“I was once described in a derogatory way by a journalist in England as a 'fan that had got his hands on a mixing desk',” Adrian Sherwood is fond of saying. “Honestly that's a very good summary of me really. That's what I am.” Sherwood's not wrong, exactly, but he's selling himself a little short. That seems to be his thing—well, that and a production sense that is both powerfully inventive and delightfully listenable.

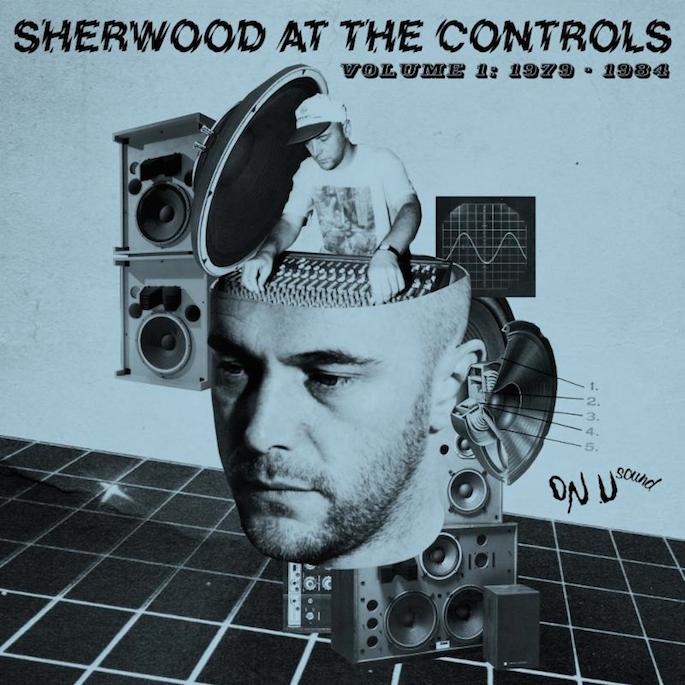

Sherwood says he isn't a musician; he claims to be tone deaf. He also says that he isn't a great DJ; he can't match keys or transition seamlessly, and has to get by on the rarity of his collection alone. But despite all of this, and despite not putting out a record under his own name until the third decade of his career, Sherwood's work has long been asking for a compilation. It arrives in the form of Sherwood at the Controls: Vol. 1, 1979-1984, on the very label Sherwood was founding at the time, On-U Sound.

As a producer Sherwood works at the intersection of reggae and punk, bringing together the giant shudder of sound system bass and instruments that live in space. He's a figure that makes sense coming at the end of the '70s and the beginning of the '80s. In America, bands like Talking Heads were leaving art school and forming groups whose approach was indebted as much to the visual arts as a childhood practicing scales. In the U.K., the London punk band Wire was approaching music like architecture. Sherwood, a fan of sound system music that had evolved from Jamaican roots into a full-blown subculture in the U.K., brought his own sensibility to production that was pliable enough to lead to a career of working with everyone from Lee '"Scratch" Perry to Depeche Mode.

With feet in the British punk and reggae scenes, he worked with the Slits. The groundbreaking punk band's track “Man Next Door” appears on the compilation. It's not that Sherwood's production rounds off all the Slits' rough edges, but that he teases out a slinky, sinister, cooler place in the band's reggae inclinations for his friend Ari Up's vocals to dwell. Likewise, you can also hear the development of a sort of proto-industrial style in these tracks, another genre where Sherwood casts a long shadow. It's a harsh, alienating sound that is particularly evident in his work with Shriekback, whose grumbling bass-heavy performance on "Mistah Linn He Dead" is far from the normal output of the usually much poppier band.

Based on a love of Jamaican music that dates back to a childhood spent listening to reggae and ska at house parties, Sherwood's production fits even more naturally with the few roots tracks found on the album. He finds extra dread (no pun intended, I swear) in Jamaican-born Prince Far I's track “Nuclear Weapon,” while pushing the envelope of backwards tracking on a track by Singers and Players.

To hear Sherwood tell it, among his many non-talents, he's also not a great businessman: too many drugs, too much debt. But he's been savvy enough for his label to survive long enough to release an anthology. The collection itself proves that what he lacks in acumen at an office desk was adequately offset by his mastery behind the mixing board.