In preparing the program “Journeys With the Oud,” Afropop’s Banning Eyre visited Palestinian composer Simon Shaheen, an oud and violin virtuoso. They met in Shaheen’s Brooklyn apartment on a snowy, February afternoon in 2003. They had spoken many times since meeting in 1995, but this time, the focus was on just one subject: the oud. Simon is a master oud player, but he began by protesting his shortcomings as an informant. Nearly two hours later, he had more than fulfilled my hopes. Granted, this is one man’s view of a complex subject, but it is a rich, passionate discussion of the instrument and its music, full of insights that only a player could provide.

Banning Eyre: What do we know about the origins of the oud?

Simon Shaheen: I’m not a historian. This is not my forte. But we know this is one of the earliest instruments. It is the father of so many instruments that came afterwards in Asia and in Europe and in Africa. I know from some photos that I saw in some museums that the Persians who were captured during the Arab Empire and Persian Empire, they brought with them the oud as we call it now, but I know that the name was barbat. It’s interesting that it looks like the oud, but the top was made of skin, and it had fewer strings. I assume it was like three strings. I also read that the barbat was carved from a single piece of wood, not made from laminated strips like the oud.

I wouldn’t know that. It’s possible. So many instruments are carved rather than laminated, but what’s interesting is that the oud under the Arab Empire, especially in the Abbasid period [8thcentury onward], it reached very, very complex situations in which it became the central instrument for singers, for performers, for the entertainers at the khalif’s chambers. This is the exact oud that was modified from skin top into a wooden one, from three strings to four and later five strings. This is also the instrument they had when they conquered North Africa and Spain. We’re talking about the early 8th century. Many musicians moved there, especially Ziryab [a highly influential musician in Andalusia], and they took with them the oud. This is how the oud penetrated through the Spanish and southern French peninsulas.

Later becoming the lute and laoud, as they call it in Cuba.

Laoud, yes. Al lute. Yeah. I’ve spoken to many musicians who play European early music, here and in Europe, and they are all familiar with the notion of the troubadours playing the oud, you know, the nomad singers who moved around France and Spain. They learned it from the Arabs in Spain, so you have the lute and all these instruments that came later on in Africa and in South America. I mean, don’t they have it in Cuba? They do, and it’s almost exactly like the oud. It hasn’t changed much.

You were talking about the Abbasid period. Tell me a little more about that,

I mean, here we are talking about the center as Baghdad. But we are not talking about Baghdad under Arabs. You are talking about Nebachadnezzar, the Akadians, a much older civilization. About this, I don’t know. But from what I’ve seen in museums, from what I’ve read, and from what I’ve heard from both Persian and Arab musicians, this is how they think the oud emerged in the Arab world.

But what’s important here is that the oud became the central instrument and became so developed and so interesting under the Arabs. That’s what’s important for me. They pushed this instrument to the highest possible level.

When we get to the Andalusia period, a very rich period culturally, was this a key time in the development of the oud, or had that already happened when the Arabs came into Spain?

No, no, it was still developing. Because even in the 20th century, many oud makers were still experimenting and inventing many things. For example, if you look at the oud Munir Bashir [an Iraqui oud master] used to play on, it’s not exactly like the traditional oud we know in Egypt, in Syria, the Levant area. Instead of having the bridge on the top, which is the face, and hooking the strings into that bridge, he had a moveable bridge, and the strings were hooked to the back of the oud, which we call tassih. That’s the back. I’m talking about the part where your right hand goes over the back, which is the bottom of the oud. This is where they hooked the strings. The sound of the oud also changed. There was less pressure on the top of the fact itself, because when you glue the bridge on the face, with the tension [from the strings], this bridge is pulling on the face. I know of many instances where if the oud is not made well, the bridge on the face, breaks away, or else the part between the bridge and the rosette curves in. So [the Iraqis] pulled the strings to the back of the oud with a moveable bridge placed on the face. It’s like the lute or the guitar, the same concept.

But again, these are experiments. There are people who have added a sixth and seventh strings to the oud, enlarging the range incredibly. There are technical issues, why they are adding strings.

I read that there are two main schools of oud construction, one Turkish and one Arab. Is that generally correct?

The oud in Turkey is the same as the Syrian oud. This is where they got the idea. It’s the same. I know it’s the same. The only difference is that a Turkish oud is that it’s a bit smaller in size. As far as the construction, it’s the same.

Five pairs of strings is the most common, right?

Yes, five pairs and one single drone bass string, like what I am doing. Also, the beams they put under the top, probably in Turkey, it’s a little harder and face is a little thicker, because the way they tune the oud in Turkey is one step above the Arabic tuning. We have the G as our reference. The same string for them would be the A. The pitch is very important.

What is the lowest and highest pitch you find today?

