Contributing producer Saxon Baird recently spent some time in Kingston, Jamaica for his forthcoming radio program on the rise of U.K. reggae in the late 1970s and '80s. Clearly, getting a Jamaican perspective on this time period was of the utmost importance. It was also a good excuse catch up with some reggae heavyweights.

Over the course of his career, the music of reggae star Half Pint (born Lindon Roberts) has kept a straight and narrow path. Despite changing trends, he's kept his lyrics socially conscious and deeply ingrained with hope and optimism. One of the first things you notice about the man upon meeting him is that he is much like his music- thoughtful, full of smiles, and seemingly lacking the ego that comes with so many well-known musical artists. His humility is all that more of a welcome surprise considering his resume. Over the course of his career, Half Pint has scored numerous hit singles in Jamaica, toured the world, and had his songs covered by the likes of Sublime and The Rolling Stones.

On a hot and humid Kingston evening in late February, Half Pint suggested we do the interview outside. Congregating around his pick-up truck, he was kind enough to lend some time to chat about his career, his experience interacting with the British reggae scene in the '80s, the state of the Jamaican music industry and much more.

Saxon Baird: You got started singing for soundsystems, correct?

Half Pint: I started singing on the sound systems in the dancehalls back in '77-'78 through 1983. Then I started recording some of my early songs that I was covering back in the dancehalls in 1978-1979. I recorded them around 1980. Then I did some work with some producers including Prince Jammy for whom I did the "Morning Man Skank" showcase which ran five tracks. It included "Money Man Skank," "Punchie Lou," "Give me some Lovin'" and "If I had a Hammer." Then I did songs like "Sally" which was released in 1982 by a former producer of mine. I also cut "Winsome" around that time which was covered by The Rolling Stones around 1987.

Can you talk a little bit about how you originally hooked up with King Jammy?

He was a student of King Tubby and was also producing some stuff himself- things like Black Uhuru and Wayne Smith and some others artists. I was singing on the soundsystems before I even met him in person even though we both lived in the same community of Kingston 11, Waterhouse. At the time, I guess he was producing artists that he had known before he met me.

Around this time I was coming along in the dancehall, making my own debut. I started recording some songs with him around 1982 and also 1983 because he eventually heard me singing for soundsystems like Mellow Vibes in the dancehalls and yards down in Waterhouse. Jammy didn't have a soundsystem himself as of yet, but he did build amps that would make up the soundsystems and the ones used in the studios as well.

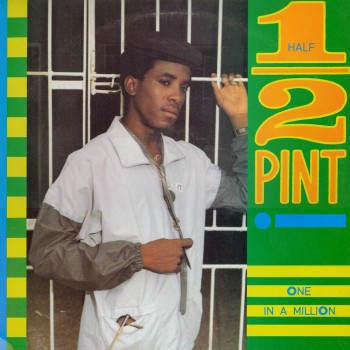

When I eventually recorded songs with him, they were ones that I had already been singing like "Mr. Landlord" and "Money Man Skank." These songs mainly focused on the social lifestyle that I was experiencing and seeing at the time. We eventually did an album together called 'One in a Million' which was released by Greensleeves in England.

Basically, at the time, I knew Jammy was a producer working with other artists so I wanted to do some work with him. And he had heard me in the yards and wanted to do work with me too. So working with him was like one hand washing the other.

When 'One in the Million' was released by Greensleeves it was available only in the UK at first. How did that come about?

I didn't have any management at time. Greensleeves was a new distributing company that had grown out of Jet Star which was also in the UK and had already worked with producers like Jammy and others out of Jamaica. So they already had a relationship with them. Greensleeves was the next independent label in the UK. All the Jamaican producers like "Junjo" Lawes, Jammy and other various producers would have Chris Cracknell release tracks for them over there.

I guess, at the time, Chris had proposed an exclusive UK-release for 'One in a Million' to Jammy and that's how it came about to be released in the UK.

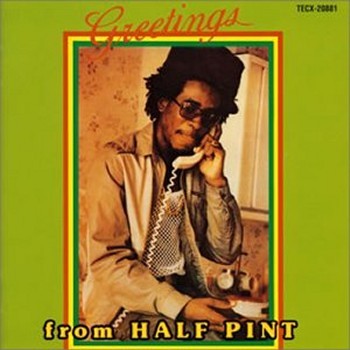

Since we're talking about the UK, I heard a story about how George Phang originally heard you sing something similar to "Greetings" over the Heavenless riddim with a soundsystem in the UK two-years before the actual release of "Greetings." Is that true?

Phang had heard me in the dancehalls and knew I could sing. We would try and write lyrics and catch a melody over over some of the tracks that we would hear over the years in the dancehall while working with the soundsystems. So Phang had heard me before and knew I could sing.

But actually, we were in the UK in 1985 when we cut that track ["Greetings"]- we had gone to see Mr. Palmer of Jet Star. But in 1984 while George Phang and I were in Jamaica, I had done a track with him which was between me, Barrington Levy and I think Junior Delgado or Michael Palmer. So the "Greetings" single actually started out as a combination track but Phang and I didn't have enough follow-up work at the time so the single wasn't released. But in 1985, we went to London and ended up doing "Greetings" there.

