Two things about Ghanaian gyil music are likely to grab a first-time listener: the deep, resonant buzz of the bass notes, and the polyrhythmic virtuosity—the right-hand/left-hand limb independence of master players.

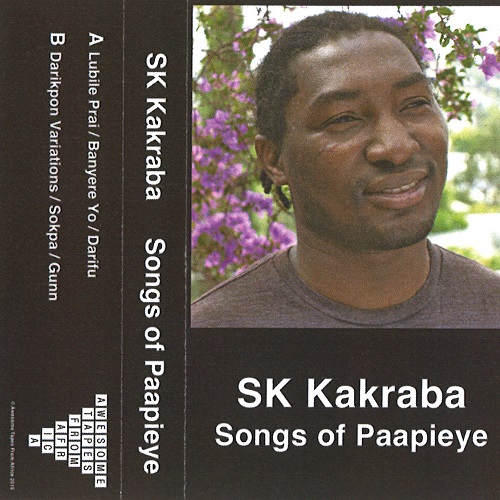

The Awesome Tapes From Africa label is known for its reissues of obscure African popular music, with the original sources often coming from cassettes. This is the label’s first venture into releasing new material. Fans of the label’s bold and wide-ranging aesthetic will probably possess the open ears required to dive into Songs of Paapieye, the new recording from Ghanaian gyil player SK Kakraba.

The gyil is a traditional wooden xylophone, with generally 14 keys and a range that spans almost three octaves. The instrument’s unique buzzing sound is created with a system of calabash gourd resonators placed under the wooden slats; the gourds have holes in them, which are filled with spiders’ egg sacs, or—if plentiful spiders aren’t on hand—some other thin material that accentuates vibrations. (The record takes its title from the name in Kakraba’s Lobi language for calabash.)

The buzzing sound is similar to that found on other African instruments such as the djembe or the mbira, a quality that is sometimes achieved by affixing bottle caps or metal rings to a sounding board or drum shell. Some have compared this buzzing aesthetic in African music to the mists and clouds that often characterize traditional Chinese landscape painting: Figures and scenes aren’t meant to be seen clearly, and the shrouding fog is essential to the mood and atmosphere. But anyone who can appreciate the timbral color of a distorted guitar should be able to relate to what’s happening with the bass notes on a gyil. There are times when the gyil can sound similar to a steel drum, or even to a didgeridu, with its deep and haunting resonance and overtones. Fans of Konono No. 1’s electric likembe jams and John Cage’s prepared piano pieces might find some terrain of sonic overlap with Kakraba’s gyil music. Some others may find the instrument’s timbre to be jarring.

SK Kakraba was the student of his uncle Kakraba Lobi, who was probably the world’s most renowned gyil player. Lobi passed away in 2007. The gyil is something like the national instrument of the Lobi and Dagara people of northern Ghana, Burkina Faso, Cote d’Ivoire and elsewhere. Kakraba has taken his instrument all over the world, from festivals and social settings in his Lobi homeland in the northern part of Ghana, to the streets of its southern coastal capital Accra, to the country’s universities and cultural centers, and as an international performer and educator. Now in his late 30s, Kakraba lives in Los Angeles.

Kakraba performs these pieces solo, unaccompanied and without overdub, though in many cases the music might be played in a traditional setting with another gyil player, with the accompaniment of drums or bells and with singing as well. The solo setting allows a listener to zero in on Kakraba’s polyrhythmic force and creativity.

The opening track, "Lubile Prai," which is inspired by birdsong, serves as a kind of brief warm-up, never establishing a set rhythmic through-line, but popping in and out of steady pulsation. From there the material gets more hefty.

“Banyere Yo” has patches of what could be akin to a drummer’s 16th-note roll or paradiddle exercises. Then, as a new section begins, a bass figure asserts itself and Kakraba’s right hand maps out extensive counter rhythms and melodic lines that seem to curl off of the lower-end phrases. At one point a tick-tocking siren-like two-note pattern emerges in the middle register, with offbeat accent lines and ornaments tumbling around it.

There are fascinating pieces of cultural history, storytelling and morality behind this repertory. Some of these songs are humorous cautionary tales about drinking pito, a homemade millet beer. Others are traditional pieces performed for funeral dances. The balance of the material seems to be associated with either drinking or dying, which suggests a well-rounded sense of life’s ups and downs. Whether a first-time listener will be able to distinguish the funereal music from the good-time party songs is another question.