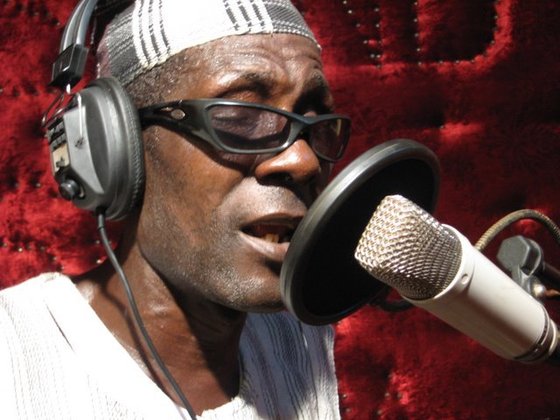

Afropop Worldwide producer Sam Backer got a chance to interview the blind Sierra Leonean musician Sorie Kondi during a New York stop of his current US tour. The tour, enabled by a successful kickstarter campaign, marks Sorie's first time in the United States. Given his immense musical talent and obvious creative abilities, we sincerely hope that he will come again soon. The interview was held at the apartment of the DJ Boima Tucker, and was conducted with the help of a translator.

Sorie Kondi: Good Morning

Sam Backer: Welcome! I'm excited that you finally made it!

Sorie: I too am very happy.

Sam: You were supposed to come earlier right? For the South by Southwest music festival?

Sorie: Yes. I was supposed to come, but because of financial problems I couldn’t make it.

Sam: Let’s just start by talking about your instrument, the kondi. [The kondi is a type of thumb piano from Sierra Leone]. How did you first come to play it?

Sorie: I started playing as a child. Someone started to teach me how to play it, but they did not do it too much extent. But I continued to play after.

Sam: Was it a popular instrument where you grew up? Were there lots of kondi players?

Sorie: Yeah- they used to be there before in the village. So many people playing the kondi- but they are all dead now.

Sam: So you heard a lot of kondi music?

Sorie: No. I never heard too much of kondi music.

Sam: So they all passed away before you started playing and listening to it?

Sorie: Yes. They all died before I started playing it.

Sam: You also made some changes to the kondi, correct? Could you explain them?

Sorie: Yes. I did a lot of things to it. In those days, they never used amps in the kondi to connect it to a loud speakers or big speakers. But I did something to the kondi so that you can even connect the amp, that will give to it a big sound like speakers. So you can use it like a band, you can make it play louder, more than it used to play before. I did some kind of connections in it.

Sam: How did you figure out how to do that?

Sorie: I just sat down, and I had a microphone to do like shoes. I heard the electric sound of guitars going through the speaker, so I thought one day, let me see if I can do something on this thing. So I started, and I spoiled the whole kondi, trying to do some kind of wiring on it. It was just a gift from god. I didn't expect it to sound this way. I can’t really explain how.

Sam: Did you make that change in Freetown or before?

Sorie: I did it in Freetown.

Sam: Did you have to get louder to cut through the sounds of the market?

Sorie: Yes.

Sam: How did you start performing?

Sorie: I started from my village and then came to the city. I believe that in the city people are accepting more. Then I started performing on the street. People started gathering around as I performed, some people would donate money to me, give money to me. That’s the way I started it. I started performing on the street.

Sam: On your website, it says that you used to play ceremonies? Can you tell me about that?

Sorie: Yes they normally invite me to marriages, ceremonies- like when they have big festivals in the cities, cultural festivals. They invite me to those big big hotels that white people go in Sierra Leone, to entertain the crowd.

Sam: Let’s talk about your songs. When did you first start to write your own songs?

Sorie: I started composing music in the year 1977. That is the time I think I realized that I started composing something good, that have sense on it, and that has a strong meaning. I started that in 1977.

Sam: So you always wrote your own songs, but it took a while to for you to create something that you felt was really good?

Sorie: I compose my song through imagination because I am not educated. I cannot write them in a paper or have a draft of them. It just comes into my head, it’s just like imagination, I just did some imagination to start composing, but I never wrote any of my songs.

Sam: Your songs have definite parts. Are they written all the way through or is there some improvisation?

Sorie: I don't write them. I never write nothing. Each of my songs has different styles in them. and I have different ways that I normally do my songs. Like this song has its own style, and this song has its own particular style, and I just mix them together with different styles.

Sam: I can only understand little pieces of your lyrics, but from what I can understand they seem really powerful, really important to the music. How do you write your lyrics?

Sorie: It’s all about a sense of hearing. I never wrote my songs- I just play them by ear.

Sam. How do you come up with your lyrics, I guess I'm trying to say.

