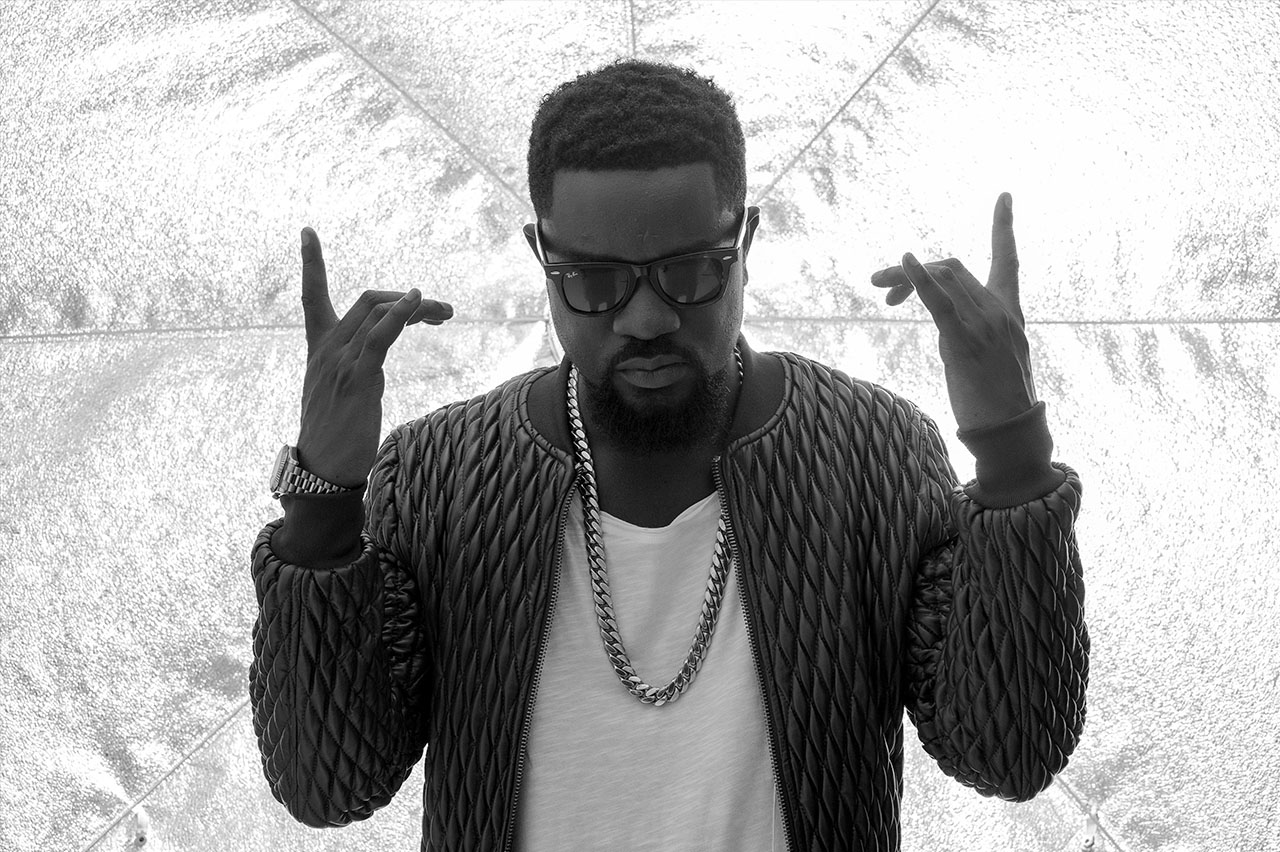

Ghana’s Sarkodie [Sar-KOH-dee-yay] is one of the most acclaimed and successful rappers in Africa today. In an independent, self-driven career, he has built a formidable global following. 2021 sees the release of his sixth album, No Pressure, a blend of hard rap, Afrobeats and even gospel. Afropop’s Banning Eyre reached Sarkodie by Zoom to speak about his career and the new album. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Sarkodie, I am reaching you in Accra, right?

Sarkodie: Yes, you are.

We were there in 2013 and tried mightily to interview you, but without success. So I'm very glad to reach you now.

I appreciate it. Pleasure.

Why don’t you start by introducing yourself to our audience, who may not know that much about you. We’ve been going since 1988, so we’re a bit tied to the old school, if you know what I mean.

