In honor of Sona Jobarteh playing at Symphony Space on March 20, 2022, we're re-upping Banning's 2019 interview with the Gambian trailblazer. Get to know Sona below and nab those tickets!

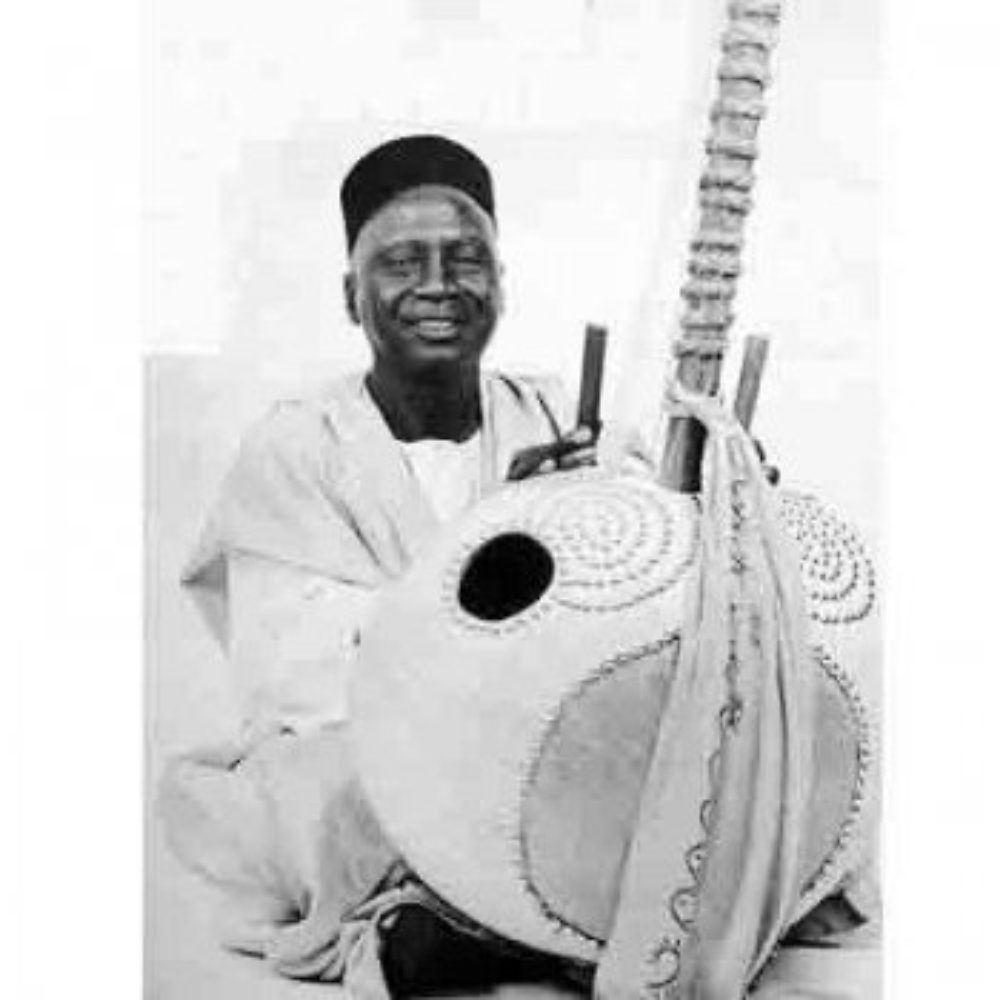

Sona Jobarteh stands out among West African kora maestros. She comes from a line of legendary griot kora players in Gambia, but she also studied Western classical music in the U.K., and played cello before choosing her own path in neo-traditional music. Jobarteh is also a social activist with strong ideas about how to shape the next generation of Africans, and she walks the walk, having established the innovative Gambia Academy of Music and Culture in her native home.

On stage with her five-piece ensemble, Jobarteh positively rips on kora, feeding off the energy of her excellent accompanists in thrilling, even fierce, improvisational exchanges. Her arrangements of traditional Mande songs are razor sharp and highly inventive. She sings in her own manner, not in the traditional style of a griot—just one element that places her sound in a realm of its own.