In the Arabic tuning, they sometimes add a higher string. Mine, for example, the highest would be C. Many musicians add the F, which is the fourth above. So this is a lot of tension, right? I notice that in many instances musicians add the F string because of [lack of] technical abilities. Instead of playing on the fingerboard of the oud, instead of using different positions up and down, they would rather stay in one position and then use the F string. They prefer to stay in one position and play the higher notes on the F.

Like if you listen to “Blue Flame,” the title track, it has this very fast, virtuosic opening. It’s all over the finger board and the face of the oud, reaching up to the rosette with very, very difficult runs. So this could be done this way if you want to learn it this way and you have the talent and the ability. Or it could be done by adding an F string and you can make it in one position instead of moving up and down. But for me, adding the F string does two things. First, it limits the technical abilities of the player, as far as covering the fingerboard of the oud. And two, this string absorbs the players into one, two, maximum threemaqam (scales). It sucks them into playing always on F minor, F major, or F rast, which has the third as a quarter tune. F, G, and A half-flat. O.K.? Because you have this open high string tuned as F, right away it absorbs all the playing into these ranges. So what this additional string did was to limit their ability to improvise and modulate and use so many intricate maqams in the lower ranges of the oud. I think this could be catastrophic.

That reminds me of Malian guitarists using a capo to raise the pitch. Some say it prevents players from learning the fingerboard in higher positions.

Yeah.

But all this modification comes in the context of the oud having become the central instrument in Arabic music. Let’s talk specifically about the Andalusia period. What can we say happened to the oud during this period?

Actually, we have a lot of historical material and literature filled with descriptions and photos, but unfortunately we don’t have much written music that was left, and of course no audio and visual documentation. But it’s simple. It’s easy to tell because of many styles I’ve heard played on the oud, and other instruments like quetra in North Africa, the style of playing which is closest to the Andalusians. It’s possible to detect that already it was very developed when they played the oud in Andalusia. It would be very strange for me to think that the lute emerged from the oud at that time—we’re talking about the 8th-11th centuries—[if the style were not already advanced.] You know the lute has its own character and technique of playing, so I don’t think this technique came out of the blue. It has to have a kind of reference. So you can make a connection there.

And knowing from the vocal repertoire—which we still have, and this was the main central repertoire in Arabic music—and the intricacy and the complexity of it, you could tell how technical and complex it was playing on the oud at that time. Because we have a lot of muwashshah, this is the Arab Andalusian vocal repertoire, which up to today is the most complicated and the highest repertoire in Arabic music. If you look just at the melodic constructions, with so many modulations [or key changes] that they went through in one piece. This is one thing. Then you look at the rhythmic intricacy, the use of cycles of 10 beats per cycle, 14, 17, 21, 34. In the retreat [Simon conducts an intensive musical retreat every summer], I teach students how to sing one phrase of muwashshah, let’s say 14 beats per cycle, and how to clap and play the rhythm at the same time. So let’s say we’re taking a cycle of 10 beats, which we don’t find very much in Western music.

[He demonstrates, counting 10 beats and clapping on 1, 4, 6, 7 and 10.] The 4 and the 10 will be like the off beat, this is why I’m using the back of my hand. So when I clap straight, this is the down beat, 1, 6 and 7. 4 and 10 will be the up beat, which is the lighter beat. [He sings a musical phrase while clapping.] If they did this, we can imagine that music was very intricate, very highly developed. So I believe that the oud reached its highest [in Andalusia]. It was used by composers, by top performers, and this is exactly what many Arabic composers in the 19th and 20th century used, in what they call in Egypt the Arabic Music Renaissance.

I’m intrigued about what you were saying about the Early Music in Europe. What would be the history of those troubadours you referred to?

You know, Early Music, you think about the 12th, 13th, 14th centuries. The Arabs left in I believe 1471, so we are talking about the 15th century. That’s after at least 4-500 years of presence. Think about Cantigas. I did an experiment with an Early Music group from Boston. We played at the cathedral in Washington. The repertoire concentrated around the Cantigas of Santa Maria, and you listen to these and you could feel, rhythmically and musically, in the character of the music, its relationship to vocal repertoire of the Andalusian period. If there was not this period, there would have been no Cantigas. It’s as simple as that.

So when I played with them on the oud, it sounded very natural. Now the troubadours; we’re not talking about Cantigas here. I have heard recordings of music that emulates the troubadours, but how would I know if this is exactly how the troubadours played or not? What I do know from pictures I have seen is that they used the lute, the oud. It was very much the central instrument in their music, and also something similar to thenay, the Arabic flute, and the tambourines, which we call riqq in Arabic, or daff. And the troubadours were nomads. They moved, like gypsies, like the Bedouin in Arabia. They used to move constantly because of their environment, so there is great support for the idea that they learned the Arabic music in Andalusia and then toured with it. No doubt in my mind. Probably what they did was instead of Arabic lyrics, they used French or Spanish lyrics. I read something that said their lyrics had many Arabic words. If you listened to it as an Arab, you might not understand it very much unless you listened carefully, and detected the Arabic words.