Sure. Well, I was born in Tema, in Greater Accra. I lived there with my mom and dad for awhile. We moved to Koforidua in the east, then came back to Accra. I spent a lot of my childhood at Achimota, Mile 7. I went to school there. That was definitely a time that was a bit dark in my life as a child. So it built this whole persona of Sarkodie as a laid-back observer. I like to watch life happen and go with the flow. I like to watch things from my quiet corner; I was always observing. So that started with me just writing, not necessarily music. It was just me writing stuff that I thought about on a regular basis, random stuff. I used to watch everything that was happening and just try to pin it down.

Then I fell in love with rap music, of course, because I was young and had that youthful energy. Then I realized, “So, O.K., in that music you can actually say all these things, and take it as a profession.” So I fell in love with it. It just started with regular writing. Then I got into music by just falling in love with the art.

At what point did you start to think of it as a career?

I think it was when the demand started coming, when people really wanted to hear from me. That's when I realized that people could actually pay to see you. It started out just doing battles, doing radio shows where people call in. I used to go on radio, a station called Adom FM in Ghana, back in the days. Every Saturday, they would have a battle, a freestyle session, and anytime I didn't go on the radio, I would get people calling, “Where is Sarkodie? Where is Sarkodie?”

So I would go to places to perform, like small pubs and bars. Then people would go there thinking I would come again. So I just saw the demand. That's when I realized this could be something like a full-time gig, and then I took it seriously.

You sure did. I believe this is your sixth album in 10 years. Have I got that right?

We actually forgot one album because of how it was presented. So technically, this is my seventh album.

You were born Michael Osusu Addo, and Sarkodie is your artist name. I've read that it means “eagle.” Why did you pick this stage name?

It's actually a surname. So it's quite funny. Anyone who bears the real name thinks I'm part of the family, but it's just coincidental. There are two reasons why I picked that name. My dad had friends and I saw a couple of Sarkodies, and I don't know if it was coincidence, but they were all wealthy. They all had money. So as a child, I thought it may be the name that had an impact on them. Then it became my brand. I don't know why, but I always related to the eagle. The name in Twi is okodie so Sarkodie is “like the eagle.” So I just love the name, and the fact that it had that coincidental wealth related to it, and then it also sounded like the eagle. Those are the reasons I chose the name.

I relate to eagles too. I was actually interviewing an artist in Kinshasa yesterday who had a pet eagle that he showed me on his phone.

Wow. I would want to have one.

I imagine that would be a handful. So the way we first heard of you in Ghana was that you were the fastest rapper around. You were the guy who could just pack more words into a minute then anybody. How did that happen?

Well, I am a fast talker. Recently I'm trying to slow it down. I naturally talk fast. I have certain moments when I stammer when I speak, so I literally have to talk fast to be able to get over it. So that's where I possess that power. Then I put it into music, so it's not too much of a hardship for me to rap fast. I can say a lot of words in one sentence. And I fell in love with fast rap when I listened to Twista and Busta Rhymes. I definitely got inspiration from them. I used to listen to them on a daily basis. So I just picked up a lot from them and used my native tongue to do the same thing.

I've read a couple of interviews you did about this new album, No Pressure. I understand that a big part of it is a feeling of freedom that you don't have to answer to anybody. I think you said, "As much as they told me it's not going to work, I made it work."

Exactly.

So what did that pressure look like? What were the kind of things that people wanted you to do differently?

It was a whole lot. The biggest thing for me was the language barrier. I wouldn't rule out that it made sense that I should speak in languages that a lot of people could understand, but at the same time, then I'm literally doing what everyone else is doing to survive. I am an indigenous artist. We have a lot of people who cater to a certain group. Your language is very essential when it comes to music, especially when you're dealing with emotions. You want to be able to express yourself well, to be able to get to the right people who deserve to hear it. So I'm dealing with my Ghanaian people. That's how I thought. Then I said, "O.K., why not? Let me just use the flow and delivery of my language to capture someone who doesn't understand what I'm saying, but appreciates sound."

I use the narrative of the fact that if Eminem is rapping, people who can understand what he's saying take it literally. They know word for word, and they can relate. People here in Ghana don't really relate to what he's saying; they just know how he is delivering the flow. So regardless, everybody has limitations. There's nobody who's got it all figured out. You are definitely going to be limited regardless. So I just stood my ground and said, "These people said I was going to be a local champion. I was going to be appealing only to the Ashanti and Twi-speaking people.” But even here in Ghana, I broke barriers. People here in Accra who are Ga, or people from the Volta Region to the north, they all had the same love. And from there I moved on to Africa and other parts of the world. So it's really me saying to myself that I'm not going to sell my identity just trying to go international. And I was able to prove the point. I didn't have a plan to get out, I just had this feeling in me.