One morning, we got up and went to the studio down by Stockwell called TMC. I even remember the named of the engineer was Andy. So we put on the 24-track tape and the first track was titled "Greetings (Heavenless Riddim)" So they put it on and I cut the vocals in a single take.

In all, I did three tracks that day: "The Living in Hard," "You Say You Couldn't Come" and "Greetings." I did them all straight in one morning. When cutting "Greetings" in London, though, I felt I was able to really express myself when seeing the economic state of entire world at the time. Particularly when the economic situation in London was similar to what it was in Jamaica at the time. So "Greetings" was like me saying "blessed are the poor because they shall inherit the Earth and they shall know God." I was trying to express that in my own terms in saying "greetings to all the ragamuffins from Jah, the most high, the creator." And that's how "Greetings" came about.

Why did you end up going to the UK to record that track?

Phang had songs that he wanted to get licensed and released by Jet Star and Greensleeves. So we went with him over to the UK. While there we brought music on tapes and would just go to studios and record anywhere. Germany, France, England, America…we would record anywhere at the time.

What's also interesting about "Greetings" is that you started off as a singer, but "Greetings" showcases a slightly different vocal style from you. What motivated you to change up your approach a bit on "Greetings" as well as on some other tracks you've cut?

Music to me is very simple and basic. The chorus will tend to carry a more mid-range note where the fans can get the soul and feel of it. While the verse can sometimes be used like your reading poetry or sounding like your just flowing. When looking at other great songs that I heard over the years, I noticed that verses would often times be in this type of style while the chorus would bring the hook at really put the soul behind it. So "Greetings" to me was just like telling a story.

That's interesting because you also, as an artist, came to prominence during a crossroads for Jamaican music as it transitioned into the digital era.

Right. But even when I began to really take off as an artist, I wasn't really hooked onto that new, digital sound. Most of my songs since the '80s feature a live band. So when the "Sleng Teng" riddim came out, I didn't really get with it. It didn't give me much soul. I knew the original bass-line used on that and when played with the keyboard, it was too monotonous for me. I didn't really feel it.

During this time, soundsystems in the UK like Jah Shaka and Saxon Sound were coming to prominence. Since you were spending a lot of time in the UK during this time, can you speak at all to what you were hearing there and whether it influenced you or other Jamaican artists at the time?

Back in those days, I can remember reggae music was the "sound of the day" in London. And soundsystems like Saxon and Coxsone's would always play the roots music that was popular in the '60s. This was a lot like the original Jamaican soundsystems who would play dub and roots reggae. At the time, these UK soundsystems were still maintaining this type of quality music.

So when I was there and hearing them, I was still getting that original feel and sound from them despite being outside of Jamaica. Saxon and Coxsone were really keeping the originality of the music going. So because of this, I went around with the youths at the time from Saxon Sound and then Coxsone as well and Blacka Dread too. They were the real founders of the dancehall movement at the time in England.

Do you think they ended up influence Jamaican artists at all?

I would say that DJs like Tippa Irie, Daddy Colonel and Papa Levi were actually influenced by us because they started off listening to DJs from Jamaica like U-Roy, Big Youth, U-Brown, and Lone Ranger. All of them were popular in the late '60s and early '70s when the England DJs were attending dancehalls in the UK at the time and they were probably hearing these records being played.

I will say that Papa Levi struck me by surprise when he came with that song ("Mi God Mi King") where he was like speed talking over that same "Heavenless" riddim that I cut "Greetings" over.

Did that new vocal style influence you at all? You are a singer first but you've also added an element of improvisation to some of your songs over the years as we.

I was more feeling it from a musical and melody standpoint. What you are hearing nowadays, where reggae is concerned, seems to deal mainly with two different cards. You can sing melodically over it or your can sound almost like you are chanting. Even if you listen to some of Bob Marley's songs, some of the verses he almost just talking to you. It's not like the melody is carried throughout. The dancehall of today is often giving it to you in this straight way-- almost just straight talking. Back in the day, though, with people like Burning Spear or even like Jimmy Cliff, they were doing this to a certain extent too.

Reggae music overall comes from the soul in a way in which people express themselves. They don't try and refine it or sugar-coat it. They just express themselves but it's also still in the key of the music and still in the note. Some people will say that it doesn't sound like we really sing ballads but we've got that with our Ken Boothe's and John Holt or Alton Ellis who give you more melody and prettiness. But with Bob Marley and the Wailers and Burning Spear, they came at you sometimes with that more talking/chanting style. So in the '80s with Barrington Levy, you would also hear that same type of style incorporated into their songs.

Because of that, sometimes people come at me like I am a DJ but I am not. If I was a DJ I would be talking a lot more in my songs because it's easier to talk than sing so many words. [Laughs]

We're you cutting many dubplates with UK soundsystems?