That’s fascinating. I don’t think this is well understood by a lot of people, the infusion of Arabic ideas into European music, and then by extension New World music. The Cuban story is particularly fascinating to me because Cuban music emerged as such an important starting point for 20th century popular music, and yet it contains remnants of this period. We went to Cuba and visited the home of a player of laoud. It’s so interesting to contemplate how that instrument that arrived here.

Yes. Now, the other point that I can invoke here is the concept of the quartertones, or microtonality. The easiest way for a listener to understand the concept of microtonality is to think about the piano, two keys on the piano which are next to each other—white and black. You play the white and the black and you hear the pitches and your ear can digest it. But imagine that there are two or three keys between these white and black, qualities of pitch that are in between. This is what we call microtonality and the ear can listen if it’s trained to, if this is part of its culture, like in the Arab world, in Turkey and in Persia.

But I have heard vocally in much of the music that comes from, for example, Ireland, and in much of the music in Spain today. It has microtonality. Definitely. No doubt. When they play the flute in Ireland, there are certain pitches that have microtonal quality, and this is how they hear it. It’s not that they are playing unfortunately out of tune, as many Americans think. It is quality, pitch quality. They are capable of hearing it and it is part of their musical education.

So we know that in music in Europe, way before Bach, there was so much music that used this microtonality. I can hear it. There was a period when some musicians came and said, “O.K., we have to simplify this music.” We have to make it into a science. So do you keep it the way it was? Or do you restrict it to get rid of microtonality, saying, we have only two systems: major and minor? Then take the modes out of those and build the harmonic structure. Bach, for example, was one of the champions of this notion, getting rid of microtonalities in order to establish this harmonic structure.

This was the idea of “temperament.”

Yes, the well-tempered clavier is the best example.

It’s interesting to think of that as an attempt to eliminate this characteristic of music that had existed before. When I learned about equal temperament, I thought of it just as standardization, not in terms of redefining what was correct and beautiful. I’ve since encountered people who are very much in rebellion against this. A guitarist in Colorado comes to mind. He has made a 19-string guitar in order to get the characteristic microtones of different music found around the world. He thinks that the current “world music” movement is dangerous because it is forcing equal temperament and standardization on tuning systems around the world. I’ve certainly encountered this in Africa, making tuning adjustments to traditional instruments so that they can play along with guitars and keyboards.

Yeah, this is a big issue. I write a great deal about this, and I talk about it. I’m not saying here that the Western classical music in the 16th, 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries was not great music. It was. No doubt, no doubt. Making those decisions created a period of 250 years of great music, no doubt. But now, I can tell as a musician and thinker that there is definitely a limitation to this. I mean, how far can you push it? Think about the experiments of the late 19th and early 20th century in Western classical music, European music in particular—trying to change the whole structure, the scales and the harmonies. Intellectually, they were great experiments, but if you come to translate these intellectual [ideas] into our behaviors as listeners, our acceptance, our love of art, it wasn’t accepted. It was a big failure, right? And this is why we are witnessing today a huge bankruptcy in what we call classical music in the Western world. So we still go to concerts and listen to orchestras and chamber ensembles and soloists playing still from the same repertoire, over and over and over. It’s seldom that you hear a contemporary piece. So I believe this is a price we paid for this. But on the other hand, there was a period of history that came up with great music. We can’t ignore that.

Fascinating. Coming back to the oud, from a player’s point of view, how do you use microtonality?

It’s an open fingerboard like on the violin or the cello, so it depends on where you press on the string. So let’s say you decide that you want to use an area on the finger board of two inches. In these two inches of the string, you can have so many sounds. When you move your finger little by little, each time you move it you are getting a different tonal quality in terms of pitch. There are infinite possibilities that you can produce out of an open fingerboard. But this alone wouldn’t be the answer. You need the theoretical system that will inspire you and guide you to what you want to hear and produce. So this is why we have the maqam system in Arabic music. Maqam—think about it as the modal system or the scales, like in jazz music or Western classical music. So you have many maqams because of this microtonal quality.

Between white and black key on the piano you have a half-step, and between white and white you have one complete step. But now, instead of having just half and whole, you have the quarter and the eighth, and it opens the whole horizon in front of you. So based on the maqam system, we can create compositions and improvisations, what we call taksim in Arabic music. You see the maqam on the fingerboard, and interestingly enough, in many treatises of the 10th, 11th, 12th centuries by great Arab philosophers like Ibn Kaldun, like Al-Kindi, they took the tambour, which is like an oud with a small body and a long fingerboard like the bouzouki in Greece, and they divided the frets on the tambour according to the fret structure. In other words, this division on the fingerboard indicated the maqam. You can keep it open, or you can put frets. [Because the neck is so long,] you can put as many frets as you want, for quarter tones, even eighth tones. They called each fret by a name. This is how the theory developed. It’s not that the theory developed, and then they put the frets. No. So the fingerboard on the oud determines much of the theory. But when it comes to the idea of composition, the creative process, you want to establish the idea of the maqams, and you revert to them as your theory.