That's why I always tell young ones coming up, there are things you have that no one else can understand. You can't explain it to anybody. You might as well just get along and do it, and that's exactly what I did.

Sure. You have to satisfy yourself first and foremost.

Exactly.

So a lot of it was about language. People told you that if you only rapped in Twi, then people who didn't speak it would be left out. But you didn't see it that way. I know that rapping in every language is different. It works better in some languages than others. What are the challenges of rapping in Twi?

I appreciate sound and I know sound. I really know how to pick beats. I know how to create songs that people are going to love. I've had that gift for a very long time. So I know music. I know sonics. I know what the ear can appreciate. So when I speak Twi, there are certain words that, as much as it makes sense, it doesn't sound right sonically. So I just know how to make the words so that they will please people sonically. When I started out, I didn't used to do that. The typical Ashantis used to love it, because they knew exactly what I was saying., But then when I read the faces of other people, I could see them thinking, "What is he talking about? I don't understand what he's saying." Because there was no flow. I was just saying stuff. But then I realized that there are certain words that just have a sound to them. It's hard work, but if that's your job, you just have to zone in on it. That's what I was doing 24/7, trying to figure out how to find the best words that can sonically please the near. So I got it figured out long ago. I know what types of words to use so that it can be understood by my people, and that people who are not Ghanaians can appreciate the sound.

That is fascinating. Can you give me an example?

It's going to be hard to do that randomly. To date, I still have lyrics that I created for my typical Ghanaians where I don't care too much about the sound. It's more about what I'm saying. With such records, when I played to anybody who was not Ghanaian… Obviously, I'm not going to do a bad record, but you wouldn't appreciate it as much as what I normally do. I just know the zone to get into when I'm about to do something that might go international. It's going to be hard to show you this exactly, but when I'm writing, I know.

What is your process for writing a song?

In all my songs, my first lyrics, the first two lines will show me how dope or nice this song is going to be. So the first thing I say will lead the whole song. When I started, I didn't have access to the studio, and I didn't have access to producers. So then you just start to write at random, take beats and just write, or write without beats. Just write lyrics down, and when you have beats, you try to fix it, to make it work with the progression and the tempo.

But now, I have people sending me beats 24/7, which helps because it starts the mood for me. The beats and the production will set the mood. The tone can tell me that this is a happy song, or this is sad. So then I get into that zone and literally just flow in that. You know, I have songs that talk about sorrow, and people think I'm living that life. I'm not. I just psych myself that I'm in that place, and it's going to come out.

How I get my cadence on the beat is I make sounds with no lyrics, just to get the timing. I'm really keen on timing, how not to land on a kick or a snare. Technically, any beat I get, I try to find something that stands out as the beauty of the beat, so that you don't have to go over it, so that the beat can also breathe as well.

I have a song called "Happy Day." That's a good example. There is a tone that dominates the music, and as soon as I heard that, I know the lyrics that are supposed to go on that song. And that's how the music is going to be beautiful. You have to marry the beats. You have to be in between it. You have to blow on it. So basically I make sounds. The beats can dictate the mood, then I just throw myself into whatever character I have to do.

So you say people send you a lot of beats. I guess they're all hoping you will make a song out of their beat.

Yeah. A whole lot. My email is crazy. I need to cut down. So what I do now, I don't do that anymore. I just have two or three producers that I really trust. I call them normally on Friday nights. They come outside my house. We have the speaker and we just played beats, beats, beats. And I just take whatever I can take if I can record on the spot, which nowadays I don't do very much. Way back I used to record on the spot. As soon as I heard the beat, I started writing. But now after doing it for 10 years, if you're not careful, you might catch yourself repeating something that you've done. So you need to take your time and just sit with it. Now, normally, it can actually take two weeks to do one record. It's a slow pace, but I do the best work that way.

Let’s talk more about this album, No Pressure. I've read in interviews where you describe it as a victory lap, a project where you were free from expectations. You talked about it having “bossy beats,” which is a great phrase. And I hear that. Plus you’re working during the pandemic. Talk about what making this album was like.

