For 10 years, the Algerian-French rapper known as Saïdou was a member of the group Le Ministère des Affaires Populaires (the Ministry of Popular Affairs) or simply, MAP. A hip-hop group based in Lille, in the north of France, they were highly influenced by the music and culture from the region—a bit of Algerian, a bit of Jacques Brel, a touch of Balkan, American hip-hop, and a political/social agenda from groups they idolized, like the French band Zebda. Saïdou has described MAP as “anti-racist, anti-imperialist, anti-colonialist and anti-system.” They eventually splintered into another group with Saïdou forming Le Zone d'Expression Populaire (the Zone of Popular Expression), or ZEP, which caused a controversy with their song, “Nique la France!” in 2010. The band was sued by an extreme right-wing group who claimed the song was racist against white French people. Many international celebrities signed petitions in their support of the band and the ensuing legal battle brought needed attention to racism in the country.

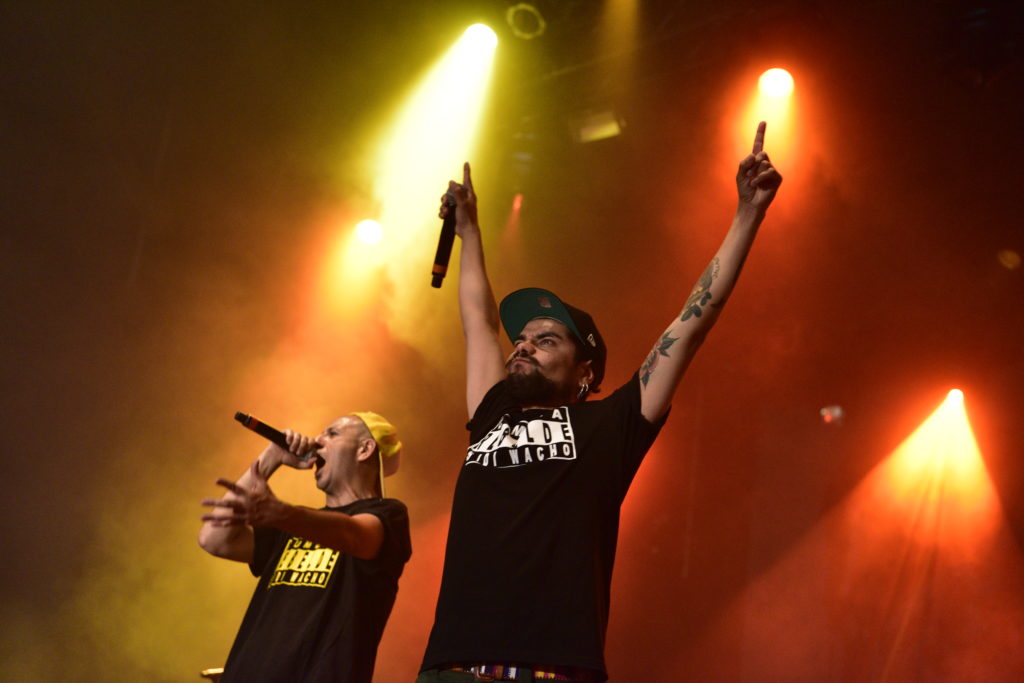

Saïdou's latest group, Sidi Wacho, continues his exploration into mixing musical styles and rapping about social/political issues, but this time adding a South American twist. We spoke with Saïdou backstage at the Festival International Nuits d'Afrique de Montreal after their sound check, through an interpreter.

“I could write a whole book on how I discovered music,” Saïdou says. “I started music as a kind of identity rebellion. Questioning cultural identity has been an issue in France for some time—race, culture, many things in this area. And as a musician, I'm very interested in this as an immigrant of working-class background, especially as we are the children of the former French colonies.

“Lille,” he continues, “is different from other parts of France because there is a large mix of North Africans. MAP, like Sidi Wacho, dealt with social and racial issues. The difference with Sidi Wacho is that now we have introduced a Chilean artist into writing and creating the songs, and he brings similar issues from his part of the world into the mix.”

How Chilean rapper Juanito Ayala came into the mix began when Saïdou decided a few years ago to go on a trip to South America.

How Chilean rapper Juanito Ayala came into the mix began when Saïdou decided a few years ago to go on a trip to South America.

“It was a voyage, not a vacation—a political voyage,” he explains, “because I was very interested in exploring the connection between the two continents—North Africa and South America. Both are in the Southern Hemisphere and I was interested specifically in learning about the indigenous communities and how they were both colonized by Europe. I knew a little about the history of South America because I am always interested anti-imperialism and anti-capitalism. What surprised me was how much the American capitalism and neo-liberalism—the Coca-Cola, McDonald's—had spread there in a negative way.

“So while I was in Chile,” he continues, “just by chance, I had heard Juanito's music on the radio at the hotel I was staying at. So I asked someone who worked at the hotel who that was and then I went to a small street concert where he was playing. He knew about MAP and my music. A week later, he invited me to do a song at his next concert. Then we met a third time and just messing around writing a song together. I didn't go there for the reason nor with any thought that I would be forming a new group on this voyage. It was just to explore the people, learn Spanish, and record some music for ideas. I thought I was on a break from doing music.”

A year later, he returned to Chile and the two wrote a few songs together and thought they should try to record some of them. So Juanito came to France and Sidi Wacho was born. Saïdou brought in two members of MAP—accordionist Jeoffrey Arnone and Balkan horn player Boris Viande, and who were joined by French Afro-Cuban percussionist Fred “El Pulpo” Savinien (who's played with Toots Thielemans and Carlos “Patato” Valdés, among others), and Chilean DJ Antu. The name Sidi Wacho itself announces the cultural mix of the group with sidi being the Arabic equivalent of “Mr.,” and wacho, slang for a street kid in Chile. In most of their songs, Saïdou and Juanito take turns rapping, the former in French and the latter in Spanish.