We’ve spoken before about improvisation. Because of all the freedom you have as a player on the oud with its open fingerboard, you have a lot of responsibility, and one might even say, danger.

Of course.

So that’s very different than what you have available improvising, say, in jazz.

Just to say a couple of things about this concept of freedom. I mean, this is very dangerous. Freedom. No, there is no such thing as freedom. What we are talking about is the freedom to use the maqam system, as opposed to the raga system in Indian music, or the use of the maqam in Persian music. In Persian music, there are established modal ideas that are very traditional and that you have to follow when you improvise. You can’t do much modulating. In Indian raga, there is no modulation at all [that is, no changes of key within a single piece] if you play classically speaking. The modulation is rhythmic. The piece starts slowly and it evolves. But in Arabic music, it’s the opposite. It is the knowledge of the maqam in so many intricate ways that is considered excellence.

But you don’t call that freedom?

No. Unlimited, yes. But this is not freedom. Freedom is an irrelevant concept here. There are rules in the use of the Arabic maqam system and there are rules in Indian raga. The Indian system limits the classical player to one raga, and the Arabic tradition doesn’t limit. It limits the musician only to the use of the maqam system in its rich and vast possibilities. There are limitations in both, because there are the traditional rules about how to perform a classical taksim or improvisation, as in how to perform an Indian raga improvisation. So the fact that we use a lot of modulations does not mean that we have freedom. It’s almost the opposite.

Those possibilities create demands.

It’s tradition. If you grow up with this, or learn this and digest it well, you will know how to do it. It’s like any culture. But you were asking about improvisation in the jazz world and in the Arab world.

Yes.

Let’s limit to the Arab world, because I have to be careful here about improvisation for example in the Levant area, because there is this connection between Egypt, Lebanon, and Syria. This is the region we’re talking about. In jazz improvisation, there are a lot of similarities, the freedom for a player to express musical ideas at the moment of playing. This is common, right? The question is how creative you become? What is the freedom you have? And the idea of the use, on the one hand, of the jazz scales, which depend very much on Western classical music, and the use of the Arabic maqam. So we agree that in both there is improvisation, creation in the moment of performance. In jazz, we hear now about “free jazz.” But traditionally speaking, no, you can’t just play free jazz. It has to correspond to a certain harmonic structure. For example, they play a theme of say 16 measure, and these 16 measures follow a particular harmonic structure. The player has to keep to this cycle of 16 measures, to abide by the harmonic structure. While in Arabic music, taksim or improvisation, first of all, there is no harmonic structure that you have to abide by. You have a vast amount of maqams that you can use in your improvisation.

But you can’t just say that I am using this maqam. No. Each maqam, or mode, has many small components. In Arabic, we call them jintz. This is a type of grouping. You have these small groups of pitches within the maqam that create a particular type of sound. This is the artistry in Arabic music. It’s not that you are moving from one maqam to another. It’s more intricate. You are moving from one jintz to another within the maqam itself, and between maqam. This is the intricacy. This is a very, very difficult issue. Imagine that you have 10 maqam and each maqam has four, five, six, maybe seven jintzes. You can play within the maqam itself and make your modulations by using the jintzes within that maqam. Or, you can use one or two with maqam A, and then move to some other jintzes in maqam B. This is the artistry of improvising in Arabic music, how you make these connections.

This is the thing that makes Arabic taksim so powerful and so highly respected. O.K., we don’t have harmony and harmonic cycles. We don’t need all this. But what we have are the rhythmic pulses within the improvisation. It can be very free and open, but still you have rhythmic pulses, and there are so many rhythmic patterns that coincide with the jintz of the maqam you are playing in. And then you have the idea of embellishment—ornaments.

I remember when I was at the Manhattan School of Music and they were teaching a class about ornaments. I stood up in the class and said, “May I add something about ornaments? I’m going to take a movement of a Handel sonata, and I’m going to ornament it on the spot, with the violin.” And I played it with ornaments, and everybody was like, “Oh god, what’s happening here?” These students knew music very well. I mean, imagine students going to Manhattan School of Music. Very established musicians, but their mouths hung open. “What’s happening? What’s ornament? What’s embellishment?” They had no clue of what is an ornaments. Ornament was a key component in European music in the 14th and 15th and 16th century, but there is no such thing now.

We have these groups that play Early Music, and they use ornaments, but for me, it’s interesting. Either I don’t understand how they are using the ornaments, or they are not convincing me. I don’t know. It doesn’t sound like a natural element embedded in the music they play. It sounds like you are imposing an ornament on a line of music. While in Arabic music, there is no such feeling. Ornament is part of the structure of music. Who plays Arabic music without ornaments, it’s like dealing with a skeleton.