As you said, this was a time when I was feeling this no-pressure feeling. I've been feeling it for four or five years now, and just the fact that in the hip-hop thing, rappers’ careers are normally short. If you’re five years in, it's like you're 80 years old. So to beat that, this gave me an idea that… Listen, I've got this figured out. I've been able to go with my instincts, my plan, my vision, my drive, whatever I saw, I just kept real by not being distracted for all these years. So I was able to beat the time.

So when I crossed that line, I think I earned the right to say, "Listen guys, I get it. You have your opinions about what you think I'm supposed to do. But at this point, I think I've kind of got it figured out.” It's not like I can't take criticism. I can take constructive criticism, people telling me something that they think I can add. I always listen. I like to listen. But just the whole pressure of people trying to… A lot of artists have lost their touch because of pressure. Creativity thrives on freedom. You want to be able to be free to be able to create, so just saying “no pressure” is like therapy for myself. I just use that to get all the noise out, just block everything out and concentrate on creating. That's what I did on this project, just go back to the essence of what writing is all about. I'm not thinking about radio. I’m not thinking about nothing, just making music.

A few years ago I interviewed a Congolese rapper, Baloji. He comes out of Congolese music, which as you know has a lot of rules. The audience has certain expectations. But he was having a very hard time being accepted as a hip-hop artist in Europe, because what he was doing was different. And he said that he thought hip-hop was the most conservative music he had ever dealt with. It was a surprising statement to me. But it reminds me of what you're saying. A lot of people seem to think they know what you need to do, and I could see how it would be nice to be free of that.

Yeah. That's the best thing you can do. If not, the art will fall off. That's why for rappers it's hard to keep up. You have to quiet out everything and just see yourself like any artist, whether it be classical music, r&b, country. They're all musicians. It's how you take it.

There was a time that I did not even watch TV. I was not listening to the radio. There's a whole lot I was doing just keep my mind on just the music. Once in awhile I would go out to the pub to see what is happening, check the sounds out, then come back to the studio and zone in—just literally keeping that tunnel vision and not allowing any distractions.

It's interesting what you say about five years being 80 years in rap music. When we were in Ghana in 2013, we did a whole show about Ebo Taylor, who literally is about 80, and he's still cranking it out. Nice if you can last that long, right?

Exactly. I hope.

One thing I noticed about your album is that it has a progression to it. It starts out with pretty hard rap and hip-hop, but then becomes increasingly melodic as it goes along. More r&b. More Afrobeats. And then ending with the gospel track.

Yes. Because my previous album Black Love was dominated by Afrobeats. That's how I am. As soon as I do too much of one sound, I get tired. I want to try something else. But my core fans, the ones who really listen to Sarkodie, it's the no-pressure type of set. They love those type of records, the hard rap. So I just had to get into that. So I thought about when they download the album, I want that feeling of, “Oh, we have Sark back. This is the Sark that we want!” So I just made sure they had enough of me in the beginning, then obviously it can give other music lovers something else.

The masses that really love my music, and not necessarily the fans, they love the music, so they don't care too much about the story. They wouldn’t listen to the real hip-hop records. They would want the Afrobeats. I'm kind of a little bit greedy when it comes to getting all sides of people who listen to music. So I give everybody something that they can relate to. And that's exactly what I did. I then went to the step of ending the whole project with the gospel joint that I know the Christians are going to love, and my people are going to love.

It's a sweet ending. Let's talk about some of the individual songs. Start with “Anything.”

Yes. "Anything" is definitely one of my best records. Personally that's the song that I love most, simply because of the production. There are two things: the production and the message. The production kind of depicts my state of mind now, how comfortable I am, the mood that I'm in at this point. The beat is just perfect to express that. And then the lyrics. Everyone is really talking these days with social media; people doing literally anything just for crowds and trends, just to be seen. A lot of people are lying. The youths are living a lie. People want to act rich but not be rich. So I’m kind of prompting these kids and telling them, “Listen, reality is happening. Fake is the new real. So you have to be careful what you're falling for. You’re better to put in the work and not waste your time trying to follow trends and be talked about on social media. We’re in real life, and you are going through it.”

Most times I find myself talking about things like that, because I think about it. I'm just basically advising the youth on how to live and be very careful about what they believe in.

Amen. A good message, and universal. What about “Whipped”?

Yes, “Whipped.” Interesting title. That came to me from Darko Vibes. He came to the crib and then he said it. He was making a sound, but then he replaced it with “whipped.” I loved it when he sang it. He's basically talking about being taken over by a girl's love, and not being able to be yourself when she's not around. You know how that goes.