Afropop’s Banning Eyre saw Jobarteh and her group for the first time at New York’s Symphony Space this summer. (The photos in this feature are his from that performance.) Suffice it to say, he was blown away. He sat down with Jobarteh recently for a talk in New Haven, CT, where she was laying down tracks for an upcoming album release. Here’s their conversation.

Banning Eyre: Tell me how you’re connected with the famous Jobarteh family, which we know from so many great kora players and kora recordings.

Sona Jobarteh: My connection is through my father's line. It's a tradition where you inherit through your father, and the kora in the tradition of being a griot has been in the family for many, many generations. My father is Sanjally Jobarteh, and my grandfather is Amadou Bansang Jobarteh.

Royalty.

Yes, exactly.

Tell me about your early days of absorbing this tradition.

I was very fortunate because I grew up at a time when my older brother, Tunde Jegede, was already studying the kora with my father. He was a student of my dad’s at the time when I was born. He's a lot older than me. Tunde is actually from Nigeria, but he came and studied the kora with my father from quite a young age.

As I say, I was born quite long after he began studying, so by that time, he was already doing pretty well on the instrument, and he's the first one who started to teach me when I was very young.

In Gambia?

In Gambia and in London. In the Gambia, I can't say that I was lucky enough to study with my grandfather. I always wish I had been older. But he passed away when I was 9 or 10 years old, so I was not old enough, so I was not able to study with him in person, although I did play with him. But obviously I was just a beginner. I often wish I could travel back in time as the player that I am now be able to have just one lesson with him. But saying that, I was very lucky to have my father, because my father was Amadou Bansang’s main student in terms of learning kora.

All his sons who studied music were greatly influenced by him, but my father was the one who really studied with him for the most time and toured with him and was always with him. He learned so much from his father, and I was really lucky to be able to study with my father and to get so much knowledge from him, and inspiration from my grandfather through him.

I know little about Tunde’s unusual career in the U.K. How did he learn?

He grew up in the U.K., but he traveled to Gambia when he started to study at the age of 12, I believe.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in the U.K. also, but I spent my childhood between the Gambia and the U.K. Around the age of 14, I got really stuck into studying classical music. So that was a time in my life when I didn't actually get to go back to the Gambia for a long period.

What did you study?

My instrument was the cello. And then for three years I was also majoring in composition. That was a great, really brilliant couple of years.

That's an interesting combination of experiences to be having roughly in the same period of your life. Such different systems of music. Speaking as a musician, how did you find they spoke to each other?

They didn't much. To be very honest with you, they really didn't. When I was at the classical school—I was at the Purcell school, and then at the Royal College of Music pretty much at the same time--it was very explicit that your dedication to this if you want to pursue it has to be absolute. It was very much discouraged for me to show any interest in diversity. Hugely. Explicitly. Not subtly, explicitly. I was told clearly that if I want to pursue this, I must leave other things behind. So it was a difficult time for me, because I couldn't embrace what I connected with fully.

But this is why I chose to major in composition for the last two years, because it was the only place in the classical institution where I could actually bring the tradition I knew from the beginning and not be penalized for it, because it was in a creative context.

Of course. Composition can be applied more broadly. But it sounds like you always knew you wanted to be a musician. How old were you when you started studying kora with your brother?

I was 3 or 4. I didn't make any cognitive decision about that.

And how did your father feel about your studies, coming from a more traditional point of view.

It's interesting with my dad, because I actually started studying with him at the point when I had made my conscious decision that I had been through so much… I had been through classical; I had been through my early training in the tradition; but I had also been through other musical genres. I was touring with Tunde when I was about 13 or 14 as part of his ensemble, which was different again. He was working with musicians from reggae and Indian music, all over the world. So I was having this other experience, absorbing these other kinds of music through my early teenage years. But when I came to it, I knew. Age 17 is when I really decided that the kora is the only instrument, despite everything, that I feel 100 percent connected to. I love all the other instruments, but they do not talk to me the same way. So that's when I really wanted to study the old songs. I wanted to know the old repertoire, because that's the style that I resonate most with, is the old style of playing.