Let’s talk about feeling, the emotional side for you as a player, and particularly regarding the oud. I’m trying to imagine the kind of improvisation you’ve just described, taking these jintzes from one maqam to another. What can we say about what guides you not on the intellectual or theoretical side, but on the intuitive, emotional side? This is probably an impossible thing to talk about, but is there anything you can say?

No, no. This is very much something you can talk about. I teach this to students. Last August, we did a class on maqam and improvisation, and I brought students who never touch maqam and improvisation, put them in front of all the students and asked them to improvise. It’s always viewed as an untouchable concept, something from Arabic mythology. [Simon laughs.] No, that’s not true. Improvisation and taksim in Arabic music is a learnable thing. You can analyze it fully, and you can learn it. But you can’t learn it as many people want in one or two years. They think of this music, first of all, as ethnic music. Right away, it’s down there. And then, they say, two or three years is more than enough. There is no such thing. This is a lifelong process. Nobody can do a real improvisation without learning this music for 20 years. It’s as demanding as Western classical music.

When you’re at that level, what does it feel like? What is it that’s guiding you when you aren’t thinking about the theory because it’s already inside you and you’re doing it on the intuitive side. I don’t want to put words in your mouth. I want you to try to articulate the experience.

You did already. O.K. Here, we have to analyze what is a good musician, a good player, and a good improviser. So you have the musician and the player, and improviser. Because there are many good players who are not great musicians. There are many great musicians who are not good players. There are many good musicians and players who do not know how to improvise. It’s very clear. You know what I mean?

Well...

You are not getting it. For example, Riad el Soumbati, one of the greatest musicians in the 20thcentury in Egypt who composed all these master vocal pieces for Oum Kalsoum. Any great composition by Oum Kalsoum, especially in the ‘40s and the ‘50s, any great vocal composition, I can guarantee that it was composed by Riad el Soumbati. This person was a great composer. He was a great musician, and he was a great oud player. So the fact is he was a great oud player and great musician, and he also improvised beautifully on the oud, although more in the traditional sense. Let’s take Wadi el Safi [the 80-something Lebanese singer featured on the 2000 album, and the Afropop program “The Two Tenors of Arabic Music”]. Wadi el Safi is a great performer as a singer, but I wouldn’t say he is a fully great composer. He’s excellent in relation to his voice and the environment he grew up within in Lebanon. As a performer and musician, he is the greatest, or one of the greatest. He always accompanied himself with the oud, and he played beautiful oud, but he wasn’t a great improviser. He did the very short, traditional improvisation, just to prepare himself to sing. But he didn’t take the oud to a higher plateau and become a great improviser. No.

So it is possible to have these things. You know many Indian musicians who are great performers and musicians, but they are not great composers. This is also possible in Western classical music, isn’t it? What about Sabah Fakhri [the other singer in the Two Tenors project]?

He plays oud, for example, but he can’t improvise on the oud. He is a great vocalist, a great musician, but he cannot compose. So as far as taksim, or improvisation in Arabic music, you have to have the three things I mentioned. I am speaking of the whole being as a musician, your education in music, your sensibility, your knowledge of the repertoire traditionally. If I talk to somebody and I say, “Do you know this suite?” No. “Do you know this vocal composition?” No. “Do you know Abdel Wahad Mohamed?” No, I’m not familiar with this. So how will somebody be a great musician if he doesn’t know the great repertoire? And how are you going to get the ideas and the maturity to become a great improviser if you don’t know all this? You must know it. There is no other way.

So musicianship is very important. Virtuosity in playing is very important. Here, I can contradict myself and say virtuosity is not everything, because in Arabic music, if an improviser is virtuosic, great. But in the first place, they should have the sensibility. It’s not a requirement to be a great virtuoso in order to improvise. For example, a violin player who played with Oum Kalsoum. He accompanied her from the beginning of her life until the end, Ahmad al-Hafnoui. Technically, he didn’t have anything. He wasn’t Heifetz. But, when you listen to a few notes from his playing, it makes you melt. So it’s not a condition to be a virtuoso player with the violin.

You can do so much with the tone on a violin.

Yeah. You don’t have to be a clown, up and down and fast. It means nothing.

No, not if you can make that singular, personal tone.

Yeah. You know right away it’s him. And there is a beautiful sweet quality that comes out of his violin that nobody can do. There are so many violinists who are way better players than him in Egypt, right? But nobody has the character, nobody has the musicianship, nobody has the tone that he could produce.

The violin is so open to that, almost like a human voice. Some horns have that too. But what about the oud? How does it compare as an experience? Can we say the same thing about the oud?