Sure. Then we have “My Love.” That one is interesting. You start off with something like an orchestra, and then head off into Afrobeats.

Yes. I love that song because that is not me. I like when I try new stuff. I sang the chorus, which is really not Sarkodie. I love to rap, and normally what I do is I do my choruses and call people in to come and sing. So that's what I did to that. As soon as I had the melody, I just sang the lyrics to it. It was like midnight, and if you listen to the music it has a very chilled vibe. The time of the day plays a part in how you record. This was around two in the morning. So when I did it, I sang the chorus first. I thought I was going to find somebody like I normally do. But the more I listened to it I thought, it's not really that bad. Let me just try and see. I was very nervous but I thought, let me just give it to them and see how that goes. People love it, and I love it as well.

Then we have “No Fugazy.” Because of the keyboards in that song, it reminds me a little bit of the Amapiano sound out of South Africa.

Yeah. Honestly, when I did that song I didn't know that Amapiano was in the system. I got the beats for this long ago. So big shouts to Rexxie from Nigeria. He is the producer, and he listens a lot to sounds so maybe he got the inspiration from there. Personally, I didn't know about Amapiano.

It was just a natural connection.

It was a very interesting beat. I thought it was commercial, but at the same time it commanded the prowess for rap. What I'm saying is a little bit like "Anything." People have to keep it real, no fakes. Especially with what you're wearing. If you don't have the money for Gucci you just go get some basic stuff. You can do your H&M or your Zarites. It’s still authentic. The fact that it's real, there's a lot of respect in that. For me trying to wear fake Gucci and fake Louis Vuitton stuck. So that's what “No Fugazi” is all about.

How about “Coachella”?

Coachella. A lot of questions came: why Coachella?. It's funny. But as creative people, we have these moments that are hard to explain. As soon as I heard the beat, the first thing that came to my mind was Coachella. I don't know why. Of course, I have never been to Coachella. I don't know what it feels like, but in my mind, the beats, the first scene that came the mind was Coachella. The tone has a festival vibe. Yes that's how come I named it Coachella.

There's that familiar melody woven in there that really took me back to my childhood.

Exactly.

It was one of the first songs that kids learn how to play on the piano. I think it’s called “Heart and Soul.”

I know the sound, but I didn't even want to ask the producer what song it was. I didn't want to know. I know, but I don't want to know. You get that?

I do. Anyway, it's a very interesting song. One more. Let's talk about the gospel song, "I'll Be There."

Ah, one good song that I really love. I've had that song for probably close to nine years. I wrote it way, way back but I felt that I was not mature enough to do that record. It was very huge. I was young. I used to write big, big records. I got someone to come and sing it, but I didn't really like it. So I just kept that song for a solid nine years and now I had the nerve to do it. I knew I could afford to get a choir, do this, do that. So this was the right time to do that song. I just linked up with a few people and put a choir together. I called my brother, and a childhood friend who used to live just behind our house, my mom's house. I never knew he was singing until I saw him on TV as well. He sings. He does gospel. So I brought into the house, and he organized the choir and made something beautiful and magic.

Shouts to Kaywa for the production. I love it. Kaywa is one producer that I go to when I need that classic, timeless record. He can give me that. And that's exactly what he did on "I'll Be There."

I have to ask you about one feature of your music, and that is in a lot of the new music, which is the use of obscenities and N-words, things that actually make it hard for us to plan on the radio.

[Big laugh] Yeah!

Well, you know, I think of Ghana as being a very Christian place, with a morally upright culture. And I just wonder how that goes down. Had this ever caused problems for you? Even just in terms of getting airplay?

Yes. A lot. I think the problem is – and I'm not going to say this is right, and I will definitely have to work on it – but I never came through the media. I was not presented to the people on TV and radio. I came through the back door. I used the internet, and the internet doesn't have a filter. So I used to say whatever I wanted to say, because I thought I was never going to be played on the radio. I just knew I was speaking to a certain type of people, and they listen to me, and that was it.

Even when I got successful and made it to commercial radio, I still felt like an underground artist. Even until today, I still feel that way. I've never had a label. I've never had people doing stuff for me. It's only me and my fans. So sometimes I have to even remind myself, "Yo, you're not that boy from the ghetto doing songs for people that you thought were listening to you. Now, you have different people open to your music, so you have to care more, regardless of how you want to see yourself as not commercial or whatever. You are commercial. Because people are listening to you."