So I went to my father. He was living in Norway at the time. And I asked him, "Will you teach me?" And I think it was interesting, because he agreed, and we spent such intensive time just on the side of his bed for so long. In Norway. Imagine. Studying and studying and studying as much as I could. I never knew until many years later how he internalized that whole process. It was when I had an interview about five or six years ago. It was the first time I had ever done an interview with my dad in that way, and the interviewer asked him, "What did you think about your daughter?"

And he said, "Yeah, if she wants to do this. I told her, ‘Make sure you don't consider the female thing. I'm going to teach you as my child, not as my daughter. So I'm seeing you as my child, not as my daughter. This is me passing it on to the next generation. I'm not seeing you as a woman or a man or anything, just my child.’” And it's true. He told me at the time, "The one thing I want is to make sure you become a good kora player, not a female kora player, a good kora player."

Well, he certainly did that. You're a wonderful kora player.

Well, what was interesting is the interviewer asked him if he thought I had succeeded. And you know, my dad is the older generation. They don't say, "Oh, well done," and things like that. So, after a pause, he said, "Yes. She did." And that meant the world to me. Because I never heard him say what he actually thought, and if I did justice to what he believed he had taught me. So that meant a lot.

Great story. It is interesting that you are focused on the old repertoire. When I heard you play live, which was the first time I'd really focused on what you do, I recognized a lot of the songs from my knowledge of Mande music. You are working with a lot of the classic repertoire, but the arrangements are so interesting and original. And your ensemble is fantastic, such a complex but clean sound. You hear just every note and the space and it is fantastic. No clutter at all, even though people are playing some crazy stuff. Do you feel like your experience with composing gave you an approach to putting the ensemble together this way?

Yes. One hundred percent. Definitely. Because putting the group and the ensemble together was a totally different ambition from creating the album. My album, Fasiya, doesn't feature the band at all. So the composition of that is different. And then creating the stage show was a new frontier. After releasing the album, I thought I had to create the stage show. How do I do that? And in my mind, I knew exactly what I wanted. I knew exactly what kind of musicians I wanted. But how do you find them? How do you get the right energy in the right synching together? How do we bond on and off the stage? All these kinds of elements were revealed to me. And I went through so many musicians over the course of four or five years. So many musicians!

Interesting. But the group is stable now?

Yes. This final group has been together for years now.

Your guitar player is amazing. Tell me about him.

His name is Derek Johnson. His story is very interesting, because I met him… Well he met me when I was a child. I can't say I met him since I was only a child. He remembers me on the floor with a car or whatever. He's from Jamaica originally, but raised in the U.K. also. He is very much into reggae. That's his background. And he's toured with some of the biggest reggae artists. He's one of the musicians whose been there and done that on pretty much everything when it comes to touring. Again, I would say I feel a huge honor to have the musicians I have in this group. I wasn’t sure I could get the commitment, the hundred percent commitment from the group that I finally selected, because they were already in such high demand, and they were already on the top of their game. So I am just so thankful that every single one of them has committed and believes in it, and has decided to put this project first.

It looks like you're having a great time up there also.

Yes, yes, we make it look like that.

I know what that is. You do a good job. Your percussionist on djembe and calabash is also an incredible stage performer.

Yes. Mamadou Sarr.

You two have these wonderful one-on-one interactions during the show. Quite gripping to watch.

He was the easiest person I think for me in terms of that, because from the first time I played with him, he played three or four seconds and I was like, "Yes. I don't care what you do. Yes. Yes.” He's Senegalese. He plays with Baaba Maal, so he's very well-established. What I really needed from a percussionist is someone who understands the Manding tradition, and at the same time can also bring innovation to it—someone who is not so stuck that I can't give them something new and not make him struggle. This was always my challenge before I found him. I either got very traditional players who knew the songs, and it was beautiful to play as long as we stuck to “Jarabi” as “Jarabi” is played. But as soon as you want to change the timing or put it on its head or push it out and do different things, it becomes a big problem. And likewise if you go for someone who can do that innovation, then they don't know the tradition. I was always falling in between those two places, so to find Mamadou, who could do both, was a blessing.