Of course. The same thing I mention on the violin can be applied to the oud. Again, you have to be an excellent performer, to have virtuosic ability. Why not? But don’t let virtuosity preoccupy you, like what’s happening with a lot of players today. They are concerned about how to make a certain run on the oud, and how to sound like you are a virtuoso. It’s nonsense. I mean, I have technical ability which is unbelievable, but I will never let my technical ability dictate what to play, how to produce sound. I don’t know if you came to Joe’s Pub when I played for APAP (Association of Performing Arts Presenters). I just played a taksim. To somebody who has no patience, it was very draining, slow. It was very interesting. So this was one aspect of me.

Was that premeditated? Or did you just feel that way?

I felt that way. I love it. It was great. Then I played another piece on the oud, like “Blue Flame.” It’s a virtuosic piece. But you don’t let this virtuosity and technique occupy you and direct you to how you should sound. So, virtuosic or not virtuosic, you have to be a good performer. And I give you the examples of Ahmad al-Hafnoui and Riad el Soumbati. You have to be a great musician, understanding the whole repertoire of this whole musical tradition. And the third thing is to have the talent for improvisation. It’s impossible to disconnect the three things from each other and say you can improvise. Improvisation as a medium has its own merit, but if you are a great musician and performer, let it be. That’s great.

And this is how, when you improvise, you are talking about how you establish the mood. It is the three things that I mentioned, and then the knowledge of the maqam system, but beyond that, it is an understanding of the emotional quality of each jintz within the maqam. O.K.? Like if I want to improvise and I want to transcend to you certain sad feelings while I am improvising, I can do this, by the way I play, the understanding of the playing and the choice of the jintz within the maqam. This is how I convey to you certain musical vibes.

When we talk about the modern history of the oud, what do you feel that you and your work has contributed to the development of this instrument?

First of all, it is able to bring the oud to the center stage, symbolically, to have followings, to have an audience who will come to listen to you as an oud player, which was unheard-of, let’s say 35-40 years ago. Because the oud in the whole tradition of Arabic music was always the main instrument in the takht, or small ensemble. It was a main instrument in larger ensembles, like an orchestra—10, 15 musicians. It was the closest instrument to a composer. Whenever a composer wanted to compose, he used the oud, like the piano in the Western musical world. And the oud played a great role as a solo instrument, but within the context of the vocal repertoire. You got me here? For example, if you take a vocal suite, which has so many intricate structures within it. The oud was an important drive in this suite, and always when there is an improvisation or an instrumental piece, you see that the oud is the leading instrument, and the kanoon, but the oud more so. So the oud was a great instrument. It has great abilities, but it was captivated historically within the vocal repertoire, because if you listen to Arabic music as tradition, I would say that more than 93, 95 percent of the music is vocal, and the rest is instrumental, and most of the instrumental is the improvisational part.

And this is what I myself started to do since I started to perform on the oud. Instead of playing a traditional improvisation that lasts a minute or two, maximum three, I started to play an extended improvisation that might last 15, 20 minutes, and I do this in my performances all over whether it’s in the Middle East or in American or in Europe. Then I do compositions for the oud that utilize the abilities of this instrument. I mean there are so many intricate abilities. If you don’t show it, then nobody will realize it. But show it, and it will be another expression of the instrument. It’s there. So I did this in my compositions. I composed pieces for the solo oud, both within the traditional repertoire and within the more fusionistic repertoire.

And you know, the way I played on the oud, it opened the whole frontier in terms of the technical abilities of the instrument, but again I want to emphasize that the technique is not the drive behind it. But the technical abilities are interesting. If it’s possible to express something using this technique, then let it be. That’s fine. So this is basically what I did with the oud, and I covered the different styles of playing and literature. In performances and recording I do a very traditional style of playing, then I do more the contemporary Simon Shaheen playing, and I do the fusion, the interaction with other musical cultures and concepts.

Finally, I’d love to get you to tell me what you can about these other oud players. [I hand him a pile of CDs I’m considering for the program.]

George Abyad. I’ve heard him once or twice. It is more the traditional style of playing. He is Lebanese. He’s the one who plays more like instrumental pieces from the Arabic and Turkish repertoire. Like I see here the introduction to a song by Oum Kalsoum, “Nagh El Borda.” And then there are, for example, a Turkish composition, “Semaie.” “Shat Araban” is the mode. So it’s pleasant, it’s traditional, but very basic in terms of improvisation.

Let’s talk about these Iraqi musicians. We have Munir Bashir and his son, and this young player Naseer Shamma.

Munir Bashir—I know his playing. This is more the Iraqi school of playing the oud. Now, when we say the Iraqi school of playing the oud, it’s not necessarily pure Iraqi. We are talking about the Iraqi musical tradition coinciding with the Turkish way of playing, because there were two excellent Turkish, musicians who came to Iraq and established the school of playing the oud in Iraq. We are talking about the 19th and early 20th century. So what the Iraqis, people like Munir Bashir, did was they took the technical aspects of the Turkish way of playing on the oud, and some of the ahank, which are the musical pulses, not exactly ornaments—colorings, if you will—and he applied them to the Iraqi style of playing. So it was a matter of combining both Turkish technique and color with the Iraqi traditional vocal instrumental style.