Sorie: My lyrics normally come from hearing what people are saying and what is going around the community, things that are happening. I cannot see but I normally hear what people are saying. So I started singing on them. This is what is going on and it’s not good, this is what is going on and its not good. Something like that. That’s the way I came up with these lyrics. Things that are happening, I started imagining them and then I said okay let me do something with them. Like singing something on them.

Sam: So are they always based on things that are happening around you?

Sorie: Sometimes my songs are about things that are not happening but I know, at the end it will happen.

Sam: I first heard your music from the song, "Without Money, No Family." could you talk about that song?

Sorie: The song No Money No Family is like this: Right now, I am in the States. I would never have come here if I had money. But I am here just to strike, to survive, to feed my family to take care of my wife and my one girl child. So it’s like in Sierra Leone where I come from, if you don’t have money people don’t know you. If you don’t have money your family will never respect you. Because I am blind, and normally I would go across the street begging, people don’t care about me. People don’t want to know me, they don't want to know even if I am existing in the world. That's why I say, if you don’t have money, you will never have family closer to you. That is what is existing in our own country, or in other places in African countries- I don't know if it exists in the U.S. Even the family you came from, they will never respect you. So that’s why I say, if you don’t have money people, will never respect you.

If I come to you to beg, you don’t have to give me anything but don’t disrespect me. Because I'm blind and have no money, people don’t want to know about my health, people don’t want to help take care of me. Whatever I do, I struggle hard to feed my family by walking across the street, begging people- no one cares, not even the government doesn't take care of me- I take care of myself.

Sam: What about “Don’t Molest me?”

Sorie: The song is similar to no money no family. If I come to you to beg you, if you don’t have to give me, don’t disrespect me. If you don't have anything to give, don't say "Get out of my house! I don't want to see you!". That's normally the kind of aggressive way of talking to people. That's why I'm saying to people- if you don't have to give me when I beg you, please don't disrespect me, don’t molest me. I know if you don’t have to give me, God will give to me.

It's the way I exist- I normally begged people through my music. Sometimes when I go to other places, singing my music, people would start shouting at me, "Just get out of this place. We don't want to see you here. Always you are around to beg." So that's what I'm singing about.

Sam: Have things changed since your music has gotten better known?

Sorie: Through these two songs I did, like “Don’t molest me,” as soon as that song came out, some people started to change. They started feeling sorrowful for me, like “This guy is not seeing but he knows we are not treating him well.” Some people that normally disrespected me said, "this song is nice, it has meaning to his life." Some people started changing but some people still don’t change. What makes more people change is people starting to buy my song, and liking it. But some people accept it, and some people still don't accept the change.

Sam: How widely is your music known in Sierra Leone?

Sorie: My music in Sierra Leone is nearly 200% known. Everybody in Sierra Leone knows Sorie Kundi, everybody in the whole Sierra Leone, even the smallest village, even the little kids. They know. Most of the time, when I am struggling to cross the street, or go to a place that is not to good for me, the kids control me. "Okay Sorie Kondi come this way, let me help you. Afterwards you play a song for me so I can dance.” That’s what normally the kids, do they normally chase me, like "hey look at Sorie Kondi, lets go!" Everybody in the country know my music. But still, there is no kind of help, from anyone. People like listening to my music, they like dancing to my music, but they don’t come out to help me. Like how I am living, how I am doing things, how I am taking care of my child, sending her to school- I am paying her school fees through the performance that I do on the street. I feed my house with the performances I do on the street- I am still living in a small room, with my wife and my daughter.

Sam: When did you get well known?

Sorie: They started knowing me in Sierra Leone since the year 1980 until now.

Sam: So they know you well?

Sorie: Yes. They've been knowing me for a very long time.

Sam: I know you tried to record a first album and then the war intruded. Can you talk about that?

Sorie: [Laughs] My first music was during the rebel days, and everything was broke up by that. My manager was a Ghanian and he ran away, and don’t know where he is up to now. So everyone run away, I decided to stay. If i’m going to die let me die, if I am going to live let me live. No one was there to help me run away. I just stayed indoors. I didn’t know if a stray bullet or a bomb was coming, just like that. I stayed. I wanted to do my first song but the rebels broke everything.

Sam: Your recordings first got to the West through Luke Wasserman. How did you meet and start working together?

Sorie: It sounds so funny when you ask that question. One day I was playing on the street. Traveling all the way from the city to a town called Lungi, it is on the upper local district. You can use the ferry to cross to the Lungi. Luke, he stayed in Lungi. So one day, I crossed the ferry and I started playing on the streets. Then some kids were like “Uncle can you play for us?” “Then I said, “No I can’t play because I am so tired. I walked all the way from Freetown to be in Lungi. I’m hungry. I want to eat.”