Here’s something that strikes me. You take a song like “Jarabi,” which has been done in so many versions by so many West African artists. I mean, Toumani seems to include it on every album in some new manifestation. I see a connection between this tradition and classic jazz, because it's always a matter reinventing the same songs, the standards. Even though it's a song that’s been played one million times, there's an aesthetic that you are going to play that song and honor its essence, but you're going to add yourself into it and make it your own. A lot of kinds of music are not like that. When I studied with Djelimady Tounkara in Bamako, he always made this point, saying that Mande music was the basis of jazz.

That could be proved in many ways. I think music tells the story without much else, because you can hear it. You see the amount of people who have come into this tradition, who don't know anything about it, and they get so excited. I actually notice that more in America than the rest of the world. I think in Europe, they are quite familiar with West African music. They have been following it, and they know it. In America, it’s very interesting for me because it's different. There are a lot of people in the audience who don't know this music, and that's new for me, to have audiences that are being educated by hearing the music for the first time. It is interesting to hear their responses. So many times, they will be talking about Jimi Hendrix, jazz this, Dizzy Gillespie that. And I'm like, "Wow, really?" And they cannot be wrong. They’re hearing something they can relate to, which is very important.

This is a subject we have explored a lot on our radio program. Why is it that West African music, certain kinds of it in particular, really resonate with American audiences? People don't have to know the music, or know why they like it. They just feel it. I think it has a lot to do with history, because people from that part of Africa were really the bedrock of so much American music. Even though so much has changed as all these centuries have gone by, you can still feel a connection. I think of it as twins separated at birth. When they come together, whether it's the bluesy sounds of the Sahara, or the ngoni’s connection to the banjo, people get it instinctively. I'm very interested in those narratives.

They are interesting. And I think you're right. For me, it's history. It's chronology. You can't be surprised if people are taken from one place to another they take their culture and traditions with them. So whatever is born at the place they arrive will also have those influences embedded in it. It's natural.

A beautiful outcome of a tragic history.

Right. It's amazing. I'm also interested in exploring more of those connections, seeing the two ends of the story coming back together again.

Let's talk about your recordings. You released Fasiya in 2011. And now you're working on a new album. What was your concept back then? And what are you trying to do now?

I see Fasiya as my statement. I had been through so much, so many different avenues and paths and different possibilities to pursue. But this album was the album that actually resulted because I made the decision, consciously, to follow what is natural for me, and not to worry what the outcome is. I was very concerned, prior to releasing this, about conforming, about not going into music that the majority of people around me don't understand, singing in a language that nobody can understand. These are all things that were weighing heavily on me, and I was always looking for a music that I could do that people would understand and I would get recognition for.

We were talking about Derek Johnson, the guitarist. He was very instrumental in that. I gave him a credit on the album, because I remember, I went to visit him for something, and he told me, as he was cooking, "I don't know why you're searching all over the place. The thing that you are looking for is right under your nose." He was just saying it offhandedly, but he didn't know how much that penetrated. For months, that kept ringing around and around in my head. And I realized, he's right. Stop looking. Just do the thing that you love. Sit down and write the music you want to write, and then whatever happens, so be it. And that's what Fasiya was about. It was just me finally being able to be myself and not worry or care whether people like it or not.

What does fasiya mean?

Fasiya has a very complex meaning, actually. I will try to make it short. It's basically heritage, but that is a huge understatement and glosses over what it really means. It's paternal heritage, from your father's side. But there's a lot of cultural significance in the word that is lost even today in Mande society, where the word gets used to mean just inheritance. It really means a lot more than that. It is talking about what is your duty or your role, generation to generation, as somebody born into the griot tradition. What is your duty to the mother's life? Your father's side? And the fact that there's also the tension between one generation and the next, what the earlier generation has done. How can you honor that but also surpass it without dishonoring it. It's a balance. It's about the balance between the modern in the old, about the mother’s and the father’s line, and making sure tradition is preserved but also brought into a new meaning.

So you're reworking traditional songs on Fasiya, but turning them into new compositions. Maybe you could talk about a couple of them in terms of the messages you wanted to convey.