But actually, if you want to listen to a really impressive performance, you should listen to Munir Bashir’s earlier recordings. Listen to something in the ‘60s and early ‘70s. I met his son [Omar Bashir] in Greece. I was giving a workshop and there was a gathering of instruments from around the Mediterranean, and I heard him playing. He is very much a replica of his father, very much influenced by his father’s playing. He has good abilities, but we ought to see in the future how he will develop. But Munir Bashir as a player, definitely he was a fantastic player, and of course, he improvised a lot, and he utilizes both worlds, the Turkish, the Iraqi. He uses very much the Iraqi maqam. When we say the Iraqi maqam, it’s not necessarily the scale system. The Iraqi maqam is something like a suite. They have very structured compositions called the Iraqi maqam. And each suite has its own modal structure and forms. So he used this in much of his playing and in some of the pieces he composed. He had his own sound. It’s very important that we listen to somebody you know it’s him. This is his sound.

O.K., [Naseer] Shamma. I heard him one time. He comes from this school, imitating Munir Bashir and this kind of thing. I don’t know what his relationship with the improvisational world is, because I didn’t hear much of the improvisation. But he composes things like imitating sounds, like sirens, or natural things, you know? But I don’t know much about his repertoire. There is one dramatic piece in which he evokes the air-raid sirens. He’s doing the bombing of Baghdad.

Really?

Who else do you have?

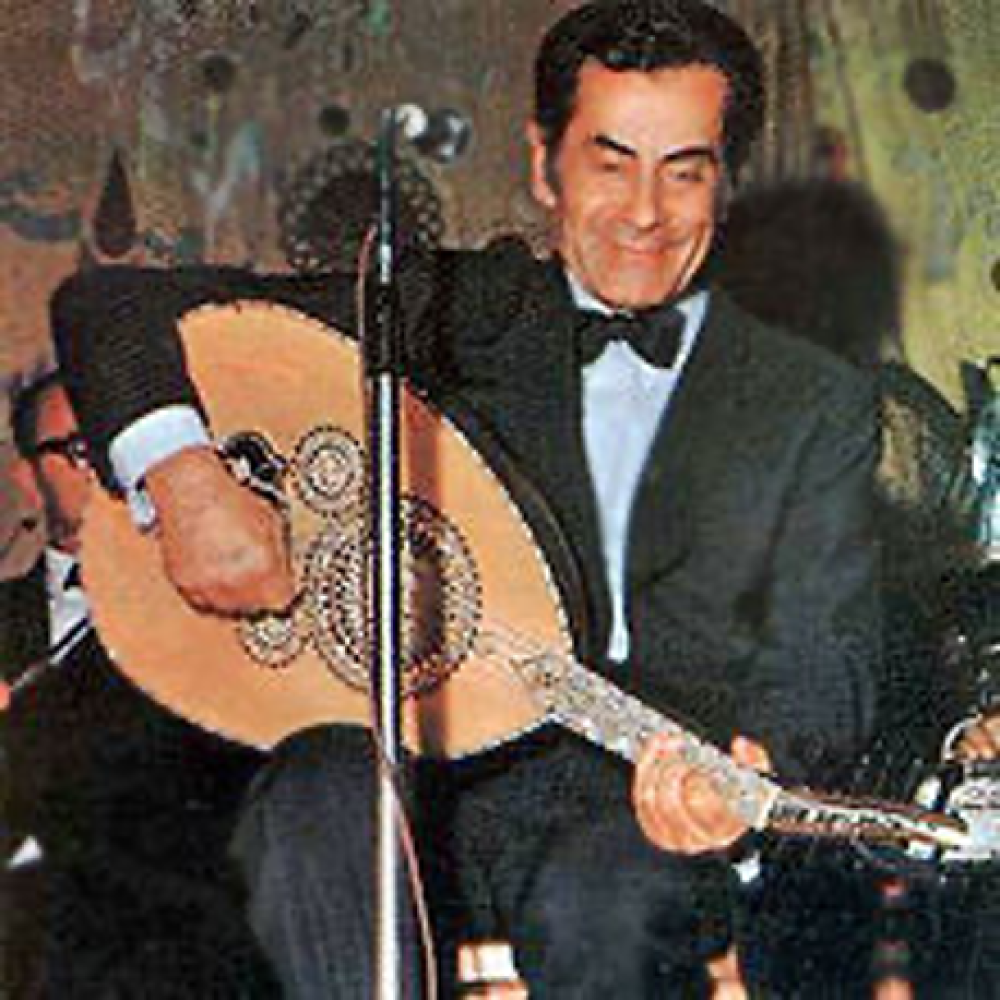

Farid El Atrache.