Yes, Saxon got a lot of dubplates from me as well as Coxsone. Saxon used to come to Jamaica and cut dubplates before returning to England. And they would do it at Jammy's recording studio.

They would ask, and if we felt like it we would cut a dubplate with them. See, if they got a Half Pint or a Barrington Levy dubplate special that would give them something different they could play that would give the name of their soundsystem a promotion. So we would do it sometimes to give the dancehall a little more spunk like "this is the right sound! this is the big sound!" Now in Jamaica, after awhile, it goes as far as when they use the word "kill," it doesn't mean physically but more like "pull the plug on that sound" because this sound is the best sound.

When you were traveling around the UK hearing these soundsystems, how did they differ to the soundsystems in Jamaica?

To me, the soundsystems in the UK were more foundational. They were still maintaining that culture aspect of the sound. Locally, here in Kingston, we were evolving and experimenting with the technology and the rise of the digital sound. We even would sometimes merge whatever the latest sound was from Europe as well as England. Even with groups like Soul II Soul, the bass felt similar to what Robbie would play from Sly and Robbie. Or with Maxi Priest, it sounded pop but you could also hear the reggae influence in it. That Cat Stevens song he did, you could really hear it there. It made me feel good at the time that the English youths were still pursuing the reggae flavor at the time.

England is really known to be one of the countries that really establish reggae music from way back. And they still maintain it. Over the years, I've learned that even Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones would come to Jamaica and come to the partys and hear the records being played back in the late '60s. Just the other day I was watching Sting at the Grammy Awards, and did you know that he used to live here in the 1970s when he was in The Police? People like Paul Simon and Johnny Cash would come to Kingston too.

Right now, the Jamaican economy is really struggling. How does that effect the Jamaican music industry? Does that push you to travel abroad?

To make a living, going abroad is an option. My whole perspective on the music of Jamaica right now is that I want it to become more sentimental. Some people say, I am just a sentimental fool but I do believe that truth and goodwill will surpass all the negative energies and the cursing and bragging about how "I'm the one" or "I'm the this and that." That wasn't how I grew up with the music. There wasn't even much of a crave for money-making back then. Even Bob Marley said it. Back in the day, the way music came about was to bring us joy. To have some fun and to dance. It didn't have much to with the money-making part of it.

The business aspect really came into play when other people began to invest into the music and realized that it could provide earnings. That's where most of us had to get proper management from those who knew how to represent and who knew what was going on. There's a lot of earnings that can still come from the music internationally. But when you look at the charts 20 years ago, you would see an artist selling 1 or 2 million records. Music isn't really selling that much nowadays. It's more about downloading. And that downloading concept is interesting because it brings the music to that one person who loves a specific song and not just an entire record or everyone's records. To me, there's a sentimentality involved in that. Picking just the songs you like from an album and listening to those makes listening to music much more personal. And to me, that's the way music has always been, personal and appealing to a person who really loves the music.

On that note, do you still retain all the rights to your music? I know that many reggae artists, like Burning Spear, have had trouble regaining the rights to their music and getting proper royalties.

That's why its important to have proper management who knows what's going on and will properly represent. I have myself a management team as well as a lawyer who started working with me in about 1992 and he has done tremendous things so far by taking care of all the rights to all of music.

Even all your early singles?

Yeah, we got them all back. It's important too because I have a recent deal with Universal publishing that picks up from where my expired deal with BMG left off. And that's where it matters most, where your rights are really protected and reserved and can earn. That way even your great-grandchildren can become beneficiaries of it. [laughs]

You mentioned the importance of keeping positivity and goodwill in the music. When dancehall shifted more towards gun talk and slackness, you still stuck to those more conscious and positive themes. Was that difficult? We're you ever tempted to pick up the trends of the day?

There wasn't any type of temptation to be involved in this. I was totally against it and at times, I was a bit disturbed by it. However, I wasn't losing my mind over it because I know, throughout the world, people will come and people will go. People will say "yes" and people will say "nay." And people will talk clean and people will talk dirty. I know that there is a season for everything. And I feel that the best quality music, for even your children and my children, will be embraced more when they become more knowing of their roots and their past.

I think I still stayed on the right track, though. I am a person who has a mind that looks forward in a futuristic way but also in optimistic way that we can still have a better way of life or solution to come. And with my music, I want people to come to appreciate it or acknowledge or learn from what I was saying in a simple way, one that doesn't sound too arrogant or bitter.

Right now in Jamaica there is a live band movement that is very "conscious" and positive in nature. Do you think it is just a passing trend or something that is going to last?

I think that because we've grown so much and have so much access to different music that people will continue to acknowledge the live band. Take a group like Rootz Underground. When I hear them I get a feeling that is similar to what a band like Steel Pulse was about. Watching the TV here in Jamaica, I see some new bands coming together on the program 'Smile Jamaica' and I think it's a real rebirth here. Even if they don't take off like Bob Marley and the Wailers or other bands from Jamaica, I still think these bands and this new movement will have its place and time in Jamaican music as a whole. Jamaicans are musically inclined and when we hear a band, we're going to go in, give it a look and maybe start to dance.