You mentioned that I use a lot of traditional songs. You can recognize some of the roots of the songs, and yes, I draw on them. I chose to keep the first song “Jarabi,” as it was. I kept its original meaning, because there's no point. “Jarabi” is well known. and this was partly in honor of Toumani [Diabate], because he inspired my generation. He was the one who went before, and this was one of the first songs that I decided to really study hard from his CD.

He's recorded so many versions of that song.

He has, but I'm talking about the solo version from his first album, Kaira. That was my tutorial, that album. So this was almost a homage to him and what he did, and how much he influenced me and so many others of my generation. But then the vocals. The vocals here are very different from the institution. It's almost like a split personality. Now I'm seeing them becoming one, but at the point when I did Fasiya, they were very much two different people. I had been my whole life an instrumentalist, so singing was very new. I was not planning to sing or be a singer at all. This album I wrote was supposed to have a singer doing it for me. But again, you get these little gems in your life. And this one was called Juldeh Camara, a riti player from Gambia.

Yes. We know him. Wonderful artist.

He is a Fula musician. And he told me, "Why are you looking for a singer? Sing it yourself." And I was, no. But then I started trying to sing, and here I am. I still find it difficult to say I'm a singer, because I don't see myself that way. I sing, but I'm a musician and a composer and arranger.

But you sing beautifully. And you play very nice guitar as well. When did that come?

That came much later. I just picked it up. I never studied it. So I don't say I’m a guitarist, because I don't play anything except my music. So don't hire me. I just know what I need to know to get the sound I want. I leave that to the Dereks of this world. For the guitar, it's very personal. It's very much a personal instrument. I use it for my own music, but I love its ability to adapt to different tones and sounds to the kora, and to different genres. It has such flexibility and range. It's amazing to work with it. And I write with it most of the time. But I came to the guitar much, much later.

You talked about singing. What about lyrics? You've written a lot of lyrics here.

Yes, so the lyrics on this album, again, I'm in a very different place now from when I wrote this album. I was still not very sure about where I wanted to go. All I knew was I wanted to do something different. But I was not seeing the concrete answer of how I wanted to be different. So this is my first step. Lyrically, I didn't want to sing jeliya, like a griot. I did not want to sing the stuff that has been sung a million times. It also wasn't my vocal style. It's so amazing and hugely important to study that, but I could not perform it. So I wanted to bring composition to the vocal side. So this is where I was trying to do something new. I was inspired by someone like Habib Koite. He brought composition to his vocal style. It wasn't just praise singing. It wasn't praise singing at all, and it wasn't reacting to the environment at that moment, but it was actually something constructed in a very different way. I wanted to do something more like that.

Habib is a true original. That makes a lot of sense. I think of him as someone who was raised in tradition but he doesn't play tradition. He draws on many traditions. But he's not making a mishmash of world music. It's a very well constructed dialogue among Malian traditions.

Yes. Very clear. It's very clear.

I think he's inspired a lot of people to think out of the box.

He has. I see myself as a student of all these people. Thank God for the world of CDs, because that was my learning experience. Listening to them, analyzing them. You mentioned guitar. The person who taught me guitar was Djelimady.

Really? Is that right? Tell me about that.

Via CD. I had about four or five seconds of his CD Sigui, that I just kept looping and looping. He's the one who inspired me to play. I listened to that CD like a mad person for like a year of my life. In my teenage years, I was just hugging that so close. I learned a number of songs from that album, and that inspired me. I also listened to In Griot Time, with Djelimady on the cover. I think that’s where I saw your name.

Right. That was the CD that went with my first book. How nice to hear! Let's jump to the present and talk about the new album, and what you're trying to do now. Is it with the group I saw on stage?

No. Separate project.

So you have never really recorded with this group.

No. We haven't.

You have to do a live album.

We will do it, but it has to be a different project. I would love to have the visuals to back that up, rather than just an album. But this album is very different because it comes with a huge expectation from me to live up to my present situation and what it is that I'm working on right now. It's a little bit complicated because, for me, my ambitions and my dreams and my focus on music and being a musician on stage is not worthwhile unless I am delivering the message that I'm putting out there, and I'm also delivering them on the ground. This is a very important part of my life. So it has long been my ambition to set up an institution in West Africa that would bring together history and cultural education and music.