But again, you are listening to Farid el Atrache when he was late. You want to listen to early Farid el Atrache. He is Druze, between Syrian and Lebanese. It’s in Lebanon but it has a lot of the Druze culture and the Syrian. So he is more Syrian, originally. But most of his artistic life was in Egypt. This is where he flourished as a singer and oud player and composer. He was an example of a great oud player who accompanied himself as a singer. That’s unusual, and his playing is unbelievable. He wasn’t a person who could do a concert on the oud, because he was more involved with his singing career and composing vocal music, but in every concert he performed, he always did an improvisation in the beginning on the oud, and I’m talking about an extensive one, like 10 minutes, like 12 minutes. So if you listen to some of his early recordings, you can detect how great he was. He reminds me of Jorgo Bajanis [this spelling may be incorrect] of Greece and Turkey when he played at Istanbul Radio accompanying singers. Right away, you hear his playing. He was great, unbelievable. And Farid el Atrache—the same thing. Such beautiful playing, great technical abilities, and the most important thing is his right hand—unbelievable. It’s crystal clear, and the tremolos he did. Fabulous!

How about Marcel Khalife’s oud duo, Jadal?

Yeah, Marcel Khalife. Jadal. Marcel is a very sweet, fantastic oud player. But it’s important for you to listen to him when he performs alone. Marcel is very much into the composition. Play or execute exactly what is on the page. He is into this. You know, Marcel started as a singer and oud player and then he started to compose, and he has composed so many vocal compositions, from love compositions to nationalistic compositions.

There’s a strong romantic quality to his pieces.

Yes. Love. And then there was a period when there was the civil war in Lebanon, 17 years of unrest, and the Palestinian/Israeli issue, so Marcel addressed all these issues in his vocal compositions, and he created this duality with the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwiche, and you know, this was fantastic work. Nobody can ignore that. Then the civil war finished in 1990, and the Palestinian issue after the first intifadah, we started to see glimpses of hope, but then it died. So that period, this is when Marcel couldn’t keep composing nationalistic songs, unless there was an occasion for it. The civil war was there. There was the Lebanese nationalism. That was a good reason to come up with this kind of repertoire. But when it’s not there, there is no reason to continue this. This is when I noticed he started to compose more instrumental music using a Western orchestra and harmony. He got away from the Arabic musical concept and repertoire. So this Jadal, the duo oud playing together with oud and percussion, was another attempt.

Here’s a compilation of oud players that Ray Rachid of Rachid Music in Brooklyn recommended. Maybe you can tell me something about some of these players.

O.K., Munir Bashir we discussed. Mohamed El Kassagbi, he was one of the first to compose for Oum Kalsoum, and he was a great old player. If you listen to the early recordings from the late ‘20s and the ‘30s, his oud playing is there. It’s the most obvious. Like her voice is 100 and his oud playing is 90, and the rest is 60, 50, 40. You know what I mean? So listen to this. His oud playing is fabulous, especially in this duality he created with Oum Kalsoum, as a composer and oud player who accompanied her in every single performance. And he was one of those who, later in the ‘40s and '50s, was responsible for adding the high string to widen the range of his oud, but he wasn’t captivated by it. This is the difference between him and today’s players, like Shamma and Anouar Brahem. He too has the F string on the top. I tell all these players that sooner not later they should find a solution for this. You can’t let this captivate you.

Ah! Saïd Chraïbi is a really fantastic oud player. He’s Moroccan. His improvisations are so intricate. He knows the tradition very well. You can feel it right away. This is a fantastic musician. Though, lately, he is trying to play more the Turkish style on the oud. I don’t know what’s happening there. But Saïd Chraïbi, definitely an ace in the hole.

So to sum up the whole thing, of the last 20 years of oud players, the good thing is that there is a reemergence of the oud as a solo instrument, which is great, and all these players—Mohamed Zinelabadine (of Tunisia), Bashir, Shamma, Chraïbi—it’s interesting that they care to introduce the oud not only as an accompaniment instrument but also as a solo instrument, so this is a great thing. But of course, there is a great deal from what I hear—it’s all experimental mostly, because there is no clear vision of where we want to drive this instrument. I think it’s healthy. But the one thing I will say is the at the oud is an Arabic instrument. It has to stay an Arabic instrument. So to play on the oud emulating guitar or sitar or these things—this is not the purpose. To play on the oud and play chords and harmonies and imitating flamenco guitar—this is not the purpose. So all these musicians they are better off with their technical abilities, with their musicianship, going back to the roots of the instrument and move with it to whatever vision we have. Because the oud has so many abilities and the maqam system has so much. It’s huge. It’s a fantastic repertoire, and it’s not even developed yet. So we have so much to develop and utilize. It’s infinite.

Related Audio Programs