was born. We practiced and got enough songs together and went to EMI Records and recorded Give the Beggar A Chance.

And then the record did so well. It was a great album. Till today, if you hear the sound, it's just like he was ahead of his time. And really, we put some work into it, and then we did a second album, The Dawn of Awareness, also for EMI. It was not as successful as Give the Beggar A Chance, but it was a great recording as well.

In 1984, I had an invitation with Sunny Ade to do a tour, a world tour. He was looking for a versatile bass player. And the tour was sponsored by Island Records. This was when Bob Marley had passed away, and Chris Blackwell was looking for new talent. So Sunny Ade was signed on, and he did a recording for Island Records. So I went on that tour with Sunny Ade, throughout Europe and America and Japan. That was a very successful tour, and during that tour, at the Greek Theater here in Berkeley, O.J. Ekemode was there.

O.J. had been my bandleader back in Nigeria. He did the same trip as Joni. He said he was coming to the U.S. to get a band over, which he never did. But he met and teamed up with Hugh Masekela as well, here. And they did an album called The Boy’s Doin’ It. So we were playing at the Greek Theater, and he came to the show and sought me out, since we were buddies in the past. He said, "I’m coming to Nigeria to record an album. And after the recording, I want to bring the band over here to promote the album. Can you get me a band together, coming at such and such a date?" So when I ended Sunny Ade’s trip, I went back home and put this big band together.

Well, O.J. came as promised. The album was done. The video was done. The band was rehearsed for almost a year, then took off, finally, from Nigeria to here. I still remember the date. It was Oct. 1, 1985. We landed at JFK and took an old bus that was used in a movie called Bus Stop. A really old bus. And we traveled across the country to Vancouver, in Canada. We did our first show there, and came back here.

Jackie Gay Wilson: When they got to the airport, they were put into this bus that had been used in the Marilyn Monroe movie Bus Stop, which had been made in the ‘50s, except, whoops, it was 30-something years later. So this raggedy bus. They had no hotels, no stops for showers. They drove them straight to Vancouver. They did the gig there, then they came down here and did a gig at Wolfgang's, a really cool venue.

And that was the night that Joni said to me, "Hey, let's go see our buddies who have just arrived here." And he introduced me to Baba, as we call him now. In those days they called him Kenet! And Kenet [Kenneth] was again a personal approach, not as a possible love interest but as a friend who radiates, as you can see, a very spiritual quality and a very wonderful humanness. He was crashing around the corner with a friend of mine. They begged me to take in three of the Nigerian All-Stars, and it was actually in my living room where they had the whole band come together, and C.K. and O.J. announced to the band that their contract was—as has become a famous phrase—“down the drain.” They would have to scrounge. They were crashing. They were just crashing all over the place.

There was a lot of shuffling, a lot of rivalry. And one of the things that struck me about all the injustices and all the outrages that that I witnessed was a huge life lesson for me. When it came time to be New Year's, they would all call each other and greet each other and bless the new year, and pretty much wipe the slate clean. Whereas in our society come we are raise that da bad guy's a bad guy and a good guy's a good guy, and you've got to make justice happen. This really changed my life.

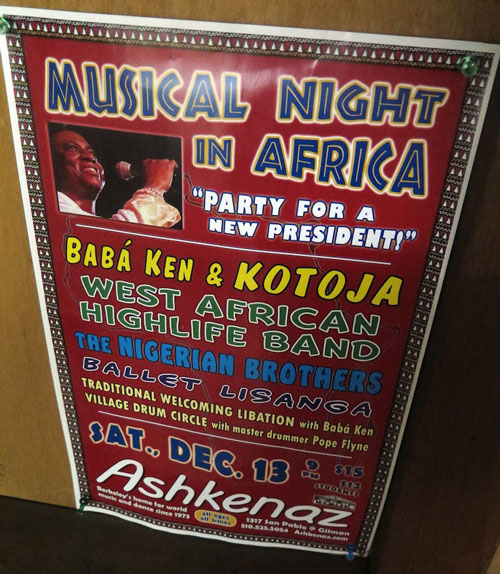

Baba Ken Okulolo: So everything was up in the air when we arrived. Things were not properly put together. Part of the tour was already canceled. We just did a few dates, and everything stopped here. We were just stranded here. I mean were talking about 18 people. It was a big band. So when the group just got stranded here, I said, "Well, I have some songs I've written. Why don't I just get some of the guys and start a group of my own?" And that's how Kotoja was formed. Kotoja just means "This is worthless. It's not worth fighting over. Let's start a new beginning. And let's just be friends." So that's what it stands for. Forget it. It's not worth fighting over. I got some American musicians to join as well. And then we did an album Freedom Is What Everybody Needs, and then we followed that up with Sawale. Mesa Blue Moon sponsored that recording.

When I arrived here, there were several African bands. There was Zulu Spear, there was Mapenzi, there was Big City, there was Salsa de Berkeley. There were several of them, in the popular eye because they were playing Ashkenaz. And sometimes they would book each band playing there three nights a week, and the place was packed. African music was just hot then. The first gig Kotoja did was in 1986, at Ashkenaz opening for Zulu Spear. And David Nadel, a very good friend—may his soul rest in peace—liked the band and continue to book us in the club until he passed away. And I continue to play there until the present—almost 30 years now. That was my home base. If anyone was looking for Kotoja, they know where to find Kotoja.

Andrew Carriere and his band perform at Ashkenaz in Berkeley, CA.

Andrew Carriere and his band perform at Ashkenaz in Berkeley, CA.