Then they said, “Okay we can offer you something to eat,” but they didn't offer me anything. They just had little amount of money, they offered me some coins, some small small coins. “Uncle can you please play for us? This is all we have." I don't accept the money, I just say hold it.

Then the kids said , “Uncle, we want take you to someone who likes this music that you are doing.”

I said, “Who is that person?” I was still annoyed with the kids, I didn’t trust what they were saying. I think that some of the kids had seen Luke doing some video or cultural documentary on this music. So I said, "Take me now to this man you are talking about.

So the kids take me to Luke Wasserman, and Luke told the kids- "you have taken this man to me, can he play for me so I can see?" I played for Luke, and then Luke asked me where I was staying. I said that I don't stay anywhere in this place, it's like, I just traveled all the way from Freetown to here, and I have no place to stay. I am now looking for a place to stay in fact.

Then Luke told me, “Let me take you to some of the Chiefs that are around this community.” So Luke took me to some of the chiefs around the community, and he gave to the chiefs small amounts of money for them to lodge me. After that, after they lodged me, at about ten in the night, Luke came back to the house and said over “I want to do a local recording with you.” Then I recorded the music, and that’s the way I came in touch with Luke.

Sam: What about the second record, “Without Money No Family?”

Sorie: After I did the recording with Luke, Luke took some of the music to one of his friends, Ishmael. He asked Ishmael to listen to some of the recording, and he said “Ishmael, can you listen to this old man music?” and Ishmael said “It’s good! Let’s do something for this man. I want to do something for this man. He has talent.”

So Luke and Ishmael came to me in Freetown just after we had done all these recordings and conversations. They asked me if I wanted to do music for me. At first, I said no. Just putting out a single like that is no good. I told them if they helped me make an album then I would do it. They both came together and we did an album.

Sam: That’s the Without Money, No Family album?

Sorie: Yes.

Sam: What was it like working with a full studio for this album? Because I know there is a big difference between the first recording, where it is just you, and the second, where there are overdubs.

Sorie: It was live recording in the studio, all of the instruments were live. There was no computer business. It was so strange to me- when Luke set up the studio- even luke got confused how to set up the recording for me! I played all the instruments. I played the kondi, and then after the k0ndi, I played the drums, and after playing the drums, I played what we called the shebure, after the shebure, I played the triangle, which has a different sound. I played all the instruments- when I played, Luke would record it on the computer.

Sam: You have a new album right?

Sorie: Yea, it’s called Thogolobea

Sam: When did you record that?

Sorie: 2011

Sam: Is it released yet?

Sorie: Yea, yea it is released in Sierra Leone but it has no good promotion, for it to be in the States or other places. I don't have anyone to promote for me like that.

Sam: I heard one track. It seems to sound more electronic, is that right?

Sorie: It is both electronic and traditional way. I play the Kundi, and then I play some of the instruments form the studio, and mix them together.

Sam: So your trying to bridge the gap between traditional and electronic?

Sorie: Yes. If I get the opportunity then I can do more then that. I am trying to do that.

Sam: Which kind of brings us to this current tour. How did you and Boima start working together?

Sorie: I knew Boima through Luke. I had never met Boima until I reached the United States. They way Boima takes care of me, I know he is a good soul.

Sam: What’s your relationship to current Sierra Leonean music. How does your music compared to theirs?

Sorie: There is a lot of difference. They use a lot of electronics. Whereas, I use manual things, a physical kondi. [Laughs]. Let me ask you, Have you ever seen a kondi in the US, someone playing it?

Sam: No.

Sorie: Well, my whole music I play is different from those other artists. But we have good colleague relationships. I do live music, and the other musicians are doing computer work.

Sam: If there is a Sierra Leonean music fan, they would listen to electronic music, and then Sorie Kondi, and then electronic music?

Sorie: People appreciate my music. They invite me to big festivals and to the clubs to preform. I only know about myself. I am not seeing, but I know that people appreciate my music because people normally invite me to the big occasions of the country.

Sam: What are you plans for after this tour?

Sorie: I am happy to be in the States, I pray for more people to help me so my music can be established more than this. From what I have seen, there is a bigger opportunity in the US than in Sierra Leone. The way people appreciate me when I is performing is different then in Sierra Leone, because here I have some kind of development and improvement in my music. It's like people strongly appreciate me- that’s why they help me to be here. So if I have the chance to go back home, I hope that people in the US will help me to continue to develop the music like this.

Sam: We do too. Thank you so much for talking to us.

Sorie Kondi's studio album Without Money No Family is out now on EarthCD