So even when I was doing the radio rounds and people were playing the raw versions, I was in the studio and I was a bit uncomfortable. It's something I'm definitely working on. I think creatively, when I say that stuff I want to stay as raw as possible, but obviously we have to have the radio version, and as you said, I am from a country where morals are a high priority. So, yes, I definitely face a lot of problems, even family, and some of the new fans who appreciate the music. So definitely I'm working on that to make sure that moving forward we have songs that…. Of course, you never know where songs will end up being played. You can't take anything for granted.

So you actually make different versions of the songs, one that can be played on the radio?

Yes. We put out a clean version.

The last thing I want to ask you about is how much the industry has changed, and the business model. When we first started going to West Africa in the late ’80s, piracy was a huge problem. Artists couldn't make money off recordings, so it was all about doing shows. And basically, you had really great artists who could barely make a living. But now it's a completely different game with social media and YouTube and sponsorships and satellite channels. I'm interested in your take on this. When you started to think of this as a profession, what was your thinking about how you are going to make money? Did you think you needed sponsors? How did you approach the business side of things?

When I started, there were some stories that I used to hear from the big artists. What happened in the past is they gave you upfront money. That's what they call it. The give you upfront money, that's like your money that's going to be recouped from your sales. Depending on your gross capture, they're going to take it from your shows, your merch, everything. So I was up for it. Where's my upfront money? I was looking for it all over. I was trying to get my producers to take my music to everyone.

Fortunately or unfortunately, everybody was not interested in signing me, because I was doing records that were not radio-friendly. So for a businessman, they didn’t see it as something they could invest in. I was doing songs that had no horns, just kicks and bass, some weird stuff that I loved personally, but when it has to do with business, they did not want to work with me, because it didn't make sense.

So fast-forward: out of frustration, I had to go to social media. I built my following off social media. So there are advantages to the old system and advantages to the new system. What I think the old system had is an industry that was controlled. It was regulated. I don't think it was like a cautious thing, but the system was controlled. You couldn't just come out and blow up when there was no social media. So there had to be a plan strategically to try to build this person this year. So when they blow you up, all eyes are on you. You are the only person who can get the biggest check that year. It was easier in a way if you were picked. You didn't have to go through too much to be the biggest artist in that year, because every mechanism, the radio, the machine was behind you. It was like a cartel doing it.

And now with social media, the downside is there's a lot of music, so for you to stand out, you have to do something incredible that nobody has ever heard before. But also, you're able to build a following, which I really believe in because that's what my career has been all about. Someone told me not too long ago that I'm the only artist actually making money from music in Ghana. In a way, I would accept that, because I have a fan base who would actually go out and buy tickets or stream the music. My albums come out in leaks. But the fans will start tweeting, "Nobody should hashtag or retweet the leaked link. Let's buy it from Apple. Let’s buy it from Spotify. Let's support.”

So I've built a cult following, and I know how much I'm supposed to make every month. So for those type of careers, you’ve got a be good. I don't necessarily do too many shows, but streaming is something decent if you don't want to go over the top and be a superstar buying Bugattis and Range Rovers every time. You can be comfortable. So there is a good side to the streaming world, if you can really structure your business to suit it. I think we’re in a good time as artists. Just we need to sign up with the right organizations to take care of the money for us. And I think it's going to be good, especially if you’re independent and you have been able to build your following organically.

I think one big advantage you and your generation have over the old guys is that you can reach a much larger audience. Now there is media that plays in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania and so on. So that's a much much bigger market that you can talk to.

Yes. We love that. We thank God for that. I feel bad for some of my old guys. I know they paved the way for all of us. They kept it going for us to feel like we can still do it. Obviously people coming after us are going to do something way more than what we are doing. Now we have the world listening to everything, so you can always be lucky, find yourself in the playlist of even Obama. There's no limitations in how we dream at this point. I think now are very global, and doing songs and thinking some guy might be listening in the gym on his playlist. So we just dream bigger. We know we are talking to the world and not just Ghanaians.

That's got to be a good feeling. Great to talk with you. I hope you'll come to the U.S. to perform soon.

I'm always there. You know in lockdown, I was trapped in New Jersey for like four months. I was locked in Jersey City. As soon as I got there the airport shut down, so that's where I was. But I'm coming back. Definitely coming back.

We look forward to it. Great to speak with you.

Same. Thanks a lot.