Jackie Gay Wilson: The first time they came out at Ashkenaz on a Thursday night, the poster that we wrote up, and he and I posted all over town, said: "These are members of Hedzoleh Soundz, King Sunny Ade’s band, Fela’s band…” All these bands that people knew, and this venue that had 175 capacity sold 600 tickets that night. So that was how eager and into it people were.

Baba Ken Okulolo: Kotoja started out playing not Afrobeat. We are playing contemporary Afro-funk, Afro-fusion. That's a carryover from the Monomono style of music. I call it an extension of Monomono’s music. Very lately, I've been writing Afrobeat stuff. But Kotoja was contemporary Afro-funk, Afrobeat, Afro-fusion band, with a big sound.

The song “Sawale” itself is a remake of Rex Lawson's highlight hit in the '60s. The song talks about a young girl who found herself in the big city and was liking the life of the big city and was, you know, kind of selling herself to survive. Fortunately for her, her brother saw her on the street doing this and said, "Well, this is not a good profession, my sister. If you don't leave, I'm just gotta run back home and tell our parents what you're doing. Please stop and go back home." That's the story of that song.

At the time, I had about three female singers, and a horn section of about four, two guitars, keys, drums, percussion–it was a big band. I mean, every African band that plays either Afro-funk or Afrobeat or highlife can't be less than six. It has to be more. Because we as musicians and Africans, we like the family thing, we like big. Big sound. Big sound is good for the ear and the body for the listeners, but there's not much money in that. As I found out very late. So right now, I just have two other smaller bands that I work with a lot. One is the West African Highlife Band, and the Nigerian Brothers, which does folk music for people who've been to Africa, they want safari parties and stuff like that. This band is for them.

Mesa Blue Moon, being a little label, didn't have enough money to push it. They didn't put the band on the road to push it, so it just fizzled away. I remember at one time, we were number one on college radio stations for several weeks. That was the time they would've done the promotional job, but they failed to do it. And after a year or so, they gave up, and that's when Dan Storper stepped in and bought the two albums, Freedom and Sawale, and made his own compilation. He called it Super Sawale.

Dan Storper (founder of Putumayo Records): You know, I think life is often a series of somewhat serendipitous circumstances, occasions, happenings, and I was walking through Golden Gate Park, and without really any consciousness or thought about it I started hearing some sounds. I just kind of, obliquely, heard music playing and it sounded interesting, so I said “Let me just walk over and check it out.” And there was a group of maybe 70 or 80 people and an African band performing and it was literally their last, say, two songs. It was a group called Kotoja. And I basically stopped in my tracks. There was something about the music that was so captivating and so uplifting. The crowd was rapturous, even though it was a small crowd. There was an Asian woman dancing with an African-American guy and I was struck by that magic moment where, somehow, all the cares, all the worries seemed to disappear. There was just great music and people having a good time in a beautiful setting in Golden Gate Park.

Baba Ken Okulolo: Dan did a good job. Because he put the band on the road, actually took us to Atlanta during the Olympics. And we did shows at the Olympic Village. He took us to New York. We did several shows in New York. And also in Washington D.C. He did the best job he could do at that time for that kind of music.

The Bay Area had it all then. It was a mecca for world music—a combination of music of the African diaspora and music of the world. Those days, I mean, to book one band for three days back to back and pack the place. I mean there were lines around the building. The technology was not that much of a factor then. People didn't have all these things they have now in their homes to enjoy themselves. They were going to go out and have fun, which is something I miss these days here. Everybody is cocooning in their houses and enjoying all their technology they have today. Today, we can hardly get a full house now at Ashkenez.

[In the Bay Area’s African music heyday, Baba Ken was surprised at first to find that the audiences were mostly white. Local Africans came out to support bands they felt ethnically related to—Igbos for Stephen Osita Osadebe, Yorubas for Sunny Ade, South Africans for Hugh Masekela. But whites, especially young ones, wanted it all.]

They wanted to experience something new. Since if they couldn’t go to Africa, and African music came to them, they wanted to see it. They wanted to hear it. They want to feel it. Even though they're not really good dancers to it, they can enjoy it. They can move to it, which is something I like about them. Because they are free. Their body is free. They let themselves go and dance the way they feel. That's how you're supposed to enjoy music, by the way. You set yourself free and just let the music take over.

Solstice jam in Oakland, in year 35 (Eyre 2015)

Solstice jam in Oakland, in year 35 (Eyre 2015)

For the African-Americans, why they didn’t come, that's a question I keep asking myself. Maybe they have a biased mind about Africans—the way their forefathers were treated back then during the slave trade. They look upon us as they don't want having to do with us, because we betrayed them and they're still mad at Africans. Maybe. I don’t know. Every now and then you see one or two of them drop in. They're curious to hear what is coming from the Motherland.

Also, they can't really dig deep into the music traditionally, because they don't have the root from where they came. They’re kind of guessing. Where is my root? How do I get a hold of my root? Even though the music is still there, embedded in their soul. That's why their music is very upbeat, even if the lyrics don't make any sense to me. But the beat itself is very catchy. The beat is universal. Everybody in the world emulates black music, most especially African-American music. They've got it. They've got the beat, they've got the soul. They've got everything. And it's a commodity that they are proud to sell all over the world, even to Africans.

You know, young Africans these days, they don't play the kind of music I was playing when I was growing up. They play American music. They imitate African-American music. So they've got something. It got a commodity that they have sold to the world, and they are satisfied with that. So why look for something else?

Well, at the end of the day, the Bay Area is home for me. It's been home for me for almost 30 years. I love it here. I don't think there's any other place in America that I would rather stay than the Bay Area. It's a community that thrives with people from all over the world, and there's no better weather, no better place to be than the Bay Area. I have my family here, and life is good.