Now, as I'm actually doing that, the impact is important to me. So the new album is an oral representation of what I'm actually working on physically at the Academy. That's how I see it. And not only is it an oral representation, but it's also the messenger to be able to transfer culture, language, and history, by being able to communicate this message to other people from all around the world, and raise awareness to entice people and inspire people to actually motivate them in the areas where I am challenging them. This is very much an album that is challenging.

This goes back to something I was trying to communicate in my song “Fasiya,” which is based on “Tiramakan.” The song is talking about heritage, but for me at that time, I was very much concerned that the true role of a griot is not just to verify the status quo, but to challenge it. At the time of Tiramakan, and his relationship to the King, Sunjata, the song, the spoken word, the music, these were real. Sunjata would not go to the field without his griot to inspire him to conquer, inspire him to go out there and do whatever it was.

Without the music, Sunjata would not have received the message of the people, who may not always agree with what he did. The griot has exclusive right to be that mediator between the people and the ruler. It was not about praise singing only. That was one aspect of it at the right time. But criticizing, and being the voice of people, and the voice of reason also, and taking a step away from politics, away from daily affairs just to question things very clearly. I think this is a very key role of the griot that is being left behind because of the complications of money. I have to be very honest. The tradition can be jeopardized sometime when it only relies on money.

Colonial history has a lot to do with that as well.

Yes. That's another side of it. This is an area where I want to breathe life into it. I feel like the next generation is turning away to some degree. And I think the voices we really need are the ones that are turning away from tradition because they feel like it's not challenging them. It doesn't give them a voice, so they go to foreign music to find their voice. So my idea is say, “No, that challenge and that voice are right here.”

Fascinating. This reminds me of some young griot rappers I met in Bamako who talked about rap as reviving an important part of the griot tradition, the part that criticizes and speaks truth to power. Talk about some of the messages on this new album.

One is education. You mentioned the colonial history. This is something that I am campaigning for in a huge way, challenging the fact that we still have not actually recognized the stagnant situation with education across the entire continent. It's not just Manding or Gambia. This is across the entire continent. It is not been recognized, and you cannot make changes until you recognize the problem.

We have a version of that problem here too.

Right. But in different ways. I feel like we can't talk about the challenges of entrepreneurship in Africa, migration and Africa, dealing with leaders in Africa, unless we really get to the core of what is going wrong with the education system. At the moment there's so much hype and push behind, build more schools, build more schools, and no question about what those schools are doing. In the Gambia for one, I could tell you that every single situation that we complain about, the challenges that we face for this or that reason, there are elements of it that are born in the education system in the country. And the impact is so huge that I cannot believe that still now, we are still not recognizing it and reforming it.

So this is the reason why we set up the Academy and why I'm running the Academy, to actually template and prove what happens when you do actually perform the education system, and when you do give young people a chance to be educated in different ways. How does that affect their mentality? How does that affect their sense of who they are, and the world they live in, and their approach to whatever their profession is in life. So it's a very different approach and a different mentality, and I see the results already after just a few years. Students study at the school and their mentality changes. Hugely. That's very underrated at the moment. Again, I'm doing it. I'm not just singing about and talking about it. You can actually come and see it and see the curriculum, and I want the curriculum to be taken outside. Anything I'm doing, I want to be scalable. I want it to be a template. Not something where you come to my school and this is the only place you can get this education. No. This is a system that I'm developing to become transplanted to other schools.

That is fascinating. I would love to visit and see that some time. This is one of the things we're looking at with Afropop. We have 30 years of field work in Africa that is all about music and culture and history, and a lot of it connects with American history. Americans have a very simplistic impression of their relationship with Africa. That's one of our problems with incomplete education. But we are really looking at ways to take that Afropop archive and turn it into educational tools, with a somewhat similar idea, to create a multi-disciplinary curriculum that can be shared. So I'm really glad to hear about your academy. I wish you great luck with it. And I look forward to hearing the album. What's the timeline looking like?

Well, the timeline was about two years ago. It's still a work in progress. If they would stop booking shows for me, I might actually be able to get some things done. But were looking at the end of this year or early next year. I think the release date will be within the first quarter of next year.

Well, we will be waiting for it. Thanks so much for speaking with me.

My pleasure.